Education from the Museum as a Resonant Strategy

02/01/2023

Are there pedagogical strategies that dislocate art museums from their vocation as civilizing devices to become institutions of reparation, rooted in their territories and histories?

Anthropocene, meta-crisis, ecological degradation; no matter the name, today we live in times of multiple, intertwined and profound crises. In a context of polarization, hopelessness and doubt, what role can art and education play? In the present journey I will reflect on the importance of both when seeking ways out of the neoliberal fatalism that Frederic Jameson captured so well with his phrase "it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism."

An invitation to a paradigm shift for exploring how educational practices and contemporary art can become tools for coexistence and repair in a world deeply damaged by fantasies of unlimited progress and the ruthless extraction of its resources.

Situating myself in the context of Chile, a country searching for new histories while going through a constitutional process led by its people, I will ask how collaborative learning relationships within museums can contribute to recomposing common frameworks for living together through kinship and imagination; and what art objects and practices—whether aestheticized artifacts or everyday practices and rituals—can contribute to that task. Are there pedagogical strategies that dislocate art museums from their vocation as civilizing devices to become institutions of reparation, rooted in their territories and histories? How might they actively engage in fighting/remediating the socio-economic inequality, environmental damage and lack of meaningful narratives that sparked the largest social revolt in recent Chilean history?

A Country in the Ruins of Capitalism

On October 18, 2019 something unusual happened in a large country at the far end of the global South: a public transport fare increase of 30 pesos (USD 0.03 approximately) unexpectedly mutated into a thunderous social outburst. It began in Santiago, the capital, and quickly spread throughout the country; within hours, hundreds of thousands of protesters poured into the streets, subway stations were set on fire, and the unmistakable noise of banging pots and pans rose as night fell.

