Decolonizing the Steadies: from The Sovereignty of Mangoes to Tropics

past

04/24/2022 — 05/07/2022

Both parts of the project aimed to evidence the microhistories of the mango and the tropics, to portray them in their signifying ambiguity and as colonizing identity elements of the Venezuelan imaginaries. Destabilizing their founding persistence was a key to accessing other ways of understanding the histories that shape us as a nation, as a landscape, and as an identity.

Thousands of words, objects, and definitions populate our language and imaginary, many of which come from other languages and territories but have inevitably become ours. How can we trace them? How do we locate their entry and establishment as elements that identify a specific territory within the histories that shape us? In which part of society could a reflection on the knowledge around these now stable signifiers have an impact?

Opening history from the slightest, from the almost unnoticeable, intending to delve into some of the established signifiers of the Venezuelan metamemory, was the intention behind Esvin Alarcón Lam’s (Guatemala, 1988-) recent formative project. This LA ESCUELA___ Classroom was carried out in two parts: The Sovereignty of Mangoes, in Caracas, and Tropics, in Mérida, during April and May 2022, respectively.

The artist selected two basic items in the traditional and current Venezuelan identity patterns. One of them was the mango, a fruit that appears to belong to the warm zones of the country. The other was the word trópico (the tropics), a determining definition for countries like Venezuela, which are geographically located in the intertropical zone of the northern hemisphere, between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn.

Both parts of the project aimed to evidence the microhistories of the mango and the tropics, to portray them in their signifying ambiguity and as colonizing identity elements of the Venezuelan imaginaries. Destabilizing their founding persistence was a key to accessing other ways of understanding the histories that shape us as a nation, as a landscape, and as an identity. Conceived as collective actions with a pedagogical and didactic impact on the participants, they were carried out along with professors and students from public universities.

The Sovereignty of Mangoes

Mangoes, mangoes, and more mangoes stack certain areas of Venezuela between April and August each year. They are part of a stable identity in the national metamemory as part of our food culture; they are trees that grow spontaneously and seemingly without order.

The Venezuelan cultural narratives around mango are numerous: ranging from the question of whether Simón Bolívar the Liberator ate mangoes, to states like Cojedes, which has two monuments to the mango, a coat of arms that features the fruit, and a mango award for honorary citizens—due to the appreciation they have for the benefits that this crop brings to the state. There is also the economic dimension of its export trade or the political-nutritional relevance that this fruit has in the lives of ordinary citizens. However, the mango is not a native Venezuelan fruit.

The first mango seeds arrived in the country in 1798, brought by Fermín de Sancinenea in a ship of the Guipuzcoana Company. He planted them in Angostura— present-day Ciudad Bolívar—in the country’s southeast. From then on, the species found in Venezuela favorable soil for its growth and expansion, preferring the warmer climate regions. Its intense presence progressively and silently colonized the lands, to the point that today it is inconceivable to think of Venezuela without mangoes.

This fruitful tree has established its sovereignty in full autonomy, despite having been one more element of colonization. Esvin Alarcón Lam appropriates this narrative through an image found on the Internet: a photograph of a monument to the mango. The artist begins the appropriation process with this enigma and, thus, his operation as a historian, geographer, and educator. What could lead to the construction of such a monument? What was the relevance of the mango to deserve such a commemoration, and furthermore, its hyperbolized presence: a solitary mango?

The Sovereignty of Mangoes undertakes a reflection on the silent colonizations—namely, that of the foods that adapt to new territories, interweaving histories, needs, and steady identities. Time has positioned the perception that ‘it has always been here,’ without thinking about the narratives that precede it. This is precisely what operated in the devices built by the artist together with students and professors from the Universidad Central de Venezuela and the Universidad Simón Bolívar.

Acting as a historian, Alarcón Lam roamed the archives of memory and borrowed the lances that carried the banners, which today we know as the flagpoles that raise the flags that identify nations. These commemorative objects were initially weapons of war, from Ancient Greece to the rise and establishment of the Western world. Later, with colonization, they were extended as elements of global order and, with them, their objects of advancement and domination arrived in our territories.

The flagpoles of contemporary flags kept the metallic spearhead, which is generally ornamented and sharp-edged, as this was necessary for the melee. So, this device is a war weapon now transformed into an ornamental object, though it has not lost its primary meaning of close aggression towards the other.

The Sovereignty of Mangoes brings together these elements of colonization—the silent and the armed—to implement a collective action that decolonizes both. The mango is now understood as an offering of the land that adapts to the new and grows, thus creating self-standing sovereignty, an original, non-delegated, unlimited power. This sovereignty, together with the spearheads of the flagpoles, configured devices to collect mangoes from the trees that grow spontaneously throughout the city of Caracas.

