Self-education: A Drifting Journey through the Gulf of Mexico

10/12/2023

For this mapping, I will talk about four projects: Bruma laboratoria, Ensayo en Sitio, Vivero de Tebanca’s Topote de Acahual, and A la Vera Editorial [...] groups that work with self-education and the questioning of the colonizing forms of progress and order imposed during the last century.

In 2019, I co-founded Bruma, a communal investigation with the maxim "Let's talk about what it means to make art from Veracruz while we drink coffee and traverse our territory." As a result of this, I have been talking with those of us involved in Bruma, but also with other projects that during the last five years have proposed collective, educational, experimental, or whatever you want to call them (because every time I feel that the terms matter less and less), which involve inhabiting and preserving different cities and communities along the Gulf of Mexico. For this mapping, I will talk about four projects: Bruma laboratoria and Ensayo en Sitio in the city of Xalapa, Vivero de Tebanca’s Topote de Acahual in Los Tuxtlas, and A la Vera Editorial in the Papaloapan River basin.

I would like this text to be read as a road trip. I would like those who read me to imagine that we are in a car traveling along a road that runs from north to south and from east to west, the lands that border the Gulf of Mexico, those that are between the sea and the mountains. I want you to imagine how we stop at some points to go to the bathroom or to eat garnachas and how we admire the landscape along the way: we will see that it changes from mild to hot, from dry to humid, or from polluted and smoky to green and rainy.

Why do I want to take you on this trip? First, because it makes me nostalgic: when I was a child, it was very common for me to travel by road in the family tsuru, with the windows down to keep the heat out, with a cooler full of juices, flavored waters and sandwiches of yellow cheese, mayonnaise and ham.

I traveled these roads along the Gulf Coast to visit my grandparents (who lived 12 hours to the north) at least once a year, until it started to become dangerous to travel through all this territory, around 2007: first it was the roads, then some villages and, eventually, in all the cities, towns and communities we started to travel our roads with fear. Life (my life) was transformed and was reduced more and more to inhabiting only the nearby lands.

The second reason for this trip is that I want to take the time to tell you some things and show you some groups of people who have made it possible (for me, for them and others) to go back to their beloved lands through artistic approaches, after many years of uncertainty.

