Everyone Has Something to Learn and Something to Teach

07/03/2023

Artist, educator, and musician Gabo Camnitzer (1984) shares reflections on his experiences as a student and teacher throughout his life, thus evidencing that the common divisions of the professional field of art and education are much more porous than one might think.

Education

Schooling

To be honest, I still struggle with the title of “artist.” My parents work with art, and I grew up surrounded by artists. In some ways becoming an “artist” was the path of least resistance. But I also tend to think of being an artist as more of an orientation or disposition to the world than a profession or title.

I was an incredibly lucky child in many ways, and growing up I had the privilege of spending summers at a printmaking school my father ran. The school was an activity hub for artists from Latin America of a particular political stripe. Artists like Ana Mendieta, Nelbia Romero, Ombú (Fermín Hontou), Esteban Álvarez, Tamara Stuby, Martín Mendizábal, Ana Maria Devis, Fernado López Lage, Carlos Capelán, and others passed through. I found the studio was a welcoming place for children to play and learn, and many of the artists there were loving and generous, becoming almost like relatives. It was in this context that I first understood that making art could be an outlet for more than just expression, but a catalyst for transformation. Part of the structure of the printmaking school was that all the participants would gather for lunch every day. We sat around a big table and all ages were welcome to participate. Everything was discussed: politics, popular culture, art, and education. This model of sociality was incredibly formative for me, and put paid to distinctions between formal and informal education.

But I also had many traditional teachers beyond art, that were influential for me as someone who makes art today. One, in particular, was a Special Education teacher at my elementary school, Mrs. Carrington. As a young person I struggled to acquire language and to read, due to problems with my ears and learning differences. Mrs. Carrington was the person who finally taught me how to read, around age 9. I will never forget the patience and care she showed me. The lesson she taught me is that learning isn’t like flicking a switch, but an ongoing process of transformation is something I still think about daily.

Teaching

I take the continuity between art and education for granted. A lot of this can be attributed to being the child of two anti-hierarchical educators and growing up in the context I did. The distinctions between education and life, art and life, art and education, always seemed quite alien and arbitrary when I did encounter them. This got me in a lot of trouble in school.

I understood early on that everyone has something to learn and something to teach, and that art is a great vehicle through which this knowledge can be concretized and conveyed. As a result, today I don’t make a distinction between my day job working with young people, and my “studio practice.”

Learning

I grew up next door to a park on the border of two very different neighborhoods. This brought people together who were otherwise separated by invisible economic and social boundaries. As a young person, I spent most of my free time there, meeting and playing for hours with friends of all ages, creating worlds and testing limits. This was where I learned much of what I know about the world. I played tag, made sandcastles, learned chess; this is where I learned about privilege, sexism, ableism, racism, and classism, where I first fell in love, had my first joint, etc.

The experiences in spaces like that are so much richer than what a traditional school allows for. I learned more there than in all my formal education combined. Having access to that kind of space, and the care I was afforded there, is something every person should have, whatever age. Settings of informal knowledge exchange continue to nourish me.

In terms of specific artworks that inspire me: Ana Mendieta taught art to 5th and 6th graders in Iowa City after she graduated from art school in the 70s. She worked in collaboration with the students to create some really wonderful moments. An exhibition Amy Rosenblum Martín put together at the Sugar Hill Museum some years ago featured a recording of Ana’s students answering the question “What is a soul?” I found this particularly moving. Ana had been a close friend of my parents. She was killed by Carl Andre while I was very young, but lived on in objects around our house and through stories my parents told me. It was when I had already been working with children for years that I first heard “What is a soul?” I felt such a sense of clarity, kinship and love in encountering it. The unflinching openness with which Ana engaged the children in conversation, and the seamless continuity between her teaching and her studio practice serve as a guiding light for me.

In terms of authors I take inspiration from, pedagogy has been central to my formation. I often return to the work of educators, educational theorists, and practitioners of popular education for inspiration. Figures like Aïda Vasquez, Nadezhda Krupskaya, bell hooks, Gabriela Mistral, Célestin Freinet, José Luis Mariátegui, René Lourau, Fernand Oury, Paulo Freire, Loris Malaguzzi, and Stuart Hall continue to influence me.

Processes

Beginnings

I don’t know how an idea for a new project arises as much as I recognize the feeling that accompanies it. It’s a burst of warmth I feel in my abdomen around my solar plexus. It makes me feel like I need to use the toilet.

Questions

I am too much of a materialist to believe in things like inspiration and intuition, but I have to acknowledge the seeming metaphysical exhilaration of moments of a breakthrough if for no other reason than that they send me to the toilet!

