«We hope, however, that for future days, in a world that will necessarily have to be rationalized—in which the grossest injustices, if not all, must disappear, and in which man will no longer continue to be a slave to the misery of a chained work, a work that is never his creation, as Gorky aspired it to be, but that has not yet been able to pass from servitude—for the new world that is so eagerly awaited and for which there are cries in all tones, these aspects of man's expression that we have studied will acquire their true value. The school will thus have to review its programs and methods, adjust its directives and orientations and give this problem all the importance it has, for its own social needs, those of a broader solidarity and understanding among men, developed from the individual, who will then have been definitively saved from shipwreck.» Jesualdo Sosa, La Expresión creadora del niño, 1950.

Jesualdo Sosa: A Transit-Pedagogy

06/10/2023

by Pablo Pineau

The notion of ‘transit-pedagogy' expresses a position on the relationship between the socio-economic, political and educational spheres that places him among those who disagree with the mechanistic views that distrust schools' democratizing role.

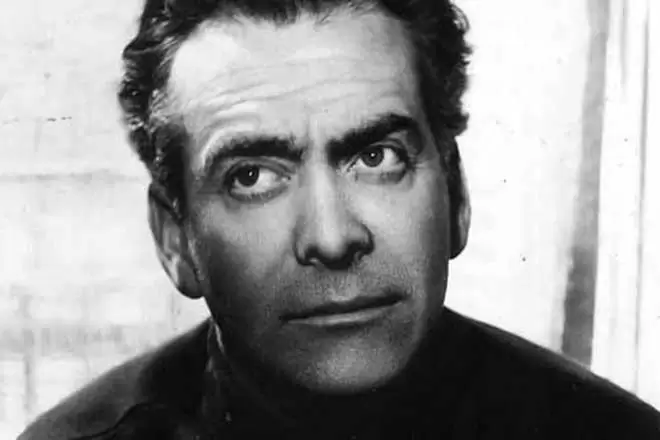

Jesús Aldo Sosa Prieto (1905-1982), better known as Jesualdo or Jesualdo Sosa, was born in Tacuarembó, Uruguay, on February 22, 1905. At the same time that he advanced in his studies, he worked in minor tasks with his family. He graduated as a teacher at the age of 20. A year later he obtained a position in a school in Montevideo, while he began to take his first steps in journalism and poetry. Due to continuous discussions with the authorities, in 1928 he requested a transfer to the rural school N° 56 of Canteras de Riachuelo, department of Colonia, on the Río de la Plata. There he married the headmistress of that institution, María Cristina Zarpa, who had been developing a very interesting pedagogical proposal of community bonding. He spent seven years there developing his main experience of educational practice, in a place "populated by immigrants where the most varied nationalities are combined and where the work was of rigorous effort," with family, social and economic contexts marked by hunger, exploitation, school dropout, and hard work from an early age.

The image he provides of this situation does not differ greatly from those of the rest of the popular Latin American sectors of the time. From the beginning of his action, he denounced the artificiality of the school task in those media, and questioned the education systems that naturalize social reality and present it as unmodifiable. He searched for and produced different strategies based on books, magazines and all the study and reading material he could access. Together with his wife, they elaborated a program to be implemented initially in the third year to which the whole school later adhered. The program articulated the need to respond to the educational and social deficiencies of the rural environment with the importance given to creative expression. Due to its trial nature, the program did not have a previously developed methodological strategy, but was configured as the work with the students and the community progressed. The only premise that was established from the beginning was the need to allow and develop "the creative expression of the children." To achieve this objective, two activities were implemented to organize the school task: the "centers of interest" and the cultural extension course or "school field trips." While the former were based on the need for students to decide on the topics to be studied and investigated, the cultural extension activities were based on the importance given to the relationship between the school and the community, with proposals designed beyond the classroom, such as field trips and artistic events. These not only explored the natural and social environment, but also turned the school itself into a local cultural center with theatrical performances, festivals, etc. Also noteworthy was a weekly newspaper called El Marrón, a name inspired by the tool used by the quarry workers to break the stone and an emblem present in the school's sports team flag, which consisted of different sections and reported on community events, the activities carried out by the school and, fundamentally, the actions of its students. From this experience, he published in 1935 his book Vida de un maestro, written in a confidential tone closer to that of an epistolary exchange than that of an academic text, where he narrates the daily life of that school. It is a class diary of a young nonconformist teacher who seeks options to the reality he had to live. Without naming them, the work is reminiscent of De Amicis' Heart: Diary of a Child, Tolstoy, and Anton Makarenko. As a consequence of the strong social and educational criticism that the book presented, he was dismissed from his position and forbidden to continue with his experience. Although censored by the Dictatorship of the time, the book not only quickly sold out its Uruguayan edition but also spread throughout the Spanish-speaking world. Jesualdo became famous as a result of these events. A higher level of maturity and systematization of his ideas characterized the subsequent period. The Spanish Civil War, and later the Latin American liberation movements such as the university reformist extensionism, the Mexican Cardenismo and the Cuban Revolution, found him definitively enrolled in the progressive leftist currents. In 1973 he withdrew from the Uruguayan public scene as a consequence of the coup d'état, which prohibited him from performing in any way and from selling his books, and he passed away silently in 1982 in Montevideo without seeing the return of democracy in his country.

