Art as a Form of Knowledge. Processes of Participation and Active Reflection in the Works of Lea Lublin and Cecilia Vicuña

03/10/2022

This "provocation to thought" and the action that consequently occurs is something that we will see ahead in a selection of works by Cecilia Vicuña and Lea Lublin (...) How did the searches of these artists materialize around art and education? How did they dismantle the established ways of seeing? What is the role of the body and intuition in their works?

The artworks produced between the 1960s and 1970s went through radical changes in their way of engaging with audiences. The dematerialization of the art object–a term introduced by Lucy Lippard in 19681–was accompanied by increased interest on the part of the artists in engaging with the social and political reality of their contexts and, consequently, with that of their spectators. Their up-until-now passive and contemplative role begins to be activated employing experiences, processes, and situations where art and life often converge, questioning the parameters of what is considered "art." In several articles written between 1968 and 1971, the Brazilian critic Frederico Morais gives an account of this new role of the artist as a "proposer" or a "creator of tensions," and that of the spectator as "co-creator."2 The body as "engine of the work" and the ludic character of art gain prominence to rethink the role of pedagogy in artistic practices and vice versa. Its integration generates alternative forms of knowledge, in an attempt to blur the categories or disciplines that usually categorize knowledge. On the other hand, public space and locations outside the art world, such as factories and public parks began to be the main stage of many of these propositions.

Meanwhile, several Latin American countries went through military dictatorships which increased censorship and repression in the cultural field during this time, forcing the migration of artists and writers to other countries. In the case of Chile, the socialist government of Salvador Allende was overthrown by General Augusto Pinochet in 1973, only two years after it began. In Argentina, the dictatorship of General Juan Carlos Onganía, starting in 1966, would mark the beginning of a long succession of military governments that ended in 1983. Paris and London were two of the cities that hosted the largest number of exiled artists in those years, including Lea Lublin and Cecilia Vicuña, respectively. In addition, the student protests of 1968 in Paris had vast repercussions on the European cultural, social, and artistic context, as well as in Latin America. The protests carried out by students and teachers resonated in the works of both artists, as did the movements of the second feminist wave. Regarding this, Griselda Pollock comments that feminism presented a challenge on the curatorial side but also for visitors, since it implied a reorientation of art as consumption or entertainment "to art as the provocation to thought through affect, humour, intelligence and creative materiality and participation."3

This "provocation to thought" and the action that consequently occurs is something that we will see ahead in a selection of works by Cecilia Vicuña (1948) and Lea Lublin (1929-1999). Their projects and writings serve to reflect on the role of art in society and its full integration with other fields of knowledge in the late 60s and throughout the 70s. Both artists, each in their own way and from specific contexts, sought to promote an active and conscious reflection in the viewer, encouraging a ludic and critical approach at the same time. Some of the guiding for this text are: How did the searches of these artists materialize around art and education? How did they dismantle the established ways of seeing? What is the role of the body and intuition in their works? How was their approach to art crossed by language and poetry in each case? What role did public space play in their works?

The selection of their projects does not come as a result of a close contact or collaboration between the two of them, but rather as an attempt to fathom how their works expanded the dialogue of the artistic practice to other disciplines and media, trying to deconstruct our ingrained ways of seeing. This arises from how each of them rethinks the role of art in everyday life, highlighting the conditionings produced by established and socially endorsed education systems. The artistic experience proposed by their works is capable of triggering processes of (self-)knowledge and awareness in the individual, appealing to language, imagination and poetry as the core components of this epistemological transformation. On the other hand, we will retrieve their ideas regarding the role and voice of the audience, which reflects in their interest in the collective and participatory nature of some of their works. Finally, it is interesting to see how the work of both artists—especially during this period—also presents a shared interest in approaching culture and nature in a dialogical way, along with a feminist standing in their writings and works.

Altogether, we can say with Luis Camnitzer that the works of Lublin and Vicuña account for this convergence between art, poetry, politics, and education in Latin America during these decades.4 Setting out from their specific contexts of action and dialogues with their contemporaries, we will attempt to trace certain pedagogical elements that are present in their practices with the aim to encourage autonomous, creative, and critical thinking at the same time. In drawing these connections, we will consider their ideas around participation, the importance of process and experience, the body as a platform for rational, emotional, and intuitive knowledge, and the role of the spoken and written word in their works as starting points. The goal is not to lay out a totalizing and chronological view of their projects but to deepen the understanding of how they worked these concepts intending to generate a transformation—in the case of Lublin—or a revolution—in the case of Vicuña—from their artistic practices.

