Collective Creation as a Form of Promiscuous Care

12/11/2022

Promiscuity implies indiscriminate care, going beyond the idea of only taking care of "our own" [...] We will trace care practices through specific art interventions by the collectives Mujeres Creando (Bolivia), Delight Lab (Chile), and Etcetera (Argentina).

From the moment of birth until the moment of death, we are required to perform care. It represents an essential aspect of the sustainability of life, specifically for the reproduction of social and ecological systems. However, these care tasks have been overlooked and excluded by patriarchal, colonial, and capitalist systems themselves due to the invisibility of both their subjects and the concepts of interrelation and interdependence that characterize our relationship with the world. In a separate, dissociated evolution, they have evolved in two distant modes: the "private" and the "collective," to the point that they are considered opposites: private health care or public health care, private education or public education, etc. In this context, we'll examine care both as a powerful concept and as a political practice of re-existence that can be strategically applied in the face of dispossession and in defense of life as well, understanding ‘life’ as all the animate and inanimate systems and networks that sustain it.[1]

We will trace care practices through specific art interventions by the collectives Mujeres Creando (Bolivia), Delight Lab (Chile), and Etcetera (Argentina).

In the year 2020, the Care Collective published The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence, in which they coined the term ‘promiscuous care.’ [2] The term is derived from what gay activists and leaders wrote and elaborated upon during the 1980s and 1990s AIDS pandemic, such as Douglas Crimp's essay "How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic" which argues that promiscuity would save the gay community instead of destroying it. Due to promiscuity, they would seek other forms of safe intimacy beyond penetration, intimacy based on care. Moreover, promiscuity implies indiscriminate care, going beyond the idea of only taking care of "our own." If the State allocates enough resources to care for the needy, people would feel secure enough to not only care for themselves but also for others as well.

A promiscuous care approach looks beyond kinship patterns to encompass broader forms of care in all spheres of social life, not only in our families, but also in our communities, markets, states, and transnational relationships with humans and non-humans.

The manifesto emphasizes the importance of care as a driving force in both the economy as well as the State. According to them, a supportive government should take care of the collective joy of all its citizens rather than focusing solely on individual desires, proving the importance of what might be called "collective desires," which have generally been regarded negatively. To build a more convivial city, the collective advocates the reclamation of public spaces as a way to create caring places. It sets out an agenda for the environment, the most urgent of all, placing care at the center of our relationship with the natural world. In the face of the ecological dilemma, where individual solutions are merely a way of alleviating guilt, maybe they will be used to demonstrate the need for thinking collectively. Now, if we apply this theory to collective creative work as a means of reproducing and amplifying promiscuous care, how would that play out? How can we use artistic practice as a platform to teach and learn new social relations?

