Cuba: The Higher Arts Institution — The Fruitful Seed

04/10/2023

The space is often cited as being less affected by the political ebbs and flows of the Cuban State, where freedom of speech and expression are largely maintained, thus creating the perfect grounds for creative growth and blossoming.

The Instituto Superior de Arte [Higher Arts Institution] (ISA) has been at the forefront of the Cuban art scene since its establishment in 1976. It has been celebrated as the driving force behind the country’s artistic renaissance—known more widely as the New Cuban Art movement of the 1980s—and as the cornerstone of Cuban artistic continuity through the teacher-student relationships that the institution cultivates. The space is often cited as being less affected by the political ebbs and flows of the Cuban State, where freedom of speech and expression are largely maintained, thus creating the perfect grounds for creative growth and blossoming.

Throughout this text we will traverse the ideas and frameworks that made ISA a reality, we will consider some of the key individuals that emerged from it, the collectives the institution fostered, and how the space became a centre of nurturing and resistance.

In 1961, Fidel Castro, the leader of the Cuban Revolution, outlined his cultural policy for the country through one of his most infamous declarations: ‘Words to the Intellectuals.’ Castro outlined that the Revolution would not seek “to stifle art or culture, because one of the goals and one of the fundamental aims of the revolution is to develop art and culture, precisely so that [it] truly becomes the patrimony of the people.”1 The speech delineated that it was every artist and intellectual’s responsibility to educate the citizens of Cuba to “escape inherited colonial shadows of obscurantism, superstition, and falsehood.”2 This approach to art and culture changed throughout the decades according to the social, economic and political needs of the island. In moments of prosperity, such as immediately after the triumph of the Revolution, the arts were championed and pushed to develop. It was at this moment that the first steps towards the creation of ISA were taken.

Until the 1960s, the only formal arts institution that existed was the San Alejandro School of Fine Arts, set up by French artist Jean Baptise Vermay in 1819. In 1961, while Fidel Castro and Che Guevara were enjoying a game of golf in the rolling hills of Cubanacán, they decided that the setting was perfect for a new national school for the arts. In that moment, the Escuela Nacional de Artes (ENA) was born. ENA can be seen as the first edition of ISA. In the same year, the established Cuban architect Ricardo Porro was tasked with creating the ENA within two months. He looked towards Vittorio Garatti and Roberto Gottardi, “two Italian architects Porro had met in Venezuela,” to help him realise this complex initiative.3

No article on ISA is complete without a brief comment on its extraordinary architecture. Material scarcity implied making the structure predominantly out of brick, ceramics, and terracotta (imported from Italy). The school’s winding structure encapsulates the different areas taught, such as dance, music and the fine arts. The soft undulating cupolas reflect the sumptuous curves of a woman, the winding shapes echo musical notes, and the movement generated by the edifices mirror a dancer in motion. Unfortunately, due to the difficulties of importing Italian terracotta, a shift in the Government’s focus from the arts and culture to the military during the missile crises and the ensuing embargo, a large part of the school remains incomplete.4

Cuban artists such as Raúl Martínez and Antonia Eiríz began teaching at ENA, as it was seen as a space where “full freedom of expression was retained.”5 However, following the political difficulties seen in Cuba in the 1960s, a hard-line approach was taken against culture, and from 1970 to 1975, Cuba experienced what is now infamously known as the quinquenio gris, the five grey years.6 During this period, many artists left the island, or in the case of Umberto Peña and Antonia Eiríz, refused to paint or create art again. In 1976, when Cuba’s economy and political standing in the world stabilised through its attachment to the Non-Aligned Movement, the quinquenio gris came to an end and the Cuban State realised it had to make a radical change in its attitude towards the arts. They started the process by dividing the Ministry of Education and Culture into two separate departments and appointed Armando Hart Dávalos and María Leiseca as the Minister and Vice-Minister of Culture—allowing the cultural sector more autonomy. The next stage was the reinvigoration of the ENA and its transition into ISA, broadening the scope of the arts, allowing ISA to be a space not just for the refining of artistic technique but a space where art theory and critique were at the heart of the curriculum. As Cuban art historian Rufo Caballero explains, “As we know from elementary political theory, when power feels secure, strengthened by its dexterity to reach out to the people, it will allow itself the indulgence of recognising and even applauding critics.”7 According to former Minister Armando Hart, “the ISA was... a very beautiful act of creation resulting from the cultural policies of the Revolution.”8

In a collection of memories by Armando Hart titled Fe: trazos en mi memoria desde la ética, he explains that the main reason for the creation of ISA was to cultivate a space that housed the rich artistic tradition that already existed in Cuba and to carry it forward.