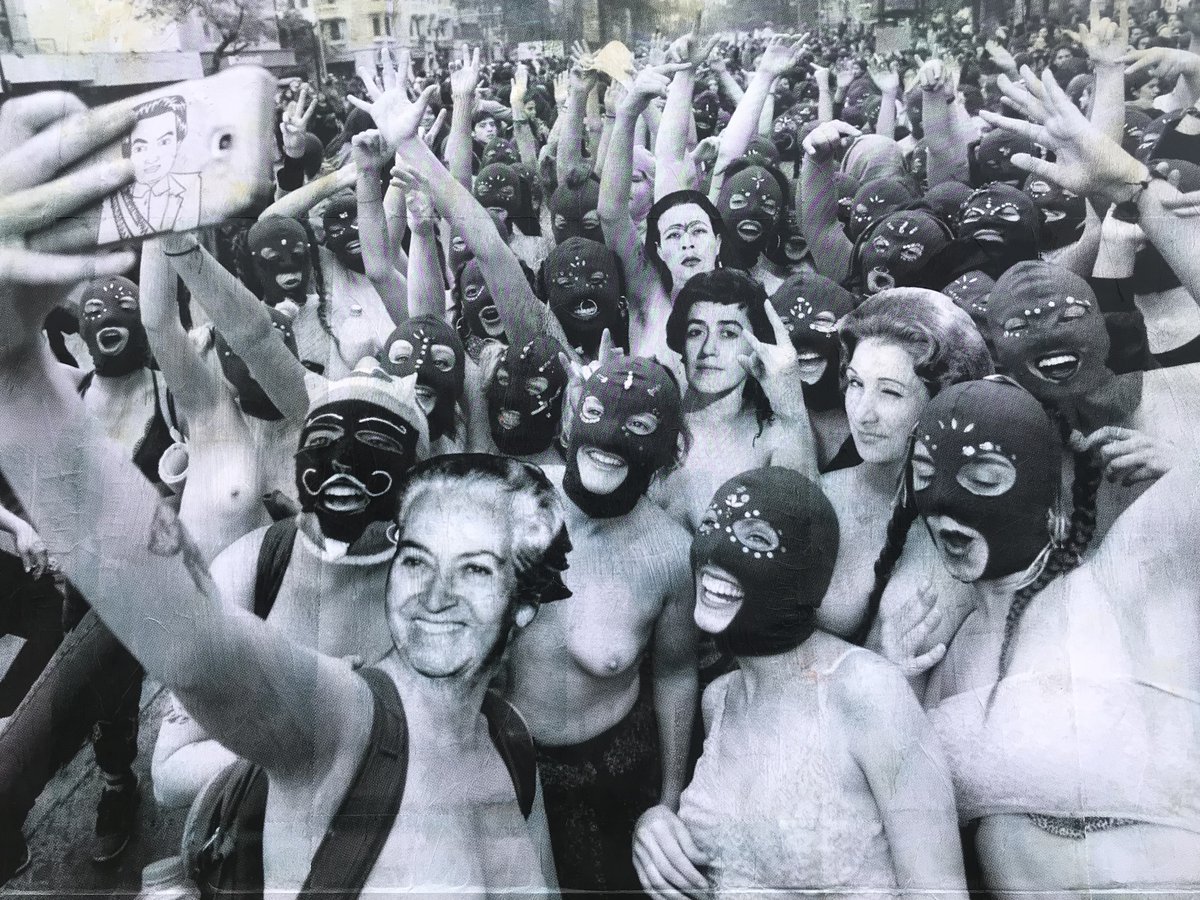

President Sebastián Piñera declared himself at war against a "powerful and implacable enemy," imposed curfews and sent the military into the streets, creating eerie parallels with the years of military dictatorship. But nothing was enough to stem the unstoppable flow of an unexpectedly broken dam. The country was paralyzed for months: classes were suspended, international forums (such as COP25 and APEC) were cancelled, and protesters constantly blocked roads. For weeks there were protests everywhere, at all hours, along with countless self-organized meetings of environmental activists, students, groups against the privatization of health care and pensions, unions, teachers, feminists. What had happened in Chile, a relatively peaceful country, widely regarded as an exception to Latin American instability?

As the demonstrators exclaimed, Chile had "awakened"—to what? The answer was tattooed on the skin of the street: "It's not 30 pesos, it's 30 years," they chanted, alluding to the 30 years of the constitution imposed by Augusto Pinochet's military dictatorship. Described as an "economic constitution," [1] it imposed one of the most intense neoliberal systems in the world. Pensions, the environment, health, education, and housing: the market, generating painful inequalities, colonized everything.

Just as the explosion was not "only" due to a rise in prices, neither was it "only" about the redistribution of capital. For neoliberalism affects not only access to economic goods and services (some of them fundamental), but also the way we make sense of the world, linking the ideal of a "good life" to endless work and endless optimization for consumption and progress. At the same time, the industrial and digital revolutions have eroded the relationship to our bodies and environments, and have affected our attention to and relationship with each other, the more-than-human [2] world and ourselves. In that sense, the Chilean outburst was not only an economic crisis, it was also a crisis of legitimacy and meaning that is not exclusive to Chile, but reflects and replicates global problems and challenges. Today there is a widespread feeling that we are in a moment of transition, in which some are bidding farewell to modernity [3] while others are already seeking to give birth to new possible worlds.[4]

On this point, the reflections of Anna Tsing (2015) are very enlightening, for whom we find ourselves today in the "ruins of capitalism": a precarious and unstable reality, devastated by the climate crisis driven by extreme extractivism and mercantilism. Inspired by the observation of matsutake mushrooms, which grow in territories ruined by wood monoculture, Tsing discovers new forms of life that emerge and even thrive in these disturbed environments.

Thus, the Chilean social explosion is merely another example of a ruinous ecological and social system, but one in which, as with the matsutake mushrooms, surprising ecologies emerge. If we look closely, it offers an alternative set of stories, desires and drives that challenge the monocultures of neoliberalism.

It is no wonder that an oft-repeated cry in the 2019 protests was that "another end of the world is possible." Following Foucault's ideas, where we find power, we find resistance, perhaps we can tap into a similar current; a glimmer of optimism in contrast to Jameson's despair, which the system takes advantage of to ground its symbolic power. The divine mandate of kings also once seemed inescapable; it is through radical acts of imagination and resistance that we can once again transform ourselves and break out of the trap of the unimaginable.

