Rubens Gerchman and the Pedagogy of Everyday

11/14/2023

If the goal was to de-academize the school, it was by no means to de-intellectualize it [...] Rather than being a space dedicated to leisure, to the so-called "disorder" of the time, the EAV became an unrelenting powerhouse of artistic production, in tune with the transformations that would mark the second half of the 1970s.

The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible.

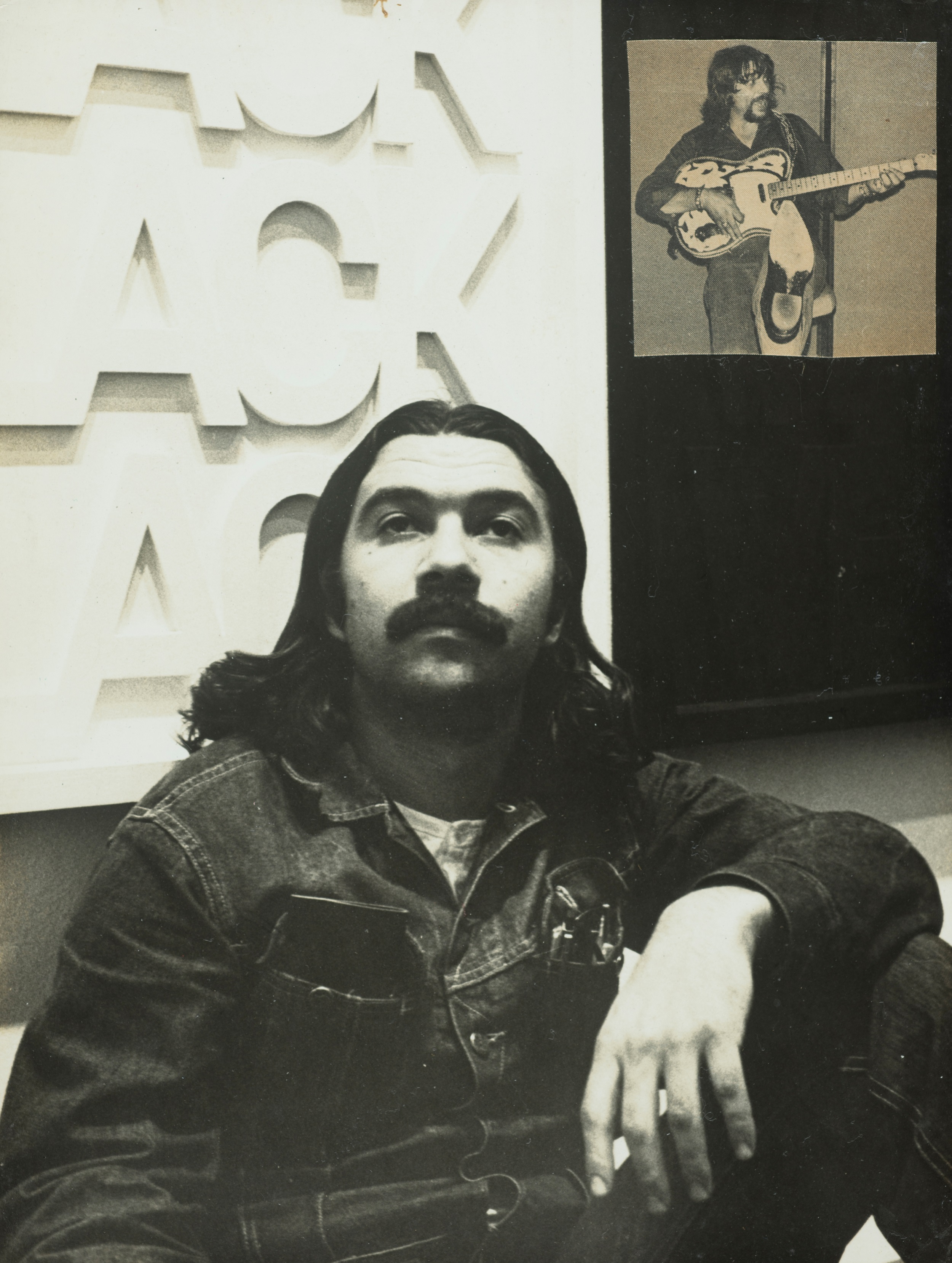

Legend has it that when Rubens Gerchman entered Parque Lage as the new director of the School of Visual Arts, his first act was to throw the easels onto a bonfire.1 In classes devoted to painting from live models, Gerchman introduced a long cane in place of a brush. In this way, control of movement was not restricted to the hand, but expanded throughout the body. The students began to draw standing up, rather than sitting down; the surface rested on the floor, not on an easel, and the model was in constant movement, rather than stationary.

