Techno-Poetics of Activism and Dissidence

06/24/2022

Felipe Rivas San Martín (Valdivia, Chile, 1982) is a visual artist, essayist, and sexual dissidence activist. His practice emerges from the crossings between queer activism, archive politics, decoloniality, and technology through mediums such as video performance, painting, installation, and cultural criticism, among others. His approach to art is inseparable from the spatiotemporal context, from his first experiences with the Colectivo Universitario de Disidencia Sexual (CUDS) to his current research proposing a queer critique of computer science and an algorithmic critique of queerness. From Santiago, Chile, he shares stories, references and methodologies for thinking and translating the transits between the analog and the digital.

Education

Schooling and Learning

I do not remember a clear origin of my interest in art, but I do recall certain moments that I consider influential as parts of a process. As a child, I really enjoyed drawing though some people in my family thought my drawings were "weird." My references were nature and television, and I drew those things as I saw them. I remember one drawing in particular: it was of the Flower Angel (Hana no Ko Lunlun), a Japanese anime series from the late 1970s. Angel was searching for the seven-color flower and, for that, she was given a magic tool (the flower pin), which activated its power upon reflecting the sunlight towards a flower, thus transforming Angel with an outfit and gifting her several professional abilities. My drawing depicted that supernatural moment of transformation. However, my relatives did not understand why, after drawing Angel so well with her brooch and dress and everything, I had "scribbled" all over the drawing. According to me, I was representing those magical waves that restored her vegetal power. Over time, I have noticed that many children’s drawings have those oblique-eye details that seem strange to the disciplined adult gaze.

A second moment was in high school, in Art class, which usually consisted in creating manual works. On one occasion, the teacher took us to a projection room and showed us slides with photographs of paintings. It was my first art history lesson. It was fascinating to discover that paintings were not simply the result of random creativity but that pictorial motifs, techniques, or even the use of certain color palettes could be associated with the political and social contexts in which they were produced.

Even so, I never thought of studying art or taking it to a professional level. For my family, that was unthinkable; the only suitable thing to do after high school was to study the three or four traditional courses. Partly because of that, I spent my first years of college in a scientific career and later in law school. But it was precisely at the university where I was able to approach a new aspect of art, without studying it yet. This experience was the activism developed with the Colectivo Universitario de Disidencia Sexual [University Collective of Sexual Dissidence – CUDS], in which I had the enormous good fortune to participate since its foundation, in 2002.

The CUDS was a very intense space of collective experimentation. We began by carrying out conventional left political activism because that was the reference we had, but that quickly intertwined with the incipient queer debates that resonated throughout Latin America, and also with the urgency to deploy different strategies from those used by traditional LGBT activism.