I don’t consider myself someone especially creative, but I am someone who tries to be open to creativity when it comes knocking. Societal structures train the vast majority of people to accept their lot and ignore and/or dismiss moments of creative insight as naïve or frivolous, or beyond their station. This is strategically disempowering.

Openness to creativity is what allows for any possibility of a more just and fun world. Unfortunately, most often the only people who are taught to believe they have the ability to change things are the people least invested in changing them because they already have consolidated power.

Strategies

I always work on multiple projects at the same time. Being able to change gears and focus on something else for a bit allows me to return to what I need to be working on with fresh eyes. I am also a serial procrastinator, but I learned early on that I could leverage my procrastination in productive ways. If I have a pressing deadline, it’s usually a good time for me to work on something that isn’t due for a while.

Procedures

Therapy is integral to my process. Understanding the external factors contributing to my thoughts and sense of self, enables me to better identify and navigate my blindspots, and understand how I am shaped by my experiences and surroundings. Nothing is more dangerous than an artist not in therapy!

I am also always trying to be in the process of learning something new from someone. Whether it be a skill, a language, or an instrument, I rarely get good at anything. It’s all about the process of learning. Being on the threshold of new experiences and knowledge pushes me to think and act in different ways. It also gives me access to productive misunderstandings which often allow me to see things I have taken for granted from new angles.

Dialogues

Collaboration is central to everything I do. Whether it is in my organizing work, teaching/learning, or artistic production: working with other people is what drives me. Even when I have to work on something independently, I am seeking feedback from people I respect and love at every stage.

Works and Projects

In Progress

Right now I’m running a foundations program at UMass Dartmouth. I’m advising around a hundred and twenty 17 and 18-year-olds in a given year, as well as teaching a seminar with all of them. I’m trying to take a traditional model of art education Foundation and update it with theoretical and social practices. The traditional foundations model that has ossified in schools around the world is to teach basic skills first, before later introducing ideas to use them towards. This is upside down and sets students up to have a “mastery” notion of art, upholding things like hierarchy, individualism, and elitism.

In class, we often talk about collaboration as a kind of muscle that has purposely been allowed to atrophy over the course of students’ primary and secondary education, as they are made to compete against one another. All the grading and standardized testing has atomized them to the extent that they often hate working in groups! More than anything, this disenfranchises them. So in this program, we try to rehab that collective muscle. It’s not easy at first, but through exercise, it becomes fun and eventually empowering.

The more they train that muscle, the more ready they will be for the problems society will inevitably throw at them. Education focused on instructions breeds passivity and apathy. Education should be about looking at each other and figuring out solutions together.