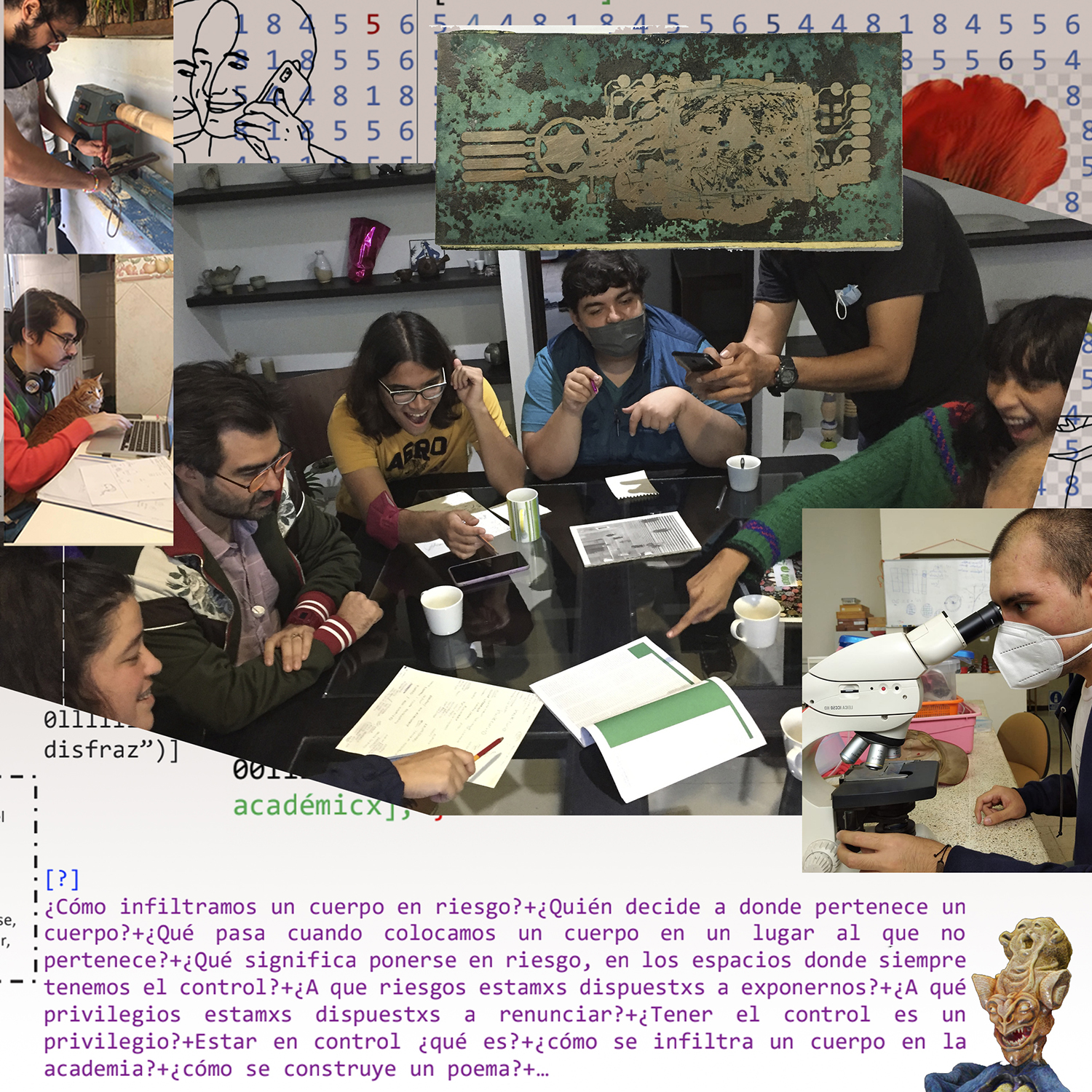

First stop: Bruma Laboratoria

We will start our journey in Xalapa, Veracruz, a mountain city where Bruma is located: a collective formed by artists Leonor Arely Téllez, Rodrigo González (a.k.a. SRGZ), administrator Ramel Rodríguez, and myself, Alejandra R. Bolaños. Throughout almost four years, we have managed art workshops, performance parties, potlucks, exhibitions, talks, and meetings with local agents. We started activities in September 20192 with a post-Duartista reflection, proposing a feminist space to process what had been lived in Veracruz during the last decade. Many things and people have passed through the collective and the program since then, as well as topics, technologies and devices, we have already questioned feminism itself and now we are investigating other things that occupy us, such as practices around care and self-preservation.

The drift or walk is the device that has accompanied us from the beginning, and that we deepened from last year (2022) with the project Sereno Bochorno: a journey of 10 stations, which we did in collaboration with Local Taller, our headquarters space, and that we have continued to develop until now. Throughout two months we met every weekend to go to a specific place, which was activated/guided/performed by different artists from Xalapa that we called for this occasion. We went to a waterfall, to a downtown neighborhood, to a museum, to a hill, to an island, to a colonial fortress, to some reggaeton bars, to a fresh water pool, and we talked in Local Taller's classroom. All spaces between the cities of Xalapa, Puerto de Veracruz, Xico, and Coatepec, in the state of Veracruz.

We wanted to make the journey, the drift, the walk or the travel, a space for study and philosophical thought; we wanted to think in movement: what would happen, how would practices be transformed, when traveling through what we understand as "our territory" after a long time of not doing it calmly? How would one converse in front of a thundering waterfall, in the middle of an industrial port, or in front of colossal Olmec heads?