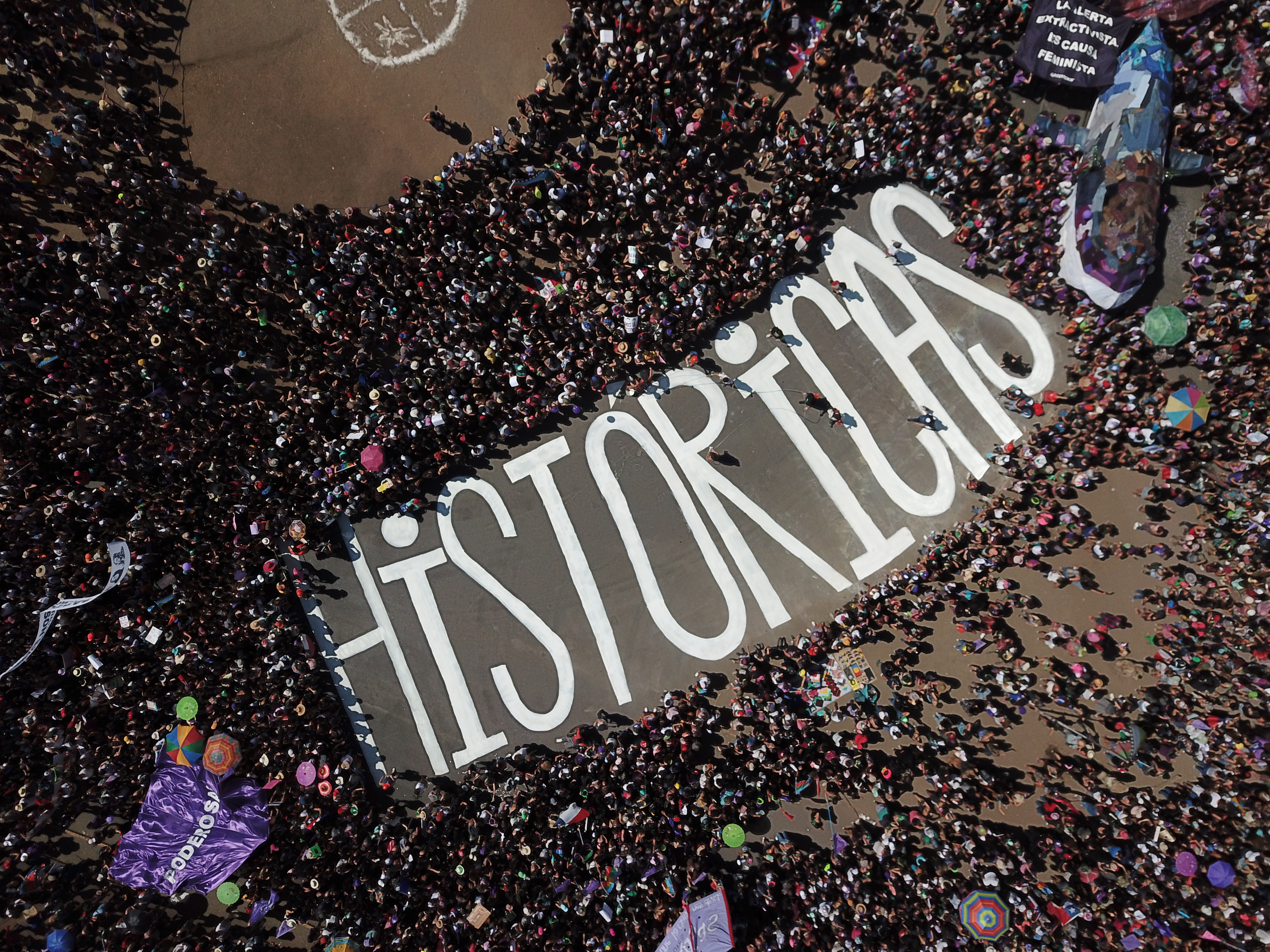

For instance, the work of Mujeres Creando has been anchored in neighborhood and community dynamics, especially in La Paz's urban context, although their interests and actions have also spanned rural communities and areas. Incentives came from the right to speak with their own voice and to manage their own image, still suppressed by neoliberalism, internal colonialism, recycled patriarchy, and hegemonic feminism. The idea of creating a community manifested itself in a house in the Delicias neighborhood, where women from different backgrounds were living together: city and country women, mestizas, Aymaras, Quechuas, university students, housewives, single mothers, lesbians, etc. Together, they created the Grandmother's Pantry, which provided natural food for the neighborhood; the Panal de las Abejitas library and pedagogical space for boys and girls; [3] as well as health and literacy workshops for a group of students from Achacachi. As a result, a series of aesthetic-political movements based on horizontality emerged.