Links Between Art and Pedagogy

The cultural and political horizon of the 1960s gave rise to some of the first crossings between the visual arts and pedagogy, which derived from the inclusion and experimentation with other disciplines such as philosophy, biology and sociology, among many others. In the United States, Allan Kaprow took his happenings in new directions, emphasizing interpersonal communication and its role in education and leisure. The reading of authors such as the sociologist Erving Goffman and the biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy oriented this process which, together with his artistic experiments in photography, led him to develop an avant-garde artistic program at the University of Berkeley,5 together with educator Herbert R. Kohl. Kaprow's practice came close to social psychology, given its focus on the gestures of communication, encounter, and exchange. In Europe, his research resonated with that of French artist Robert Filliou, who wrote in 1970 about performance as an art of learning and teaching in collaboration with colleagues such as John Cage and Joseph Beuys.6 In it, Filliou defends the role of intuition, calls on adults to learn from children in their creative use of leisure and asserts that freedom entails a lack of discipline, idleness, spontaneity, fantasy and improvisation.

As we will see, these psychosocial aspects and interdisciplinary approaches also constitute a fundamental part of the projects that Lea Lublin developed in Argentina and Paris. Born in Poland, Lublin emigrated to Argentina with her parents when she was a child. After completing her studies as a visual artist at the Academy of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires in 1949, she traveled to Europe in 1950 and settled in Paris a year later. Although she stayed in touch with Buenos Aires during the 60s, she settled in Paris definitively in 1972. Unlike Cecilia Vicuña, Lublin was part of an established art scene and was in close contact with the main figures of the art circuit of the time—such as the writer Philippe Sollers and the critic Marcelin Pleynet. This also shows in the theoretical depth of her writings, where the artist unfolds her interest in dismantling the image and its processes of creation as well as interpretation on the part of the audience. At the same time, constantly traveling between Paris and Buenos Aires allowed her to get in touch with artists and intellectuals working in both capitals, something that reflects in the questions and formats she chooses at this point in her career.

In Paris, the research of Beuys and Filliou concerning the pedagogical component coexisted with those of other artists and collectives who had been developing their work from a critical perspective towards the consumer society, such as the International Situacioniste. This group pursued—in more radically political and anti-capitalist terms—a transformation of life through direct interventions in everyday life, stepping into public space, and driving drifts through the city. In Paris was also active the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (Visual Arts Research Group - GRAV),7 who in their manifesto "Assez de mystifications" [Enough of Mystifications] emphasize their special interest in the viewer: "The public is a million miles away from artistic events, even so-called avant-garde ones. If there is any social concern in art today, it must take one very social reality into account: the viewer."8

The art scene taking place in the big cities during the 60s and 70s, coining new terms such as 'actions,' 'happenings,' and 'performances,' developed in tandem with the incorporation of new technologies in artistic practices and greater integration of it with other disciplines. However, these scenes translated in different ways in Buenos Aires and Santiago de Chile.

In Buenos Aires, the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella (ITDT), directed by Jorge Romero Brest, was the epicenter of the avant-garde movements between 1965 and 1970. After being shut down by the government of Onganía, the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC - Center of Art and Communication) took its place. There, the critic and curator Jorge Glusberg would develop his ideas around Arte de Sistemas [Systems Art], made up of "processes and experiences which concern the artists who are working in this last third of the twentieth century. Within this term, I include art as idea, political art, ecological art, propositional art or cybernetic art."9 Despite her long stays in Paris, Lublin always maintained contact with both institutions. The Instituto Di Tella sponsored her Terranautas project in 1969, and together with the CAYC group, she showed her work in Colombia and the United States.

Although these spaces encompassed a large part of the mainstream art and avant-garde theory of the time, other projects also took place during these years, which accounted for the need of artists to position themselves in the face of the growing repression and violence produced by the dictatorship. In regard to this, Camnitzer affirms that "the new project for the Argentinean artists became the revision of art so as to engage with issues of social classes."10 This line of projects accounted for a more radical and non-conformist political position, where the public played an essential role along with the communication strategies of the work. Projects such as Tucumán Arde (Confederación General del Trabajo - CGT, Rosario and Buenos Aires, 1968); El Baño by Roberto Plate in Experiencias 68 (ITDT, 1968); or El Encierro by Graciela Carnevale (Ciclo Experimental de Arte, Rosario, 1968), had a certain resonance in the works developed by Lublin in Santa Fe and Buenos Aires in 1969.

On the other hand, the cultural climate that preceded the election of the socialist president Salvador Allende in Chile in 1971, accounted for the repercussions of the French May of '68. At that time, Cecilia Vicuña was part of Tribu NO and was beginning to experiment with the links between body, space, gender, and fiber. Born into a family of artists and writers, she studied at the School of Fine Arts in Santiago, where she lived until 1972. That year, she moved to London with a scholarship for studying at the Slade School of Fine Arts until 1975. When her visa expired, she traveled to Bogotá, where she lived until 1980.

