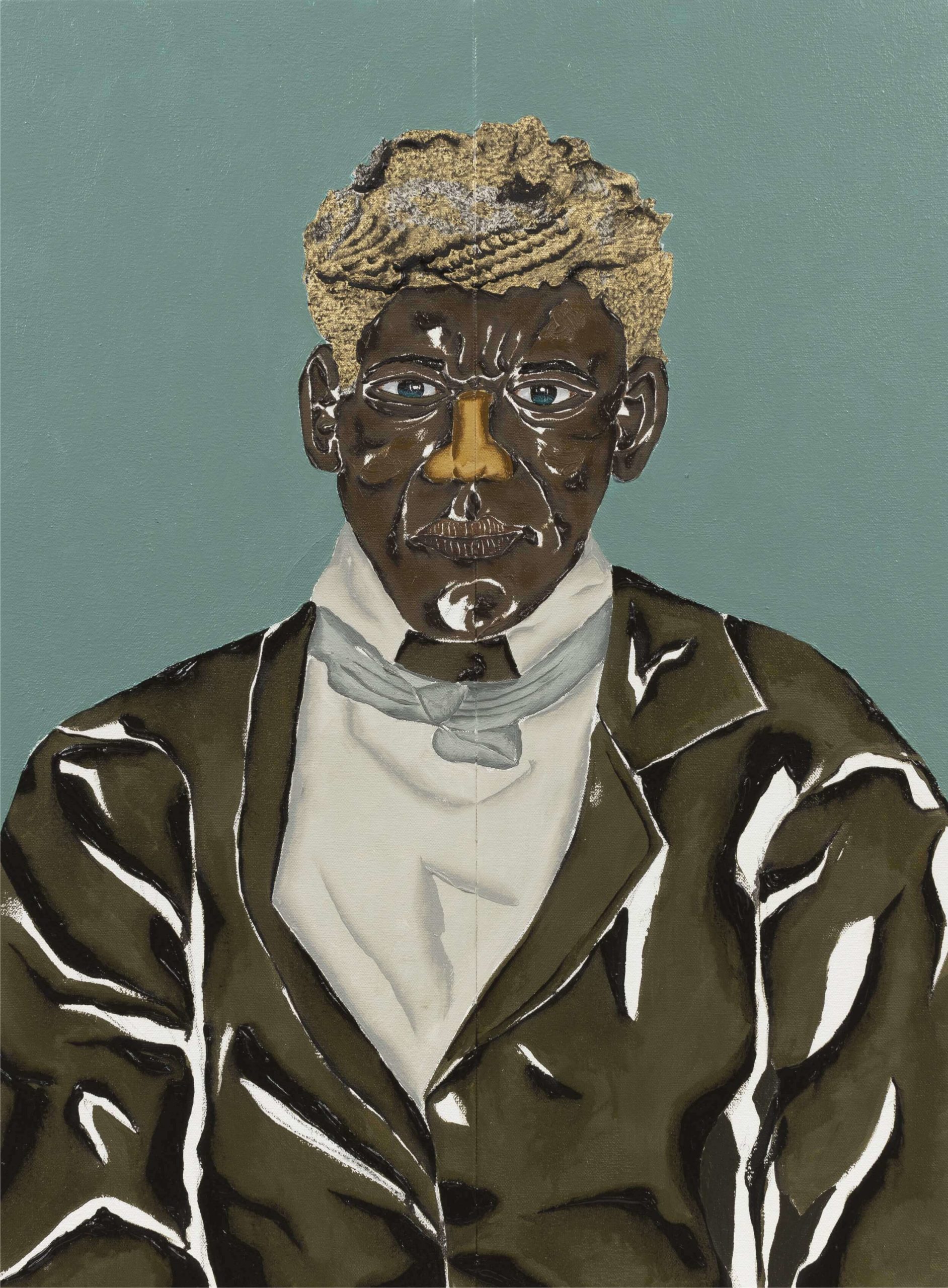

There is an importance of the representation of this King, Reis Malunguinho, as an important historical figure in the counter-colonial struggle in the mid-nineteenth century. His portrait, which is being reproduced, comes from hearsay that emerged during the imperial period: the crown, which hunted this figure for the misfortunes that his power of articulation generated, described him in order to capture him for 100 contos de reais.1 However, its unknown side was so rare that not even those who pursued it knew about it.