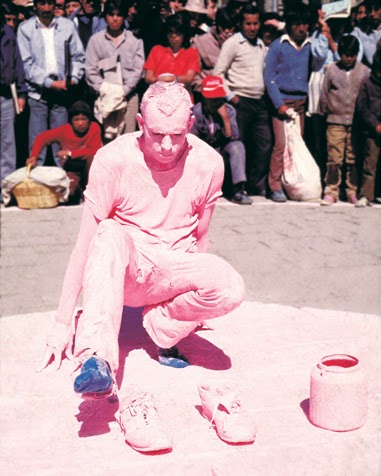

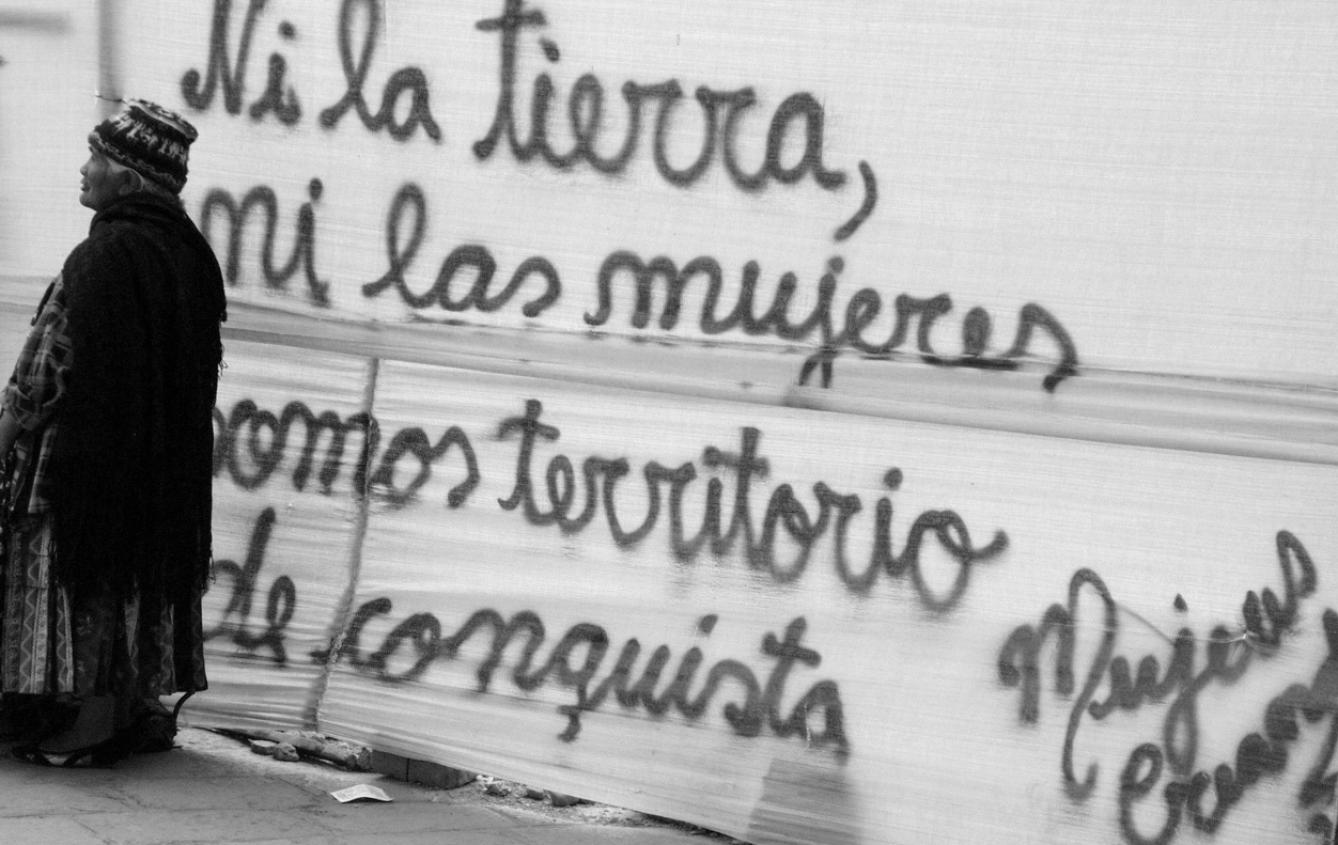

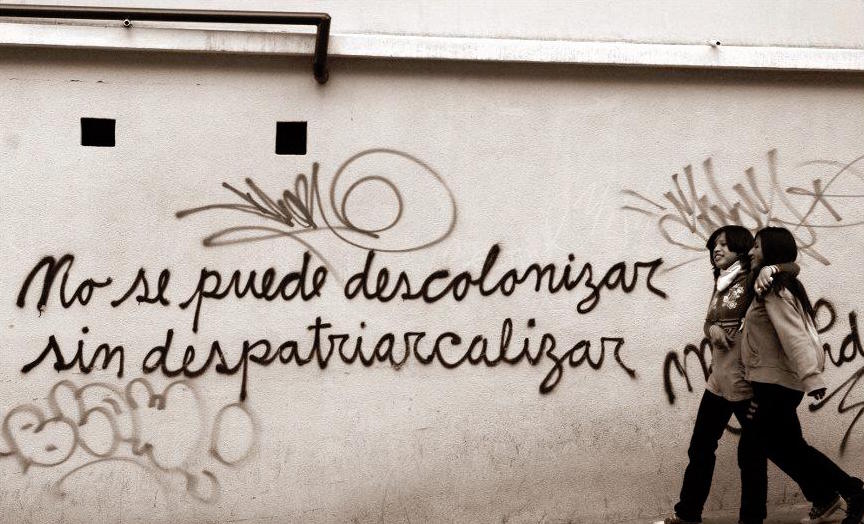

Through their graffiti, publications, and performances, Mujeres Creando demonstrate creativity and political imagination from collectiveness as a key tool for deneoliberalizing, decolonizing, and depatriarchalizing the imaginary production apparatus that has historically subjugated them. They merge the need to survive the singular, the own (as long as it is not property), into a form of collective creation through graffiti writings that are collectively signed. A few examples of such phrases are: Para ella la culpa, para él la disculpa [For her the blame, for him the apology]; Ni la tierra ni las mujeres somos territorio de conquista [Neither the earth nor women are territories of conquest]; No vengo de tu costilla, vienes de mi entrepierna [I don't come from your rib, you come from my crotch]. The display and creation of these works weaves a network of care that is at the center of all of their processes. As a community, networks are established to benefit the whole and to serve the common good. Through art and activism, they penetrate the social fabric and disarm a whole machinery of visual senses. Through performance and graffiti, “they continue to settle in the hearts of the unsuspecting, calling for disobedience, pleasure, love, and struggle to be part of our daily lives.” [4]

