From the Edge of the Edge: A Crossover Between Pedagogical and Curatorial Practices

03/29/2023

by Lara Marmor

The artistic, pedagogical and curatorial practices of Alberto Goldenstein, Fernanda Laguna and Roberto Echen generated new ways of perceiving and understanding part of the world [...] What fights they had to face? What traces they left? Why they marked an era?

The artistic, pedagogical and curatorial practices of Alberto Goldenstein (Buenos Aires, 1951), Fernanda Laguna (Buenos Aires, 1972) and Roberto Echen (Santa Fe, Argentina, 1957) generated new ways of perceiving and understanding part of the world: that of artistic production. They built aesthetic, intellectual and operative strategies to give rise to works and experiences that had no place within the Argentine art system until their gaze put them on stage. They made a difference in relation to what was happening as they knew how to grasp the present and its urgencies, they promoted instability and disruption by opening transformative spaces in the field of education and curatorship in a fluctuating process between both spheres.

The trio is part of a larger group of agents whose common denominator is having changed part of the visual arts map at the end of the 20th century, and whose effects are noticeable in what we have traveled through the 21st century.

A group that wanted to do through the exercise of teaching, curatorship; what fights they had to face? What traces did they leave? Why they marked an era? These are some of the questions whose answers, hopefully, can guide the understanding of the artistic dynamics in the cities of Buenos Aires and Rosario, an industrial and cultural center in the southern part of the Santa Fe province.

Desprejuice

In Alberto Goldenstein's work production, teaching and curatorship feed back into a chain of transitive desires and needs. We will begin with his curatorial work at the Fotogalería del Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas (FGCCRR), founded by the artist in 1995 in which he remained without interruption until 2013. The beginnings of this space can be traced back to 1991, when at the request of artist Jorge Gumier Maier, within the framework of the opening of the Visual Arts Department of the Ricardo Rojas Cultural Center (CCRR), he started the Photographic Image Workshop. The pedagogical premises there would be found in direct relation to the work of his curatorial future. "It doesn't even occur to me to correct photography. I try to understand what the artist or the student is doing and, in any case, there are times when I can see some way to enhance their intention (...) I think the most important thing I can do is to accompany them to get lost (...) While taking pictures, they feel they have to have a theme, a coherence, a technique, a lot of things. I accompany them to let go and then pick up those pieces."1 In both spaces, the photographer postulated the indistinction between good and bad, a functional dichotomy to differentiate the aesthetic quality of a good photo from a bad one, within the framework of a language where technical expertise historically occupied a fundamental place. Both in his classes (which he continues today but in his own studio) and in the Fotogalería, Goldenstein vindicated error and imperfection as antonomasia to what was considered a norm.

As an artist, in 1991 Goldenstein presented Fotografías de Alberto Goldenstein, his first solo exhibition at the FotoEspacio of the Centro Cultural Ciudad de Buenos Aires; in 1997 he exhibited El mundo del arte - vacaciones at the Fotogalería of the Teatro San Martín and in 1998 he exhibited Fotografías de Alberto Goldenstein at the Fotoclub. Until 1999, with the exception of the Rojas Gallery,2 his work had only been exhibited in galleries dedicated exclusively to photography. This initiatory exhibition tour seeks to highlight the functioning of the art circuit in Buenos Aires: photography was not mixed with other languages, it was not understood as art, it was encapsulated, it lacked a market and the press showed resistance to its critical analysis. Under these circumstances, Goldenstein transformed the panorama. In his classes he advocated a disruptive conception of photography, detached from the representation of traditional genres such as landscape or portrait, black-and-white, medium format or the primacy of technical mastery; at the FGCCRR he gave visibility to all that was resisted. Also in complicity with Gumier Maier, curator of the Gallery of the Ricardo Rojas Cultural Center (GCCRR), he brought forward the communion between visual artists and photographers who, like water and oil, did not mix until then. In his workshop and in the Fotogalería everything would come together: visual arts and photography; photographers and artists; novices and professionals; artists and documentary filmmakers; black-and-white and color.3

Goldestein claims to have been unprejudiced. He exhibited fashion photographers, documentary photographers, including photoclubbers. Photographers of his generation such as Res, Marcos López and Julio Grinblat also exhibited. In several interviews he explained that he was interested in young people distanced from convention and photographers with experimental projects far from their main works. He was not guided by taste or ideology. "I want to show people of my generation and also include things that I had generated in others. Unprejudiced works. And I had to show them, because there is no point in having an unprejudiced artist if there is no one else to show it. And that did not exist in photography. I can brag about being the most unprejudiced of all those responsible of photogalleries."4 The space was not dedicated exclusively to exhibiting the work of his students, but the interrelation between the spaces was undoubtedly symbiotic.

