Seeing and Educating: Marta Traba in Colombian Television

04/11/2023

Marta Traba's work in the country managed to combine art criticism with academic teaching, radio and television programs, magazine editing and exhibition management. She also contributed to the creation and direction of the Museum of Modern Art of Bogota. In addition, her work in favor of the internationalization of Colombian art represented an unquestionable legacy.

In 1984, 20 chapters of Historia del arte moderno contada desde Bogota1 [History of Modern Art Told from Bogota], a program for the once small screen hosted by Argentine art critic Marta Traba Taín (Buenos Aires, 1923–Mejorada del Campo, Madrid, Spain, 1983), were seen. Under the sponsorship of Colcultura, it was the post-mortem transmission of a series that was left unfinished due to her unexpected death on November 27, 1983. A testament that paid tribute to the woman who, during the 15 years of her life in Colombia, shook the artistic scene with her charisma, her provocations, great educational vocation and remarkable knowledge of the arts that she managed to express with great mastery of language. Marta Traba's work in the country managed to combine art criticism with academic teaching, radio and television programs, magazine editing and exhibition management. She also contributed to the creation and direction of the Museum of Modern Art of Bogota. In addition, her work in favor of the internationalization of Colombian art represented an unquestionable legacy.

While living in Colombia, between 1954 and 1969, Marta Traba's aesthetic judgments initially established historical relations with European modernism, basing their evaluation on universalist ideals.2 This framework of analysis took into account what she had learned with Jorge Romero Brest3 in Buenos Aires and from the sociology of art of Pierre Francastel in Paris. Then, in the mid-sixties, she redefined her critical-theoretical framework to think about the visual arts from a local and Latin American point of view. The Cuban Revolution and U.S. policy for Latin America influenced her anti-imperialist vision of the region and her reflections on what distinguished Latin American art from the U.S. artistic manifestations4 that at that time dominated the contemporary art scene. Her ability to criticize or confront without concealment caused the Colombian government to declare her expulsion from the national territory for a pronouncement that they considered an intervention in the internal politics of the country.5

The Means and the Message

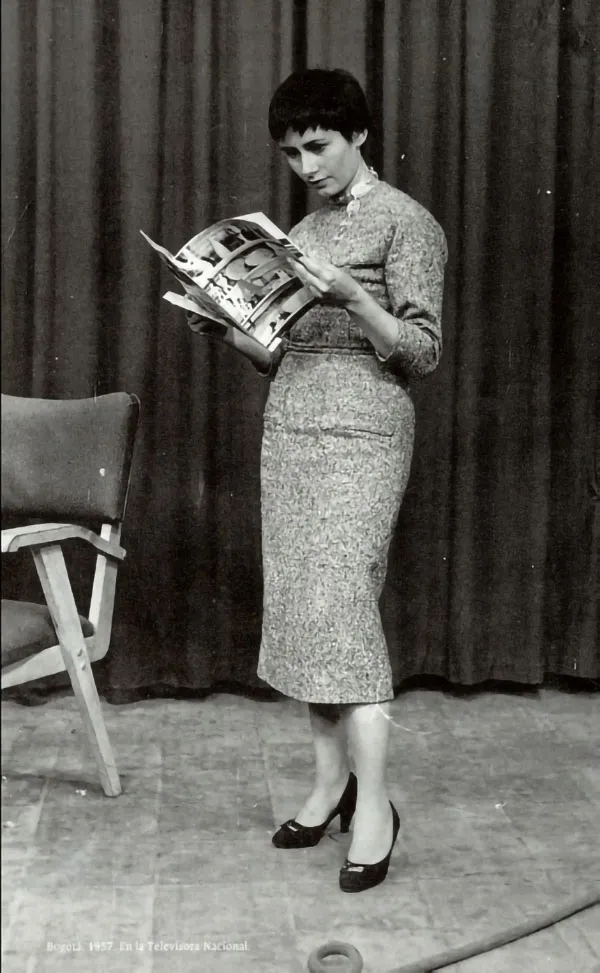

Signs of her thinking's drift can be noticed in her trajectory through Colombian television. Coming from Italy, Marta Traba arrived in Bogota in 1954 with her husband Alberto Zalamea and their young son Gustavo, almost three months after the first television broadcast in the country. This newborn communication media welcomed her and her quick incursion into it made her one of the pioneers.