In 1973, Vicuña made a performative reading at the Institute for Contemporary Art in London (ICA), where she gave an account of the social and cultural climate that preceded Allende's election, along with the changes she witnessed after the revolution of '68.11 Student struggles in Paris led to reforms in art schools in Santiago, raising awareness of political movements and a surge of women artists. In turn, the democratization of art manifested in a new group called 'Arte para todos' [Art for all], which showed art in the streets and brought performances, readings, theater, and film screenings to remote places and smaller towns. Each neighborhood had its own brigade, which created murals with poetry, messages linked to socialism, and paintings. Lublin also took part in this cultural scene, since she was presenting Cultura: Dentro y fuera del museo [Culture: Inside and Outside the Museum] at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago, Chile, at the time. In the musical sphere, Vicuña talks about the "new Chilean song," resulting from the integration of folk music, American protest songs, indigenous traditions, and Latin American rhythms.

Vicuña also mentions Violeta Parra, whose portrait she painted in 1973, and the role of payadores12 as key figures in the transmission of oral knowledge. Another issue she addresses is the resistance of the Mapuche people and the seizing of factories by their workers—something that will be dismantled with the neoliberal policy of Augusto Pinochet. According to Julia Bryan-Wilson, the mention of these facts is not a minor detail: it reveals her knowledge of the struggles that went on in the textile factories controlled by their workers during the Allende era. She also alludes to her awareness, already at the beginning of the 70s, about the consequences of making textile-based objects, since these functioned as a space of contestation on the bodies of workers.13

In this scenario, we must also consider the presence of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, who was exiled in Chile between 1964 and 1969, and who introduced new ideas regarding pedagogy and literacy of the working class. Invited by the Christian Democratic government of Eduardo Frei Montalva, Freire continues there the literacy campaign he had begun in Brazil and which had been interrupted by his imprisonment after the coup d'état. Freire favored a dialogic education, promoting processes that raised awareness among the peasantry during the agrarian reform. Very soon, the process of popular literacy grew in such a way that educators belonging to other organizations, such as the Student Federation of Chile and the Single Central Organization of Workers of Chile (CUT),14 were summoned. In this climate, art workshops for the workers arise inside factories, aiming to generate values of solidarity and provide tools for the development of their own thinking: "To consolidate the revolutionary process, we must create a strong cultural movement. We have to shift people's minds and consciousness. A new thinking must replace the reactionary ideology.15 Toward 1970, the Teatro Nuevo Popular [New Popular Theatre] was also conformed as part of the pedagogical and cultural program of the Central Unica de Trabajadores [Single Central Organization of Workers], which Cecilia knew through her cousin.

According to Carla Macchiavello, Vicuña did not meet Freire during his stay in the country nor was she familiar with his methodology.16 However, as we saw in Vicuña’s 1973 reading, the ideas of radical pedagogies that emerged in Latin America—such as Liberation Theology and Popular Education—were experienced through different proposals in everyday contexts. Upon beginning her formal studies in pedagogy at the University of Chile in 1966, Vicuña created her first precarious objects and experimented with her first palabrarmas [wordweapons]. At first, these arise by playing with the syllables of a certain word, breaking them apart and rearranging its parts to give way to new meanings and articulations. Both the end result and the creative process leading to it are important. For Macchiavello, the process of taking words apart in order to create other meanings is formally and ideologically linked to Freire's teachings and methodologies. The author recalls the method implemented by the latter for "awakening consciousness” based "on a battery of 'generating words' related to the participants’ daily lives, which was used for stimulating conversations about their social, economic, and political situation.17 The goal was not only teaching to read and write but to encourage the participants to explore their own creative universe and potential for change, encouraging a critical perspective to free the oppressed from their subjugating forces.

By 1974, as she was studying in London, Vicuña retrieves this creative process of palabrarmas and develops it further as a form of visual poetry that was politically and pedagogically committed to counter the Pinochet regime. In parallel, she helps found the coalition of artists, curators and writers called 'Artists for Democracy,' together with Guy Brett, John Dugger, and David Medalla. With collaboration from other colleagues, the words gained new textures when they were combined and intervened through collage. Together with John Dugger, for example, she made the banner Arte Emancipación / Participación [Art Emancipation / Participation], where both terms came out of the word 'art,' diverged in the middle, and came together again towards the end. In Pala abra [pala ‘shovel’ - abra ‘open’ – palabra ‘word’], both syllables are presented with the background drawing of a shovel, reinforcing the idea of inquiring into language. Regarding this, Lucy Lippard points out that dissecting a word not only accounts for its structure, it is also a way of exposing its internal metaphors,18 as Lea Lublin does in another realm with images and the history of painting.

Toward 1980, now living in Bogotá, Vicuña integrates words as portable objects that she uses in actions she carries out on the streets along with her friends. Visors, headbands, and translucent banners foreground the wordplay in their interaction with the city. Carla Macchiavello sees in these actions other ways to generate participation, by reconnecting people with the deep meaning of words and life itself through play in the urban space. The video documenting the activity Sol y dar y dad, una palabra bailada [Solidarity: To Give and Give Sun, a Danced Word] shows a group of children and adults playing and dancing with fragments of this word atop the city, creating a moment of interaction and physical reciprocity that transforms reality and the surrounding environment.