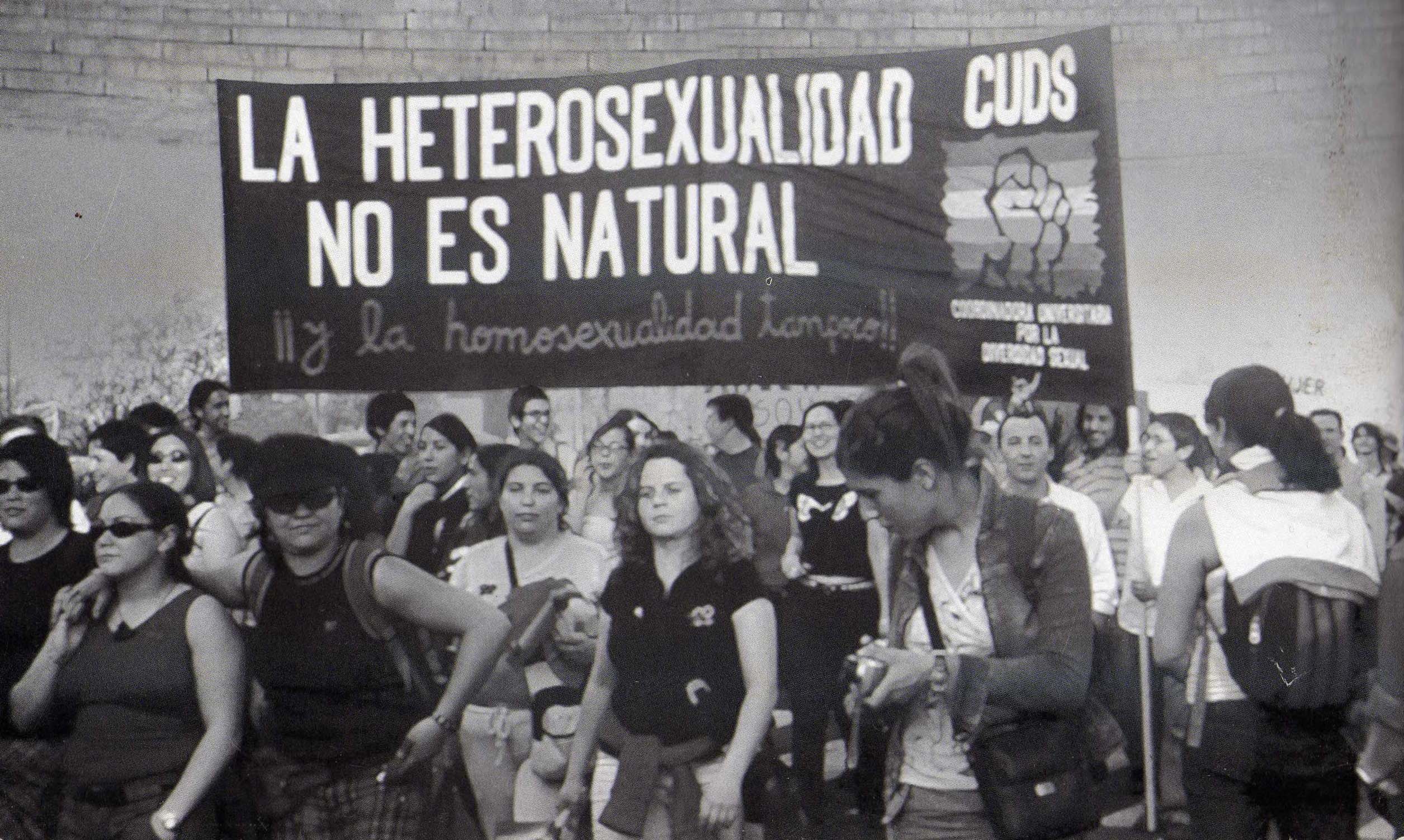

This unfolded in the performative actions that the collective began to make in public spaces. At first, we carried out public demonstrations in front of schools that discriminated against lesbian students. Later, in 2004, we made our first action in the Pride Parade, which consisted in carrying a very loud black banner with a disruptive phrase for the time: "HETEROSEXUALITY IS UNNATURAL." We deployed actions at specific points of the parade and marched in the opposite direction of the mobilization. This action, along with the demonstrations, eventually led to performances, video performances, and many controversial actions organized by CUDS, especially around abortion. These types of political strategies are characteristic of what came to be known in Chile as the "sexual dissidence" scene, in which CUDS took an active part, along with Hija de Perra and other groups.

Also in 2004, I met my partner, Alejandro, who is a painting restorer. Our house in downtown Santiago was for many years the epicenter of CUDS sex-dissident activism and all event after-parties. At the same time, our life together and his workshop space brought me extraordinarily closer to painting. Countless artworks went through there, and the relationship one has with the paintings in a restoration workshop is unique because the works are desacralized. Unlike the contemplative and normative relationship the spectator has with a painting in a museum, at the workshop, they are materially inspected: touched, smelled, and even licked. It is the best painting school you can have. Life with Alejandro taught me the love of painting, and it also showed me that living a professional life dedicated to art was possible.

Processes

Beginnings and Questions

Most of the time, project ideas arise from everyday, spontaneous experiences, from what I see on television or on the Internet, from a conversation, or from reflective and contemplative moments. Also, a previous abstract idea can be built, outlined, and realized through systematic research. At other times, new ideas emerge while researching a topic, which can be used to develop further projects that were not planned beforehand. Sometimes, ideas seem very rudimentary at first and become denser over time. Or they can appear at a given moment and not materialize until some time or even years later.

Besides from ideas, many projects spark from intuition. By "intuition" I mean a kind of feeling or startlement before something (a sort of proto-work or artistic project) that does not yet exist as such but arises as an uncertain possibility. For example, when you see an image in relation to another, it can trigger the feeling that there is something interesting there. You might look at something you have always seen, but suddenly you see it in a different way. I speak of images and objects because that is what we can most easily grasp, but these relationships can be established between more abstract elements, such as ideas, situations, concepts, sounds, processes, political events, colors, and so on.