«The joint work of teachers and students in this direction has favoured the development of creative independence, an essential factor to ensure our young continue the relay race, having assimilated our best traditions, whilst also promoting its necessary renewal.»[9]

This relationship between teachers and students mentioned by Hart became the catalyst behind the artistic explosion in Cuba throughout the 1980s until today. Although the first generation to graduate from ISA in 1981 generally remark that their work was ground-breaking in spite of the Cuban cultural frameworks that existed. A policy that ensured that artists were guaranteed employment in the institution after graduation meant that staff at ISA became dramatically younger after 1981.10 Those who had been students and part of the New Cuban Art movement, were now teachers themselves.

The Relay Race: Passing the Batton

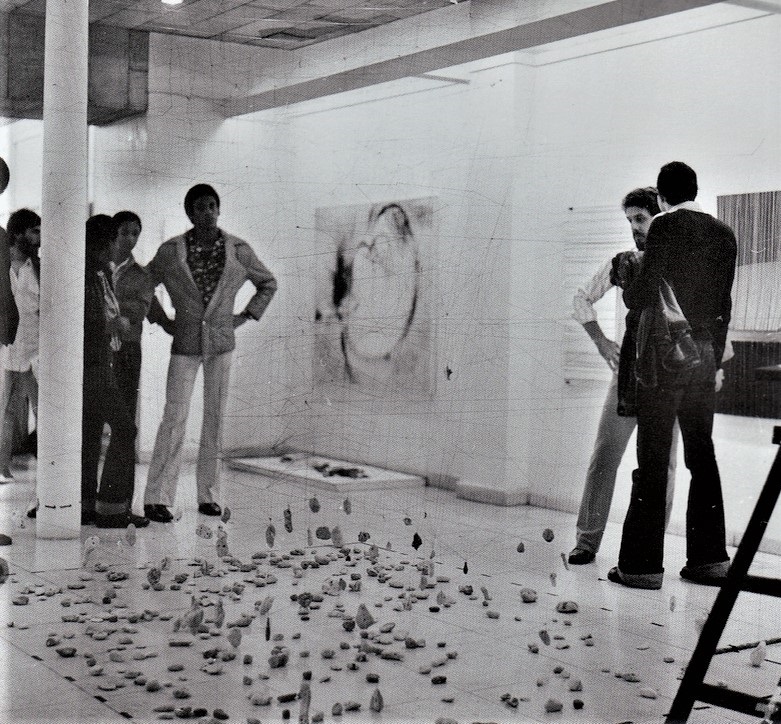

From 1981 to 1990, three distinct generations of Cuban artists have been outlined by Luis Camnitzer in his book New Art of Cuba. Each group is defined by the year the artists graduated from ISA and who their teachers were. The first generation of ISA graduates is most widely known as the Volumen Uno group, named after the exhibition that was staged in January 1981. The group of eleven was formed on the grounds of ISA and, despite their Soviet-structured curriculum, the artists shared critical thought and content, creating ground-breaking work. Volumen Uno included José Bedia, Juan Francisco Elso Padilla, José Manuel Fors, Flavio Garciandía, Israel León, Rogelio López Marín (Gory), Gustavo Pérez Monzón, Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, Tomás Sánchez, Leandro Soto, and Rubén Torres Llorca. Many of them went on to become formidable professors at ISA and influenced the following generations. In her book To and From Utopia in the New Cuban Art, Rachel Weiss outlines a key pedagogical strand descending from Flavio Garciandía.11

Flavio Garciandía established himself in the early 1980s as an artist whose work traversed styles and periods. His most famous pieces range from the photorealist painting Todo lo que necesitas es amor [All You Need is Love] to his Tropicalia series, where the artist inverted the use of the hammer and the sickle to demonstrate that “there was a revitalisation of socialism, but in turn it constituted a 'third world' carnivalization of the symbol to break its orthodoxy and make it participate humorously in the multiplicity and contradictions of the South.”12 Garciandía’s focus on the kitsch, the subversion of cultural icons, and a blurring between the real and the reconstituted influenced many Cuban artists who were his students. Of particular note are artists from the 1990s group (falling outside the three generations outlined by Camnitzer), Abel Barroso and Los Carpinteros. Abel Barroso’s Café Internet del Tercer Mundo [Internet Café for the Third World], created in the artist’s signature style of using almost entirely wood and ink engravings, illustrated the infamous lack of internet access in Cuba. Barroso created a space that worked like a real internet café but where people communicated through his works instead of computers. The relationship between the medium and the subject type is reflective of Garciandía’s influences. While he used papier-mâché or paint to substitute photography or plastic, Barroso used wood instead of technology. Similarly, Los Carpinteros subverted their materials in their earlier works such as Ciudad Transportable [Transportable City]. The work was composed of 10 tent-like structures made from synthetic fabric, aluminium tubing, and transparent plastic windows. The structures were based on famous edifices from Havana’s skyline. By transforming the medium from brick and mortar to ephemeral materials, the group made a commentary on imported architecture and touched on issues of immigration and transient living conditions.

