Javier Zugarazo: You have written about education, specifically art education, picturing it as a factory of coloniality. How does this factory work?

Re-imagining from the Power of Shared Delirium

danie valencia sepúlveda (Ayutla, Jalisco, Mexico, 1990) Herrorist, educator, researcher, cultural programmer, and independent translator. They initiated the Círculo Permanente de Estudios Independientes (CIPEI), a counter-pedagogical research platform that, among other projects, runs the ongoing de-formative course 'Menos Foucault, Más Shakira' [Less Foucault, More Shakira]. They is the current editor-in-chief of Terremoto magazine.

danie valencia sepúlveda: I would be interested in talking about education in general as a factory of coloniality, not only art education. It seems to me very necessary that we recognize the role that education plays in terms of being an updating device for all the desires of the State. And along this line, to think that the State is the heir of the entire colonial apparatus and coloniality is this current moment that ends up being some sort of lethargy of all the violence exerted in the 1400s. Now, the issue here with art education has to do mainly with how the very notions of perception and even of aesthetics and knowledge around these two elements also end up being assigned from a linearity constructed directly by the West as part of the modern colonial project. So, what I call the factory of coloniality has to do with how the desires of the modern colonial project are activated and reinforced in this education.

For instance, let us think about the knowledge circulating through Latin American art schools: Which artistic productions are recognized as such? What is not recognized as artistic knowledge? And also, which artistic practices are not recognized? This school or factory ends up validating what can be taken as a legitimate practice or knowledge, so here is where I'm interested in making a small incision.

Do you recognize any artistic strategies or practices that could allow us to break this structure, not only of the school but also artistic?

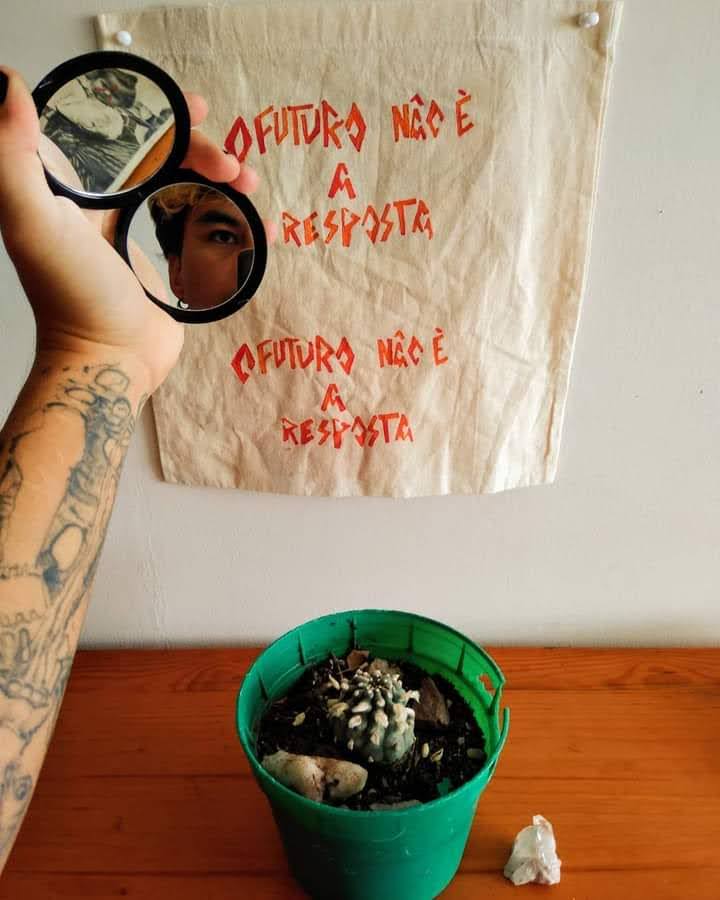

I think a lot about sovereignty as a delirium. I am quite interested in considering or taking back the power of collective delirium as a starting point to propose new ways, invent other strategies to reach that idea of sovereignty that we need to contemplate. To think of it in not only imaginary terms but also as political imagination, as a moment from which all forms of creation can be sheltered.

What do you mean when you speak of sovereignty: the sovereignty of the bodies, community sovereignty, sovereignty of the people?