Towards an Active Reflection

The so-called 'participatory' art of those years was generally associated with a ludic interaction with the viewer that could range from the visual effects of kinetic art to propositions for happenings, actions and performative installations, where the viewer entered into unsettling and unexpected situations. The type of participation or engagement required by Vicuña's palabrarmas—and, as we will see ahead, also by Lublin’s installations—opted for another kind of exchange: in them, the ludic aspect was combined with elements that sought to generate a critical reflection in the spectator about the social, economic, and political context of the time.

Around 1969, Lublin traveled to Argentina to carry out the installation Terranautas [Terranauts] at the Instituto Di Tella, and Fluvio Subtunal [Sub-Tunnel Flow] in Santa Fe. In them converged many of the spatial, temporal, and social searches that Lublin had been describing since 1967 in her writings "Procesos a la imagen I, II y III" [Process to the Image I, II, III]. In these projects resonated traces of the GRAV, drifts of Situationism, and even happenings and actions of the sort carried out in previous years by colleagues such as Alberto Greco, Marta Minujín and Graciela Carnevale. However, Lublin’s installations sought to question—beyond the ludic aspect—the cultural conditionings affecting the elements of the knowledge system. Terranautas intended to "trigger action and thought in the viewer, who is an integral part of the work in a new relationship: LIFE_LANGUAGE = ART."19 Both projects were structured as sequences that visitors had to go through, moving from one area to another. These spatial sequences reflected the system of multiple connections between art and life that the artist meant to exalt. In these works, as in the ones she developed later, Lublin emphasized the process that viewers go through, giving an account of the shifts in perspective they can gain by choosing from where to position themselves—physically and intellectually.