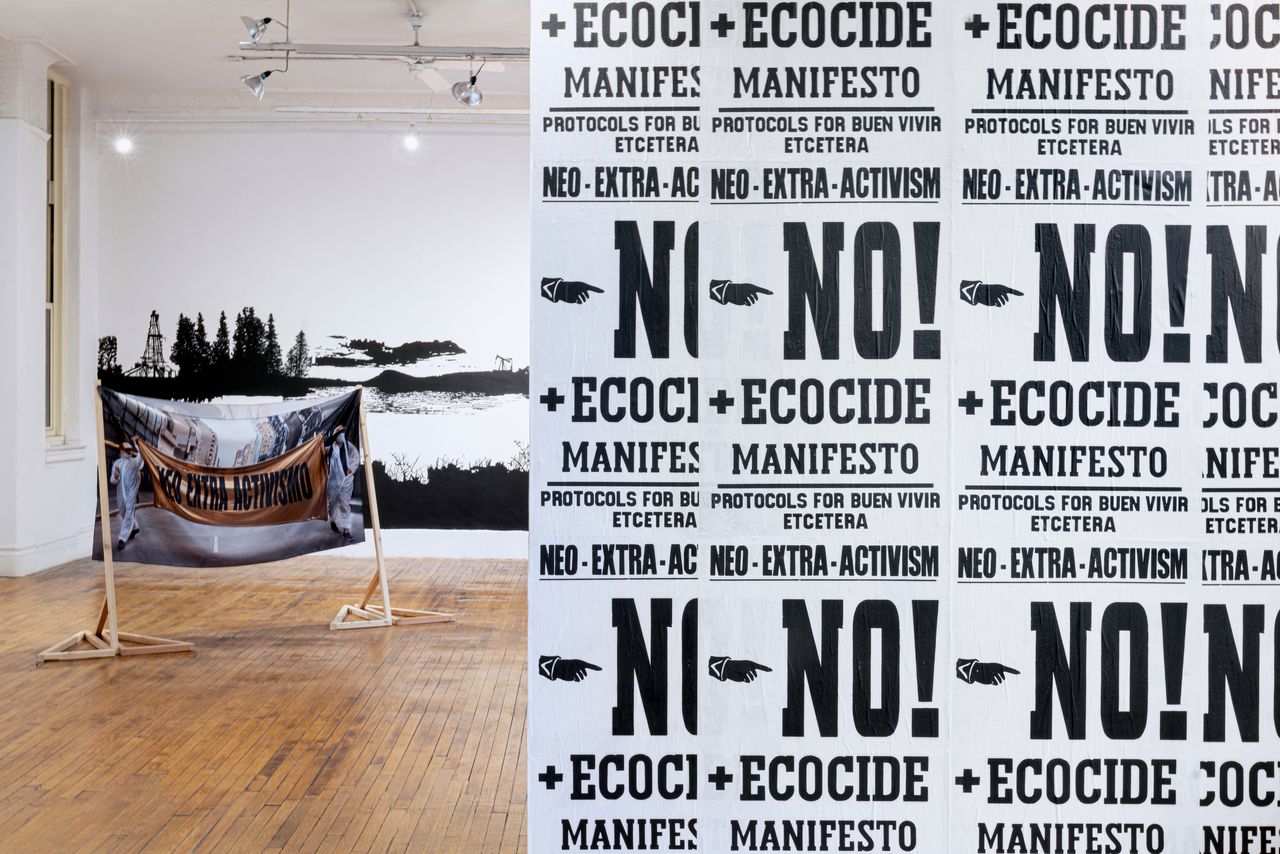

From a different platform and approach, we find the Etcetera collective. It is a project that connects artists and activists from Latin America and New York, establishing networks of communication between international artists, activists, and local communities through their investigation into state and corporate responsibility for environmental crimes and violations of human rights. With a focus on the indigenous notion of ‘buen vivir’ (sumak kawsay, meaning ‘good living’), their latest exhibition at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural & Educational Center, NEO-EXTRA-ACTIVISM Protocols for Buen Vivir (May 20–June 17, 2022, New York City), explored the idea of living well through community, which extends to the production of art, culture, and knowledge by non-extractivist means. In this exhibition, the collective served as a space for meeting, sharing, and organizing around urgent topics in an effort to foster a sense of community. The public was invited to reflect on the question “What does ‘Buen Vivir’ look like in an urban setting?” Blurring the idea of territorial boundaries, they work to find alliances and shared imaginaries that transcend colonial borders.

