Luis Romero: Regarding the Yanomami term wã të (to retain, to learn): How are your learning rituals-processes? How is the knowledge transmitted in Yanomami culture?

Our Stories Tell Us About Where We Come From

03/18/2022

with Luis Romero

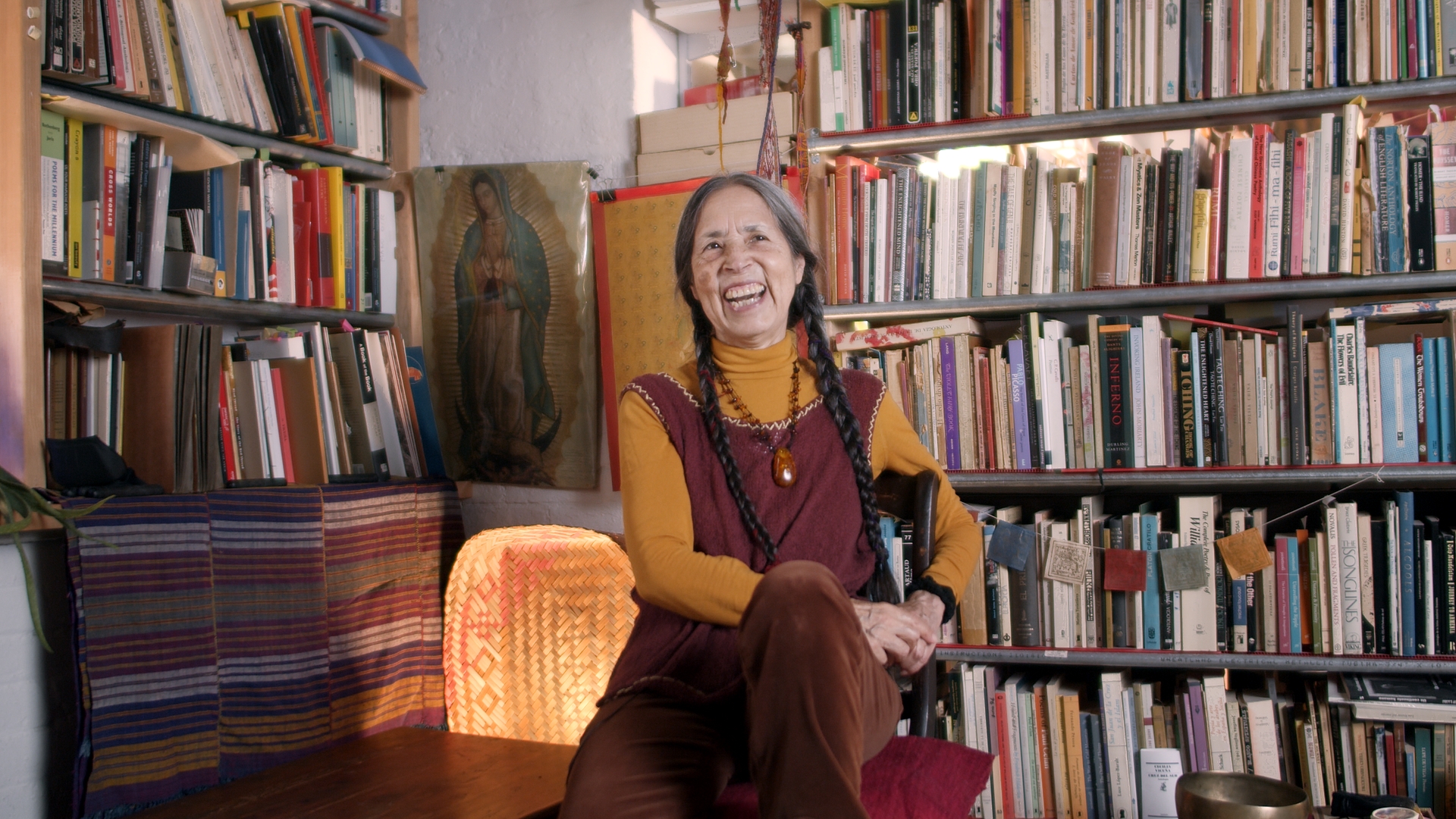

Placed between cosmological and geographical frontiers, the Venezuelan Yanomami people go about their daily life amid physical and idiosyncratic challenges that question the validity of indigenous beliefs, customs, and ways of life. From this Amazonian territory, artist Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe provides a testimony of their collective history through his drawings, which reach us from an extraordinary bond: his deep friendship with visual artist and cultural manager Luis Romero.

In this conversation for LA ESCUELA, Luis Romero shares reflections and anecdotes of his relationship with Sheroanawe, which spans for over 20 years, intertwined with testimonies of his great artist friend. Thus, based on the premise of the term wëai: (teaching through example), LA ESCUELA___ talks with Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe about the ancestral knowledge of the Yanomami culture and the particular ways in which it is transmitted.

Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe was born in 1971 in the small village of Sheroana, near the headwaters of the Orinoco River, deep into the Amazon forest. He is an indigenous artist currently based in Mahekoto-Teri (Platanal), a Yanomami community in the Venezuelan Amazon.

Before he began to practice art, Sheroanawe acquired valuable knowledge that allows him to survive and lead a life like any other Yanomami man: hunting, making bows and arrows, fishing, recognizing the different types of plants and animals that are useful to them, stories and tales from the oral tradition, among other activities of their culture and environment. During those years, he grew up together with other children from the community, participating in festivities and initiation rites typical of their village.

Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe: We learn by watching and listening to our elders. From a young age, we are interested in many things, so we accompany them to hunt, sow, make baskets, or fish. We sit and listen to the stories of the shamans, as well as when someone travels, goes hunting, or visits another shapono

Years later, Sheroanawe enters the educational system of the Multicultural Bilingual School of Platanal, under the direction of Salesian priest Father José Bortolli at that time, where he learns to read and write in Spanish. In 1990, he crossed paths with Mexican artist Laura Anderson Barbata on a trip she made to the Upper Orinoco, where she started a training project for making handicraft paper in the community of Platanal.

What values do you recover from this pedagogical experience? Which transcend to your artistic practice?

For me, it was good because I was able to learn how to make paper. And I was initiated in other ways of painting different from what we Yanomami know, which is for baskets and on the body. We were also able to work in the company of other members of my community on a project that we were not used to, learning new things every day. We made a book for the first time, Shapono (2000), which tells the story of how we were taught to make our house.

During the early nineties, Sheroanawe learned how to make handmade paper from natural fibers and became a master papermaker. He researched plant fibers from the area that were useful for papermaking along with Anderson. The two founded the Yanomami Owë Mamotima project [The Yanomami Art of Papermaking] around 1996. In its beginnings, a large group of members of the community focused on the production of books, notebooks, and cards for internal use and commercialization. The Yanomami Owë Mamotima group then took on the task of compiling the story of the mythical twins Omawe and Yoawe2 —as narrated by Shaman Makowe— who, through their experiences, taught the Yanomami people the art of building the community house: the shapono.

Is there a specific space dedicated to learning and education inside the shapono3? How are the social dynamics within this space?

There is no dedicated space for that, we gather sitting on the ground anywhere. In front of a shaman's house or lying in our chinchorros (fiber-knit hammocks) in the evening, we talk and listen to each other in the darkness and silence of the night.

In 2004, Laura Anderson and Sheroanawe were invited to participate in the Fundación La Llama residency program in Caracas. There, for two months, they transcribed the notes they had collected for almost a decade in Upper Orinoco, basing their research on field data and books and documents from the collection of the library of the Botanical Garden of Caracas.

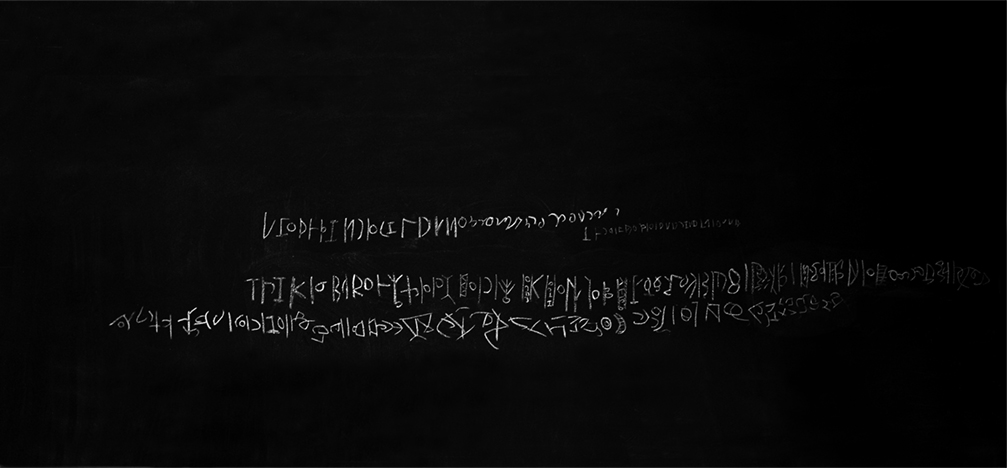

Sheroanawe then returns to Upper Orinoco, where he sits for long days to perform a self-imposed task: to compile from his mother the extensive inventory of symbols and drawings, traditionally used by women in baskets and by the community in general in body painting. This work aimed at the difficult task of retrieving part of the oral, graphic, cosmogonic, and traditional memory of their people. From this experience, Hakihiiwe begins to develop a language of his own, characterized by synthetic and minimal drawing.

His entire work revolves around the intense relationship he has with the jungle he inhabits. These bonds in his work are communicating vessels that extend across the realms of the personal and the collective. His work is, thus, a contemporary revision of the cosmogony, the natural imaginary, and the social and cultural environment of the Yanomami people.

"Sheroanawe's drawings are not symbolic representations nor metaphors, they are maps of a complex ancestral cosmovision: they present us, as an intellectual and spiritual challenge, with an invitation."

How is this bond with the lived environment developed? What can we learn from your ways of relating to nature?

We respect the forest (Urihi); we do not take more than we need, each thing has a use and a reason. Our stories tell us about where we come from, of how Omawe and Yoawe taught us to build our shapono, how they discovered water for us, or how the day separated from the night. All that was a long time ago but it is true: everything we have is in the forest, if we do not take care of it, we will have nothing.

Sheroanawe's art is a tremendous living archive of a memory preserved and stimulated by his artistic, aesthetic, and rational curiosity. His drawings and paintings are posed as a link that binds the ancestral with the contemporary, existing between two or more universes, and simultaneously traveling across several times.

From a blunt silence, his work invites us to reflect on the imbalances that take place in cultural hegemony. I always think of the great challenge implied for Sheroanawe in having to speak and translate from Spanish into his language a series of concepts and ideas which are not familiar and have no parallel in his language.

Many events are planned from a logic that is foreign to him, and this is a learning or challenge for him. I remember the first time I told him, back in 2010, that we were going to make an exhibition with his drawings. He did not understand it because the concept was not familiar to him. When he saw all the drawings installed in the gallery, hanging on the wall, he said to me, "Oh, so this is an exhibition! Then it shall be called: Oni tepe komi” [All the drawings are here together].”