It departs from the idea that we must acknowledge our context, which is that we do not belong to any community, as we inhabit a voracious and compulsive form called the city. This fact distances us from approaching the idea of community sovereignty. Therefore, I prefer to think of sovereignty as emerging directly from error. This means assuming the fact that, as we live in cities and inhabit this daily chaos, we can also think of ways to emancipate ourselves from these colonial forms of knowing and doing. Going back to the question and returning to the artistic part, I believe it is essential to build ideas of sovereignty regarding knowledge and artistic work, thinking that perhaps the artistic could be one thing while art has other foundations.

What non-individual strategies could allow us to weave networks in the urban context?

I believe taking up the idea of delirium would allow us, at some point, to explore the desires that lead us, for example, to name what we understand as ‘community,’ which is also a complex thing because, at least from the sixties onwards, the concept of community has more to do with notions of a market niche than with something that invites us to build a world together. It is more like a form from which we identify ourselves through consumption, not only materially but also in ideological and even identity terms. Because identity is also—or ends up being, due to being captured by neoliberal capitalism—a means of consumption. However, if we were to consider once again dwelling in delirium, we could begin to map desires that can lead us to the construction of something communitarian—which is not something that does not happen. We have communities of affection—as Sayak Valencia would say—which are those we weave and strengthen daily from different political horizons. And those communities of affection, ultimately, also allow us to sustain or harbor or bring back what we could call the vital force, or what makes us remain in this and other realms.

Affective Communities

Affective communities also become strategies to share knowledge outside of schooling and academia. How are affections involved with knowledge to achieve desire?

I like to think of desire as the perhaps somewhat basic impulse that makes you get out of bed and start the day or night, or whatever the moment people get out of bed. I like to think of it from that place and in that sense. So, it seems to me that desire is what moves us; thus, we must understand that desire also mobilizes the extreme-right wing. In other words, the question here would rather be in terms of inviting us once again to recognize that knowledge, before being institutionalized, is knowledge, is wisdom that is already there.

You see, ultimately, there is an institutionalization of knowledge in the sense that there is a colonial legacy in all this. There is a reason why we continue to think that knowledge can only be accessed through universities or schools, stripping us of the idea that we can build knowledge in the street or with a neighbor, even if the relationship with the neighbor isn’t good.

We have been stripped of the idea that we can build knowledge with other forms of life, so we limit ourselves to thinking that knowledge can only be constructed from the word, but knowledge can also be an exchange or flow. It would also be necessary to assume the radicalism present in generating knowledge with other species, allowing ourselves to be affected by them as well. Let's say that we would have to venture into exploring those horizons, to share the delirium from this idea.

What could be the strategies to escape from making this colonial projection?