Transit-Pedagogy

From the beginning of his teaching activity, his works were inscribed in the renovating paths of the New School from the critical attitude inspired by the first Soviet educators. One of the greatest values of his extensive written work is that he managed to appropriate elements from the experiences of Montessori, Decroly, Freinet, Makarenko, Krupskaya, and Dewey. Being a great reader of psychology, his pedagogy was also based on the contributions of Freud, Aníbal Ponce, Piaget, Vygotsky, and Henri Wallon. He also recovered the regional tradition with references to Simón Rodríguez, Juana Manso, the Cossettini sisters, José C. Mariátegui, and José Martí, among others. Thus, he belongs to what has been called the 'radicalized new school'1 in Latin America, composed of educators who did not limit their approaches and modifications to methodological issues, but broadened their gaze to other spheres.

Both their thoughts and their works analyzed the complex relationships between education and society, and thought of concrete educational practices through which it was possible to carry out modifications in the general context. They are considered pioneers in 'education through art,' and had an outstanding performance in political, trade union, cultural, and artistic spaces, extending their action beyond the strictly scholastic.

Throughout his works, he maintained the search for a synthesis between teaching methods and dialectical materialism. While reiterating that education alone is not a lever of history, he reaffirmed its capacity to transform society. For this reason, he opposed both uncritical and naïve methodologism—which had led some reformers to support authoritarian political regimes—and those who disbelieved the possibilities of social transformation contained in educational practices as being determined by the economic structure. For Jesualdo, although the school was subordinated to the economic-social structure, there are always contradictions that allow spaces in which strategies can be installed to modify it, based on "[...] a transit-pedagogy that must serve us in today's societies and the instruments that it can provide us for the best success of our task." For this reason, he supports the possibility of intervening from these spaces to fight for the profound transformation of education and society. Thus, the notion of ‘transit-pedagogy' expresses a position on the relationship between the socio-economic, political and educational spheres that places him among those who disagree with the mechanistic views that distrust schools' democratizing role.

The 'creative expression of the child’

To achieve this, one of his central ideas refers to the 'creative expression of the child,' to which he dedicates a book of the same name published in 1950, which can be considered the work in which he develops his ideas in a more finished form. He held that expression has an organic origin that manifests itself through predispositions, potential functions and tendencies that can be developed according to the influences of external conditions and educational action. He trusted creative expression as a strategy for children's liberation from the forms of alienation that, under the slogan of apparent neutrality, are exercised on them by an unjust society and a related school.

He accused the traditional school for not approaching expression as a tool that would help children to translate their intimate experiences, achieve knowledge, and integrate into the environment in an enriched way.

In opposition, he affirmed that every human being was capable of achieving an original expression to translate their own life experiences and to appropriate knowledge in an effective and lasting way. For him, children's expression does not differ in any way from the purpose of the artist who always tries to achieve the imprint (with the element that serves him) of what he aspires to express. Therefore, he argued that expression should be allowed to follow its natural course of maturation without repression in order to become truly creative, since all individuals have a particular expression that manifests itself in some material—word, line, rhythm, form, image, body, sound, etc.—which should serve for their communication and for their own and the community's development. On the contrary, when expression is repressed, children are subjected to the loss of spontaneity and originality with disastrous consequences, which manifests itself not only in the impoverishment of language but also in the emotional, relational and cognitive aspects, since expression is a central element in the production of all forms of knowledge. His proposal was based on what he called the 'present interests' of real childhood—"the center must be the child and the interest must be born of his present need”—a reworking of the concept of 'center of interest' used by the European New School, which he considered artificial. In his own words, his method "is an application of Marxist dialectics to the activities of the school."3 Hence his proposal to structure teaching based on the concrete reality of homes, their social and economic situation, and what was happening to each of the children, seeking to address their concerns, incorporate their initiatives and guide them in the creation of expressive solutions. Since then, many Latin American teachers have recovered and valued their particular conceptions to carry out educational proposals where expression and art, in all its manifestations, collaborate in the creation of individual and collective development projects in the marginalized populations of the continent.