Artivisms for the Body, the Land, and Survival

09/22/2022

A selection of cases of artivism from Argentina, Chile, and Mexico, which work with practices of un-education and radical imagination, using tools that destabilize the prevailing order from the arts and various aesthetic devices [...] they lead to develop radical imaginations that are capable of changing the living conditions.

Thinking about the relationship between pedagogy and artistic practices is an urgent matter today, especially if we position ourselves in the possibility of understanding the capacity of current art for contributing to various contemporary social problems. As we will see, there are several artivists within the field of arts who are promoting possible alternatives to make visible the problems faced by different societies throughout our continent. Together, artists and activists are connecting systems of unlearning (radical pedagogies) for communities that are politically and socially empowered. These artists present other ways of understanding art, from a deep desire to contribute to the struggles for autonomy and justice of communities stripped of their survival conditions. From their practices, they are unpacking, revealing, and deconstructing the hierarchies that have characterized the field of art, enveloping it in a procedure that conveys transformative and emancipatory meanings through collectivization and unlearning as the pivot for it.

We will situate ourselves in this position to review emancipatory relationships between artivists, radical pedagogies, and social movements in contexts where capitalism has created subjugating conditions for numerous communities for causes ranging from violence in all its phases to the advance of conservatism and voracious neoliberalism in our region.

Thus, I will present a selection of cases of artivism from Argentina, Chile, and Mexico, which work with practices of un-education and radical imagination, by means of tools that destabilize the prevailing order from the arts and various aesthetic devices. These artists articulate themselves from the common (between artivists and communities) to offer mechanisms of transformation and emancipation. They work with the notion of participation (derived from hierarchical institutionalism, destroying that condition) that entails going beyond the field of art and towards the political. Therefore, they lead to develop radical imaginations that are capable of changing the living conditions of the inhabitants/participants/activists, through self-education, developing autonomy, and tactical and political collectivity through aesthetics.

Mexico: Challenging the Biostructures

Three collectives that bring together artists, intellectuals, theater people, and communities are challenging the biostructures that subjugate different communities in Mexico by promoting different ways of understanding reality. Lxs de Abajo is a community art group founded by Sara Pinedo and Cuauhtémoc Vásquez, playwrights and theater artists who work with children and teenagers from the town of San Juan de Abajo, in the state of León-Guanajuato. Lxs de Abajo is known for gathering numerous performers and creatives who offer their skills to the service of the group in order to address various tactics of radical imagination from different artistic disciplines (theater, urban art, political art).1 In their practice of un-education, through assemblies and workshops, they reconfigure the symbolic limitations to which they are subjected by their condition of extreme poverty.

Through self-knowledge, questioning and self-representation, they configure alternative narratives that allow them to imagine possible futures. Commonly in this population, when they grow up, they can only become construction workers, maquila laborers, or peasants. In Quinces [Fifteen] (2019), they presented a baseball game where they questioned the various stages of the coming of age through the popular celebration of the 15th birthday. They put on the table issues concerning motherhood, sexuality and genders, discussed possibilities for becoming autonomous beings, and prospects of inserting themselves (or not) into the labor sphere predisposed by society. Another case was Cómo llegar a Fuenteovejuna [How to Get to Fuenteovejuna] (2018), a play written together with the Chilean playwright Cristian Aravena. It was set in a street theater stage with the purpose of representing a scene where girls and teenagers subjected the public to questions about the conditions of women in a society where their bodies are placed at the service of the heteropatriarchal ruling and receive countless forms of violence, both internal and external.

Colectivo La Lleca is a group of performers and educators led by Lorena Méndez and Fernando Fuentes who have been dismantling the masculine and heteropatriarchal construction of prisoners at the Centro de Readaptación Social Varonil de Santa Martha Acatitla [Center for Male Social Rehabilitation of Santa Martha Acatitla] since 2004.2 Their works and actions move away from the status of art and into the therapeutic realm, where they directly affect the subalternate realities of men of different ages who are deprived of liberty. This casework aims to elaborate diverse strategies that circumvent government control to overcome barriers of space and body, affection, and non-formal education, leading to the dismantling of the violent male subject and moving towards one capable of restitution through compassion, empathy, and the destruction of the male mandate, so deeply rooted in them. Among their actions are Matrimonio colectivo [Collective Marriage] (2005), consisting of the union between Lorena Méndez, a group of inmates, and other mates with whom La Lleca works. It was intended as a way of compensating for the loss of affection, love and family due to their imprisonment, expanding those feelings into other directions.