On June 13, 1954, television was launched with the national anthem of Colombia and the words from the palace of General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, President of the Republic (1953-1957), who had staged a coup d'état with the support of some factions of the Liberal and Conservative parties. Those first images were seen in cafés and bars, and in homes that, due to their purchasing power, had a TV receiver.6

There are two circumstances that explain Marta Traba's entry into public television. The sociocultural circle of her husband's family provided her with spaces of sociability with liberal politicians and intellectuals that facilitated her rapid immersion in television, newspapers, magazines, and radio—particularly the cultural radio station HJCK. El mundo en Bogotá (1950)—relationships that the young couple nurtured from Paris where a select group of Colombian writers, politicians, architects, and journalists resided, with whom they shared interests. Friends of hers encouraged her to stand in front of the cameras and speak on air. She believed that television was an exceptional means of cultural dissemination to carry out a critical formative work, which provided guidelines for evaluation and didactics for that purpose.

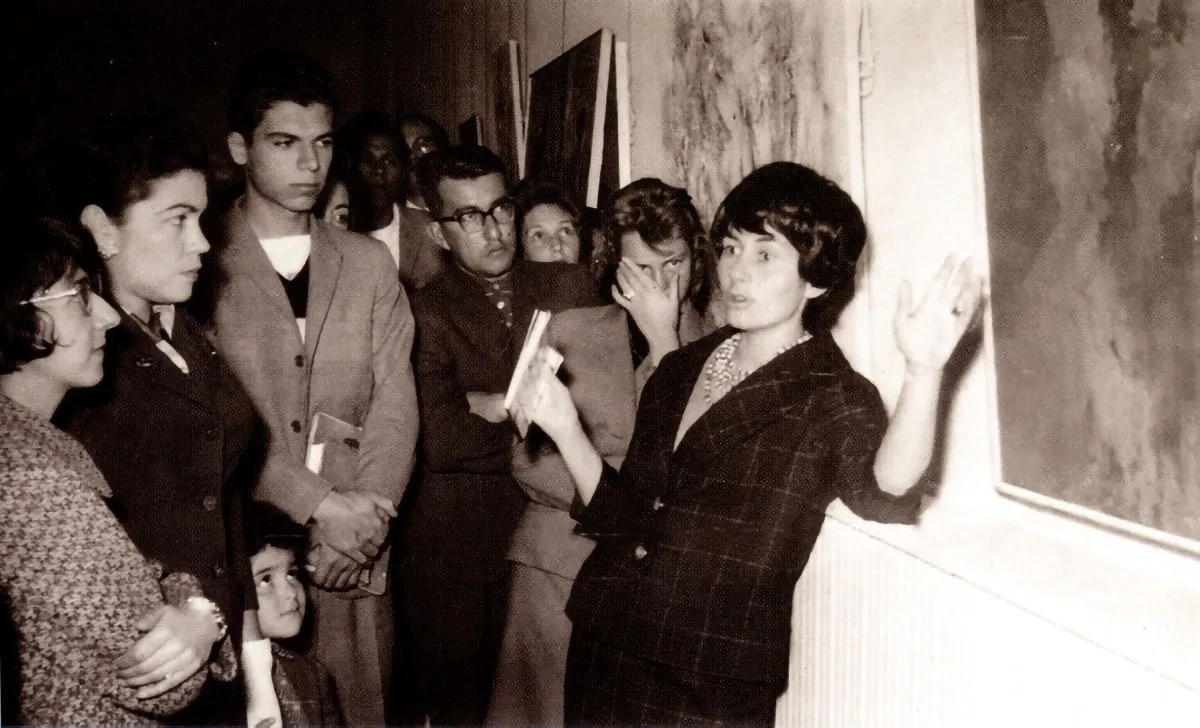

For Marta Traba it was counterproductive that the artwork was treated mainly from a literary point of view, that laudatory, hyperbolic or prejudiced texts were published, which, for her, were detrimental to the formation of an audience. Her vocation was to transmit knowledge, with great mastery of the subject and the gift of the spoken word, about the works she had received in her studies, readings and travels, as well as of being a spectator of museums, theaters and television in other countries.