Thus, walking through these places had to do with the power of doing it in a herd. At the same time, the decision to take to the streets, the mountains and bodies of water was not random: it seemed important to us to embark on a tour of the places where we live, to make walks without fixed formats, to see what was detonated in the memory and personal history in those spaces by giving us the possibility of looking, knowing and understanding with the body the complexities of our territory. And I must say that the walks began after a long period of insecurity on the margins of the pandemic, with a group formed by diverse identities (mostly women, but also children, dissidents and to a lesser extent, men), so we walked from a certain combination of vulnerability and enthusiasm. This ended up leading us to a question that has triggered our insistence on this practice: how can we defend and love a land if we do not know it or if we have already forgotten it?4

These tours had the participation of: Karen Spinoso, Ramel Rodríguez, Luis Morales, Bawixtabay Torres, Rodrigo González, Jimena Ortiz, María Arnaud, Antílope, Eréndira Gómez, Leonor Arely Tellez, Sergio Ramírez, Atenea Castillo, Camilo Cadena, Cynthia Romano, Juan Eduardo Mateos, Melissa Bolaños and myself.

Second stop: Ensayo en Sitio

For our second stop, we continue in Xalapa. Ensayo en Sitio is formed by the duo Rodolfo Sousa and Rodrigo González (a.k.a. SRGZ), and is perhaps the project closest to the exhibition practices of contemporary art of the four projects I present to you on this trip.

For them, it has been important to work around the conversation of "curatorial practice" in the context of Veracruz. That is to say, to designate a person as coordinator and narrative guide of a group of artists who are working or who are in some way linked to the Veracruz territory. This, of course, from a critical perspective towards the local state institutions that dominate the cultural scene and that, due to their bureaucratic nature, make it difficult to show artistic investigations of the present. Adding to this, the precariousness that our institutions have suffered in recent years (and in some cases, corruption and mistreatment) has made showing work in these venues often exploitative, tiring and distressing for the artistic community.5

In this sense, Ensayo en Sitio generates conversations and exhibitions without much bureaucracy and with more immediate actions, producing and accompanying the process of both curators and artists. In addition, as one of the fundamental parts of their practice, they have taken care to move away from the classic exhibition spaces, proposing to occupy places with which they have some kind of affective bond in the city and its surroundings to make their "rehearsals," such as artists' workshops (the garden of the house where I live and Rodolfo's garage) or bars (La Popular and Jaco Jazzy Café).

For example, Hacking from the South (his most recent exhibition), curated by Héctor Beltrán, was activated in the form of a workshop with the participation of artists Agustín Basañez, Bawixtabay Torres, Christopher Grajales, Daniela Rivero, Julio Álvarez, Karla Camarillo, and Leonor Arely Téllez. The workshop days explored the notion of hacking from the south, a term that Héctor is researching at MIT, thinking about localized forms and practices from Latin America that somehow "hack" systems, beyond the understanding of the technological race devised from the West. So it was proposed to explore this theory from the artistic practice of each of the participants (all graduates or students still at the Universidad Veracruzana, the Universidad de Xalapa, and Bruma Laboratoria), to finally expose themselves in an intimate meeting in the garage of Rodolfo's house, during one of the most intense weeks of the last wave of covid.6

The twist that I think is important to highlight is how the curatorial process moved into the educational space with a rather internal outlet, hacking into the conventional art world show.

Third stop: A la Vera Editorial

For our third stop, we will take the highway south. We will take the exit towards the Port of Veracruz, travel for an hour and a half, then take the exit towards Medellín, and finally take the coastal highway straight ahead. We will travel a total of about five hours: We will descend from the humid mountains towards the coast, passing the grasslands of the savannah, the sand dunes, the big city of the port (where we will stop to eat picadas), and all the sugar cane fields, to then go inland towards the banks of the Papaloapan River, where the communities of Tlacojalpan and Chacaltianguis are located, hometowns of librarian and curator Catalina Pérez, who develops part of her practice in this region, through the project A la Vera Editorial.

Since 2020, Catalina has begun to work with a series of provocations (as she sometimes calls her work) as a result of her personal history of growing up in this place and then moving to the center of the country as a teenager, thinking mainly about the educational possibilities and artistic awareness of children in the Papaloapan riverside region.

