Lygia Pape, Professor: Pedagogical Practices as Artistic Practices

06/13/2022

Defining herself as "intrinsically an anarchist," her pedagogical practices followed the same direction: they vindicated unrestricted freedom for creation and were based on a "deconditioning" of teaching towards entering "states of invention."

This essay encompasses notes on the teaching realizations of Lygia Pape (1927-2004), which took place at the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro - MAM-RJ (1969-1971), the Department of Architecture at the Universidade Santa Úrsula (1972-1985), the Escola de Artes Visuais Parque Lage - EAV (1976-1977), and the Escola de Belas Artes at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro - EBA / UFRJ (1981-1999).

In this context, the TEIA project, developed with students in the forest of the Escola de Artes Visuais Parque Lage in the late 1970s, comes up to contribute to the debate, in order to explore experiments on nonlinear forms of participation, collaboration, and collective action. On the basis of 'TEIAR' [to web or weave] and 'the new principle of moving upward or downward, to and from: without the harm of a single point of view,' there is a starting point for the modes of co-creation in the radical experimental convergence between the artistic practice and the pedagogical practice of Lygia Pape.

Radical-Experimental-Ambivalent-Free

Lygia Pape's teaching practice, which began in the late 1960s and developed over decades in different contexts—courses in museums, in experimental schools, in private and public universities—is intrinsic to her artistic practice. The intentions and realizations linked to her teaching experiences—a side that has been little researched among her many professional activities—are found, though occasionally, in recent publications that bring together interviews, testimonies, and writings of the artist. And it is based on these materials that I write these notes, still brief, about Lygia Pape, the professor: pedagogical practices as artistic practices and/or modes of joint creation.1 In the lexicon that makes up the artist’s plural practices, the words 'radical,' 'experimental,' 'ambivalent,' and 'free' stand out.

In 1969, Lygia Pape debuted as an educator, teaching courses in the Departmento de Artes Plásticas at the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ). In 1971, the artist Anna Bella Geiger (1933) invited Lygia Pape and Antônio Manuel (1947) to teach in the experimental course 'Activity/Creativity,' an integral module of the MAM-RJ educational program that was carried out next to the museum. Outside the classroom, the experimental activities aimed to establish a "community of creation with the students.”2

The term 'activity/creativity' was proposed by Lygia Pape as an homage to art critic and friend Mário Pedrosa3 (1900-1981). Used as a form of induction to the art practice, without the aim of creating a single object or a specific category, the course was based on initiations in which each one used their experience, setting out from the suggestion of a collective production made with the available materials.4 According to Anna Bella Geiger, "the purpose was precisely not to have any mystery about a course that should lead to the creation of an art object. It was the awareness of the very meaning of freedom."5 Concerning the classes of that period, in an interview conducted in 2003, Lygia Pape recalls having worked on that occasion with sounds and forms, exploring words that implied physical situations, merging sound, rhythm, and image of the word.6

