Ana María Garzón: What made you decide to form a collective?

Sharing Knowledge in Spaces of Curiosity

Laboratorio Disonancia is a transdisciplinary collective formed by Patricio Dalgo and Jorge Vásconez, founded in Quito (Ecuador) around 1997 as a sound experimentation project.

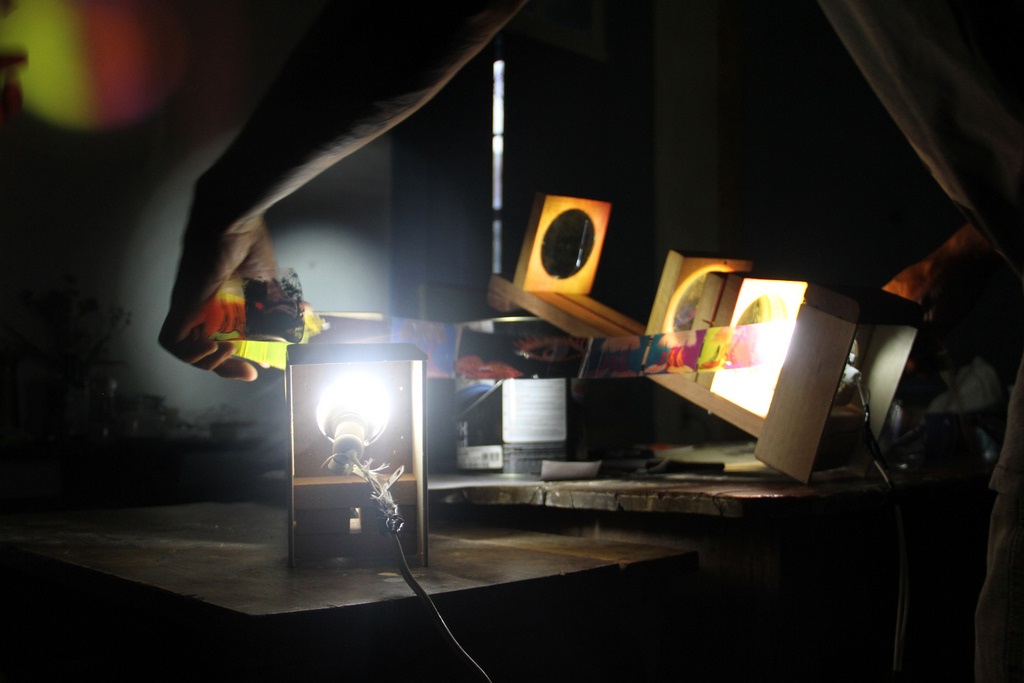

Since 2008, it has unfolded as a collective dedicated to electronic (analog) experimentation, both sonically and visually, in its different ranges of possibilities, focusing on the development of projects that combine experimentation, artistic action, technologies, and open knowledge.

Laboratorio Disonancia

Patricio Dalgo: I think it was gradually, in a sense, the idea of sharing knowledge, sharing things that make us curious, which is something that continues to be a fundamental part of the laboratory. As the days went by, we had findings that we wanted to share in our experience. The lab started between 1997-1998, although we are not very sure. The interests came more from an underground movement than from an institutional one, and then, as time went by, we understood that these practices could also be part of our artistic production.

AMG: What were the first projects you did together and which one did you start teaching other people?

PD: We started a sound experimentation project where we all got together to damage guitars and keyboards, to try out toys, to look for sounds...

Jorge Vásconez: From electronic percussion, or what I thought would be an electronic drum set, and we formed several music groups, with several names.

PD: Maybe it was a bit of an adolescent and anti-institutional thought, not to be so formal, which could also have something to do with not wanting to be known as a band, but to play in the events that we were able to sneak into, which range from bars, streets, more formal concerts, and invitations like the Festival of Contemporary Music.

The idea of the laboratory came from our concern about the name. We used to call ourselves more clownish names and when we changed our name to Laboratory for Research and Experimentation of Dissonance, everything took a different direction; after being completely informal and working on the side, everything became more formal. Maybe we also started to take it more seriously and that is where this project comes from, collaborating with workshops and sharing things with other projects, later we decided to share with children.