The first provocation was to propose the creation of a photobook that would talk about and show the river and the different lives that coexist in it, creating art objects that could also be communicated to children and asking: How do we make children accomplices of reflections about the landscape and its imaginary?

To this end, female artists who were registered in this territory (state of Veracruz) were initially invited, but this led to other things, because although they "were from there," they did not necessarily know the specific region of the Papaloapan basin. This complexified the idea of 'territory' beyond borders or what is understood by the nation-state, where people engage with space in many more ways.

This is how A la Vera Editorial has summoned artists (eventually, not only women) who have shared histories throughout the states of Veracruz and Oaxaca, because many populations in this region share social, economic, historical, cultural or emotional dynamics and problems, and particular links with the landscape, the rivers, the beaches and their latent contamination. This gesture has made the idea of the journey very important, especially the journey in common, not only as if it were a documentary photography commission, but of giving oneself completely to the experience of the journey to understand these possibilities mutually.

From these provocations several trips along the Papaloapan have been developed, giving storytelling, photo and radio workshops. In 2022, the photobook Hacemos nuestro río [We Make Our River] was published for free distribution by Casa Gallina, which also resulted in a traveling exhibition with museum formats designed for children and an extensive mediation program. Participating in this publication with poems, illustrations, editorial designs, and photographs were: Catalina Pérez, Josefa Ortega, Adolfo Córdova, Dolores Medel, Abril Hernández, Cuauhtémoc Wetza, Deborah Guzmán, and Cecilia Pompa. Currently, A la Vera Editorial is thinking of activating exhibition devices where artists from Veracruz and Oaxaca (Mexico) collaborate with artists from Belem and San Luis Maranhao (Brazil).7