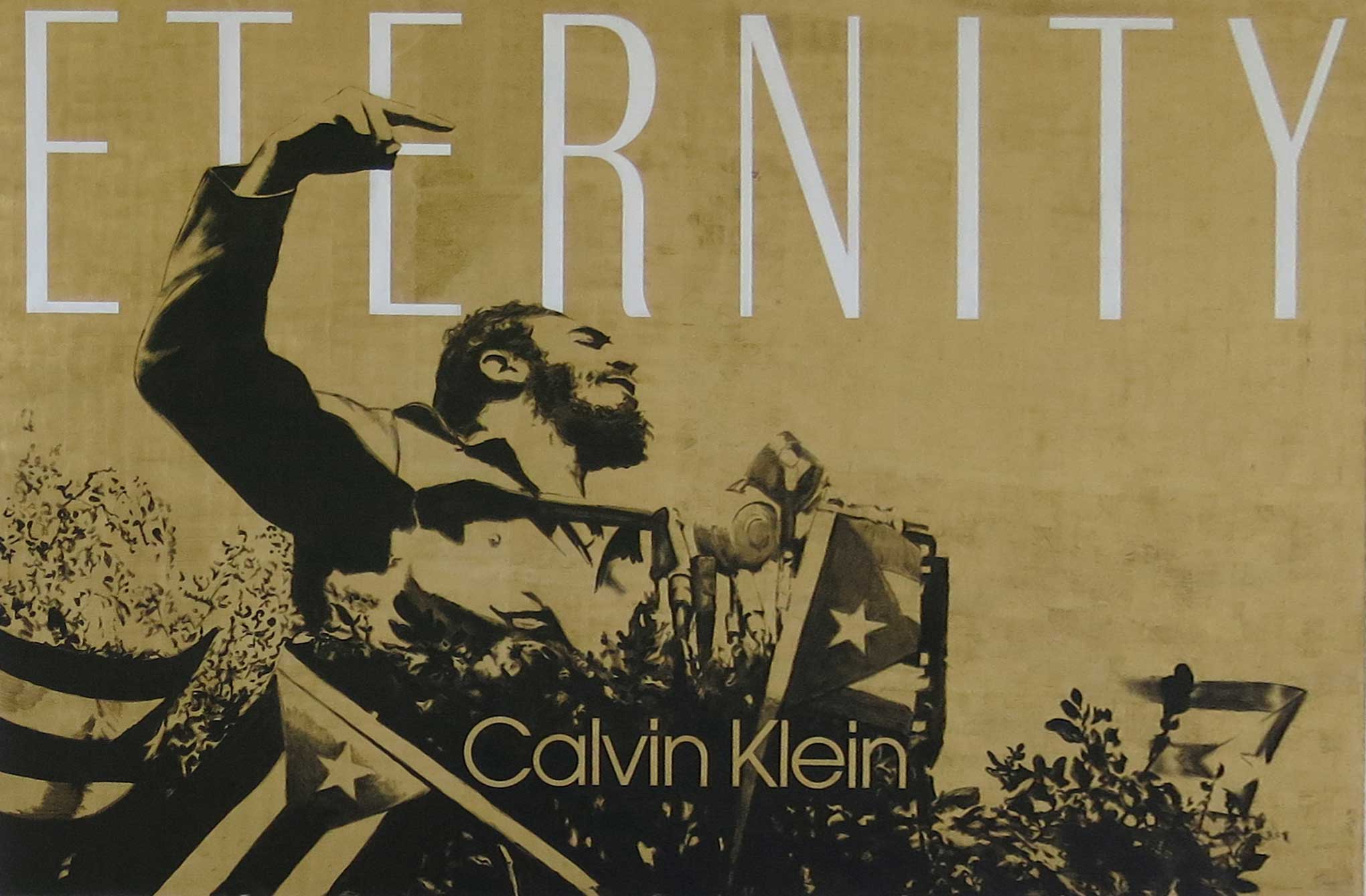

Camnitzer explains that, while the first and third generation of ISA graduates had more of a tendency to work in groups, the second generation, made up of artists such as Humberto Castro and Consuelo Casteñeda, preferred to work alone; however, both went on to teach at ISA. Casteñeda is often singled out as being one of the most influential ISA professors of her generation. Camnitzer describes her work as initially being appropriation with little transformation.13 Casteñeda took the styles of artists such as Lichtenstein or borrowed from Greek sculptures, reproducing them within a Cuban context. The presence of the Western art historical canon in her work functioned on two levels: firstly, by changing the context of famous pieces she was feeding into the reinforcing of a Cuban artistic identity and, secondly, she produced large-scale works that art students usually would only see as small reproductions. Her focus on key details in the works allowed technique to be at the forefront of her pieces. In passing the baton to the next generation, Casteñeda greatly influenced artists in the third generation, such as those that were part of the ABTV collective: Tanya Angulo, Juan Pablo Ballester, José Ángel Toirac, and Ileana Villazón. One such example is the group’s piece Nosotros (after Raúl Martínez), which included portraits of the group done in the style of Raúl Martínez. In their own individual practices, Casteñeda’s influence can still be traced. José Ángel Toirac frequently reproduces popular culture figures in his work, even going as far as appropriating commercials such as Calvin Klein’s Eternity and superimposing it with images of Fidel Castro.

A Collective Pedagogy

While individual teachers had a lasting influence on ISA graduates, some professors took a more collaborative approach to their teaching styles. This can especially be seen within the third generation. Artists such as Lázaro Saavedra and René Francisco Rodríguez worked in groups or pairs during their time as students at ISA, Saavedra in Grupo Puré (Adriano Buergo, Ana Albertina Delgado, Ermy Taño Carrillo, Ciro Quintana, and Lázaro Saavedra), and René Francisco as part of a duo with Eduardo Ponjuán. Collective work in this generation varied from working on individual pieces that fit into larger exhibitions, to working on the same pieces together in stages.