By rethinking these two elements—mangoes and spearheads—and their signifiers, Alarcón Lam proposed a new vision of flags, which now would not belong to a nation or a defining identity but to the joy of a table that showed its crossings as a consequence of the processes of colonization. The flags were made with fruit-patterned plastic fabrics, the kind which is generally used for tablecloths on many Venezuelan tables nowadays. The fruit-collecting spearheads were designed and built by the students participating in the project.

A spontaneous conquest of the other, of another face of our history, in the midst of an act—as the artist himself states—"of tenderness, rebellion, which once installed, constitutes a soft and ephemeral monument that concentrates the collective work as a mobilizing power in itself, and which in addition, celebrates the irreverence of the mango trees that grow throughout the city." The action unfolded in the public spaces of Parque del Este in Caracas, where students, professors, and visitors took part in this hybrid offering.

Tropics

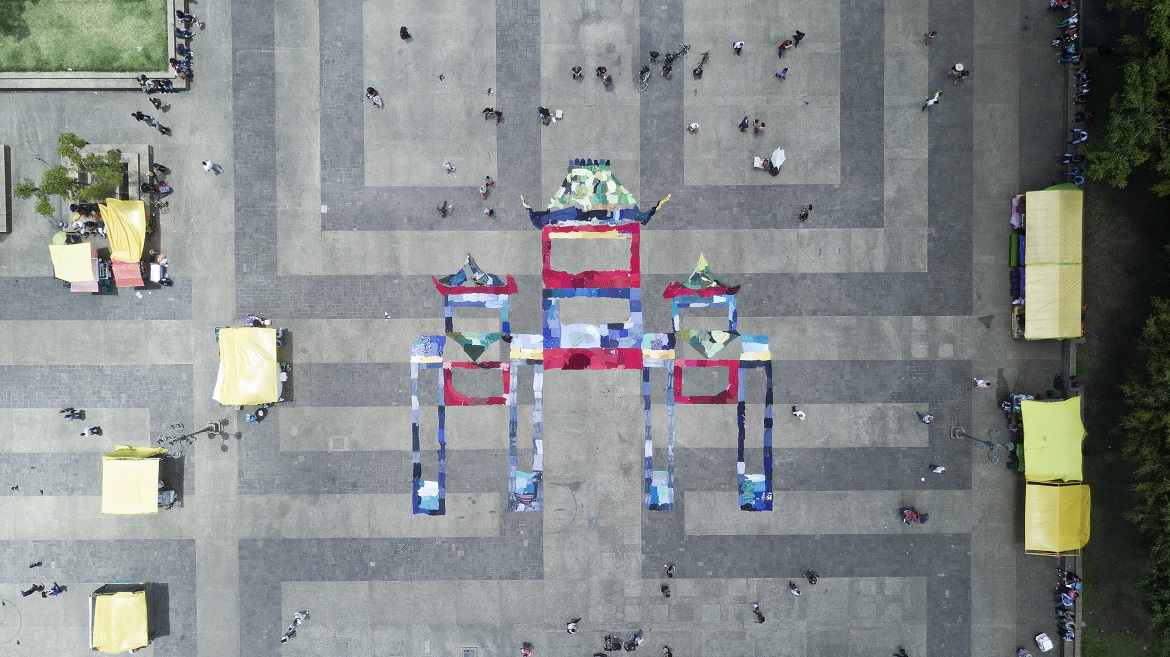

The insertion of Alarcón Lam into the Venezuelan landscape was in the city of Mérida, particularly in its university context, which was markedly different from The Sovereignty of Mangoes. Students from the Art History Department of the Faculty of Humanities and Education and from the Faculty of Arts of the Universidad de Los Andes participated in the artist’s proposal. He had conceived a portable brand lettering that would create a significant ambiguity. This was the driving idea behind the second part of the project. Alarcón Lam appropriated the letter signs that some cities have to highlight their names and their special ownership, but in this case, the sign did not identify the Mérida region—which has both moorlands and desert areas—but the tropics. Although, which tropics?

The established arguments about what we understand as the tropics have been configured not from geographical, climatological, or astronomical parameters but mainly from the visual and the sensory. The image that comes to mind when we hear the word 'tropics' is settled in our imaginary and mnemonic from the perspective of an Edenic paradise with beautiful coastlines and palm trees, bright colors, cheerful music, exotic places, and leisure or tourist entertainment, always located in warm and pleasant lands. Because of this single categorization, there is a hindrance to observing and knowing about the diverse biomes and climates that exist in the tropical zones, along with the geographical flattening and the unification of all the diversity contained in these regions.