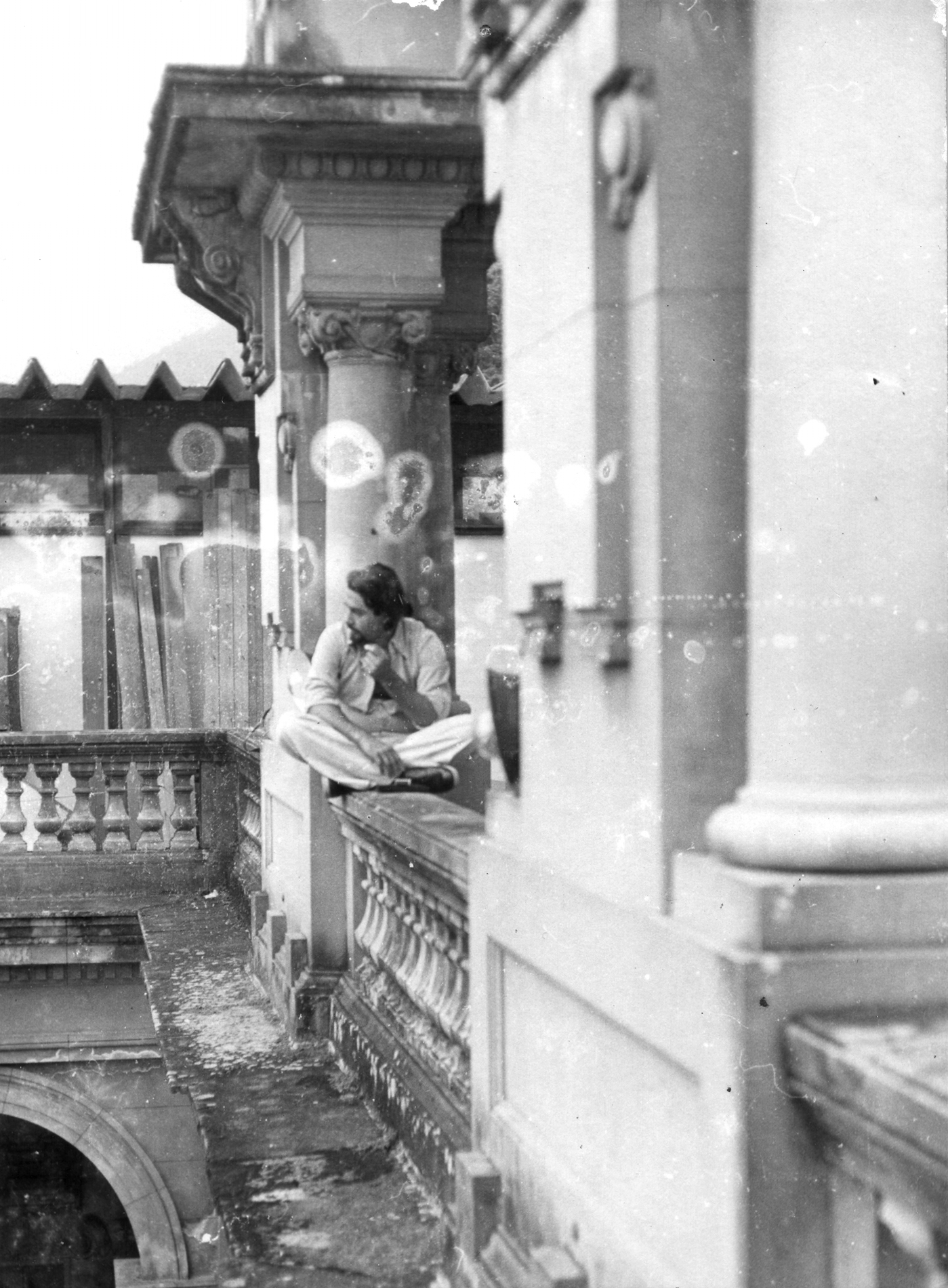

The old Institute of Fine Arts (IBA), founded in 1950 and moved to Parque Lage in 1966, became an open arts school, headed by Gerchman under the new name of Parque Lage School of Visual Arts (EAV). Under Gerchman's guidance as director of the EAV, between 1975 and 1979, the institution experienced an accelerated period marked by a new sense of effervescence and intensity. The former home of the Italian opera singer Gabriella Besanzoni, built in the 1920s in the Jardim Botânico neighborhood, ceased to be an academic space and was transformed into one of the most active cultural centers in Rio de Janeiro. Instead of training painters, the goal of the school became the integration of art and life, focused on a multidisciplinary approach and interaction between different fields of knowledge.

The new school gained a reputation as a bustling place, with renowned artists and intellectuals as professors, who offered “workshops” rather than classes.

2 In the evenings, the courtyard of the EAV was converted into a stage for performances and musical shows, such as the frenetic Verão a mil (Racing Summer) project, organized by the poet Xico Chaves, with performances by Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Luiz Melodia, Jards Macalé and Jorge Mautner, among others, as well as evenings associated with Nuvem Cigana (Gypsy Cloud), a marginal poetry group. According to the historian Heloísa Buarque de Hollanda:

«The EAV, around 1976, was already considered the great cultural center of Rio de Janeiro. It was at the EAV where Marginal Poetry, the most important literary expression of resistance, found a space for creation and performances, in events that brought together a huge young audience for literature, something which to this day is practically unheard of in the literary world. It was at the EAV that Francisco Bittencourt launched our first gay publication, Lampião da esquina [The Corner Lamppost]. It was there that the Lacanian avant-garde psychoanalysts took over the Freudian School of Brazil. It was at the EAV that the conductor and composer Joachim Koellreutter organized his historic twelve-tone music concerts. In short, at that time it was from the EAV that the cultural life of Rio and Brazil was propelled.»[3]

A new way of thinking and acting, focused more on practice than on theory, would define Gerchman's pedagogical method. If the goal was to de-academize the school, it was by no means to de-intellectualize it. The idea was to encourage exchanges between artists and give to the students a knowledge of contemporary art, outside the academic tone that had previously dominated.

