Miguel Braceli:On previous occasions, you have said that modern educational institutions follow a "linear logic," but we know that this is not the only logic that exists. How was the transmission of knowledge in the ancestral indigenous cultures of the Andes? Is there something similar to reason and method in their thinking structure?

A Precarious Education in the Creative Sense

03/01/2022

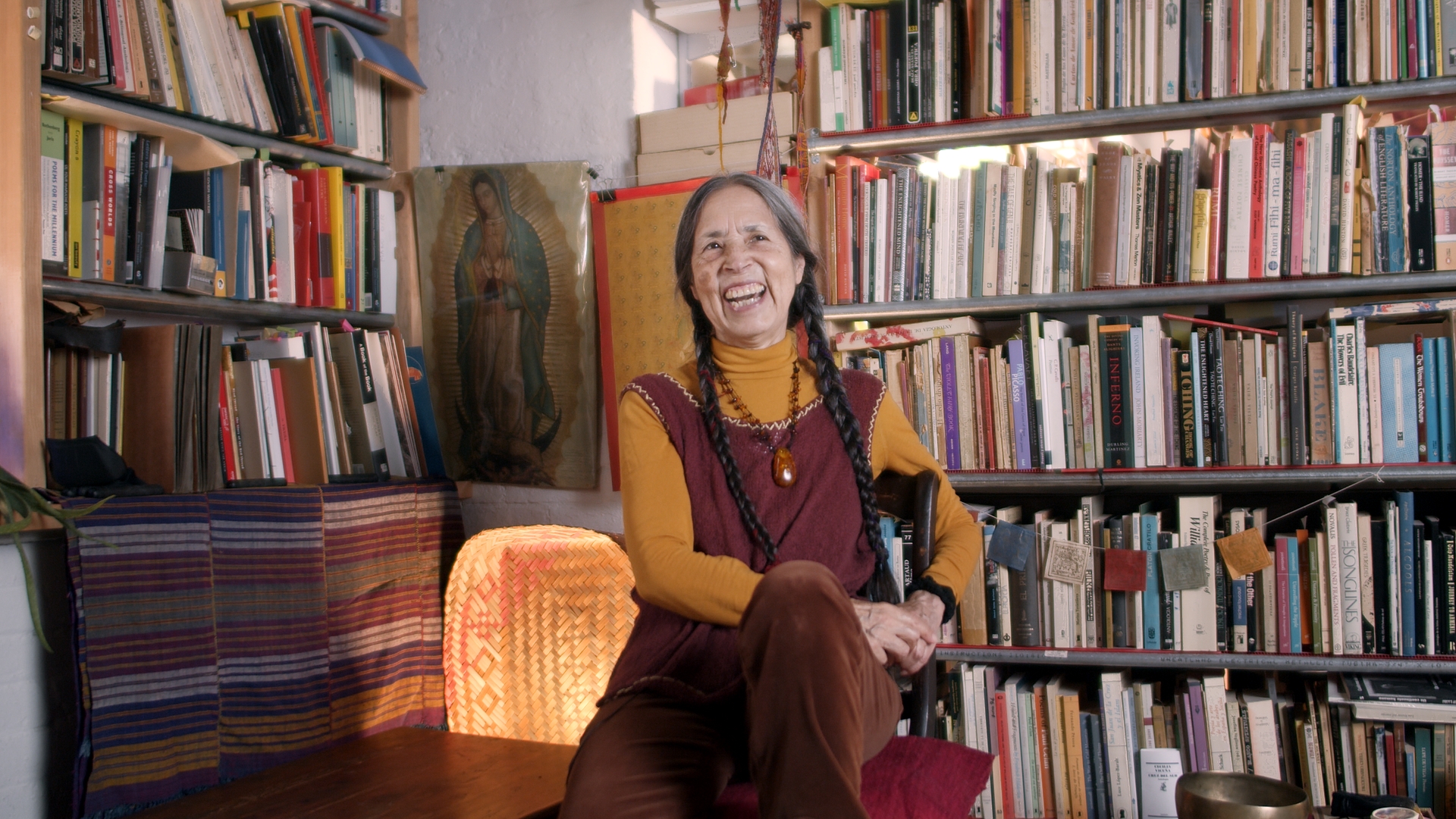

with Cecilia Vicuña

Miguel Braceli talks to Cecilia Vicuña about the artist's pedagogical experiences, her decolonizing take on knowledge, her understanding of feminism linked to ecology, and the possibilities of precariousness in Latin America as a potential for creation.