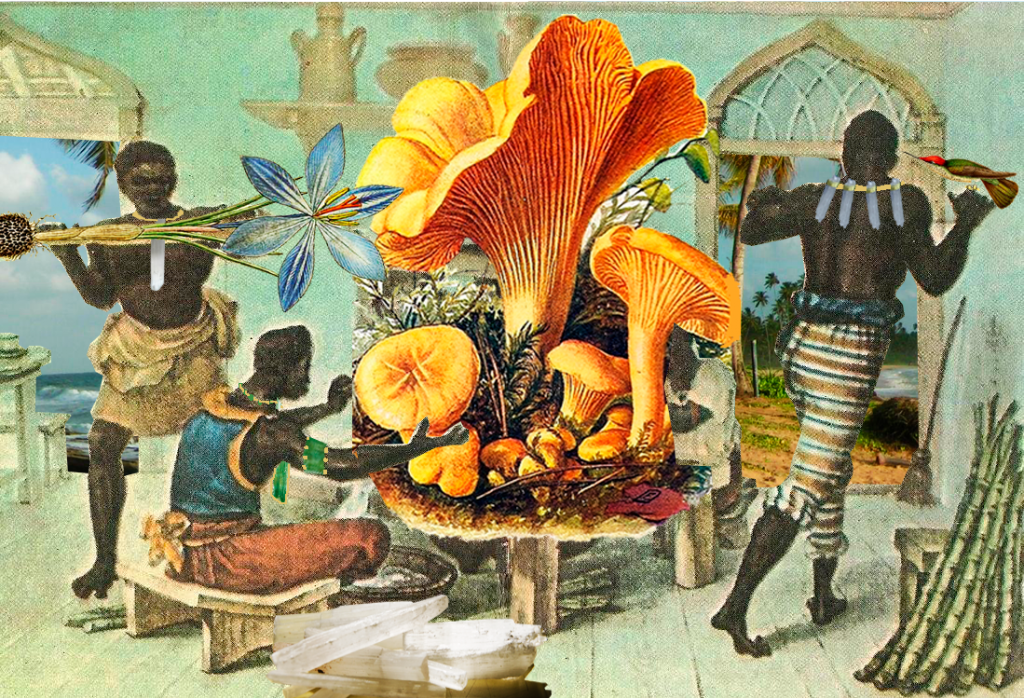

I don't think there is an inside and an outside, but rather a constant negotiation to be able to deal with the onslaught of that centrifugal violence, which at some point throws us to the borders, but we are inevitably inside. For instance, thinking about the whole issue of coloniality—in the sense of museums and schools being colonial devices—the project contra pedagogía racista was a collaborative exercise that involved a series of devices that were activated through interventions and invitations to different agents to talk about anti-racism and regimes of representation. These agents were diverse, such as artists and the group of the independent circle of permanent studies "Menos Foucault y más Shakira." These moments also allowed us to activate a counter-pedagogy in terms of a collaborative exercise, where we were all willing to exchange knowledge, feelings, and practices related to what was being activated at each moment. So, it seems there is no escape, but through negotiation, it is possible to deal with the colonial onslaught.

Therefore, we can speak of being able to inhabit the split that the museum, gallery, or cultural institution itself has produced. That very crack allows us to stop operating in the direction of the institution's desires, which in this case was the museum. Because we know that museums have a mainly colonial, racist, and fetishizing past. There are a series of things that come from the cabinet of curiosities, from the display of, let’s say, “freakness,” and here, the freak will always be the indigenous, the black, the cripple, and so on. Museums come from that tradition and it seems there is no way to escape that. But there are ways to negotiate, and for this, it will also be relevant to know in what collaborative ways we can subvert a little the idea of the white cube, or of the museum, or, in short, the institutionalization of knowledge.

So, how to deal with the risk of self-exoticization? How to emphasize that it is a vindication and not a self-exoticization?

The risk is always present, but I believe we must embrace it. I also think it depends on what we understand by self-exoticization. For instance, Spivak talks about strategic essentialisms, which are these sorts of forms in which the political reactivation of identity will allow us to construct and negotiate with the colonial racist system in order to navigate it. I am not saying we will come out victorious or unscathed from this crossing; in fact, not at all, because there will also be injuries that are not visible and will remain imprinted in our psyche, in what we understand as "mental health."

Creating Splits

Could one of these strategies be entering the spaces and, let's say, infecting them? Not knocking them down but cracking them. As you were saying, creating splits.

It happens that, generally, when a person is what we could call racialized or belongs to a socially and historically minorized group, it will always be taken as self-exoticization. But it is the experience itself that is seen as if lying on this velvet bed, so to speak, but it is never a velvet bed; it is always a fucking stone bed, like of the coldest concrete possible. However, it will be taken as such when it is a white person talking about their own white misery. When it is a cis, hetero, white body that is talking in the first person, it will never be taken as self-objectification. Whenever someone speaks of fetishizing or self-fetishizing, it will always allude to the speech or actions of a racialized body, of a body produced as a "minority."

Yes, in the end, the word exoticization also becomes punitive. And so, the self-exoticizations that you embody—that is, the vulnerabilities you are showing to make yourself visible—are seen in a punitive way.

It’s what we were saying earlier: there is no way out. It is a matter of assuming the risk, which will also involve embracing error. This implies knowing that identity as such is a big trap, especially if we think of it in this neoliberal context, in which it is even a consumable good. So, in this sense, there is no way I can talk about my indigenous grandmother and her knowledge without that being taken as self-exoticization. Even when my interest is not that this knowledge ends up in an artist's book or in a catalog, but to turn this exercise into a collaborative tool through which we can continue building and digging, to be able to unlearn and un-know, at some point, all those issues established by the device of mestization itself—as Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil would say.

How do we unlearn de-indigenization? How do we unlearn all the violence concealed under the political fiction called mestization, or more specifically, mestizos? So, I think it is a risk we must assume, as long as we keep in mind that it is a negotiation we must have with institutions and in our daily lives. We will have to make decisions to continue building that world, perhaps toward bodily sovereignty. It all seems to go together, even a sovereignty that could be epistemic: of imagining.