Rather than being a space dedicated to leisure, or to the so-called "drop out” sensibility of the time, the EAV became an unrelenting powerhouse of artistic production, in tune with the transformations that would mark the second half of the 1970s. Brazil was then being ruled by a military dictatorship and when Gerchman took over Parque Lage in 1975, towards the end of the regime’s “leaden years,” the urban guerrillas had been decimated and the student movement dismantled. Armed action was no longer a viable option, and many young people chose political disengagement, which was viewed by the orthodox left as the product of alienation.

The EAV emerged as an alternative option between, on the one hand, the “drop out” group associated with the counterculture and the hippie movement, and on the other, the politically committed left and its attachment to nationalist-populist cultural production. According to Heloísa Buarque de Hollanda, “it was a time when the university did not speak out, nothing was said, there was nowhere to meet. Gerchman took over Parque Lage and transformed it into an island, a garden of opposition. It was a place where everyone was allowed to talk; they could meet, they could believe, and they could express themselves freely, and Rubens was daring, he didn’t let the police enter, he defended the place tooth and nail.”4

Gerchman's project for the EAV could have been threatened, censored and even closed down in the context of the repression in which the country found itself under the military regime, but the school managed to remain a space for cultural resistance.

The Experience at the Bowery

The “Pedagogy of Everyday,” which Gerchman would introduce at the Parque Lage school, was intrinsically linked to the period during which he lived in New York, from 1969 to 1972. As the winner of the National Salon of Modern Art award, he traveled to Manhattan with his wife, the artist Anna Maria Maiolino, and their two children, supported by a modest monthly scholarship of five hundred dollars. The couple's apartment at 250 Bowery Street, on the Lower East Side, later became a reference point for Brazilians passing through the city, such as Lygia Clark, Sérgio Camargo, Glauber Rocha, Antonio Dias, Amílcar de Castro, Ivan Freitas, and Roberto De Lamônica, among others.