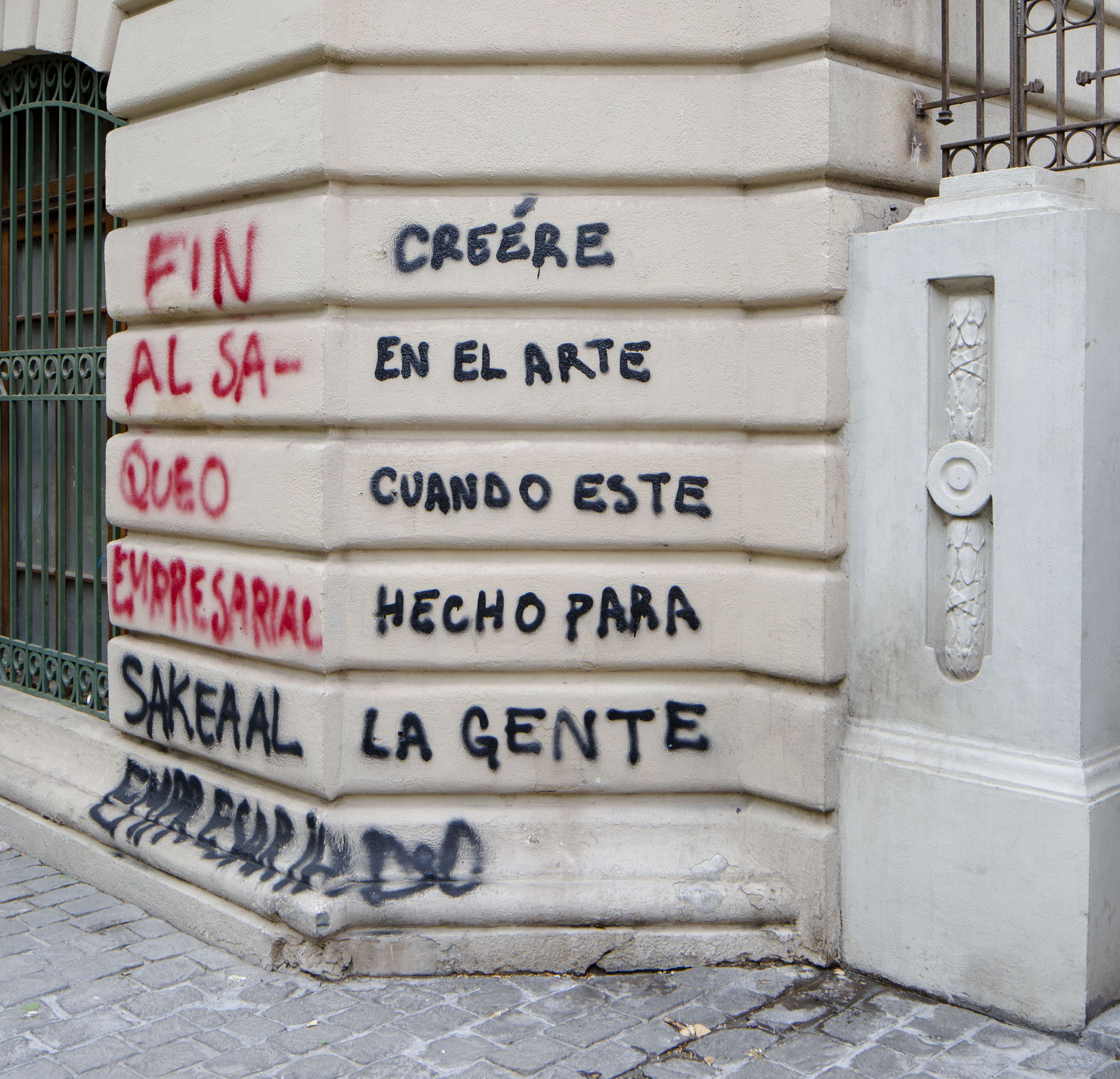

What is asked of museums in these circumstances? In the midst of chaos, hope and fear of such a spontaneous and leaderless popular movement, a graffiti on the wall of the National Museum of Fine Arts directly challenged them: "I will believe in art when it is made for the people." Museums were not exempt from the demands for a greater distribution of power and pluralism. It is certainly not the first time they have been criticized: in fact, they have received a good deal of criticism in recent decades, from decolonial scholars, feminists, anti-racists, queers and even ecologists. But in the last decade, the so-called 'educational turn' in curating has offered some hope for rooted and contextualized practices, which have sought to turn museums into allies and collaborators with their communities in order to think together not only about the challenges we face, but also about possible ways out and ways of escaping the neoliberal system.[5]

Art is precisely the space for sensitive and open encounters, capable of articulating alternatives for new futures and possibilities, built collectively between museums, their workers and visitors, creating the conditions for our society to reencounter a lost common world. Through small local and territorialized actions, and using contemporary art as an agent and tool, perhaps these institutions can thread new narratives for a changing world, trigger instances of radical imagination and create new localized knowledge ecologies.[6]

If we think of education within museums as a fruitful space for micropolitical action, these small educational communities could engage in actions that destabilize our obsession with novelty, progress, and optimization to focus on resonant strategies, rooted practices, and careful framing.