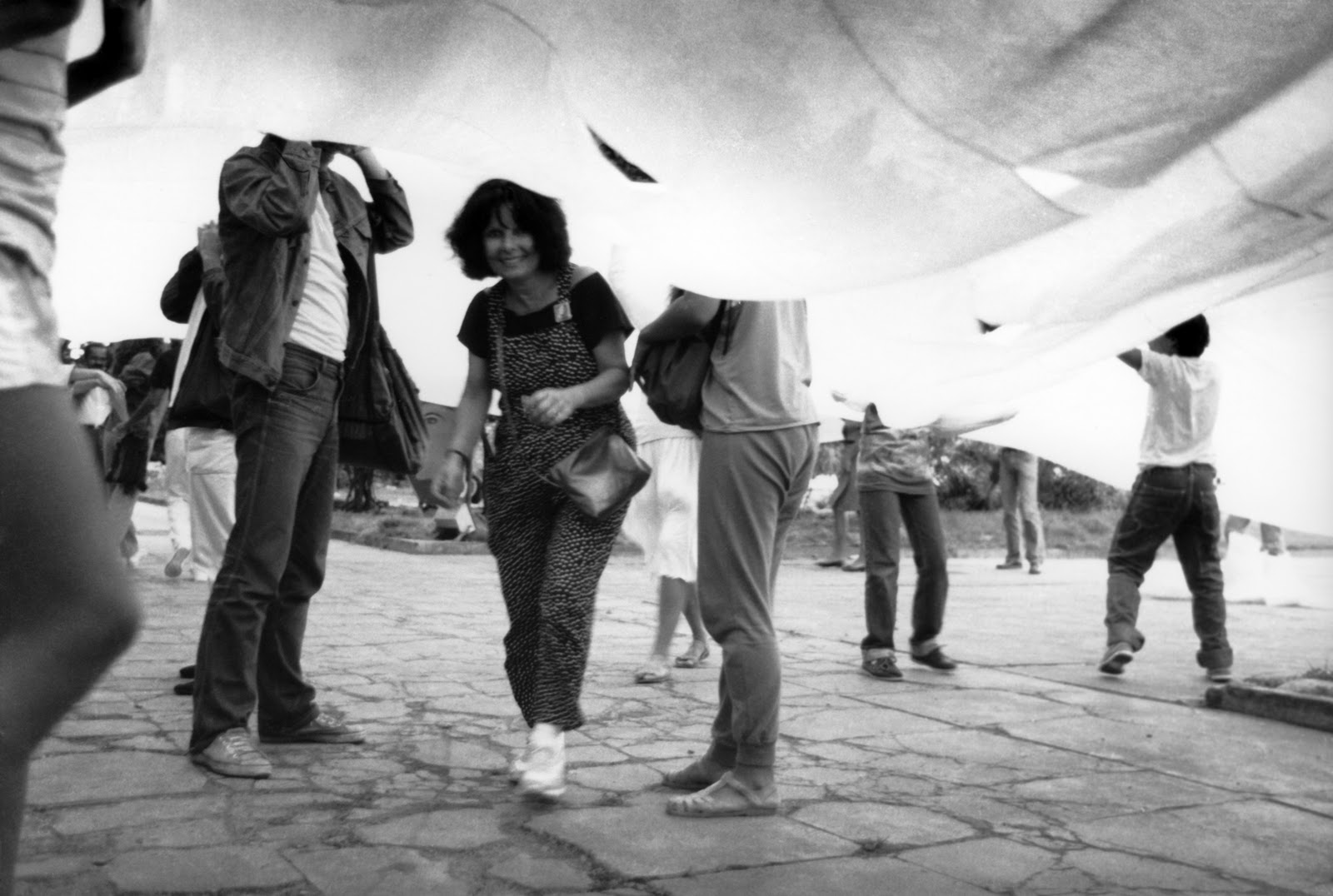

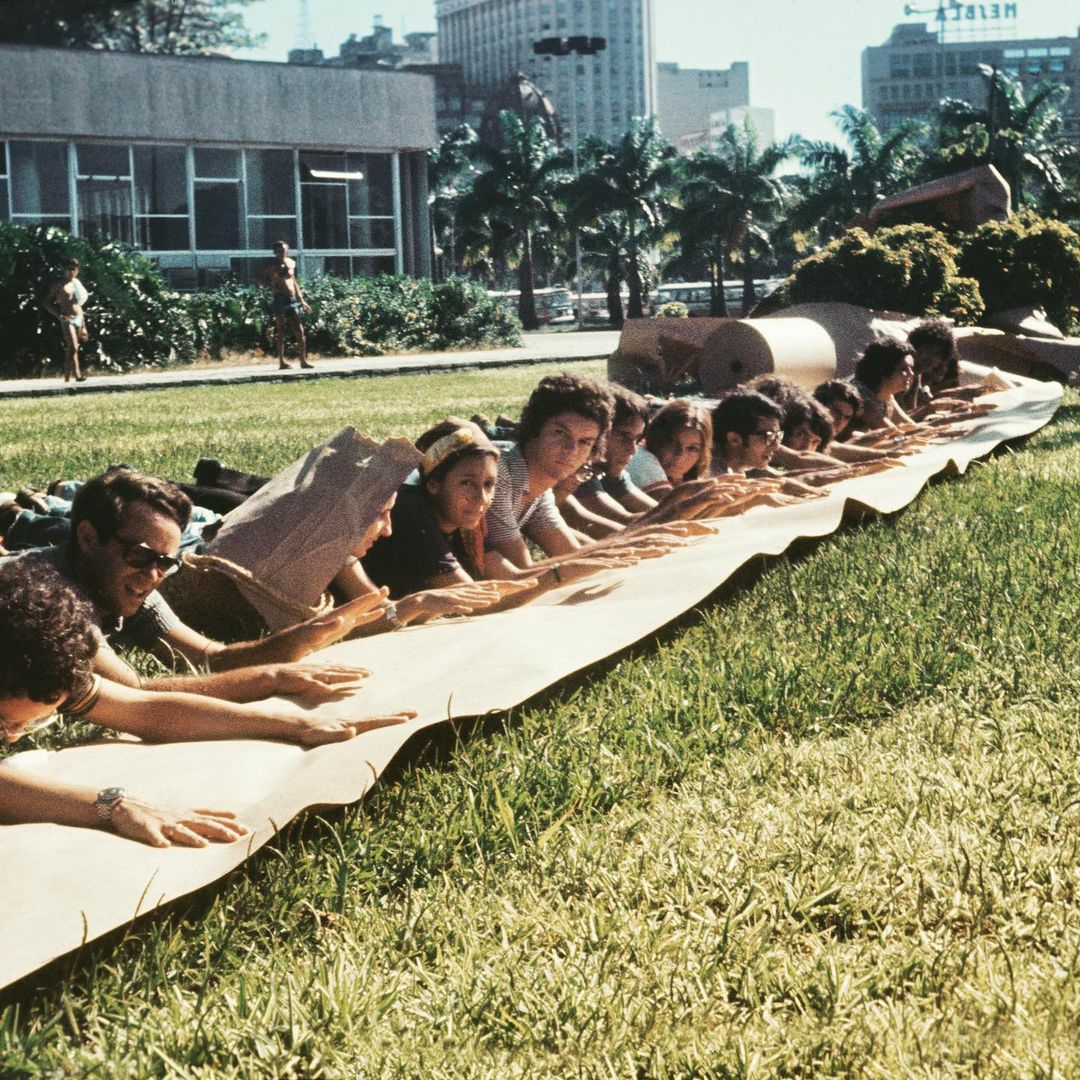

Also in 1971, the artist participated in the first session of 'Domingos da Criação' [Sundays of Creation], proposed by Frederico Morais (1936) in the outdoor area of the MAM-RJ, where on the last Sunday of each month, between January and July, different artists invited the public to participate with diverse materials donated by industries and made available for free creativity exercises.7 In this series of artistic-pedagogical-participatory events that became iconic for bringing together exponents of the Brazilian experimental artistic production of the time, Lygia Pape proposed for the first iteration—'O domingo de papel' [Paper Sunday]—the work 'paper pool': a literal immersion into shredded paper inside the museum's outdoor pool. "In the creative making, everyone gets confounded," said Frederico Morais about this set of actions.8

In 1972, the same year she received her bachelor's degree in Philosophy from the Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Lygia Pape started teaching at the Centro de Arquitetura e Artes of the Universidade Santa Úrsula, in Rio de Janeiro, a private institution where she worked until 1985, teaching her 'anti-classes'—a term she used to define her classes.9

With humor, she claimed that her anti-classes in the Architecture course were an antidote for the conventionalism of other subjects in the curriculum.10 Defining herself as "intrinsically an anarchist,"11 her pedagogical practices followed the same direction: they vindicated unrestricted freedom for creation and were based on a "deconditioning" of teaching towards entering "states of invention."

In words of her close friend Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980), experimentation depended on a process of 'deconditioning,' that is, on the “overthrow of all conditioning for the pursuit of individual freedom.”12 To enter such 'states of invention'—also borrowing the term coined by Hélio Oiticica—it is the artist’s function to encourage and lead the 'former spectator' participant in overcoming the hierarchical distinctions to “make each person enter into the state of invention and from there a collectivity can emerge.”13

In her anti-classes, students' testimonies recall realizations as practical exercises consisting of building objects—raising brick walls, for example—and (re)creating new meanings for everyday objects. To grow awareness of the ordinary actions that are carried day-to-day, Lygia Pape proposed attention exercises such as, for instance, describing the path traveled to reach the university, intending to evoke an internal (re)cognition of the self-contained potentialities for building experiences and records in the simultaneous perception of the city’s spaces.