The neighborhood, which was then inhabited by homeless people and drunks, has now been completely gentrified. For anyone visiting the imposing International Center of Photography (ICP), accross the New Museum, on the Lower East Side, it is impossible to imagine that this is where Gerchman lived with his family. Oiticica described the neighborhood in a letter to Lygia Clark: “The first time I went there, I thought I was entering a scene from Bosch: a thousand bodies in the street, with urine, blood, wounds, garbage, empty bottles everywhere, people begging for money, etc.”6 In that same neighborhood, there were also Latin American artists who in the 1970s were looking for a cheap place to live in the city. Most of them, like Gerchman and Maiolino, were self-exiled artists, who were not necessarily being politically persecuted, but who were at odds with the repressive climate of Latin America.

Until then, Paris had been the most popular destination for Brazilian artists and intellectuals. The ambivalent attitudes of the time towards the United States, one of the main counterculture centers, but also one of the greatest allies of the Brazilian military regime, made it a daring option.7 Gerchman already had a solid artistic career in Brazil, with market recognition and participation in major exhibitions in museums and galleries.8 This privileged situation did not replicate in New York.

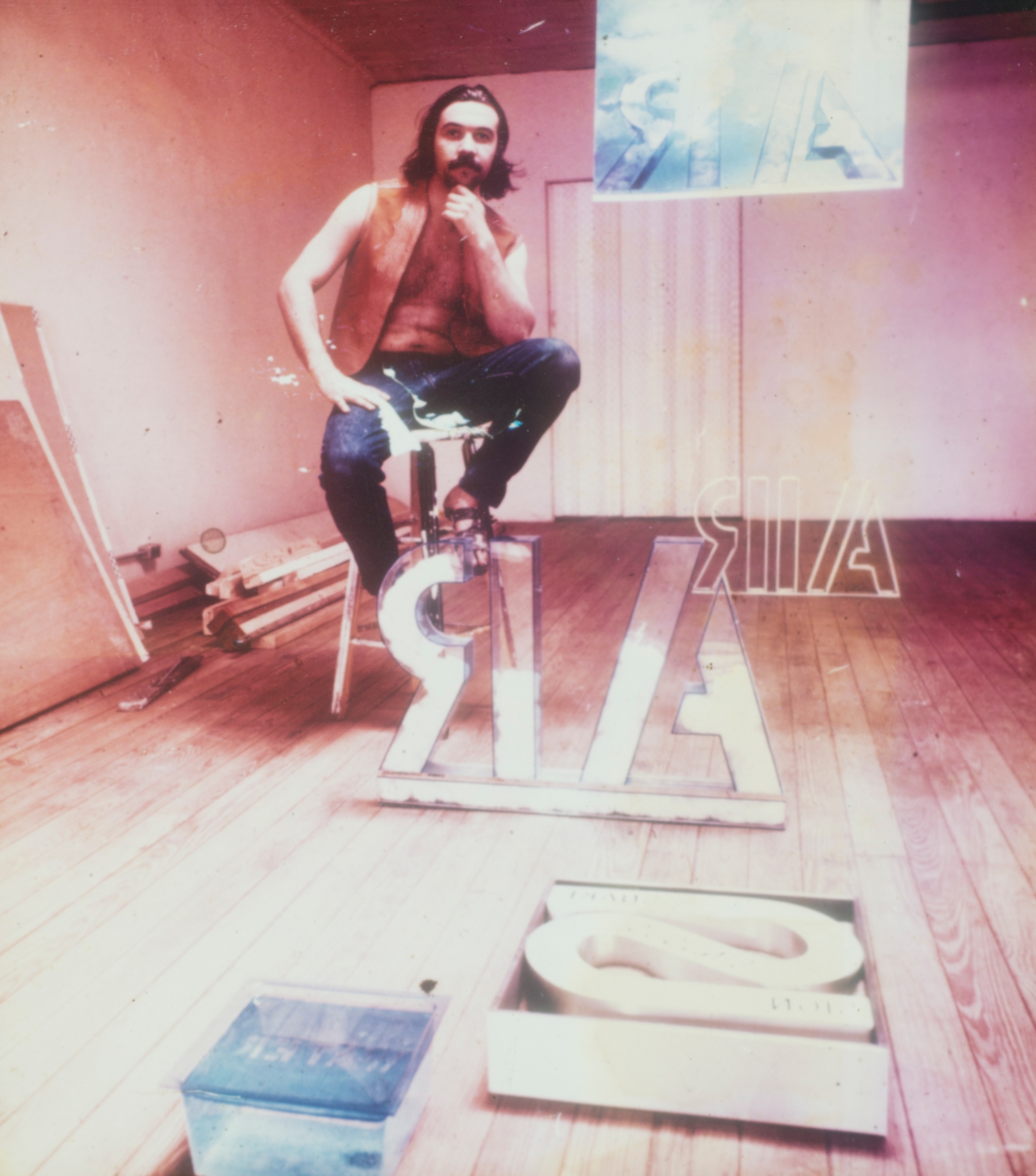

Disembarking from a cargo ship and living as a Latin American artist in the great metropolis, the daily reality of Gerchman’s existence would be very different. Penniless and struggling to find suitable materials with which to work, Gerchman began to produce small works, acrylic boxes with English words like “sky/color/blood/sun/herb,” thereby creating a kind of poetry/object.9 The accelerated pace of the city, the emphasis on art as a marketable product, the pragmatism that defined relationships, all these factors would contribute to Gerchman's new artistic production, which began to acquire a more compact character, devoid of excess. The grandiose and monumentality of his work became synthesized and condensed.

Conceived while the artist was still living in Rio de Janeiro, the gigantic words of the Cartilha do superlativo (Superlative Booklet)10 were down-sized to pocket poems during his time in New York. Oiticica named them Pocket Stuff, and later described them as “a proposition for a constant act of carrying.”11 During a train trip, Oiticica lived a magical experience through the poem/object “Sky.” Contained within a small blue box and covered by a clear acrylic lid, the word/object “sky” spills out into the space beyond the box. Through this semantic/spatial game, Gerchman addressed concrete poetry and the experiential propositions of Neo-concretism.

In early 1970s New York, conceptual art was establishing itself as the new trend, replacing the excessive imagery of pop art and the emphasis on materiality advocated by the minimalist movement. The image came to be seen as language, art itself as an idea and reflexive proposal, rather than a purely visual experience. The art critic Wilson Coutinho considered that, by working with conceptual practices through words and their semantic connections, “[Gerchman] assembles his bricolage; he wages a battle against the image, which forces him to practically extirpate the sensorial and intellectual aspects of painting or drawing, considered a failed media.”12 Commenting on the direction that Gerchman's work was taking, Oiticica stated:

«What interests me about this evolution by Gerchman is precisely the progress from an age of the superlative image to the formalization of a synthesis that is required today. In Brazil, the idolatry of the image reaches a level of redundancy and descends into a dangerous morass; there is a kind of exercise of the power of the image, but that does not lead to transformations and it tends to be converted into an aestheticism, or into an all-encompassing anecdote.»[13]

Gerchman was already living in New York when Oiticica arrived in the city, towards the end of 1970, traveling from London, where he had exhibited The Whitechapel Experience at the Whitechapel Gallery (February-April, 1969)14. As part of that show, Oiticica created the Eden installation, a space where the visitor walked through delimited areas containing straw and sand, experiencing a variety of sensations. At the end of the exhibition, there were the Ninhos [Nests], wooden boxes forming a rectangle, with divisions lined with straw, where the participant could finally curl up and nest: playing, sleeping, listening to music, and wrapping themselves up using materials of different textures.15

Oiticica developed the notion of Crelazer (a combination of the Portuguese crer — believing —, criar — creating — and lazer — leisure). The idea was to combine work and leisure, not as a passive attitude, but as an agent of transformation. According to Oiticica: “[I] invented a thing called Crelazer, I wanted to transform the day in its entirety, including leisure and laziness, into something like a permanent inventive state, that's why I started to transform the place where I live, that was the ideal, to live in the work itself.”16

Oiticica transformed his living space at 81 Second Avenue in the East Village, just a few blocks from the apartment where Gerchman and Maiolino lived, into a big “Nest”. The “Babylonest,”17 as it was called, was described by the concrete poet Décio Pignatari: “In his house, around a bunk bed, he installed a penetrable space in the form of a parangolé nest, a labyrinthine bricolage web with collages, augmented by all the informational paraphernalia he had at his fingertips, from pencils to files, from the record player to the television set, one always on, the other turned off, and with phrases and slogans covering the ceiling.”18

The coexistence with Oiticica, as well as the concept of Crelazer, played a decisive role in the “Pedagogy of Everyday” that Gerchman would implement a few years later at the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts. The combination of work, leisure and pleasure would be one of the driving forces behind his educational practice. Gerchman transformed Parque Lage into a huge space for Crelazer, using not only the school but also the surrounding gardens, and transforming the place into a great cultural center, in the heart of Rio de Janeiro.