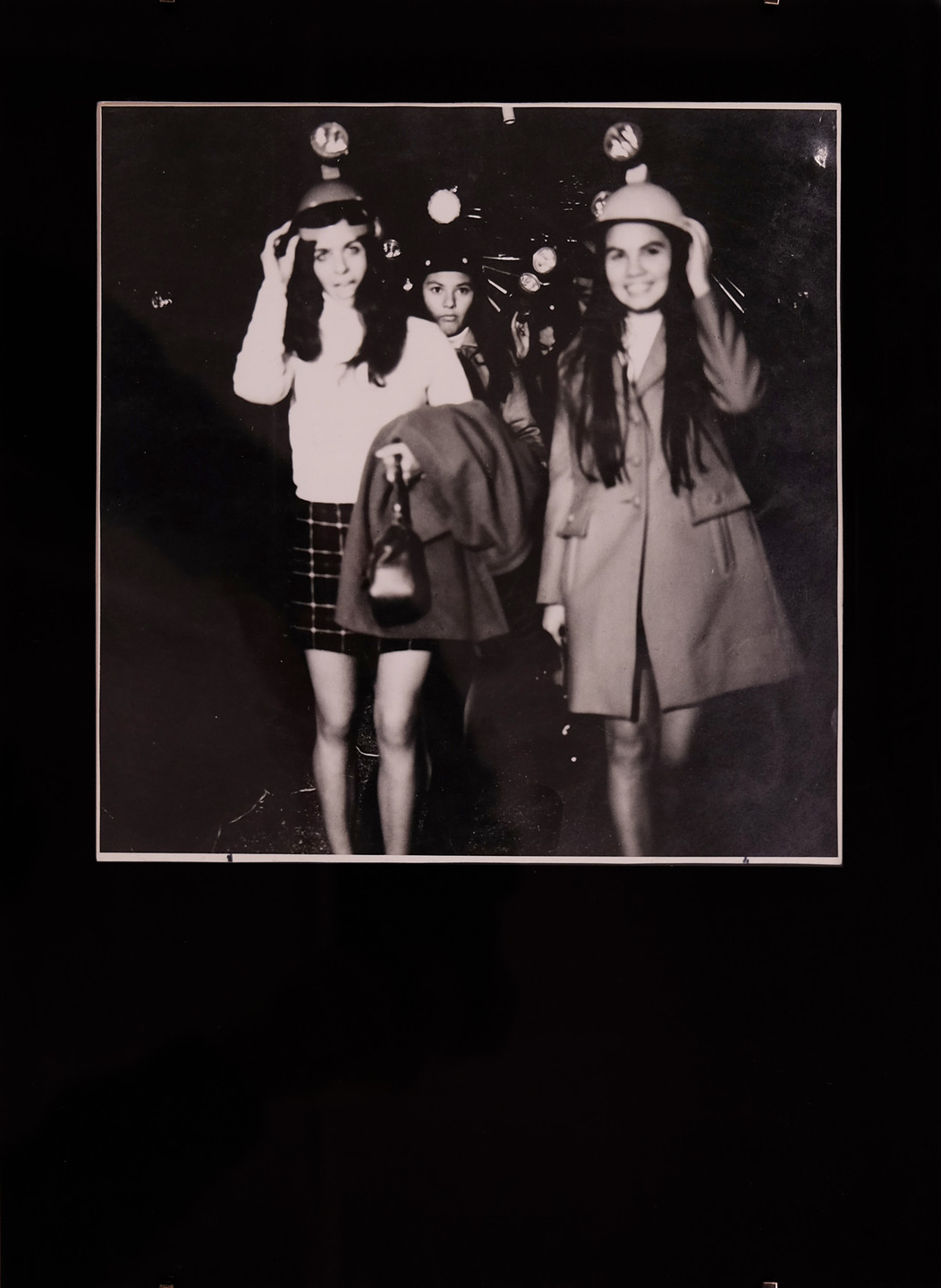

The title Terranautas arises from the landing of man on the Moon a few months before, inviting the public to rediscover all kinds of sensations and materials linked to planet Earth, such as earth, sand, chalk, and other plastic materials. In this labyrinth-shaped installation, the visitors had to walk barefoot through unlit areas, provided only with protective miner's helmets with flashlights. The inability to see breaks and reorganizes the way in which we connect to the environment, creating a disorientation that forces us to activate the other senses and move through space in a different way. This is something that Lublin had already been working on in her painting and that she would continue to do in her later works: to question the learned ways of seeing, which leads to producing a certain knowledge and order of the world. Along the path, visitors came across luminous signs with different messages: "Art will become life,” "Reflect and act,” “Think," "Choose and strike,” "Walk freely,” "Take off your clothes and think.” At the end of the itinerary, the "Room for Reflection" invited visitors to relax and take their time to process what they experienced. This invitation from the artist to an active reflection, which she would also develop in later works, gives an account of certain tools that continue to be encouraged in the artistic-pedagogical practices today.

The opposition between nature and technology continues to be present in Fluvio Subtunal, a multimedia installation carried out in 900 m2 warehouses in the city center of Santa Fe, on the occasion of the opening of the subfluvial tunnel that would link this province with Entre Ríos. Pierre Restany speaks of this installation as “an architecture of information,” proposing “a sociological demonstration, a systematic working of the structures of psycho-sensory communication.”20 The project invited visitors to a sensory walk in nine zones: ‘La Fuente’ [The Source], ‘Zona de los Vientos’ [Wind Zone], ‘Zona Teconológica’ [Technological Zone], ‘Zona de Producción’ [Production Zone], ‘Zona Sensorial’ [Sensorial Zone], ‘Zona de Descarga’ [Unloading Zone], ‘Fluvio Subtunal,’ ‘Zona de la Naturaleza’ [Nature Zone], and finally, the ‘Zona de la Participación Creadora’ [Zone of Creative Participation]. Each of them featured a particular atmosphere according to its theme. They were made of trampolines, translucent screens, inflatable tubes, and projections. Some areas presented fragments from the constructions of the tunnel, incorporating construction machinery, local products, and photographs of the workers projected on transparent plastic curtains that had to be traversed to access the Technological Zone.

The decision to place the projected images on mobile—not fixed—sheets results in the viewer being able to see or to go through the images in other ways. As Esther Ferrer argues, movement in these works occurs on other levels besides the physical.21 The intervention of the projected image on both sides of the plastic is another strategy—together with darkness—to displace the reading habits, breaking the linear interpretation and giving rise to multiple connections. Finally, although the nature of the installation was playful and festive, Stephanie Weber also rescues how Lublin's works maintained a socio-political bond with the context that housed them, inciting a broader dialogue between art and labor.22 In this sense, the last section also included a mix of beat and folk music, which showed the artist’s interest in recovering traditional culture in the face of the predominance of foreign music in those years.