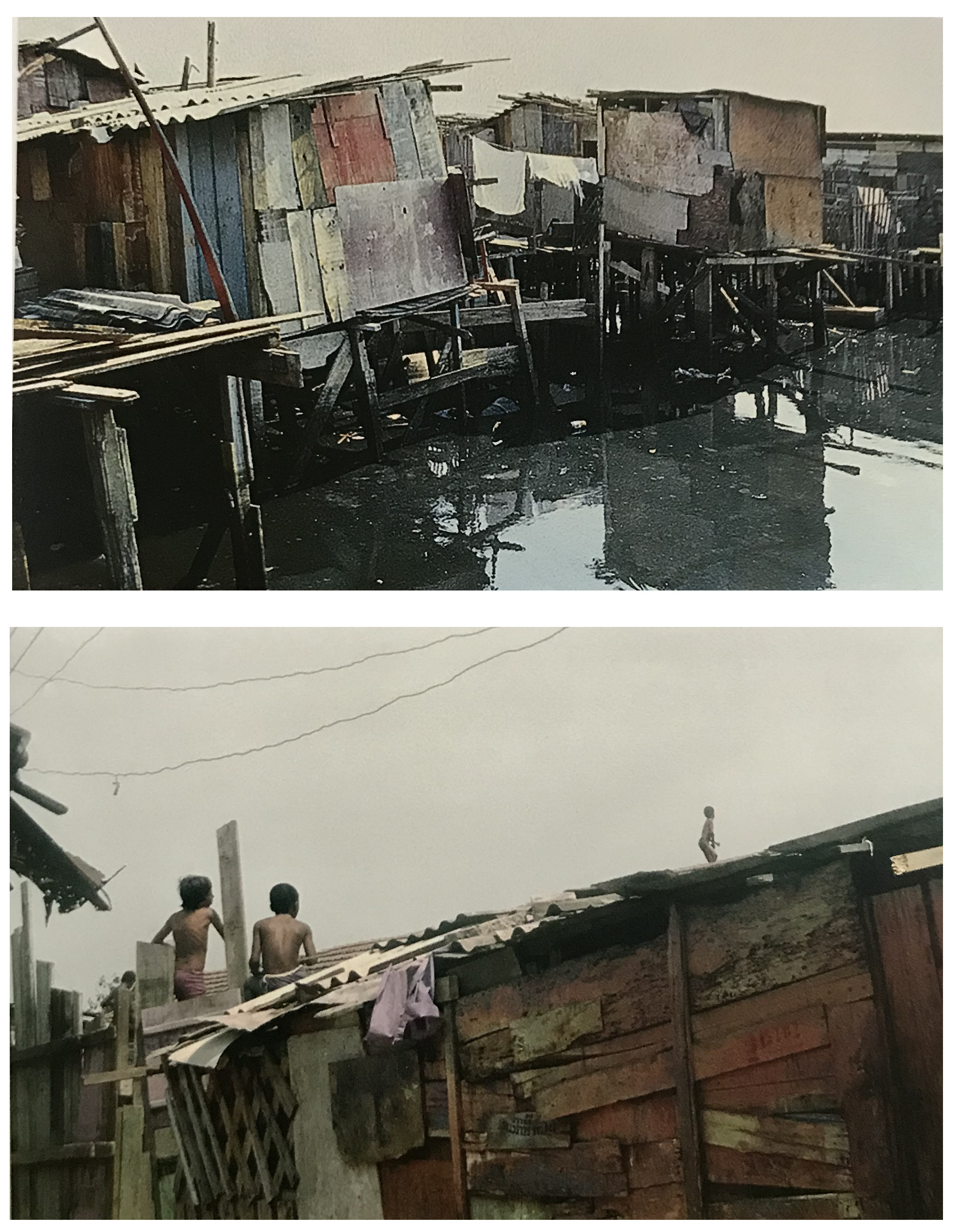

"How could you be a good architect if you didn't even know Rio de Janeiro?"14 asks Lygia Pape in proposing ‘incursions’ with her students to the Favela da Maré, one of the largest community complexes, located in the north of Rio de Janeiro.