Create at Leisure: Crelazer and the Black Mountain College

In New York, Gerchman also worked with the Uruguayan conceptual artist Luis Camnitzer, for whom art was above all a pedagogical tool, a way of acquiring and expanding knowledge. For Camnitzer, art was a problem to be solved, and process and ideas took precedence over the object.19

Together with Camnitzer, Gerchman contributed to the Latin American Museum created in 1969 by a group of Latin American artists residing in New York — including César Paternosto, Luis Wells, Omar Rayo, and Liliana Porter, among others — to protest against the policy of supporting military dictatorships in Latin America, and led by some of the key members of the Center for Inter-American Relations (now known as the Americas Society). Together with Wells and Camnitzer, Gerchman created the Integralia Corporation, a short-lived company that developed a variety of art projects, including Pocket Stuff.

Despite not having participated directly in the New York Graphic Workshop (NYGW), --founded by Camnitzer, José Guillermo Castillo, and Liliana Porter--Gerchman was conscious of this important milestone in the history of Latin American art in New York.20 During its short existence, from 1964 to 1970, the mission of the NYGW was to redefine the practice of printmaking, in conceptual and artistic terms, in opposition to its traditional emphasis on technique. The Workshop was established as a space to promote the exchange of ideas among artists, and to serve as a collective center for teaching, exhibiting and experimentation professional printmaking.21 The idea was to connect art to the day by day.

Oiticica also explored the use of art as a pedagogical tool during his time in New York, when he produced the workshop “Experimentaction” (combining the words ‘experiment’ and ‘action’) at the 92nd Street Y cultural space, on the Upper East Side (from October 1972 to January 1973). The aim of this “anti-course” was to stimulate the sensory perception of materials, the construction of spaces (labyrinths, rooms, nests), and collective participation. Oiticica transmitted his conceptual ideas through practical orientation, such as the perception of the body in space, the making of coverings for the body, proposals for games, visits to locations beyond the classroom, the building of “nests”, exercises with everyday objects, the sharing of experiences among artists, the production of public performance, the attention to colors and the proposition for a class in which individuals could offer their own proposals.22

Bringing together the educational practices and concepts of Camnitzer and Oiticica, the "Pedagogy of Everyday" implemented by Gerchman at the EAV also had a solid influence by the educational model developed at Black Mountain College (1933-1957), an artistic community that broke down the barriers between art and life, and which is considered the cradle of avant-garde experiences in the United States. This legendary school became famous for the spirit of collaboration between artists, the atmosphere of experimentation, the disregard for student-teacher hierarchies, and a teaching method based on improvisation and a playful approach to the creative process. The school based its method on an interdisciplinary approach, with an emphasis on intellectual questioning, discussion and experimentation. The idea was to provide an education centered on the liberal arts, based on the pedagogical and progressive ideas of the philosopher/educator John Dewey, with the aim of giving students a holistic training, as individuals and citizens.23 The school advocated the dissolution of the hierarchy that placed the visual arts above other artistic practices such as crafts, ceramics, architecture, poetry, music, theater and dance. Art was seen as a process and not as a final product.