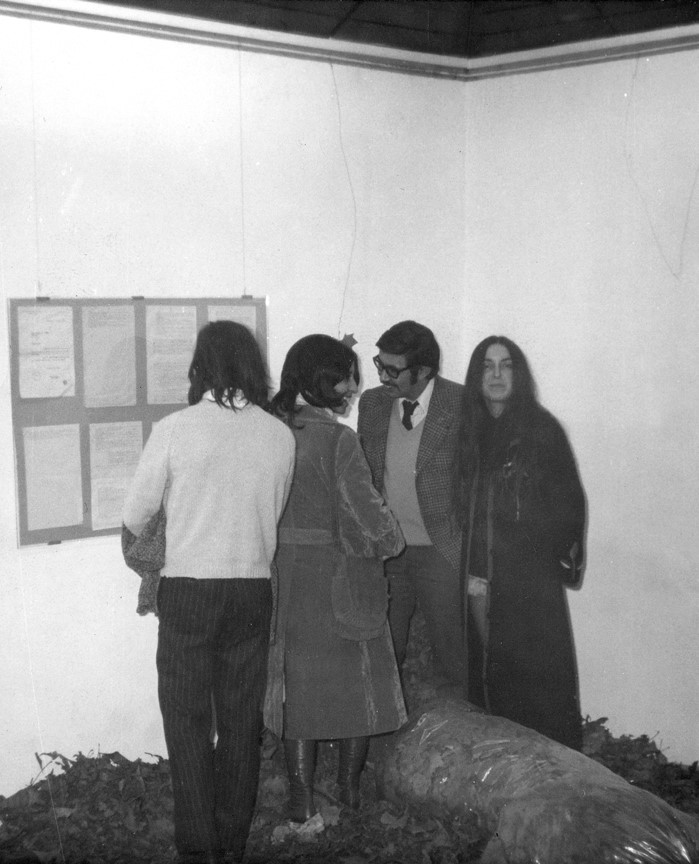

The quest started with these works continued with the project Lublin carried out in 1971 at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago, Chile. Cultura: Dentro y fuera del museo [Culture: Inside and Outside the Museum] is a project that brought her theories around culture and the role of art in society to life while placing the viewer in a liminal space. Its complexity lies in having blurred the boundaries between the museum and society, creating an intermediate space of questioning for visitors. According to Lublin, the outside and the inside reflected these two spheres of knowledge—the socio-political reality and culture—which she intended to integrate into a single continuum:

“There was no automatism between a perhaps revolutionary process [alluding to the election of Allende's socialist government] and the phenomena of knowledge, or science and culture. (...) Consequently, [this work] was also a critique of certain thought systems, of the implementation of dogmas, in the sense of automating, for instance, culture and revolution, knowledge and perception, etc. Knowledge is something much more complex than mechanical and automatic relationships.”23

According to Isabel Plante, in this work, Lublin sought to give an account of how policies of inclusion and exclusion operated within museums through their specialization of knowledge and valuation of some images over others.24 The work was once more organized as a walk. Outside the museum, visitors were faced with images projected on television screens with the most recent and relevant political events in the country. Upon entering the museum, long conceptual panels gave an account of the most important changes that occurred in the history of various fields such as economics, sociology, chemistry, philosophy, and psychoanalysis—a research work Lublin developed together with a team of academics and professionals from those fields. Upon completing this itinerary, a series of renowned works from across art history were projected on plastic curtains that visitors could go through. By combining the museum’s internal and external spaces, the installation pointed out the two differentiated spaces while also showing their mutual correspondence. Lublin aimed to demonstrate the intrinsic connection between the simultaneity of the "cultural" processes that take place on the inside and those of the political-economic reality that occur outside the museum space. With this, the artist intended to show how the knowledge production carried out from art is not bound to a certain space but continues wherever the viewer decides to take it.

In 1974, Lublin was invited to the exhibition Art/Video Confrontations at the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris, where she continued with the premises of the installation she made in Chile for Interrogations sur l'art. Discours sur l ́art [Interrogations into Art. Discourses on Art]. In it, the artist once again includes video to generate a live dialogue with the participants: while their answers were being recorded, they could see themselves talking on another screen, documenting their gestures and expressions while speaking. Somewhat in tune with the therapeutic format, Lublin welcomed visitors in a simple environment composed of a cushioned bench and a banner with questions that encouraged dialogue, such as: "Is art desire?", "Is art a feeling?", "Is art knowledge?” As an artist, Lublin emphasizes her role as an intermediary between the viewer and the work, which gives the interviewee back his own gaze projected on the screen. This active research format is realized by creating a visual archive that compiles reflections from intellectuals, artists and the general audience on the artistic practice, reflection, and discourse. Each presentation was organized as a collective workspace, open for visitors to exchange ideas, almost like a small theater on whose stage visitors, publicly known or not, could interrogate art and its meanings.25

The same year that Lublin carried out Cultura: Dentro y fuera del museo in Santiago, Cecilia Vicuña also had her first solo exhibition: Pinturas, poemas y explicaciones [Paintings, poems and explanations] (June 15 through 27, 1971). A few months later, she produced a site-specific installation for the Sala Forestal at the Museo de Bellas Artes called Otoño [Autumn] that lasted only three days. This work, together with the painting-installation called Biombo (Casita para pensar qué situación real me conviene) [Folding screen (Small House to Think What Real Situation Suits Me)] (part of the solo exhibition), not only accounts for the social and political climate of the moment but also for how Vicuña invited viewers to place themselves in other positions. For Otoño, the artist covered the entire room’s floor with dried leaves—some scattered and others bagged—creating a depth of up to a meter. At the back of the room, visitors could read the text “Diario de Otoño” [Autumn Diary]. The installation invited visitors to play with the leaves, to feel their crunching as they walked on them, and to assemble their own sculptures. Vicuña describes it as a work to be appreciated internally, beyond the gaze, highlighting the aesthetic experience that takes place inside the body. This factor does not overshadow its political side, on the contrary, it rather exalts it: “A work dedicated to joy is not apolitical because it wants to make people feel the urgency of the present, which is the urgency of revolution.”26 In a different way to Lublin, Vicuña suggests here an interpenetration of the inside/outside, breaking the sterility of human-made architecture with remnants of the natural world.27