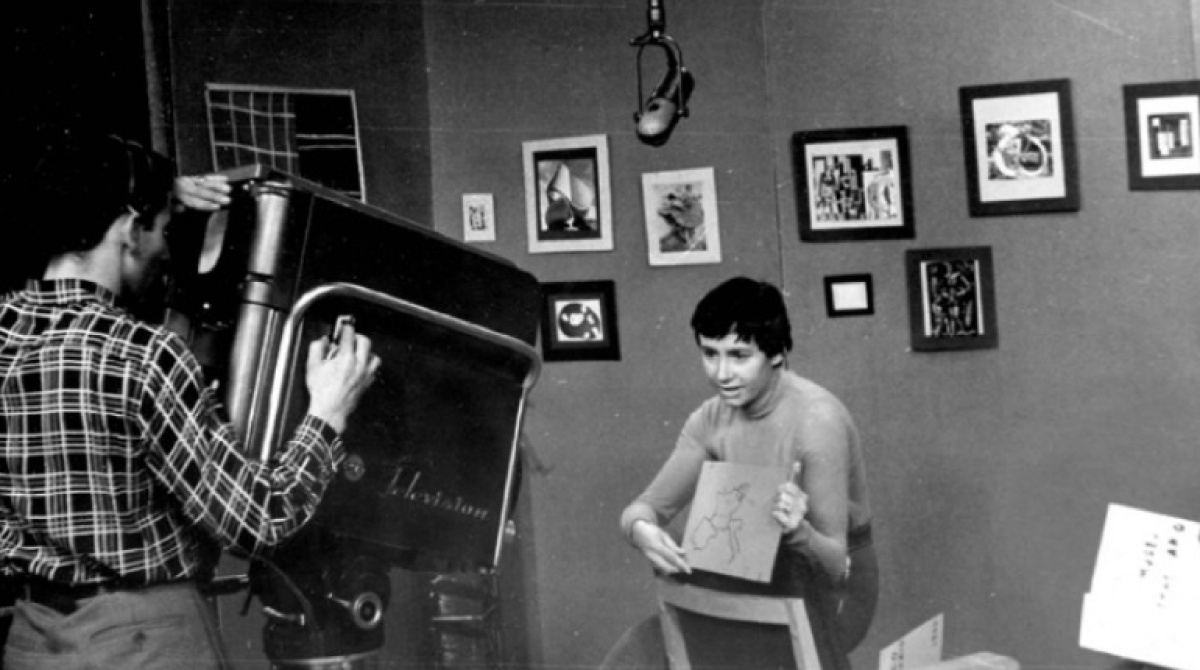

Artist and researcher Nicolás Gómez Echeverri pointed out that Marta Traba's first appearances on television took place at the end of 1954. She was invited to the program La rosa de los vientos to talk about her travels in Europe. Then, in December of that same year, the press highlighted El museo imaginario in which she showed reproductions of European works of art, seen in black and white, accompanied by a text.7 This program probably has its starting point in the ideas of André Malraux, set out in his book The Imaginary Museum (1947), which called for the creation of museums without walls by grouping together photographic reproductions of various kinds. Bringing images of the past closer to people for their knowledge and re-reading was an underlying intention of the book and the television program. In one of the photos included by Gómez in her book En blanco y negro. Marta Traba en la televisión colombiana 1954-1958, you can see the plates attached to the wall of a precarious recording set of the former Radiodifusora Nacional de Colombia where she improvised an exhibition. Marta Traba, facing the camera, holds one of these reproductions as she comments on it, acting as a guide to her own museum. An eloquent photo from Cromos magazine, for a 1956 report, shows her sitting on the floor of her house, browsing through a large album of images of artworks, her own imaginary museum, collected during her travels and which must have been the basis for her art history programs and courses.8

Marta Traba's presence in Colombian television, while she lived in the country, can be framed between 1954 and 1966. The difficulty of establishing the specific periods is due to the scarce film archives that survive. At that time, the broadcasting was live, without filming, and that is why many of those broadcasts no longer exist today; also due to the loss of archives or those to be recovered. However, thanks to the digitization work of Señal Memoria's film archive,9 it is possible to expand Traba's footprint in this medium. As a result of this process, an edition of the program A control remoto in which Marta Traba leads a tour through the rooms of the Museo Nacional de Colombia is available online.