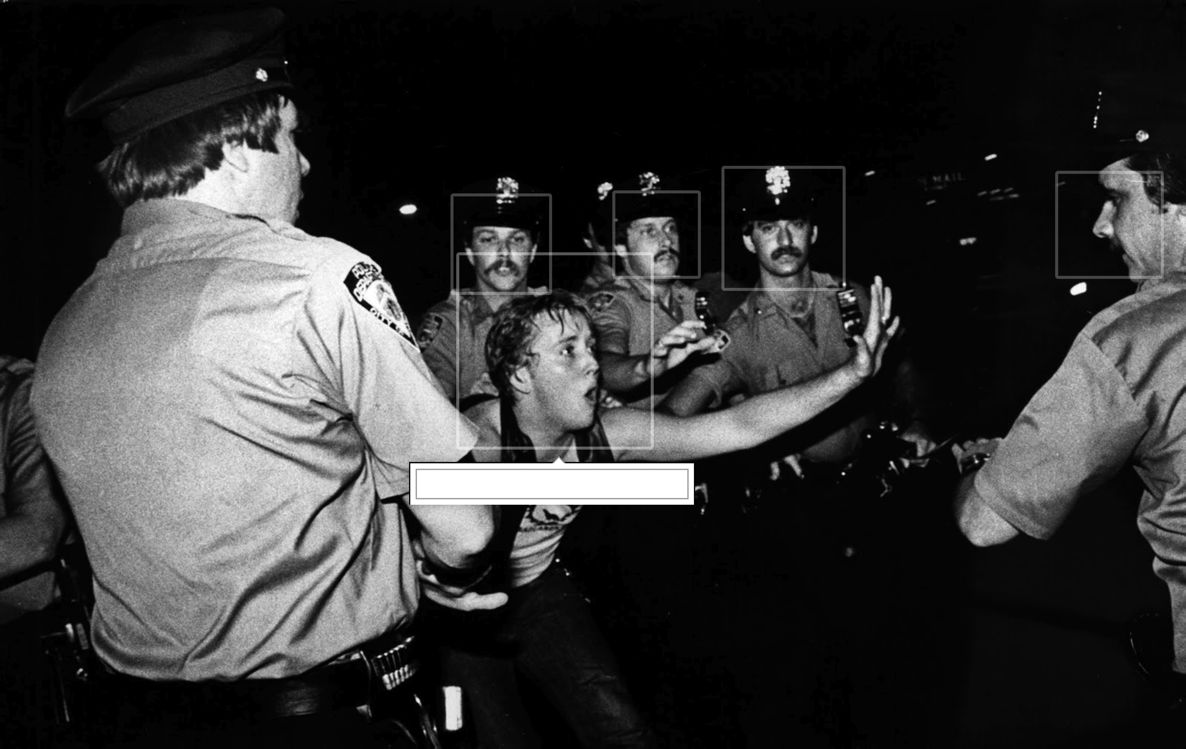

An example of such almost accidental processes is the Tag series, concerning biometric recognition. In 2013, I was browsing Facebook files when a photograph of a demonstrator participating in the heavy protests in Brazil, triggered by the increase in the price of public transportation, came up. The demonstrator in the street was holding up a sign in his arms that read: "We're off Facebook." Facebook and the street appeared as two radically opposed places. As I hovered over the photo, something happened that struck me as surprising: the biometric recognition sign appeared over the face of the protester. There was a human face there to which a name could be attached — an identity within the catalog or database (photos and profiles) of network users. A photograph that celebrated the street protest (concrete, material, effective), as opposed to network (virtual, immaterial, superfluous) participation, was circulating on the Facebook platform itself. This photograph of the anti-Facebook demonstrator had been subjected to the techniques and dynamics of the network.

The transition from analog to digital implies not only that the image has been digitized but also that it has become an "algorithmic" image, that is, subject to the technological dynamics of the control society. And all this was being made explicit by the tag sign, the label that interrupts — in a stylized and violent way — the unity and integrity of the photograph.

I decided to capture that suspended or unfinished instant between the recognition of a human presence and the identification of a particular subject. The result is a new image, intervened by the sign of biometric action. We know there is a human face, but as long as the box remains blank, there will be no definitive association between that face and an identity. It seems to me that there is a certain techno-poetics in the face recognition sign, which does not hold a single meaning — for example, data capitalism or digital surveillance — but differs and multiplies depending on the type of face-image to which it is associated. I have insistently continued to do this simple exercise with original photographs, paintings, drawings, and digital images.

Procedures and Strategies

Each project requires a particular way of working. I generally start with a vague impression or idea that undergoes different processes. Sometimes, these processes are very complex and can take quite a long time; they include conversations and theoretical and conceptual research. On many occasions, projects hibernate until something triggers their execution or materialization. Some paintings have taken me years to make, others I still don't consider to be completely finished and I take them up again in each exhibition.