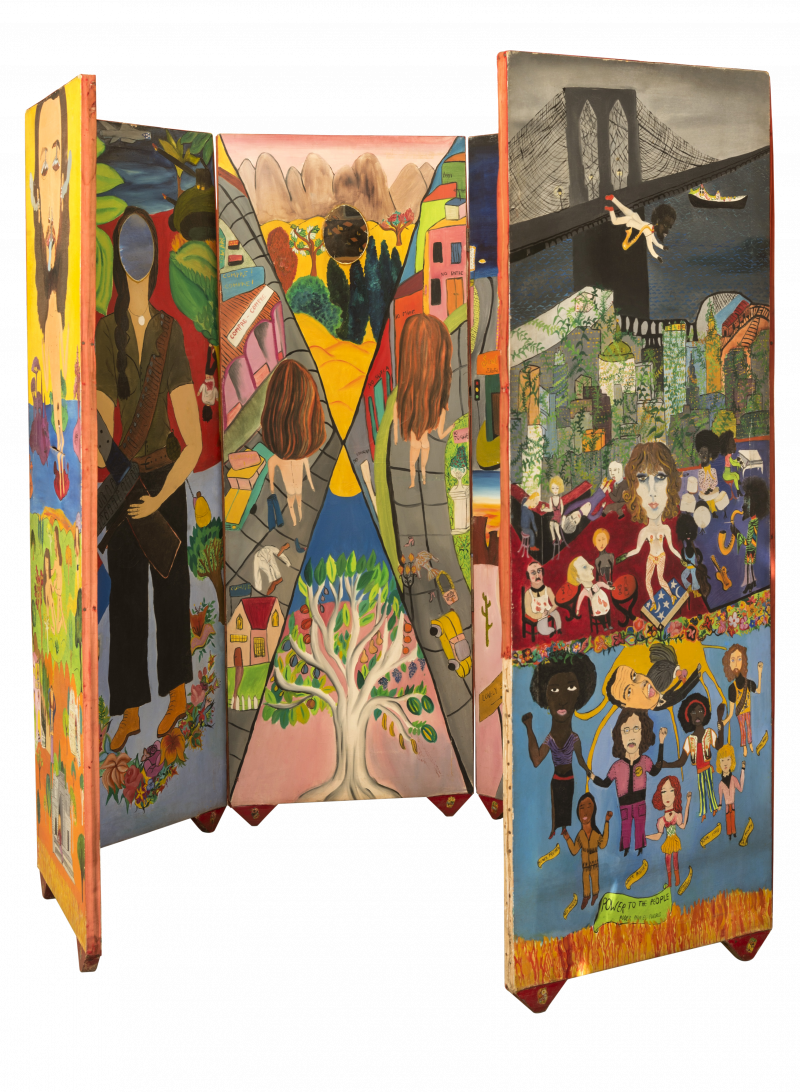

On the other hand, the folding screen was composed of 12 panels with oil paintings on both sides—six on each side—and joined together by hinges. This work is more complex in its reading. On the external side, it presented imaginary and real scenes that portrayed the democratized scenario of art and education: school buses transformed into classrooms, collective work, and rooms for teaching to read and write. On the inner side, there were six characters chosen by the artist that represented different paths to follow: a man held by a girl burning in flames in front of the Vietnam War, a poet, a singer, an educator, a guerrillera with a rifle, and a naked couple walking in a city that encourages consumption. The face in each character was replaced with a mirror, where people could see themselves reflected and, thus, choose with which character they identified.

The external panels portrayed the scenario proposed by the artist in her 1974 reading in London, where the democratization of art and education had reached greater spread among small populations far from the city. In parallel, Vicuña developed other pedagogical proposals in non-institutional spaces, such as the creation of a seed bank and local trees for their studying and subsequent planting. According to Carla Macchiavello, this action confronted the artist with the following questions: "Where does knowledge come from and what does it feed on?, can it be transplanted? If education is an act of cultivation, shouldn't it be connected to the land itself, to what’s our own, understood from the ground itself?"28 These questions will be present in some later works and projects, such as the Oysi School, in Caleu, which she founded in 1995.