This collectivism filtered through to the third generation’s teaching methods. As a professor at ISA, Lázaro Saavedra formed the performance group ENEMA in 2000 with his students Fabián Peña, Adrián Soca, Lino Fernández, Pavel Acosta, Edgar Echavarría, David Beltrán, Alejandro Cordobés, Janler Méndez, Nadieshzda Inda, Zhenia Couso, Hanoi Pérez, Rubert Quintana, and James Bonachea. Performance became a popular medium from the 1980s onwards due to its accessibility and the few materials needed to carry out works. ENEMA saw themselves as metaphorically cleansing the Cuban art world of its “shit”. Their performances were “based on physical ordeals, tests of endurance, and quietistic displays of pain.” Pieces such as Ustedes ven lo que sienten/Nosotros vemos called upon the works of other famous artists such as Marina Abramovic’s You See What You Feel/ We See.

As a professor at ISA, René Francisco created the group Galería DUPP (Desde una Pragmática Pedagógica) along with his students. Between 1997 and 2001, the group had various iterations. The artists involved included Beverly Mojena, Joan Capote, Inti Hernández, Juan Rivero, David Sardiñas, Omar & Duvier, Ruslán Torres, Junior Mariño, Alexander Guerra, Mayimbe, JEF, Wilfredo Prieto, Michel Rives, Iván Capote, Yosvani Malagón, Glenda León, and James Bonachea. The group’s activities varied from pieces exhibited in the Havana Biennial such as Uno, dos, tres… Probando, where the collective displayed 100 iron-cast microphones on the Malecon wall, to the pedagogical project Casa Nacional where the members lived in large, dilapidated complexes known as solares and helped residents improve the conditions of their buildings and houses by using their artistic skills.

If, as described by former Minister of Culture Armando Hart, Cuban art is a relay race, the baton is Cuban artistic heritage and the track or field is undoubtedly ISA. As seen throughout the article, ISA became a space for sharing knowledge and a hive for fostering a collaborative spirit. Professors and students engaged in a symbiotic relationship, where hierarchies were often dispelled and (at least for the first 20 years) freed from the restraints of the art market, hence, creativity flourished. The collectives continued with each passing generation. Ruslán Torres built upon his experiences in DUPP and created his own student-professor collective: Departamento de Intervenciones Públicas – DIP (Analía Amaya, Abel Barreto, Douglas Argüelles, Fidel Ernesto Álvarez, Humberto Díaz, Jorge Wellesley, María Victoria Portelles, Tatiana Mesa, and Heidi García).

Today, groups such as La Refriega, featuring 13 active ISA students, have emerged in the 14th Havana Biennial. Although ISA has become more susceptible to the ebbs and flows of political upheaval in Cuba, it is still undoubtedly the fruitful seed that keeps giving.