Education: From Bureaucracy to Laboratory, From the Private to the Commonplace

In 2008 curator Irit Rogoff coined a series of emerging practices that seemed to promise a more horizontal and transformative relationship between museums and communities as the 'educational turn.' Since then, projects centered on radical pedagogy, relational aesthetics, and community practices have become increasingly prevalent. Although those working in education departments have criticized this “turn,”[7] unexpectedly, many recognize that education in museums and galleries has the potential to offer individual agency and community transformation. If we believe that art can catalyze reflection and debate, it is precisely in the hands of education departments, the true zone of contact and friction in museums, that they appear. By creating complex, ambiguous and open zones of dissent and dialogue, education and mediation areas are able to think of new ways of existing in the world that go beyond modern ideals, while co-producing new collective knowledge.[8] Accepting instability and uncertain outcomes, as well as recognizing the importance of a polyphony of both audiences and museum staff, can redefine what a museum and its collection mean, involving those who bring their own knowledge and experiences outside the traditional canon, resulting in a truly emancipatory space.[9]

Art thus becomes a trap and an agent, capable of sensibilizing, moving and challenging. Anthropologist Néstor García Canclini refers to today's art as an ‘immanent art’: an object or action that plays with facts, with what could or could not happen, insinuating new meanings and signifiers.[10] Thus, in today's interdisciplinary and intercultural artworks we can find an opportunity to explore new knowledge that goes beyond the "hard" sciences, and that could generate new contextualized and localized understandings of contemporary society; as well as imagine and play with alternative worlds, becoming a tool of agency and resistance. Likewise, the idea of "art for the people" could be expanded to share how the idea of the "popular" in Latin America has been used both by hegemonic groups to differentiate themselves through the ideas of "high" and "low" culture, and by historically marginalized groups to reclaim and resignify rituals, traditions and everyday artistic expressions.

Finally, theories that focus on care, restoration, and conviviality are central to any educational and artistic project today.[11] Following Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick, it is perhaps time to disengage from the anesthetizing hermeneutics of suspicion to move from paranoid readings, which prefer to insist on misery and hopelessness, to restorative practices, which focus on nurturing and transformative changes.[12] Museums' mediation strategies in Chile could become an example of restorative practices in a context of ruins, moving from emergency, in which we face a chain of increasing crises, to urgency, understanding the problems, joining forces and moving forward.[13] In other words, moving from what we must oppose to what we want to imagine. Here, Illich's ideas about 'convivial tools'—that foster self-realization, responsibility and interdependence, in contrast to those that increase dependence and exploitation in today's modern society—can be fruitfully applied to pedagogical practices.[14]

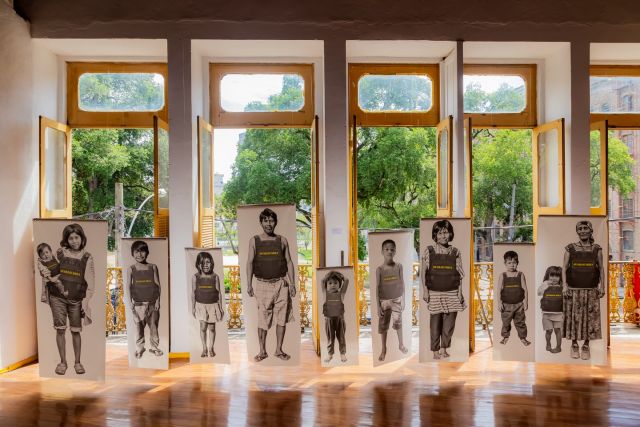

Some examples of this type of practices can be found in the way the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende team opted for the community's time -which requires long processes to generate trust, empathy and true collaboration- over those of the institution, thus privileging the creation of vegetable gardens and embroideries as privileged spaces to weave worlds in common.[15] Another example is the way in which the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo emphasizes the care of its constituents with HIV Awareness Days that mix rapid testing and dialogues around works from its collection related to that topic; also its projection of conversation and active listening with commitments such as the Podcast Irrupciones en el MAC. Finally, the Museo de Artes Visuales has been working for years with an extensive network of collaborating institutions, prioritizing associativity to generate more transversal and resonant activities.

Today we live in times of radical, horizontal and plural changes, before which, as a country, it is necessary to think of new ways of building community to coexist with the human and more-than-human. Education from art can contribute to this, generating community acts of imagination and deep hope [16] that choose to repair, care for, and co-construct a common world.

The need for reparative practices that go beyond identifying the poison to focus on conviviality, and localized, rooted, nurturing, emancipatory, and contextualized practice offer, perhaps, the best tool to seek ways out of the neoliberal labyrinth.