In Retrospect

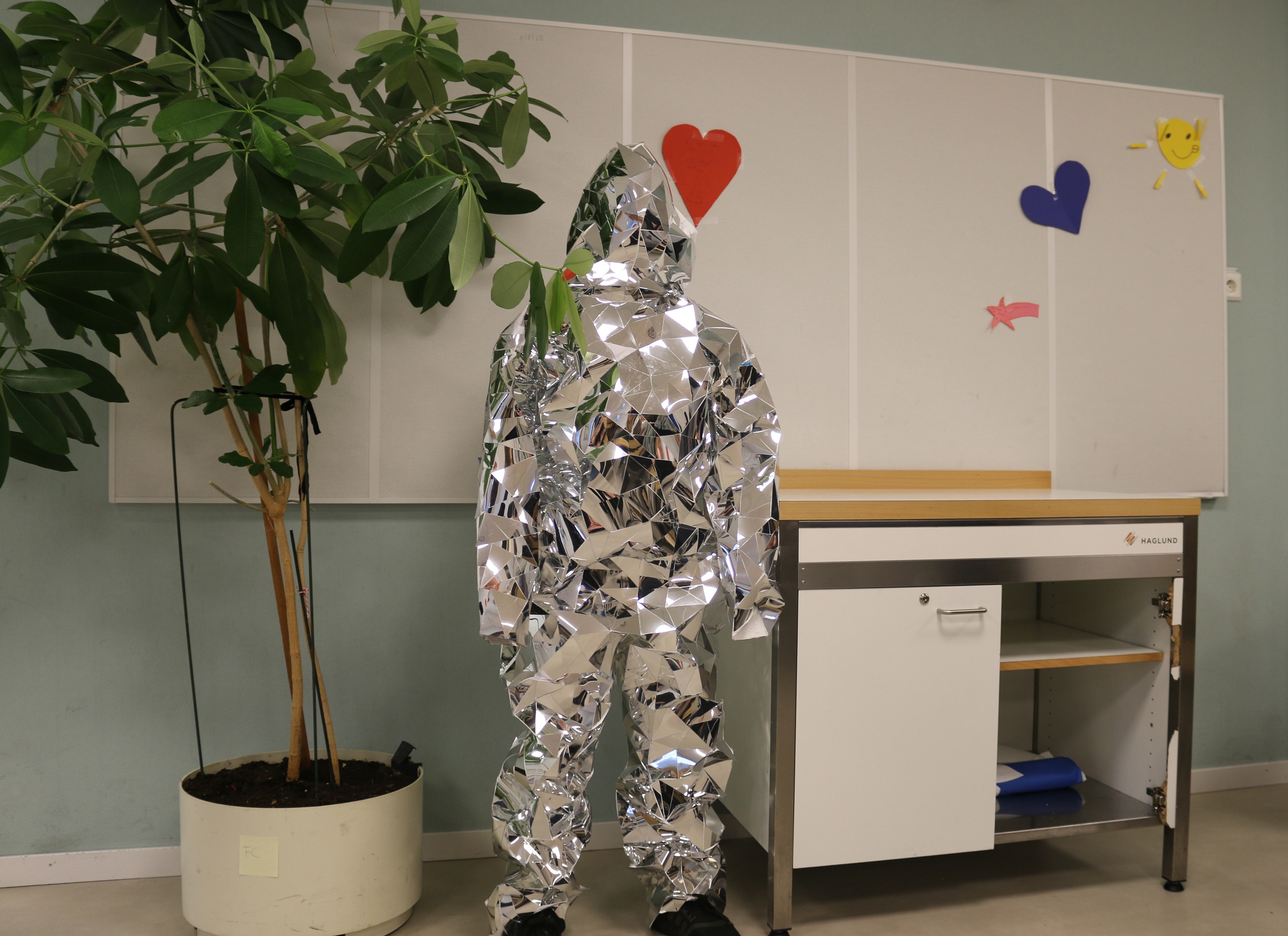

I’m still processing a project I did during the height of covid called Glorious Wound (2021). For it, I used French communist pedagogue, Célestin Freinet’s (1896-1966) pedagogical techniques to engage New York City Public School teachers in reflecting on shifting conceptions of the classroom during the covid era, the historical forces underlying education in the US, and visions for the future of education. The title came from the way Freinet described a lung injury he suffered that caused him to reimagine his pedagogy. On returning to teaching after being injured in World War I, Freinet could no longer project his voice to his students, so he decided to change his approach to teaching completely. Instead of the traditional unidirectional model of education, in which the teacher transmits information to the students from the front of the class, Freinet removed the rows of chairs and desks from his classroom, and installed a printing press in the center of the room. He then took his elementary school-aged students out into their communities–and together they researched the material conditions and lived experiences of the people they encountered. They then returned to the classroom, processed what they had experienced and committed it to print, before circulating the results to the community and beyond.

Inspired by this approach, in 2020 and 2021, I conducted interviews with public school educators from all over New York City. I asked them to write “notes” to people outside the school system. These notes riffed on the notes students pass around to each other in class behind their teacher's back.

The accounts the teachers gave continue to affect me. There is a general sense of disillusionment and hopelessness that has hit the profession. More teachers than ever are leaving their positions. I have been grappling with the feeling that as educators we are taught to think that we can save the world through what we teach in the classroom. We are told by culture that we have to fix the world through school. This is bullshit. We will never be able to compensate for the failures of society in the classroom alone. Having a real conversation about this will better allow us to work in ways that will bring about change rather than delay it by mitigating the damage of the current structure.

Contexts

Much of my work is centered on “childhood” and the ways different ideologies are apparent in the structures with which young people are surrounded. I often work to level or invert the power dynamic that exists between adults and young people. What this looks like varies considerably from one context to another, but young people everywhere are always talking. We just need to listen.

As an arts worker, I’m partially beholden to working within a structure that positions and rewards practitioners who come in from the outside and work for limited amounts of time and leave. This brings with it a large set of potential obstacles and pitfalls. I try to be as conscious of these as possible.

When developing a project, I often engage local pedagogues, parents, and young people, listening to what they have to say about the structures shaping their lives, and how they would like things to be different. To this end, I try to serve more as a vehicle to accelerate constructive processes that are already underway, rather than do something new and spectacular. To the extent that it’s possible, I want my presence to be an excuse for the things that are being left unsaid to be said, the things that should be done, to be done. This enables a situated process to emerge over time.