Both groups challenge Western aesthetics, as they have nothing to do with the idea from which “embellishment” is generally conceived. From different trajectories and aesthetics, they are united in challenging hegemonic power patterns, promoting buen vivir as a worldview, as a way of living that emphasizes joy, pleasure, justice, and solidarity. It is in their work that they develop a disassociation from canonical structures, from their artistic genealogy, and from their creative devices to immerse themselves into the world of the sensitive, the non-human, and, most importantly, the collectivization of knowledge, where the concrete realization is that of an individual—"the artist"—but it is a representation of the common.

As another example of collective activism, the siblings Andrea and Octavio Gana make up the Delight Lab collective, which uses the video mapping technique in their interventions. Their projections went viral on social media during the intense riots and social mobilizations in Chile in October of 2019, when they carried out light interventions in nerve centers such as Plaza Baquedano or the Telefónica Tower in Santiago. Collectively, the public space served as a platform for containment, grouping, and launching during the massive social explosion. There was a popular slogan back then: “It's not 30 pesos, it's thirty years,” in reference to the fact that the immediate cause of the awakening was the rise in the rate of the Santiago public transport system that came into effect on October 6, 2019. Santiago's metro was overrun with students evading fares. Later, a series of massive demonstrations and serious riots broke out all over Chile, taking the neoliberal city as the scene of the revolt.

In this context, Delight Lab projected phrases such as No estamos en guerra, estamos unidos [We are not at war, we are united], ¿Qué entiende Ud. por democracia? [What do you understand by democracy?], Chile despertó [Chile woke up], and Por un nuevo país [Toward a new country] on the Telefónica Tower, a few blocks from Plaza Baquedano—renamed by the people as Plaza de la Dignidad. During the "Chilean awakening" and in response to the military and police brutality, the collective projected seven slogans over the seven nights that the curfew lasted. These powerful messages were projected onto the city in a poetics that combined monumentality with evanescence. A poetics that warns that contemporary arts are not defined by predetermined modes and rhetoric but rather by a multiplicity of resources.

Ultimately, this gesture consists of a rewriting of the city in terms of a political revolution, and it was done in service of a process of collective healing and catharsis. In the modern world, the disease becomes singular suffering, but the disease is nothing more than an affected body in an environment that affects it; to heal means to reinstall the common in a body that has been singled out by disease, separated from the collectiveness to heal by itself. However, the wound is caused, partly, by institutional oppression and experiences of loss that reside collectively and are rooted in the unconscious. [5] Through the use of both massive formats of advertising and design, as well as social movement rhetorics, Delight Lab utilized the public space of struggle with a slogan that represented collective discomfort.

There is no doubt that typography performs an important role in the three collectives, since it is capable of transforming verbal ideas into visual images, thus enhancing the readability and strength of the message, as well as making it more appealing to the audience.

By combining phonetic proximity, semantic articulation, and visual image in a manner that ensures a blend of all three, a device is created. Regaining recognition through the power of visuality will always be a political act.

The incorporation of collectiveness into the creative act and shared experience establishes care as a respectable concept for everyone involved. Essentially, providing care that is promiscuous, occurs not only in intimate relationships, but also in the environments we inhabit and move around in, thus fostering mutual support in public spaces. Reinforces a sense of security, thereby facilitating a greater level of care and engagement among the entire community. There is also a very strong influence of indigenous kinship, which recognizes and respects the relationship between all living things, including the environment, as a way of coexisting, decolonizing the idea of care. Throughout Latin America, the Andean worldview still permeates daily practices and complicates the notion of care by emphasizing an integrated relationship with nature, understood as a vital space that cannot be separated from society. Thus, the idea of interdependence and human care also extends to the care of the "common goods" of nature.

Our discussion of collectives in this article is just one example of how decolonial visuality can be replaced as a center of artistic and cultural practices. Both confronting the neo-extractivist system presented as the panacea for development and modernization in the countries of the South and claiming and achieving human and citizenship rights.