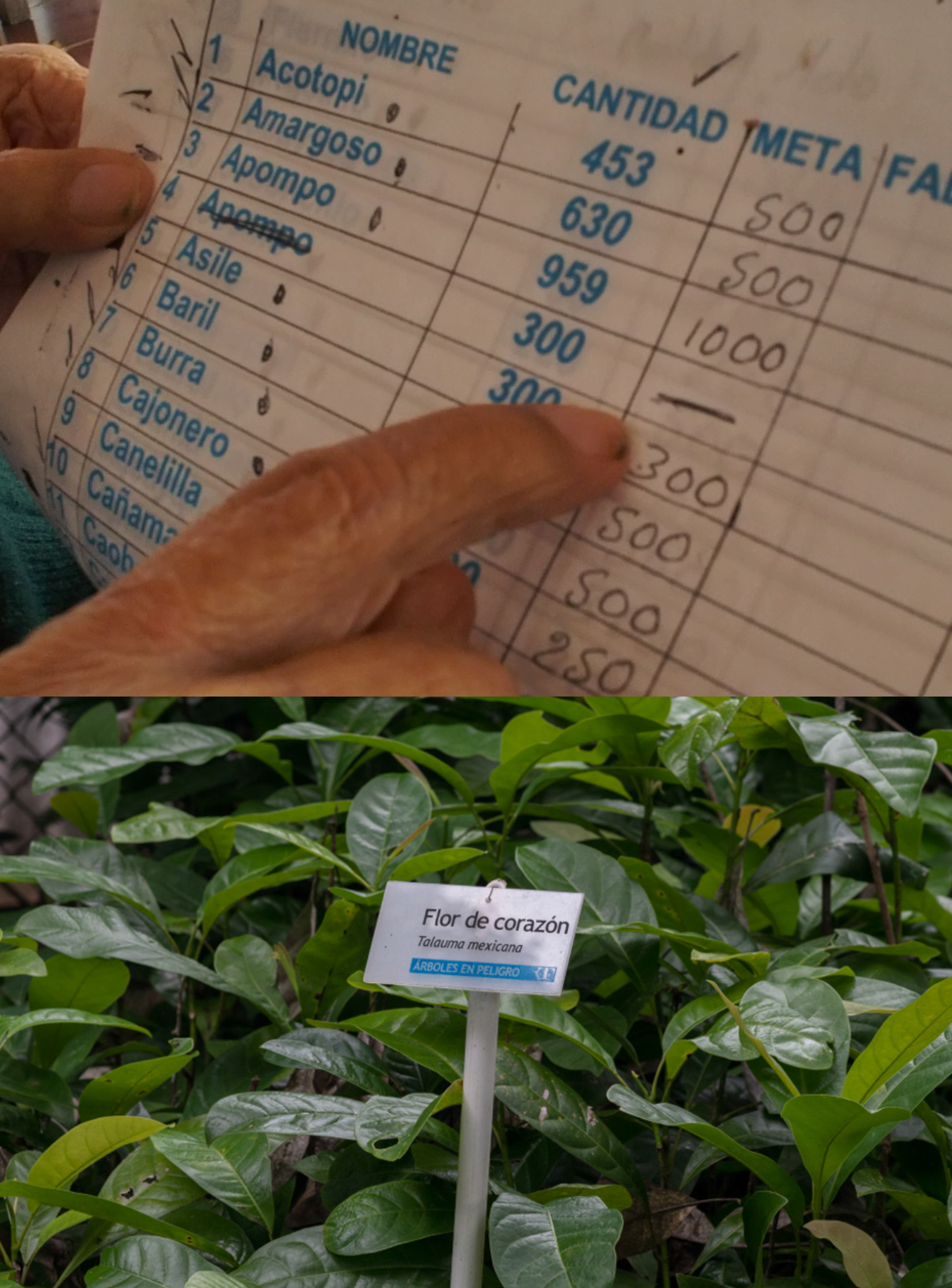

Fourth and last stop: Topote de Acahual of Vivero de Tebanca

Let's go to the last stop of this trip: we will take the Córdoba-Minatitlán highway heading south and then towards Playa Vicente. This last stretch will take a couple of hours. We head to Tebanca, Catemaco, in the jungle region of Los Tuxtlas. Here we find the Vivero de Tebanca, a nursery founded by Antonio Azuela (may he rest in peace) and currently managed by David Antonio Zúñiga. The nursery has been working formally since 2003, growing endemic plants to reforest the jungle around the springs in the area, although its operational history dates back to the early 1990s.

Just as Ensayo en Sitio is the closest to contemporary art practices, this project is perhaps the most distant. There was a 10-day gathering here called Topote de Acahual in 2021, where workshops in drawing, embroidery, writing, publishing, reforestation and health were proposed, intending to create didactic materials about the relationship between the jungle and the lives of its inhabitants.8 Artists came from outside and local agents signed up, and this was the reason why we connected with this place, mainly through the participation of Melissa Bolaños, guest artist from Bruma Laboratoria, who taught a musical composition workshop with the jungle during these days. However, she insisted (as did Jenny Granados, a participant of Topote de Acahual), that the most important thing to know about this space is the work of reforestation, negotiation, and knowledge that has been generated from the nursery itself.9

Vivero de Tebanca reforests springs to ensure the presence and quality of water. They do this by negotiating with the ejidatarios10 and the owners of the land, which is where the springs are located since not all of them are in public spaces. For David, this has been a great task, to re-educate his colleagues about the cultivation practices, as well as the importance of planting trees: because they provide us with oxygen, because they help us to plant water in the soil, and because in their shade other species thrive, both plants and animals, which are essential in the region and which are also often on the list of extinction. All this is in contrast to what he calls "old school", where clearing the forest is commonplace.

With this last idea, we end the journey, linking Vivero de Tebanca to the other projects that have been presented here: groups that work with self-education and the questioning of the colonizing forms of progress and order imposed during the last century.

These forms of self-education are born not to rescue something, but as a possibility of social bonding, with the intention of mutual understanding between people, between peers and disparate, between the diversity of bodies, histories, theories and formations that comprise each specific community, crossed by the multiple movements and migrations of this territory. In Bruma and Ensayo en Sitio, from the artistic community, in A la Vera Editorial, between artists and children, and in Vivero de Tebanca, between land workers.