Marta Traba at the Dawn of Educational and Cultural Television

In 1983, she returned to television, the year in which she finally was granted Colombian nationality and, by a fateful destiny, that coincided with her death. She served as a correspondent for Globo Television, reporting on art from different parts of Paris, and recorded the series Historia del arte moderno contada desde Bogotá, when color television was a great novelty. Just four years earlier, Colombians had been introduced to the new system with an address by then President Julio César Turbay Ayala11 (1978-1982). This indicates that Marta Traba's educational and cultural work in public television marked the beginning and the end of her relationship with Colombia.

After the program El museo imaginario and since 1955, several programs were produced whose exact starting dates are not yet known: on Mondays, Historia del arte was broadcasted; on Wednesdays, El ABC del arte, and on Fridays, Una visita a los museos. A report in Cromos magazine illustrates the significance of their production. During her year-end vacations in 1955, she sought to document herself and stock up on books and graphic material so as not to fail a television audience that at that time, by return mail, was showing its support. This is how Marta Traba put it:

«I am committed to improve my lessons every day, out of professional honesty, and to correspond to the trust placed in me by the public. The topics will change a little this year, within my specialty, of course. On Mondays I will do art history. I will begin with Leonardo, followed by Michelangelo and Raphael. By the way, I have proposed an idea, which seems to have been well received at the TV station. When I finish the course on Leonardo, I will invite four specialists to close the series of lectures and complement them. Then a contest will be opened among the audience to award the best essay on Da Vinci. And so on with the others.» [13]

These three programs were in line with the interests of the directors of Televisión Nacional de Colombia, who wanted to turn this medium into a "vehicle for cultural dissemination" and "autonomous artistic expression." They were aware that it was necessary to train an audience and a human team of scriptwriters, scenographers, in the new television language.14 In 1955, among the various work fronts, they declared that a fourth part of the program should be educational and cultural. Perhaps, for that reason, in this year Marta Traba's appearances on the small screen increased with the three mentioned programs. She even attended the acting course, based on Stanislavski's and Meyerhold's methods, given by the Japanese theater director Seki Sano at the Instituto de Artes Escénicas, created by the entity to train the acting craft of what was called tele-theater.15

Photographs known from these programs as well as press articles manage to recover some of their characteristics. Marta Traba acted as cicerone in Una visita a los museos. In his research, Nicolás Gómez mentions that she used small reproductions, mapamundis and books to make a guided tour of European museums that she herself had visited, showing their most relevant aspects. El ABC del arte was focused on the Colombian artists she invited to the studio. A good way to complement her interpretations was to hear the motivations behind their works. In the photos you can see a small recording studio and the scenography that was resolved with a backdrop and the easels on which the paintings were placed in front of the camera. This space housed the cameras and technical equipment that was brought from Cuba.

For example, in ABC del arte with Colombian painter Marco Ospina, in 1956, we can see three paintings on easels, one from the figurative period and two abstract works, a language he had been exploring since the 1940s. The image shows Marta Traba, dressed in a foulard, an element of distinction, interviewing Ospina, also a professor at the National University of Colombia. In that same year of the television show, Ospina exhibited at the National Library of Colombia16 and Marta Traba, who was already publishing her reviews in newspapers with a large national circulation, wrote him a review that, while highlighting the painter's interest in seeking the internal rhythm of his abstract painting, stripping it of volumes or known forms, complained that some sketches of abstract murals depended on forms that told a story. In short, what she emphasized most about his painting was the way it configured its own order of lines, shapes and flat colors. But Ospina's reaction to this type of commentary is indicative of his reluctance: he published an article entitled “La crítica de la crítica”17 as an outraged response to Marta Traba.