Cecilia Vicuña (Santiago, Chile, 1948) is a visual artist and poet who has explored issues related to nature, ancestral knowledge, and feminism throughout her extensive career. Based in New York City (USA), Vicuña preserves and shares deep wisdom about her indigenous roots, as well as experiences gathered through nomadic travels around the world, in which the knowledge acquired takes on intangible, "virtual," and collective forms through speech and listening, weaving and ritual.

Cecilia Vicuña: Yes, there is a form of logical thinking. But it is an indigenous logic, which is much more precise, more diligent—both in linguistic and philosophical terms—than Western logic. On the other hand, of course, there are many other forms of memory: the memory of the earth, the memory of water, the memory of beings that live beyond death. All of this is part of indigenous knowledge, a knowledge shaped through interaction.

It is very interesting that quantum physics is now beginning to admit that the only reality is the reality of interaction (that is an indigenous thought). An interaction in which forces collaborate, counteract, and readjust each other on a continuous basis. So that makes these different forms of logic and different forms of memory to be always in motion, to be always creating realities—whether in contraposition or in collaboration. It is not either one or the other, it is one and the other. That is the most interesting part and it is one of the reasons why it has always fascinated me: because one dimension does not exclude the others but considers them, includes them. Whether it is on the edge, in the presence of what is felt without being fully present as absence, as semi-absence and semi-presence. In other words, there is an infinitely rich range of potential perceptions and interactions.

It is well known that, throughout history, much knowledge has been forbidden by certain hegemonic power structures. In the case of European colonization, endless traditional and ancestral knowledge of the Americas was erased, stigmatized, and then lost within a colonized collective memory. This is the case of quipus, indigenous languages, and many other themes that are present in your oeuvre. You recover memories and knowledge in your work, but do you consider such actions as an educational act?

I can tell you that my interest in education is trauma. The trauma of the erasure, the trauma of the violence with which this knowledge was erased. When I was a little girl, they took me to an elementary school in Santiago. There was the first shock of what colonized education does to a child. I felt the violence of the school dogma in which the child has to sit and obey. But what did I do? I ran away from the classroom and left. That is the origin of my school: knowing as a child that there was violence there, an imposition. And I believe that rebelling against that imposition has formed many diverse schools, the most important alternative schools in the Americas throughout time, from the very beginning.

So this origin of trauma, of violence — it could be called epistemological or ontological violence, violence against the being of knowledge because knowledge is a way of being.

How do knowledge transmission processes take place through the quipu?1

All my work with the quipu and the other forms of knowledge that exist in my work, in writing and art, comes from a feeling that what I was was no good. Everything I thought, dreamed, and did was something that had no place in Chilean culture at that time, and that gave me strength and gave meaning to my work.

When I found out the quipu existed, I was a teenager, and it was not that I was interested in the quipu but rather it was as if the quipu, that universe, adopted me. I immediately felt it as an absence, as a lack. My first quipu was virtual, created in thought, and it was called “el Quipu que no recuerda nada” [the Quipu that remembers nothing] — that is to say, the record of the erasure, of that violence.

In current times, what knowledge do you consider forbidden? What areas of knowledge are still colonized?

Absolutely all of them. Where is there an uncolonized area? Within art, poetry, language, architecture, within some philosophical thinking, but not all of it. Decolonizing thinkers are not a majority yet, there is one here and one there but they exist, especially now that there are new generations of indigenous mestizos. For that liberating, decolonizing thinker exists—the way I see it—from the very moment of the conquest and the colony.

Indeed, among the areas you mention, in architecture, we can tangibly see the effects of colonization. You told me earlier that you studied architecture and that you even wrote about this topic. Could you tell us more about this?

When I finished high school and had to choose a career, I said to myself, "obviously, I have to study architecture" (even though I was already a poet and already knew I was an artist, but it did not seem to me that neither poetry nor art had to be learned or studied). But architecture was different. I went to a school of architecture because I thought it was the art that integrated all the arts, operating in the transformation of society and creating other realities, new ways of relating.

How did I think it and name it at that time? Through the precarious. My precarious works. I made my first precarious installation in the transition from high school to architecture school. I was 17 years old when I created a small city out of litter on the beach for the sea to erase. I recall that it was a project of remembering what an ancient civilization could have been like or what a new civilization could be like. Architecture was all that for me.