According to Fernando Fuentes, this action sought to "break with heteronormativity to some extent, although the main point was to shake the notions of marriage and monogamy."3 Another case was Secretos de Martha [Martha’s Secrets] (2006), which explored the imagery of delinquency as a space for recognition, to highlight by contrast the resources that question the framework of visibility of criminals, to be able to take charge of the desires and life imageries of the convicts.

Alongside this, we have Mujeres en espiral, a group that since 2008 has become a bridge for the university sphere, female professors, students, artists, activists and intellectuals, to work with inmates of the Centro Federal de Readaptación Social Femenino de Santa Martha Acatitla [Federal Center for Female Social Rehabilitation of Santa Martha Acatitla], with the purpose of generating autonomy for women subjected to Mexico’s heteropatriarchal legal system. They have devised multiple actions (murals, books, fanzines, documentaries, short films) that portray the life of women in prison, especially foregrounding the failures and shortcomings in their judicial processes. They have formed a civil organization called Arte, Justicia y Género A.C., which fights for the rights of women deprived of liberty, based on the articulation of artistic, pedagogical, and legal practices from the perspective of gender and human rights. Among their productions, it is worth highlighting the audiovisual project Cihuatlán, Antígonas de Santa Martha (2017), which re-signified the figure of Antigone as a metaphor for the confinement of women and the political power that can emerge from there. This short film presents several cases where the authorities have violated the rights of women and the violent situations they have lived outside prison. As the collective puts it: "Like Antigone, they unearth themselves, speak out, and rebel against a system that constantly turns its back on them.”4

Argentina: Protests for the Land and Dignity

On our way south, we find Etcétera in Argentina, a group that stands out for being an interdisciplinary collective of artivists who have been involved in social struggles (violation of human rights, crisis and political representation, hunger, poverty) from 1998 until today,5 provoking actions of agitation, justice and denunciation; also breaking with the idea of "art for art's sake." By teaming up with H.I.J.O.S.,6 they produced escraches7 that denounced dozens of military repressors of the last Argentinean dictatorship. Their actions in support of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, for instance, and various organized territories that fight for public policies that benefit their communities are characteristic. Also remarkable is the engagement they generate with local agents, producing agencies from an aesthetic perspective that allow conveying and calling attention to problems that have been sustained in different moments of recent Argentinean history.

Such is the case of Explotar! [Explode!] (2000), a performance in which a caravan of characters loaded boxes fixed with dynamite containing a manifesto that denounced labor laws; El Mierdazo [The Shittery] (2002), which implied a collective call to throw excrement at the National Congress as a result of the 2001 economic crisis; or Contrabajos (or sin-fonía) (2004), a performance carried out on December 20 by actors, artists, and musicians who marched from the National Congress to the Plaza de Mayo, narrating the story of a "corporate stomach under the yoke of the boss and his condescending secretary,"8 which is rescued by workers and unemployed people with the help of the ‘H@mbre’9 (man-hunger). Together, they produced "the noise of their stomachs" (hunger) as a result of the serious labor crisis that the country was going through. Their actions arise and unfold from exchange and reciprocity between politically-organized communities and their management as visual "facilitators" of consciousness and emancipation.

Pao Lunch is a queer transfeminist artivist who is shattering gender structures through self-education and the politics of sharing, as well as the logics of artistic production, authorship, and naming (or recognition of authorship or the status of the artist). They generate diverse critical actions and works in solidarity with countless struggles of the sex-dissident communities, such as Contagiamos imágenes, Proyectorazo, and Piquete.10 Pao is constituted as such, substantially by "the places they inhabit,"11 political spaces destined to combat the place of the hegemonic common, unleashing meanings that question the condition of normality and the norm. This is why it is very important to recognize their work beyond the artistic sphere; that is, in the political field, bordering on illegality.

They are characterized by a self-convened collective work among peers who question the laws because these "are not made for all"; they also question the dominant structures of sex-gender identity, through teaching, art and activism. On the other hand, Pao works not only from this trench but also in solidarity with different regions that are uprising against oil extractivism. They intervene in conflict zones, bringing forth questions and images that challenge the economic statutes that allow the loss of the ecosystemic balance of nature and local populations. Also, together with their community of non-binary creatives, they offer several aesthetic tools to show solidarity with other struggles taking place inside and outside their country. The disobedient attitude that frames them within the artistic field stands out by dismantling the notions of uniqueness, originality, authorship, representative power, and symbolic exchange.