Recently, I am also developing more intuitive projects, such as the prime numbers or the Zoom patchworks, which have evolved faster. The prime number paintings are a series I started in 2021, during the pandemic. They consist of medium-sized oil paintings on canvas that I understand as purely pictorial exercises. Initially, I seek visual references that are not so figurative; so far, I have used images of clouds, jellyfish, and cancer cells. Those images are the starting point of a pictorial execution that becomes detached from the motif-referent. At the end of this stage, I paint a prime number in white over the center of the image, in a size that is one-third of the height of the painting. Prime numbers are integers only divisable by the number 1 and themselves. So, in a way, it could be said that they are irreducible to themselves.

Projects

In Progress

I am currently finishing my doctoral thesis, where I propose a crossover between computer science and sex-dissident critique. The project is structured as a queer genealogy of computational algorithms. It aims to present a critical perspective of computer history and its alleged neutrality regarding sex-gender systems. My goal is to dismantle the sex-gender implications of the history of computer science through a queer analysis of a series of events throughout a non-systematic and non-sequential temporality that connects dissimilar moments and contexts. For example, the archaeology of the Andean quipus and their computational opacity as an effect of colonization, with the artificial intelligence games devised by Alan Turing in the 1950s. Or the beginning of user-profiles creation that led to the development of the Internet in the 1990s, along with recent artistic projects that propose "queer algorithms" based on the works of artists such as Zach Blas, micha cárdenas, and Evan Ifekoya.

In addition to configuring a queer critique of computer science, the doctoral project also performs the reverse exercise: a revision of certain stabilized topics within the queer discourse, in the light of the transformations imposed by the global deployment of computer technology. That is to say, an algorithmic critique of queerness. For example, the concept of ‘heteronormativity,’ proposed by queer academia in the United States in the early 1990s, must be reviewed both in its colonial effects and in its inability to identify the post-normative dynamics of algorithmic governmentality. To this end, the insights of Jacob Gaboury and Alexander Galloway, along with the works of Antoinette Rouvroy and Thomas Berns, have been very inspiring.

In Retrospect

A particularly significant project was Ideología [Ideology], a video performance I started in 2010, which had repercussions because of its implications between post-porn, my own homosexual political biography, and the Chilean left wing; all that condensed in a photograph of former president Salvador Allende. Of all my works, this is probably the one that has sparked the most episodes and controversies, such as the one that occurred during its screening at a festival in 2011, or the censorship episode effected by the Chilean Ministry of Culture in 2016, which involved a trial and got some media attention. The events that happen to the works, as well as the readings people make of them, get attached and end up becoming part of them. And one learns a lot from that because each comment, experience, or reading that a work provokes transforms it in some way, and you discover things about your own work that you had not seen before or that are entirely new. Because art is not a fixed thing — not even a painting or a sculpture is stable — it changes over time.

Another project I am very fond of is Interface Paintings, which I started in 2010. These are oil and acrylic paintings on canvas, whose motifs are screenshots of web platforms such as YouTube or Facebook. This project has involved a very complex work of production and creation, especially setting up the methodology to make them. It has required designing a digital-analogical translation system that spans from the screen capture to the finished painting on the canvas. The captured image must be decomposed into different elements that are understood and materialized as layers, almost emulating the layers of digital graphic design. This series has allowed me to approach the interface as a contemporary problem whose relationship with the subject-user is completely opposed to the one established by painting with the subject-spectator.

Contexts

It seems to me that, for artists, the context is always present, whether consciously or unconsciously. Even in the most abstract works, such abstraction can imply singularity, but I don’t believe it ever means a full autonomy of the work or artistic practice regarding its context. Even when art has declared its supposed formal or material autonomy, it is evident that the discourse was determined by a framework of discussions, evolutions, and reflections concerning that time.

Even when art has declared its supposed formal or material autonomy, it is evident that the discourse was determined by a framework of discussions, evolutions, and reflections concerning that time.This is evident in many of my works since several projects are closely, and even literally, related to sexual or colonial power systems of contextual nature, in the sense that they are reconfigured according to the space-time axes.

For example, this is the case of the video performance Diga queer con la lengua afuera [Say Queer with Your Tongue Out], which exposes the conflict of a language that is also a body while enunciating queerness in our territory of Abya Yala1. Even in less literal projects that at first might seem very abstract or disconnected from the context, such as the Queer Codes, I believe that my proposal makes a singular appropriation of the technological device, perverting its technical hegemony and provoking unexpected outcomes by contaminating the geometric abstraction of QR codes with the agitated codes of South American sexual dissidence or the Latin American political memory.