That text I wrote, titled “Educación por la Arquitectura” [Education through Architecture], is a contemplation on what a building teaches someone who enters the building. It was from the perspective of a little girl, so wherever there was a well or an architrave, I asked myself what was that architrave communicating to the body?

You also mentioned that you were very quickly disappointed in architecture education at the time but that you have a different take on it now.

I am sure that there have been many schools of architecture in Latin America that would have been perfect for what I imagined architecture could be. But I chose precisely one in which they did not think like that, so I lasted very little, only a few months. I realized then that I had to go to an art school, just to be given the space to think and be as I was and not be forced to follow a program. Later, over the years, I found out that around the same time I finished high school and began to make my precarious work, the School of Architecture of the Catholic University of Valparaíso began to function and Open City [Ciudad Abierta] was founded. It is interesting that I invented the precarious less than 4 kilometers away from there, but neither Open City knew about the precarious nor did I know that it existed.

The Open City of Amereida (as the poem goes) aimed to find the meaning of the American continent. There was a profound interest in the local and on the site, developing formative practices that triggered and uncovered a territory of their own. There is something about the ephemeral and the body that you have mentioned about learning in architecture. How can this knowledge be transferred to education? How can the contributions of the Open City be taken up again?

I am not one to say because I was not a participant of the Open City, although in some way we have had some very wonderful encounters. But I can tell you that the precarious is, somehow, already from its conception, a form that unites and merges the potential of architecture and the city but in the daily life of the city or the countryside. There is a sense that the poetic and the architectural exist in precariousness. However, even though they practiced it, Open City did not create the concept of the precarious. I was the one who invented the concept of precarious art. That is why I find that there is such a deep confluence, but Chilean society has not been able to recognize or grasp that because the precarious has no category in the face of architecture. So that devaluation of the precarious is just beginning to be transformed through the fact that now global culture has started saying that life itself is becoming precarious. We still need to bring all these currents together, so that they really have the transformative effect of education and architecture in general, and are not just islands of creativity.

In Latin America, precariousness is also a reality we cannot escape, but it becomes a stimulus for creativity as well. What could be its relationship with our educational systems?

What does precariousness consist of? In that everything disappears. That is the core of creation in precarious art. It is an art that is aware of its own disappearance. So, how does that relate to Latin American popular cultures? In Latin American popular culture, all the favelas, all the cayapa settlements, are all forms of precarious architecture and creation. But has there been a school that gives true meaning and value to that precarious way of survival and coexistence of Latin American indigenous and mestizo culture? This philosophical leap has not yet been taken. Although it already exists and has always existed. It is part of colonization. How could this be integrated into education? There has to be a philosophical and historical perspective of the meaning of the precarious.

Since the Spaniards and the Portuguese arrived in America, they came to destroy the worldview and order in which all the various balances at play flowed and swayed. This precarization is experienced as a violence, on the one hand, and on the other hand, as a reparation, as a healing, as finding a way out against all odds. I believe that, if this endless search of precarious creation — which is happening all the time — is given value, it can transform education. If, instead of teaching only fixed contents, education also includes contents that are created in/by the moment.

There must be in education a system that includes improvisation, that makes room for error, failure, search, and exploration. Thus, education would become precarious in the creative sense and not precarious in the sense of not having funds. Because now if you say 'precarious' it means that you have no money, but money is not a fundamental factor in education or in any other value. The fundamental factor is how one sees the situation. If you see it as a loss, that is one thing. But if you see it as the possibility of creating another variant, it changes everything.

Since you touch on this subject, it opens another reflection as well: In the North, they have been interested in these issues from theory but we have come to these issues from experience and reality. They are completely different approaches.

What you say is very interesting and it is very rarely discussed in the way we are discussing it. Because what happens is that precarization as a topic arises in academia in the northern hemisphere. From there, it contaminates the academia of the southern hemisphere. And this is very interesting as a trajectory of the concept of precarization, because before that, from Latin America we had always talked about it as a lack, not as a power.

Another reality that defines our contexts is political instability. Your artistic work began before and very close to the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, in the mid-1960s, and all of Latin America was by then a politically convulsed territory. How did this affect your standing as an artist?