Outside the visual-aesthetic field, the work of the poet and artivist Dani Zelko stands out. He is disputing the hierarchy of the epistemological field by working with cross-border communities.12 He confronts different cases of displacement, territorial occupation and police repression in communities that have been forced to migrate or to self-convene, to rise up and fight the occupation and violence of the Global South. Based on work with testimonies, he invites all kinds of people to share their life experiences collectively or individually, in a narrative shaped from anonymity. The encounter between Dani and the communities opens a space-time "in which people can tell their life experiences." It is a "moment of self-knowledge," sensitive and contrary to the perception of productivity, where space is made to break the hegemonic narrative "and to be able to elaborate and reflect on things they are going through" in their own voices. Dani compiles these spoken memories in a notebook, which adds up several experiences and ends up becoming a kind of "book" format that enables the circulation of life memories. The process that goes from the moment of transcribing the spoken account to digitizing the notes for printing, hand-bound, and distributed among the communities is carried out at once. The transition does not have as a condition the dissemination of the memories as a catalog or an archive, since it lacks any editorial or market norm and logic. Rather, Dani and the communities share their memoirs with each other—which recount painful episodes that are moving and mobilizing at the same time—and then they share the “books” among themselves, resulting in a myriad of translations, copies, and modes of circulation.

The moment of writing, thus, is "a moment of listening and expanding knowledge," which aims "to think about what is going on, to think about how power is working, how to create resistance, how to carry out processes of struggle and mourning, and how the book can carry forward those struggles, demands or concrete ways of intervening in real conflicts."13 Thus, the book is thought of as a substrate for political tools aimed at action.

Chile: Political Disputes over Autonomy and Identity

Meanwhile in Chile, Dé_Tour [etnografía y derivas] by artist Jocelyn Muñoz stands out for raising various actions ranging from workshops, meeting spaces, and drifts with various local communities across their lands, located in the Fifth Region of Chile.14 The project’s leitmotiv is unlearning aimed at deconstructing—in her words—"the normative cultural matrix." Etno-Detour is an exploratory, collective, artivist and situated practice of territorial recognition that encourages critically rethinking sacrifice zones: areas that have been corrupted by capitalist extractivism and its effects on impoverished localities. With her practice, Muñoz has developed projects that connect art, pedagogy, and visual culture as a way of acknowledging the memories, stories and narratives that have been installed in the social imaginary. She also promotes many autonomous spaces marked by the intention of rethinking our productivist contemporaneity from the perspective of anti-capitalism and libertarian thought and practice.