Alarcón Lam appropriates this definition of the tropics solidified by history, mass media, and the popular trend of the city brands. This appropriation aimed to destabilize the notion of the tropics as we know and recognize them, to lead it into a different meaning, away from the one conferred by the images that have made it popular. In the artist's conception, the signifier word acts from its adjective function amid a rhetorical process that alters its content while subverting the landscape and the environment where the brand lettering would be placed: the moorlands of Mérida, far from any tropical sense, as they are intertropical mountainous ecosystems with cold climates, great biological richness, and vegetation characterized by frailejones (Espeletia schultzii).

Approaching the geography of the Mérida territory, its climatic diversity, and the biome of the Andean moorlands, evidenced the signifying flattening that the word enacts. Hence, the artist sought to create a visual ambiguity to decolonize the term. The word was analyzed by professors and students together with Alarcón Lam, from its etymology to its implementation as a single image, and how this has reverberated in the fields of art and imagery, as a sensitive event of consumption that cloaks diversity under historical, geographical, or mass media determinations that have characterized the tropics—also known as the Torrid Zone—from the beginning.

«The elders called it the Torrid Zone because the inhabitants of it had the Sun at its zenith and given that its rays were perpendicular to them, they judged that it would be mostly uninhabited because of its excessive heat. But the moderns have found cool, temperate, and healthy countries there, where one enjoys almost perpetual spring and fall, since the nights are almost 12 hours long and fresh winds pass over many leagues of sea during the day, tempering the rays of the Sun, causing frequent rains, and thus, in many parts of this area there are two fruit harvests each year and the trees always have flowers and fruit.»1.

The signifying, solid unity of the definition of the 'tropics' was deconstructed and reread in the collective action carried out in the Andean moorlands through the placement of the portable brand lettering, which was taken from Mérida city to the Sierra Nevada National Park to show its exultant tropical coloring amid a cold, earthy-colored landscape. With this action, Alarcón Lam inaugurated a third geographical space located in a reflexive narrative capable of generating a new discursive geography, intending to disturb the given and easily consumed perceptive spaces.

Placed on the site, the brand lettering activated the device that brings out spaces of otherness, of confrontation with the established, amid a new merging of opposites—both stated and assumed—in the Zone where the sun is always at its zenith. In this sense, Alarcón Lam's Tropics referred to an expanded and dismantling concept of the definition, a space of contrasting senses collectively produced through questioning the prevailing meaning with the aim of decolonizing it.

Decolonizing the Steadies

Esvin Alarcón Lam's project plays with the metamemory established in the imaginary of two fragments of Venezuela. With them, he opened a reflection on the given determinants found in identity discourses about who we are and about the community of uses of overlooked patrimonial signifiers. Time and history have placed them in a mnemonic sphere that makes them an indelible part of our contemporary daily lives, unaware of the circumstances surrounding their origin or their participation in the process of colonizing these lands.

In both The Sovereignty of Mangoes and Tropics, the artist borrowed overlooked signifiers, pieces of silent yet present microhistories, dismantling major signifiers in the processes of old and new colonizations, which crush and disfigure the otherness that makes up a nation.

On the one hand, there is the mango, a fruit that seems to be ours but has a history of food colonization, which now identifies a country that coexists with it and sees its expansion through the non-delegated, sovereign, and autonomous action of its spontaneous growth. The artist added the flagpoles that identified the territorial sovereignty, subverting the spearhead (a symbol of combat) by turning it into a basket for collecting the fruit’s sovereignty. An action that changed the established reading and decolonized colonization from microelements, turning them into an offering. A gesture of re-reading and awareness of the signifiers that shape us.

On the other hand, the use of the Tropics brand lettering altered the landscape of the Andean moorlands with its non-belonging to the system of meanings established for the word. The ambiguity created by the artist leads us to reflexively visualize the words that envision these lands as one steady geography under the discourse of Edenic countries, mainly provided by the mass media. With this action, the colonization of the diversity and alterity of the biomes, populations, and idiosyncrasies that exist in the tropics became visible.

The transit carried out by Esvin Alarcón Lam, from The Sovereignty of Mangoes to Tropics, encouraged the decolonization of two steady elements, dissecting them with participation from student communities in a joint reflection. Thus, the artist consolidated a third perceptive space where the microhistories emerged from a sort of dismantling consciousness around the signifiers that inadvertently configure us, unaware of the powers they represented in the configuration of the country.