To be a creature of the sixties was something fundamental for me. Because the sixties was a moment of immense creative potential in Latin America. You see that the revolutions that took place in Cuba, Brazil, and Chile were in fact possible, I mean, there was a whole period of a quest for the transformation of social structures. That transformation was happening — as it always does — in art and poetry from before. That is to say, the disintegration of the colonized languages had already begun. That investigation into the given structures as a structure to be disrupted, dismantled, and reassembled was already in art and poetry, and somehow precedes the idea behind revolutions that societies must also be transformed and readjusted, so that there is dignity, justice, and balance between all parties at play.

How did this confluence between the social revolution and the poetic revolution affect my work? In a total, radical, and absolute way. I perceived poetic invention as part of that revolution, not as two separate things. I never had the idea that politics and poetry go on different roads.

By that moment in the 20th century, we also find a high point of the feminist movement. I understand that, for some time, your "narratives" were not accepted by the feminist militants of that period. In a way, your language has always been steps ahead of your time. How is your understanding of feminism today and how was it at that time?

Yes, it is very true that the feminism that I came across first—I mean, I felt a feminist from the moment I knew that the word 'feminism' existed, which was when I was a little girl. Not because I read any books but because it started appearing in magazines. When I saw it, I said to myself, "of course, I'm a feminist too." But when I started to come across the theorization of feminism, it was a completely Eurocentric theorization. And for that same reason, my generational fellows practiced feminism as theorized from Eurocentrism. That is why I was never perceived as a feminist.

But what has happened is that a new feminism has arrived, one that is lived starting from little girls. For them, there is no Eurocentric theory or anything like that anymore. They feel for themselves, from their own experience. They are empowered to be themselves. It is a completely different kind of feminism, which totally connects to the girl I was in the sixties and seventies. Because we have this common desire to discover what it is that we are, beyond definitions. That is a powerful desire as a transformative force, and I see it in action now. I find the radicalization that exists now dazzling, and I find that it connects with what animated the spirit of profound rebellion of Latin American poetry and art from the beginning.

You have talked about how hopeful you feel for activist manifestations such as those of the feminist collectives in Chile, the decolonial movements, and other groups that seek to generate an impact on the conscience of those who witness their actions and images. They are situations that point out and denounce particular problems but they also educate a collective. What core values can be extracted from these manifestations, to understand the change they exert on the conscience of citizens?

The wonderful thing about all these manifestations is that they are recovering a way of acting and being in collective, which is something inherited from the mestizo indigenous culture. In the same way that I have, many artists have begun to recover collective work in the form of unguided creation, genuinely created by the collective.

I believe that the sum of all those projects, however invisible they may have been, has created a breeding ground from which these current collectives have emerged. So there is continuity, there is a lineage of passion for the idea that working together creates realities that have the capacity to affect society as a whole. That is really the profound triumph of indigenous culture against colonization, which individualizes, separates, and tries to say that "it is this against that." And it is not so. Reality is something much more complex, and it is participatory.

So, does all this interest in collective practices in Latin America find its roots in indigenous traditions?

Of course, and that is beginning to be acknowledged. Not all Latin American artists have had the possibility to experience and feel what that really means, because the discrimination and separation of the mestizo culture of cities from the indigenous culture have been quite violent, traditionally very violent. For example, you know that the vast majority of Latin Americans are mestizos and yet very few of us, still a minority, choose to feel from both sides. And, moreover, to give a space of wisdom to the indigenous.

I believe that in Latin America there still exists the possibility—as these collectives are proving—of reorienting and transforming culture towards another state of consciousness.

You just mentioned a recurring idea: transforming realities. Is that a property of art or of education?

It is naturally a virtue of both. There is no need to make an effort to make it a property of both. That is, the effort of education itself as potential is different from education as it is conceptualized now. Education is still conceptualized as something inculcated. Eventually, there will come a time when education is a process that is happening mutually, as Paulo Freire Paulo Freire used to say. He formulated it in a completely futuring way.

About this future that we have built, you often speak of the failure of humanity as a species, regarding the destruction not only of cultures but also of their habitats. Is this also a failure of education?

I believe it is true that powers continue to fail. All agreements are null and void and are minimal in relation to what is needed. In other words, the possibility of extinction is still dominant. As long as there is no transformation of the political and economic order, we are going straight towards destruction. But this feeling of hope that you sense in me is precisely because of the young people. I know that there are artists and educators generating these forms of effective love, love with rigor. As long as that exists, there will be at least a tiny glimmer of hope.