Photography at the edge of other artistic languages; the FGCCRR at the edge of the emblematic Rojas gallery—from the edge of the edge, Goldenstein, through teaching and curatorship, inaugurated an aesthetic vector that would give rise to another way of understanding photography and art. Unlike what happened with the aesthetic paradigm called "art of the Rojas"—conceived by Gumier Maier, with which the artistic production of the nineties was identified and that came to an end at the beginning of the new millennium, around 2001 with the introduction of ways of doing and circulation linked to the concept of ‘post-crisis’5—we could affirm that Goldenstein's proposal is still in force today. But Goldenstein not only proposed a new way of understanding photography, but also postulated a new spatial grammar in relation to the photographic: he established a system where a coherence ruled between the architectural space he was in charge of (limited in size), the montage design (synthetic) and the photographic language (characterized by the economy of resources). As few others did, he understood that the way of exhibiting went hand in hand with the type of production exhibited.6 His classes and curatorial work brought into crisis the conventions of making and exhibiting in terms of spatial arrangement, choice of media, sizes and formats little explored.

Through his teaching and curatorship, Goldenstein not only inaugurated a perspective that revolutionized the canon, but also broke the sectorial logic of art in Argentina. Always encouraged to push the limits one centimeter further, his classes and curatorships were a true laboratory, a hybridization that modified the territory without a doubt.

Overflow and Containment

Just as Goldenstein was characterized by the lack of prejudice, for visual artist, writer and curator Fernanda Laguna it was the needs dictated by the heat of the context, desire and hyper-productivity that determined her artistic profile. Before inaugurating Belleza y Felicidad (B&F) and the pedagogical project in Villa Fiorito, Laguna was already well established in the art world. In 1994 she had her first solo exhibition at Rojas and in 1997 she had been part of Tao del Arte, an exhibition that became a myth.