It was there that John Cage developed experimental music, Merce Cunningham formed his dance company, Allan Kaprow exhibited his first happenings, and Josef Albers taught his theories of perception. Others students included Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Kenneth Noland, and many others.24 Arriving at Black Mountain College, one student asked Josef Albers what he was going to teach. The answer was clear and unequivocal: “How to open your eyes.”25

From Bauhaus to Parque Lage: from Technique to Action

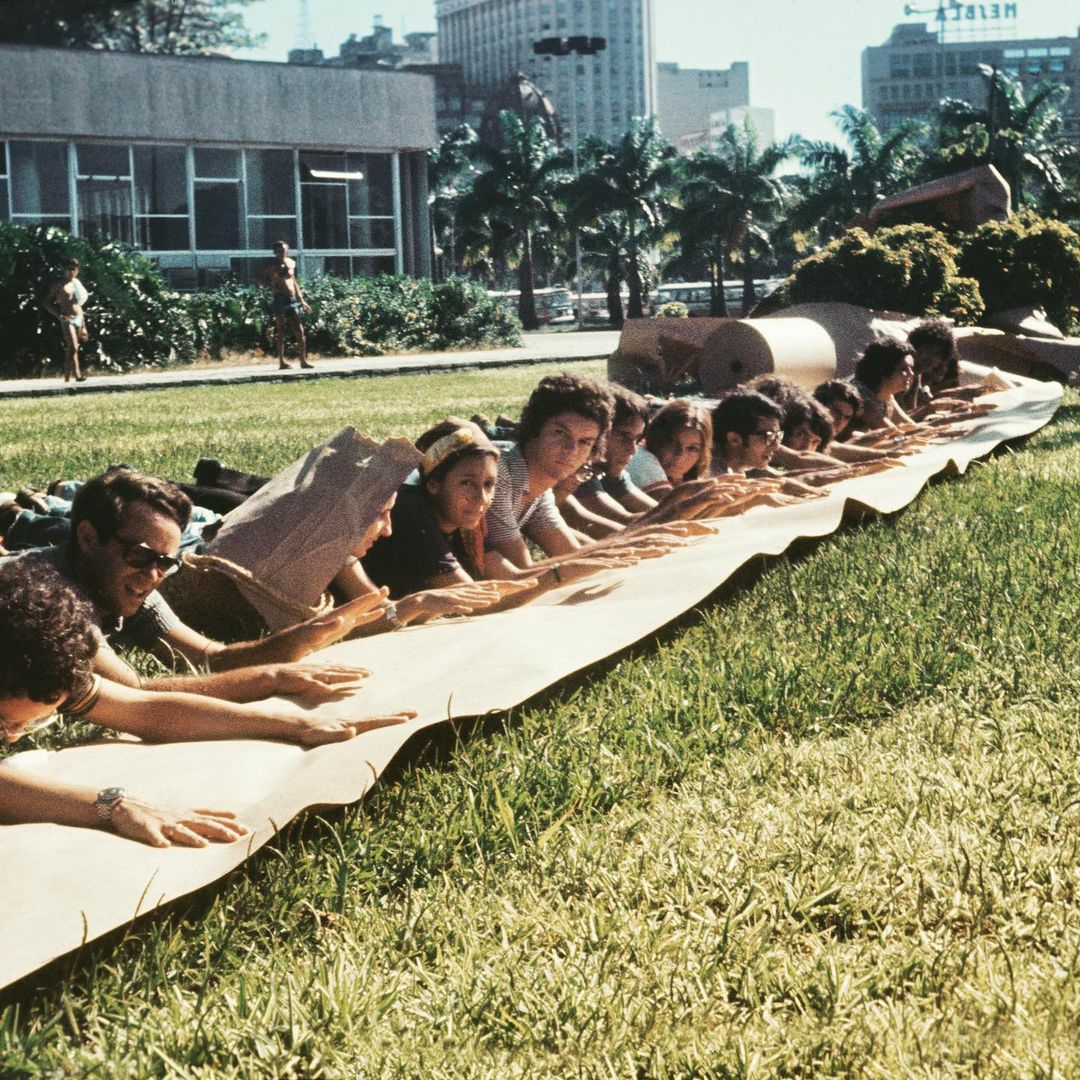

The experimental pedagogy of Black Mountain College was incorporated into the “Oficina do Cotidiano” (Day to Day Workshop), created by Gerchman at the EAV to teach the 2D (two-dimensional) course. Upon arriving at the workshop, students were invited to open their bags and backpacks to show what they considered necessary to carry with them in their day-to-day lives. They were also encouraged to use materials collected on the street, on the bus, on the beach; investigate the use of newspapers and magazines, and bring to the classroom narratives of family episodes, and stories related to their own love lives.