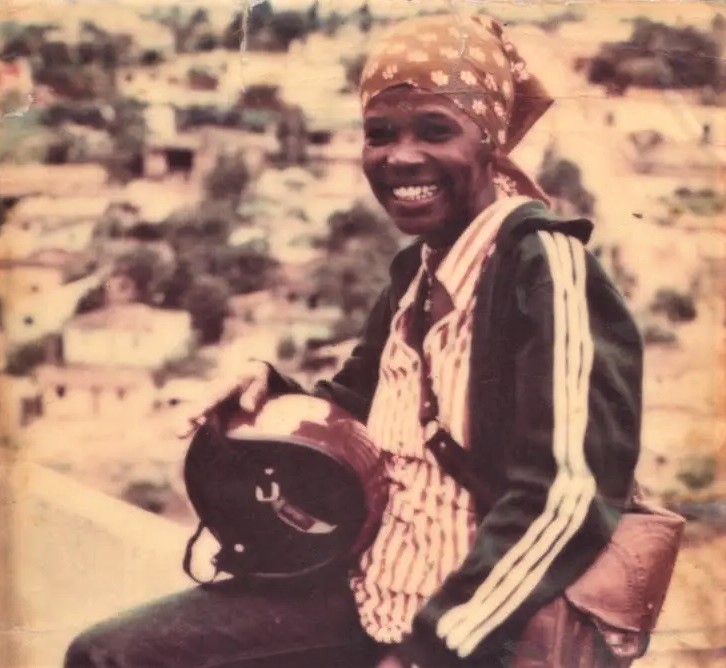

Through ignorance of whiteness, we see the attachment to a single image. They were deceived by the strategy of the peoples that integrated the quilombo; they did not perceive that the Quilombo of Catucá, the sacred mato, was not led only by a body, but that it was raised by the plot of so many malungos. The Kimbundu would give origin to the term malungo, which with the whole colonizing process would receive the suffix -inho that, in the Portuguese language, has a semantic value that can be associated with a diminutive value, sometimes also with pejorative value or attenuating negative adjectives; sometimes, showing sarcasm, others, expressing precision. It also appears as a place of delicacy and, even, in an affectionate way.

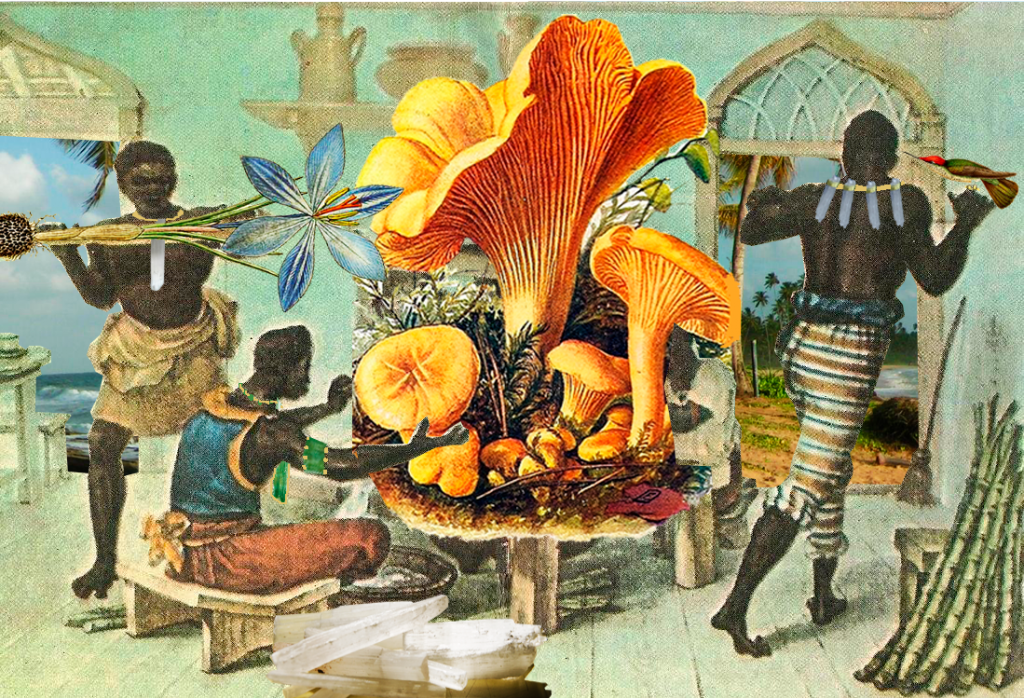

The Reis Malunguinho, thus written in plural, refers to all those who were Malunguinhos in life: leaders of Quilombo do Catucá who became "enchanted" and today are spirits that act in defense of the people who reinforce their undeath, by practicing their cults in the catimbó—a religion of indigenous origin that porously incorporated traces of Afro-religious cults (e.g., quimbanda). Catimbó is a union of Ka'a = bush and Timbó = white vapor; the term can also be related to the act of smoking a pipe, making smoke.

A quilombo so strong that it snaked through the suburbs of the city of Recife in Pernambuco, growing between the waters of the Capibaribe and Beberibe rivers, cutting through sugar mills and entering the bush that embraced a territory of another Brazilian state, Paraíba, more specifically, the city of Alhandra, where to this day it is possible to find traces of the passage of masters and mistresses catimbozeiros.

It would be absurd to continue to represent Reis Malunguinho as a single body. His drive is felt in the echo of many and makes it impossible to capture his image. The representation of a leader, as happened with Zumbi dos Palmares, could serve Malunguinho as a political and historical figure; however, his active cult only further reflects his wanderings that encompass different personifications and identities.

There is then an immeasurable unfolding of his body-prism, where his reflection is associated with a non-centrality, but it does potentiate the Malunguinhos becoming, which is the recognition that Malunguinho is also me.