In 1972, the artist wrote the text "Favela da Maré ou Milagre das Palafitas”15 [Favela da Maré or Miracle on Stilts] and, in the same year, she made Favela da Maré, a ten-minute-long super 8 film.16 In the text, Lygia Pape professes her fascination for seeing and thinking about the diversity of inventions in popular constructions. "At the time, my intention with my work and my classes appears intensified with external and direct experiences of interpreting the world (...)"17. In the film, she documents the register-path made from 'back to front': in the mobile labyrinth of the community complex, with people entering backwards into the frame in a continuous flow, without inside nor outside, into the Moebius Strip—a metaphor often evoked by the artist. "Lygia Pape, like Hélio Oiticica, sees 'solutions' in spaces of popular housing, as well as the invention of an aesthetics of the precarious, the transformation of the most hostile forms into creative potential," asserts Ivana Bentes in an analysis of the artist's film production.18 During her ‘incursions’ into the Favela da Maré, Lygia Pape also takes hundreds of color photographs that explore architectural details of the houses, entrances, rooms, living rooms, inhabitants of the community complex.

In the contemporary context, could the pedagogical-artistic practice of making ‘incursions’ into the Maré complex proposed by Lygia Pape be read as an extractivist-exploratory action of the 'aesthetics of the precarious'?19 On the one hand, there is an experimental practice of territorial (re)recognition of the city carried out in the context of the 70s, during the civic-military dictatorship in Brazil, within an Architecture course at a private university in Rio de Janeiro, that was essentially elitist and guided by formalist-modernist teaching, which was assumed as transgressive.20 On the other hand, presently, there are recent decolonial approaches that also question the processes of internal colonization as well, where the practices of extracting the value of 'difference'—which occurs even in visual arts—are a core part of this regime and are not exempt from later problematizing.

In the context of the 70s, both Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica evoke the word 'ambivalence' as a reading key to their works. "This plastic concept is the translation of a refusal to work with any notion of hierarchy in art. This is what allows me to transgress the nature of things," says Lygia Pape.21 To assume and recognize ambivalences, says Hélio Oiticica, warning of the urgent and permanent need for taking a critical standpoint and affirming the experimental in the face of the Brazilian paternal-cultural form.22 Today, in the 21st century, amid canceled cultures and canonizations, questions remain open about what is ambivalent and what is antagonistic in pedagogical-artistic practices.

In the light (or in the shadows) of the persistent modern dichotomies that continue to resonate between discourse and practice, the syllabus of one of Lygia Pape's anti-classes taught in the Architecture course at the Universidade Santa Úrsula points to convergence. "Objective: To give students proposals of behavior aiming at an open structure methodology. This behavior could be translated as the ability to know how to think creatively, that is, to think actively, transforming the information received or perceived into something personal and new. To awaken, in a majeutic way, the student’s creative potential. The process employed will be, first of all, handling all of the student’s senses, not only the visual—the student as a creative whole. The visual, in the specific case of the subject, would be the student himself plus all the other senses. The grasping of reality would become an experimental exercise in creative freedom."23

In 1976, in a room adjacent to her first major solo exhibition Eat Me: A gula ou a luxúria? [Eat me: Gluttony or Lust?], held at the MAM-RJ, Lygia Pape proposed the exhibition Espaço: Comentário [Space: Commentary], a space dedicated to showing the individual works of her assistants and students of the School of Architecture at the Universidade Santa Úrsula. On the gesture and the exhibition space dedicated to the teaching practices, the artist reflects: "incorporating students and students’ activities as a work as well, a work of art inside the MAM, the Museu de Arte Moderna, because there, at that moment, I broke with a tradition of the architecture course, of the courses, in general; to the extent that I called up the students and opened up space for them to do whatever they wanted, I was already making a new, different connotation."24 The experimental exercise in creative freedom is applied to the institutional exhibition context.

SPIDERS, SPIDER WEBBING, COBWEBS

In the years 1978-79, as part of the 'Espaços Poéticos' [Poetic Spaces] course and in collaboration with artists who were her students, Lygia Pape—also a professor at the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts (EAV)—carried out the TEIA project in the forest where the EAV is located.