Gerchman and his students painted on media spread out on the floor, with little formality. They used everyday, cheap, accessible and precarious materials. Gerchman encouraged participants to take risks and to believe in the creative process in the making of art, without compromise. With no authority figures or templates, students were free to experiment. They could attend as many workshops as they wanted. They were allowed to sign up for one class and attend as many as they wanted. If necessary, they could also sleep at the institute.26 The set designer Helio Eichbauer recalled the school as a Dionysian experience:

«I gave many classes outdoors and on the terrace. On the terrace, even though there were so many great bathrooms, after working the people would bathe with buckets and hosepipes, they’d wash with a hosepipe and they loved doing it, and all in the morning, and the swimming pool, and so it was a moment that seemed crazy for that time, it was like a big feast of Bacchus, it seemed bacchanalian, it was bacchanalian, but it was also a school where you learned a lot, you studied a lot. But this is what I think. I believe that the right way to teach in the contemporary world is this, it has to be done with joy, with fun, with music, with great passion».[27]

When Gerchman was invited by the dramatist Paulo Afonso Grisolli (1934-2004)28, the director of the Department of Culture of the Secretariat of Education of Rio de Janeiro, to direct what was known then as the Institute of Fine Arts, he knew that it would be a great challenge, not only because of the difficulty he would have to face in implementing an experimental teaching method, but also because of the censorship imposed by the military regime. The story is well known of how, as Gerchman hesitated, he was encouraged to accept the post by the architect Lina Bo Bardi, who told him: “Accept! And if you feel you should leave, then resign.”29

From a meeting between Eichbauer, Bo Bardi and Gerchman, a free and democratic school, a gathering place for young and old people, artists, and the community of Rio de Janeiro, began to take shape.30 Bo Bardi and Eichbauer were responsible for the “Oficina Pluridimensional” (Multidimensional Workshop), an experience that brought together into the space dance, stage designs, painting, and body art.

Bo Bardi and her husband, Pietro Maria Bardi, had already tried to create an art school, the Institute of Contemporary Art of the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art (IAC). Inspired by the Bauhaus (1919-1933) and based on the curriculum developed by the concrete artist Max Bill for the Ulm School in Germany (1953-1968).,the goal of the IAC was to train designers for the rapid industrial growth being experienced by São Paulo.31

In Rio de Janeiro, the drive to create an art school based on the principles of the Bauhaus and the Ulm School resulted in the founding of the Higher School of Industrial Design (ESDI), in 1963. Although the ESDI was created with the aim of establishing an industry-focused design school, a very different educational initiative later took shape at the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art (MAM-RJ). The MAM-RJ School of Art, which had been founded in the 1950s, took on a new impetus when the art critic and curator Frederico Morais took over the coordination of the courses between 1969 and 1973. Under Morais' leadership, the school went through an important restructuring, incorporating its surroundings, the Parque Aterro do Flamengo, as if it were an extension of the museum.32 The museum's cafeteria became a meeting place for artists, turning the MAM-RJ into a great nucleus for the visual arts. According to the art historian Adele Nelson, “the MAM student was not the designer of posters and products, but an artist with a brush in hand.”33 Undoubtedly, the MAM-RJ School of Art constituted the embryo of the future project that Gerchman would implement in the EAV. But with all its innovations, the museum was still a space dedicated mainly to the visual arts, or to the filmgoers who frequented its movie theater, and above all it was an institution dedicated to the mounting of art exhibitions. The confluence of different tribes only came about with the founding of the EAV in 1975.34 Following the fire at the MAM-RJ in 1978, the EAV began to play an even more important role, as a place of resistance and mobilization.35

In the different testimonies provided by the protagonists of the time, what is most striking is the passionate character that Gerchman introduced to the EAV. The effervescence, the vitality that the school possessed at that time, as well as the multiple activities conducted simultaneously, were among the most notable legacies left by Gerchman. With his restless and innovative spirit, he created one of the most active cultural spaces in the country; an open and experimental space for all artistic practices.

The EAV played a fundamental role as a place where Brazil’s most active artists, musicians and thinkers could meet and exchange. Rather than visual artists with brush in hand, the EAV created citizens willing to think, discuss and create. If Gerchman taught anything, it was that there is nothing extraordinary about the teaching process. To create great works and ideas, it is necessary to address the banal and the ordinary, and allow oneself to be motivated by the endlessly surprising lessons of everyday life.