When we proposed this, we did not think of working with children because they are an easy audience, but because we thought that it would be a great learning experience for us because of the informality, the curiosity and also all the drive that children have. They helped us a lot to generate new concerns in terms of sound, how to play and how to get things out of it. It was a wonderful project.

Outside the city

AMG: Where did the idea for Sound Drifts come from?

PD: There are several angles from which we approach it. The first is the decentralization of urban practices, and later, since we didn't have a messianic zeal or community projects to save the community, we thought of approaching places where we like to be and spend time. It was a kind of show that went around the communities.

AMG: What was the framework of your first event?

JV: There was a call for a festival of Aviones de Papel, for which we proposed to do this project with them. There were several options for locations and we decided to start in Puerto Quito.

AMG: Let's talk about this interest in working with low technologies, recycled materials, and things that work according to the "do it yourself" logic.

JV: Well, because we come from that, from precariousness: we didn't have a computer, we had an electronic piano that we started to manipulate to make sounds, and that's how we discovered that with a microphone with an electric base mounted on a tin can, you can build a sound generator, or an "instrument".

PD: Of course, but it also comes from our suggestion that if we can do it, anyone can do it. So it's about working with the materials you have, because this idea of low-tech and high-tech depends on the context. I once heard someone say he was doing low-tech, but he was using four computers and six projectors. Of course, if you relate that to a European or American production, it is low-tech. Within low-tech, there is a lower terrain, and that is where we like to be, so that it is not something that can be privative or distorted by economic issues.

AMG: Why teach this?

PD: For us this is also a field of constant experimentation, our proposals are in the tone of learning. We come as tutors and of course we are involved in teaching and learning through the dialogues that are generated. The idea is to propose a learning environment where we have the role of tutors and the people involved in the workshops are the apprentices, but the teaching-learning processes are multidirectional. I think it starts with some curiosity on our part, and then we use a lot of resources to get to different things; we also take a lot from plastic arts, from drawing, we record with cameras, they are not fixed projects.

AMG: What comes first, the form you want or do you learn from what is there, do you go out into the community and then build?

JV: We usually have an idea that changes along the way, depending on how things are going, a lot of ideas come from the dialog with people and we connect with them in their own projects, they invite us to participate in their things. I like that a lot because I feel that they have accepted us as friends.

Being an apprentice

AMG: You both teach in formal spaces and at the same time explore spaces in your practice that are not so formal. What is your political position regarding pedagogy?

PD: The first thing we think about politically is the role of the tutor. When you are a tutor, you work in coordination with the apprentices, but you also start as an apprentice. When we go to a territory, we learn a lot; and it is not a demagogic question, for example, when you are in Puerto Quito and they go to the river to swim, even if you know how to swim, you are a city dweller who is going to learn how to swim and how to behave in their context. So it is not a vertical proposal, but always a dialogical one, and that is where the learning environment takes place, which works by proposing some tools to see what they can think of to do, looking for innovation, the playful part, also curiosity and what other type of functions we can find in these situations. Another important part is always using minimal resources or adapting to the context with the things we have at hand to solve things on the spot.

AMG: It also involves thinking of this experimentation methodology as something very free, not coming in with scripts, but waiting for something to happen with the materials available.

PD: Yes, it is this idea of a "breeding ground" that is very laboratory-like: creating a suitable environment with some tools will lead to experiences that, to our credit, have been quite enriching for our training in the pedagogical field. I studied fine arts and, strangely enough, they never teach you pedagogy, even though we all end up teaching in some way at some point in our lives.

AMG: How did you go from experimenting with sound, with noise, to experimenting with the image, to making home movies?

JV: The idea was to propose an experience that didn't require us to be understood, so there were things like headphones or gadgets, toys where you could stand and watch if you wanted to, play with the slides to project, get on the chairs and pedal, use the simple resources that we put in the room that could have a high learning impact. It was the experience of moving this archive to a place where it could be read in a different way, but it wasn't a literal step, but we adapted it so that the experience was different.

AMG: And what do you think it is that people learn in your projects or workshops about building devices, generating sounds and images?

PD: I think it is about opening curiosity and encouraging people to create things or experiences with minimal resources.

In fact, we have seen some people who have found solutions based on the way of working that we propose to them, understand how the device works and build one or make some variation or modification... So these kinds of exchanges end up becoming collective bits of intelligence—these are another door not an end.