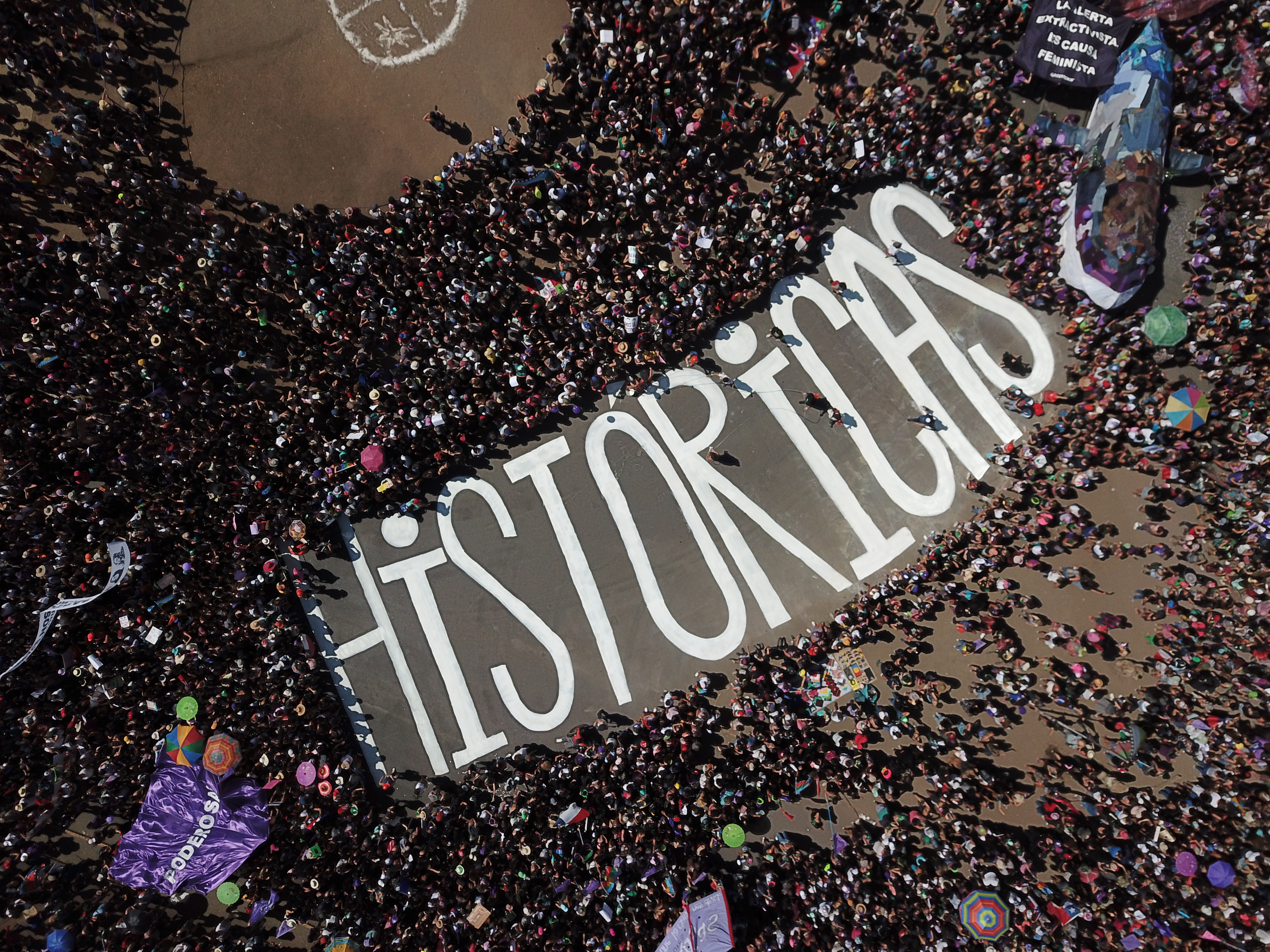

Brigada Laura Rodig is a feminist collective working at the crossings of politics, art, self-education, and symbolic dispute against the patriarchal order. They propose a series of aesthetic actions that overcome the binary establishment through feminist, countercultural, street and urban actions. As part of the Coordinadora Feminista 8M, they become active for propaganda and agitation purposes.15 In 2019 and 2021, they produced two actions aimed at renaming the stations of the Santiago Metro. The intention was to recode the places that have been named from the hegemonic point of view. In 2019, they sought to inscribe names of relevant women in the arts, sciences, politics and economics, which have been silenced by the dominant repertoire of the male ruling. In 2021, they renamed the stations to incorporate the demands of the local and regional feminist movement, displaying phrases such as "Feminist Constitution," "Don't let them narrow your streets," "Plurinational System of Care," "No more political sexual violence," "Union freedom," "No more lesbo hate," "Free and legal abortion," among others. In addition, they stand out for their multiple actions that range from pasting graphics, spray-paintings, textile confections, and stickers (from 2019 to 2021) with protest images and slogans on monuments, streets, walls, and public institutions to activate, propagate and spread the feminist militancy, and thus seize the fences that power establishes. Through assemblies and by influencing public and private spaces, they create collaborative instances for the self-management of care, rage and critical self-education, intending to incite a society that is anti-prison, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-discriminatory of sexual diversity.16

Lastly, the artivist Lucas Núñez addresses the dominant notions of gender and the stigmatization of the queer and LGBTI population living with HIV; he generates crossings between sexual-dissident creation and collective self-education. In Maleza en el jardín [Weeds in the Garden] (2018), he shapes a landscape that attempts to recode the imposed imageries of the HIV-positive population. Together with Anathole Schall (botanical biologist), he created an installation that used "despised" wild plants as a metaphor of the place relegated to the outcasts of heteronormativity within society. With it, he meant to shake the established masculine standards and foreground identities that are made invisible by the State, while vindicating a history of sexual dissidence and of the people who died from diseases caused by AIDS in Chile. He solves this reinscription by assuming the place of the art institution as a school, producing workshops out of the hidden stories of his community with diverse agents who are part of it and activating these places with mediators who campaign every day in favor of replicating forms of affectivity and sexuality using Núñez's visual propositions. He also uses his work to influence educational institutions and insert sexual education content into the classroom. Other works of his are El Estado no nos protege [The State Does Not Protect Us] (2019) and Cuántos frascos se necesitan para conseguir una cura [How Many Bottles Are Needed to Find a Cure] (2020). Both collective actions were installed into the social imaginary by occupying the street as a space for the re-inscription of AIDS, stimulating a reflection on its pandemic condition to generate a visual impact that leads to looking against the grain of public policies on sexuality and sexually transmitted diseases.

I present this map of experiences as a non-exclusive and non-excluding compass of agglutinated forces developed by diverse cultural agents—not only artists but activists, educators, and community speakers too— who have carried out different forms of collaborative work, from feeling, thinking, and experimenting with specific communities, common alternatives to the violence of biopolitics, capitalism, human rights violations, heteropatriarchy, migration, and poverty in its broadest sense.