Tying the Knots

The selection of these artists and their works responds to a need for tracing the correspondences around the practice of art and education nowadays, as disciplines that work together and generate spaces for reflection and interdisciplinary action. Lea Lublin lays out in her writings and works how the gaze is conditioned by the culture and education we receive. Artistic practice, no matter its medium, is always linked to and in dialogue with society, and ultimately, with the presence of the people who activate it. Her attempts to account for other ways of seeing, whether from the dark, projecting images on transparent plastic curtains, or creating a continuity between the internal-external space of the artistic institution, respond to the search of creating a new kind of awareness in the viewer and encourage experience as a basis for generating knowledge on their own. As in Vicuña's works, the body, intuition and the senses are fundamental for this passage.

In her case, her experience in Chile before Allende's inauguration laid the foundations for a practice that is articulated from small big gestures, in collaborative works and poetry as a means to change the society in which we live. While we have talked about their more interdisciplinary installations and works, both artists also used painting as a format to account for these other narratives. In the case of Lublin, deconstructing the image and its multiple processes and layers of meaning. Her reformulation of the concept of "space-distance" begins in painting and moves onto the social space, leading her to affirm that this is the element of a new transformative relationship: "Art can and should act as an art of transformation. For this to be possible, it must first question itself in order to uncondition, demystify, and deculturalize.”29

In Vicuña, painting unfolds from the elaboration of her own language, through which she recounts her social, emotional, affective, and cultural world. Research into the imagery present in Mayan and Parakas codices also reveals other forms of narration and perspectives that differ from the one introduced by the European Renaissance. Let us remember that colonization forced a way of seeing and representing reality, mainly through painting, establishing the concept of three-dimensional perspective to generate an illusion of reality. This type of perspective differed and clashed with the cosmogony and the space-time conception of indigenous communities, based on a continuum between the future and the past, and an absolute integration between all the elements of nature—including the human being, which is part of it and not superior to it. All the elements present a self-awareness, generating a very different order from the hierarchical, violent, and patriarchal "order" established by colonization. The retrieving of indigenous cosmology and Buddhist philosophy is present in many of the artist's works: from her precarious objects, the palabrarmas, the quipus, the thread installations, to banners present in the public actions and workshops developed during the 70s in Bogota.

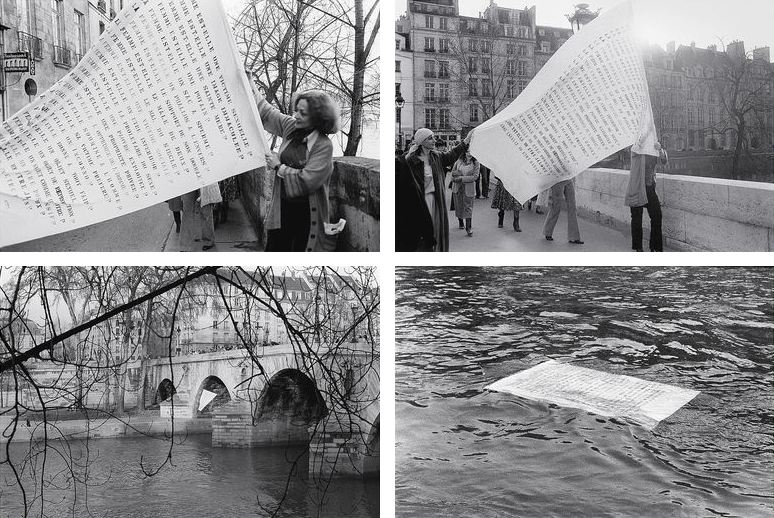

Another factor we can link is the use of language and words as a research format and for creating other realities. Lublin approaches it from a study of semiotics, sociology and the methodology of psychoanalysis. In later works made in Paris, language is also a means of protest and reflection, as in the iterations of Discours sur l ́art and the performance Dissolution dans l ́eau. Pont Marie, 17 heures [Dissolution on Water. Marie Bridge, 17hs]. For Vicuña, being not only a visual artist but also a poet, language is a prime component that allows her to imagine new realities and to investigate the layers of meaning hidden in words. Writing makes up only one part—the visual—since her methodology also appeals to the musicality and elasticity of words in their oral format. These free creativity exercises were also developed within the theatrical field, as well as in her workshops with children in Bogota and Caleu.

The works featured in this essay attempt to give an account of how both artists developed searches linked to the active perception of spectators, to the potential knowledge relationship generated between the work and its perception—understood not only as perceiving but as producing meaning, as Merlau-Ponty proposes.30 The ability to think for ourselves arises from that exchange, to receive and question from the here and now what the experience presents. In this sense, I dare to suggest that both artists sought to promote paths for a critical education: one capable of generating questions and concrete actions in different scenarios. As Marina Garcés argues, the ability to problematize the scenarios in which we live is a fundamental premise for being able to imagine ourselves, from the continuous creation of a we and the collective.