An Educational Screen for Art History

In interviews at the time, she emphasized that cultural television was opening a classroom in everyday homes. She valued its reach to connect as a "professor" with people who lived in remote corners of the country that even she didn’t know. This was the case of the Art History Course that began in November 1957 with broadcasts on Friday nights. People who wished to enroll had to apply by letter with their contact information and age. For ten months she developed a methodology that allowed for a more direct relationship. By mail, on a weekly basis, they would receive a mimeographed lecture to be read before each program.

According to her, the course would have two types of students: some would be listeners with the right to attend the lectures and others would be attendees who, in addition, would have to complete a monthly practical work based on a questionnaire that she herself prepared. In the end, those who fulfilled this requirement would receive a diploma of attendance. Marta Traba emphasized that her intention was to broaden the limited university circuit that existed in Colombia and cover places where it would be almost impossible to attend a course of this nature:

"It seems unnecessary to emphasize that this is not an art history read chronologically from Altamira to the present day, but a careful selection of themes whose ultimate purpose is to exalt the value, importance, necessity and diversity of the artwork as the ultimate expression of the human spirit." [18]

This course, which in 1958 would reach 640 students nationwide, as Marta Traba pointed out,19 would inaugurate an educational television in art history, which, as Florencia Bazzano suggests, can be placed in the same genealogy where Sister Wendy Beckett or Robert Hughes take place.

Around 1958, Ciclo de conferencias was issued with a group of intellectuals in the studio. At that time she mentioned that a group of priests from the department of Chocó wrote her because they were giving classes based on the lectures periodically sent by Marta Traba to the people enrolled.200 Between 1965 and 1966, Puntos de vista, a cultural program of the private channel Teletigre was broadcasted, including interviews, commentaries on books, lectures, theatrical productions or about the plastic arts. She felt insulted by the interference of the police in a program to which she had invited students from the National University of Colombia, who were stigmatized for stirring up subversion. She then decided to cancel this program. This event became the prelude to Colombia's expulsion pronouncement accusing her of intervening in the country's internal politics.

In the last year of her life, she dedicated herself to giving lectures, writing about 20th century Latin American art21 and presenting the exhibition Arte de la calle, arte del taller in Paris with Colombian artists. But the television project that excited her was the recording of La historia del arte moderno, contada desde Bogotá, which was broadcast on national television in 1984 as a tribute to Marta Traba. This series covered various tendencies of the historical avant-garde and those of the 1960s.22 These programs, such as those devoted to post-impressionism, cubism, hyperrealism, sensitive geometry, weaving in art or non-figuration, meant a reconsideration of her own positions, as in the case of the episode dedicated to conceptual art. At that time, Traba was a staunch critic of the idea of "being up to date" with the metropolitan centers of North American and European art. It seemed to her, for example, that certain conceptual art that made use of text was mere amusement considering the high illiteracy rates in Latin America.

The curious thing about this eighteenth program is the way it was produced. She decides to begin it from behind the scenes, appearing in the middle of the technical team. They show the cameras and monitors, which evidences the "process" to carry out each program. Marta Traba's image is that of a conventional lady who plays with improvisation, error and deliberate carelessness that expose the realization. The voice of director Rodrigo Castaño can be heard giving indications while the assistant appears in the frame pasting on a flipchart each one of the slides that Marta Traba talks about in a freer way, with a lot of self-confidence, without being tied to a precise speech or pre-established guidelines. This other imaginary museum is configured with images cut out from magazines and catalogs.

What is noticeable there is a didactic resource that reinforces Marta Traba's interest in taking into account the viewer, who was not exactly a scholar in the field. In short, she proposed to articulate Latin American artists among European and North American artists "so that they would be placed where they should be."23

Following the task of her television programs in the 1950s of laying the basis for understanding the artistic values that for her were the foundations of art in the West, she sought in her later programs to insert Colombian artists and those from other Latin American countries into art history, which to a large extent referred to the centers of greatest dominance in the plastic arts. Those centers that were noted as important at the beginning of her educational work, in her last years she repositioned them to give a political place to Latin America in a macro narrative of art modernity.