"Tteia. Área aberta" [Tteia. Open Area] is a text written by the artist in 1979, describing the intentions and achievements of this proposal and it is also a key text to expanding the lexicon that makes up the plural practices proposed by Lygia Pape together with and through collective-collaborative pacts.25

«The "TEIA" [COBWEB26] project aims to occupy areas of the city of Rio (southern zone) and mainly of the northern zone, that is, the so-called "Baixada Fluminense," with a collective movement where the structural installation is completed with citizen participation. The proposal is to "weave the space" in a process of creativity that establishes a new relationship between the creator of the project and the audience, who must appropriate it and also claim the uses that could take place in it, throughout and after the presentation. The fundamental idea is to profane the art object, or to eliminate authorship from the beginning. Despite having an author, the installation can be carried out by anyone, as long as there is a WILL, because it is not intended as a "special touch" but as a level of expanding new perceptions from the new horizons arising or being generated from the estrutura-TEIA [COBWEB-structure]. I also intend to start with only one thread, nothing more; the installation will emerge, growing in its own place of use. Before, there was nothing, and afterward, only the idea and perceptions generated by the ARANHADA [SPIDER WEBBING] will also remain.»

It is the act of 'weaving' that originates what Lygia Pape calls “ESPAÇOS IMANTADOS” [MAGNETIZED SPACES]: "well-defined, even geographically, threshold situations in which special poetic things are happening." For the artist, certain structures—"TEIA" [COBWEB]—can be only visual, while others can be used to go up or down, altering the "principle-of-the-horizon-line."

«The "TEIA" [COBWEB] will allow for altering the relationship of the viewer with his being in the world, [not] from a single point of view but from different points of view and heights. The "TEIA" [COBWEB] can modify this relationship: in the spider-man. This mechanics will be called ARANHADAS [SPIDER WEBBING]: rising in the air, held only by a light torn fabric, pierced by light, like colored filaments of his own thread-structure. "TEIAR" [to web or weave]—is the new principle of moving upward or downward, from one side to the other: without the harm of a single point of view. This new appreciation of space and objects leads to a heightened perception of the eye and also of the entire body: gliding from top to bottom has so far been the privilege of birds alone.»

With this project, the artist sought to experiment with non-linear forms of participation, collaboration, collective action, and a way of co-creation. Evidencing, in turn, the intention to profane the work of art and to dissolve authorship—even if an author does exist—as Lygia Pape points out.

Being the artist some kind of spider and the city a huge entanglement,27 the links between the two are also reinforced by the research grants received by Lygia Pape; among them are: 'Poetic Spaces: An Architecture of the Precarious' (1975) to continue with the documentary photographs made in the Favela da Maré in her 'incursions' with students; 'Woman in Mass Iconography' (1977), a research grant from the Fundação Nacional de Arte (FUNARTE); 'Indigenous Architecture and Favelas of Brazil,' Guggenheim Fellowship; and the research grant 'Architectural Education in Rio de Janeiro' (1988), awarded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). In the same year of 1988, as part of the UNESCO World Conference on Education, Lygia Pape also organized the lecture 'Architecture and Creativity in the Favela da Maré' at the Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ).

The Escola de Belas Artes of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (EBA/UFRJ) is the last institution where Lygia Pape teaches. Having entered in 1981 through public tender, her performance in the Visual Languages research area, at the Art History Master’s Program, was decisive for the creation of the Visual Arts post-graduate program.

Regarding the collection of practices employed by the artist, testimonies of former students emerge: "What Lygia Pape did was to ignite sparks, as poetic triggers that set off processes—artistic, sensitive, reflective—in/of the other, never by the other," said Nélson Félix (1954).28 "She speculated to see where you swayed. She would ask, "What are you doing?" Then she would stick her finger in the wound. Who left me this viscerality, who taught me to use the stomach, was Lygia Pape," recorded Ronald Duarte (1963).

"Everything I do in art, I do in life," declared the artist.29 With teaching, it would be no different. Creative freedom, in all spheres, is a great lesson from Lygia Pape's anti-classes for art pedagogies in the twenty-first century.