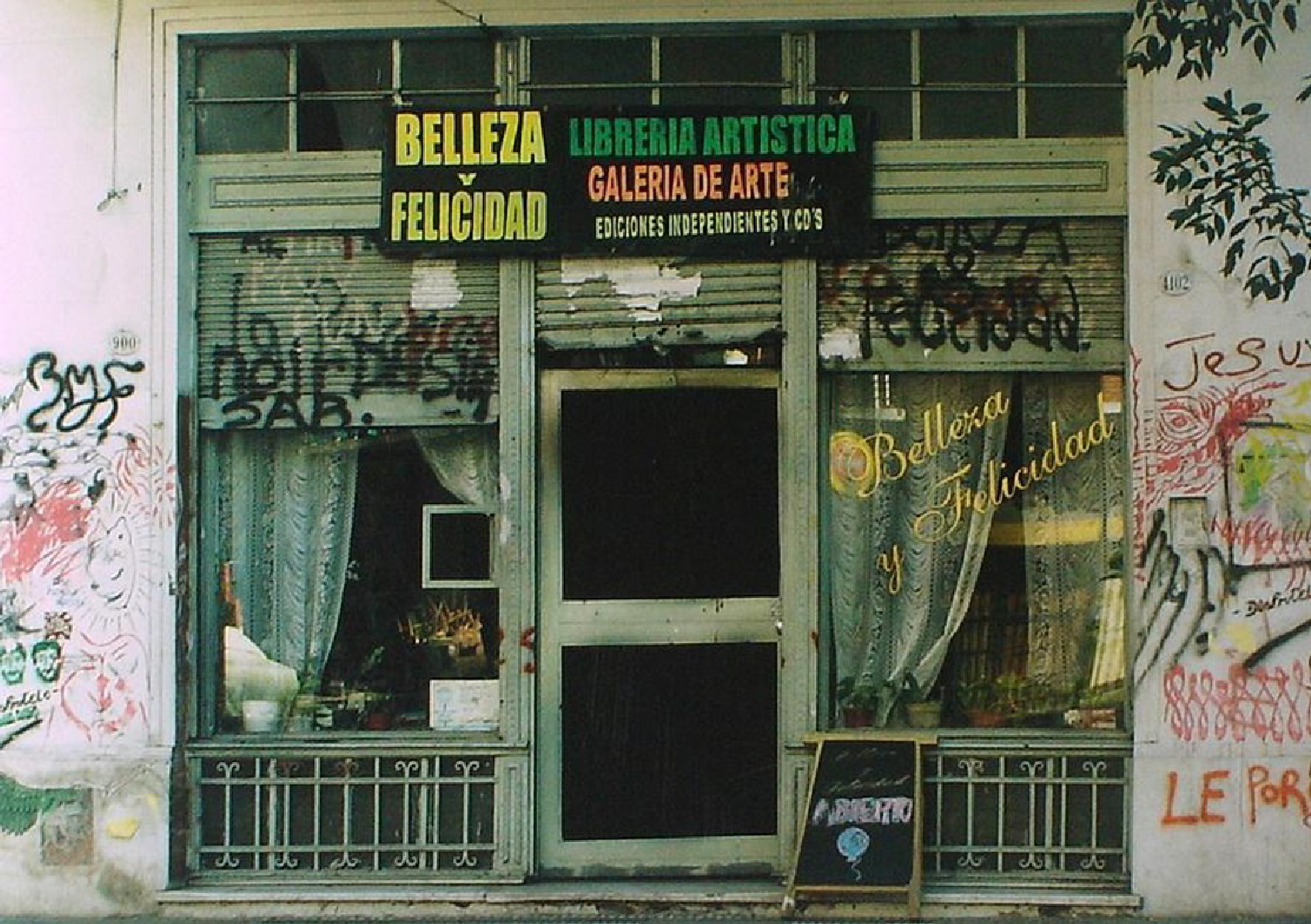

Steps into the new millennium, Laguna, together with writer Cecilia Pavon, opened the publishing house and art gallery Belleza y Felicidad in a place in Almagro, a neighborhood on the periphery of the Buenos Aires art circuit. There, the program was not limited to a publishing catalog and exhibitions (more than two hundred were held) but expanded far beyond with parties, readings, meetings in an elastic whole where friendship and the absence of limits between art and literature, private and public universe, kept the place alive and captive. The gallery had a pedagogical drift in the city of Villa Fiorito, together they constituted a place of action and containment in the context of the economic and social crises that cyclically crossed Argentina since its creation.

At B&F, writers, artists, and neighbors all came together in a festive atmosphere. It could be said that just as Gumier Maier, mentor of the Rojas gallery, took up the advocacy for certain art works to be understood as artistic, B&F, in the antipodes, sought to erode the halo of sacredness of art, although not its ritual aspect. Created before the strong economic and political crisis of 2001, sustained during and after it, B&F was an important reference regarding the centrality of social ties for the construction of spaces of representation and belonging. The new modes of sociability that would take hold in the 2000s, based on affective affinities, would constitute a new way of making and understanding art. Laguna's aesthetic conception, besides being linked to the circumstances, was marked by the vertigo of production, which determined the rhythm of what was happening there. "We wrote in the morning and published in the afternoon," Laguna declared.7

Cecilia Pavón was at B&F until 2002 and Laguna continued at Almagro district until 2007. The artists who circulated there were numerous and they made the place a platform that for many of them would later be fundamental in their careers. I am thinking of Diego Bianchi, Mariela Scafti or Cecilia Szalkowicz to name but a few. B&F, just like the FGCCRR, worked from the margin that became a convening epicenter—an overflow where no outside, no marginality existed. "In 2003 I started in Villa Fiorito with an art gallery and art workshops for children after I met a woman in the street who was from the neighborhood. We became friends and we started working together. I had a gallery in the capital and several spaces in Buenos Aires were opening branches in Europe and the United States. Thus (...) I also wanted a B&F branch so as not to be less, and that's why I opened the branch in Fiorito. My slogan was B&F, a step aside, instead of a step forward. I thought it was powerful to take the center to the periphery. It was an event that was artistic and not only social."8

Laguna went against the process of expansion and insertion in the market that other spaces were going through when she decided to open the B&F branch in Villa Fiorito, a huge area in the southeast of the province of Buenos Aires where thousands of families live in a precarious economic situation. It was there that the gallery first opened in Isolina's house, the B&F school and then the Liliana Maresa High School, a project in which artists Lorena Bossi, Juan Bahamondes Dupá, Ariel Cusnir, Paula Domenech, Sebastián Friedman, Leandro Tartaglia, and Dani Zelko participated along with the school's teachers. "At the beginning we were more interested in the pragmatic, in the sense of transmitting knowledge that would be useful to the kids for employment (...) But we realized that self-knowledge at some point is more important and more pragmatic as well. To get a job, you not only need to handle a tool, you also need to talk, you need to convince yourself that you can do it (...) and an art workshop is a means that allows you to generate a flexible mind." From the beginning, Laguna's place in the field of art education was related to her ability to identify the need to generate spaces of containment and production in the right place and at the right time, creating community.

Emergency

Roberto Echen, a great promoter of contemporary art, completes the trio. Trained as an engineer and artist, Echen served as chief curator and artistic director of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Rosario (MACRO) between 2004 and 2011. Present since the founding of the museum, his teaching experience determined the profile of the exhibition program policy, defined by a marked pedagogical character.11 It is also worth noting his place as a forerunner of a genealogy of institutional curators who understood that the narratives of the collection could be built with resources such as humor or irony, opening the game to creative speculation in the exhibitions of the collection as well as in the temporary ones. Furthermore, he also encouraged an unprecedented work dynamic at the institutional level, that of collective curatorship, making it not only an exercise that exceeded the limits of the curatorial department with a flexible, cooperative work modality capable of breaking with the specificity (not specific) of this practice, integrating the departments of production, administration or education in this exercise.

Just as Goldenstein was characterized by the lack of prejudice and Laguna by the circumstances, Echen chose emergence as the starting point of his work: "(...) I think emergence has to do with certain biographical times, but not only, also with times related to art consumption (...) with proposals that cannot yet be located and that may be putting something different (I'm not interested in whether new or not); approaches that have not been fixed either conceptually or practically, that do not belong or diverge from the established schools and ways of making art."12 Shortly before opening the MACRO, with years of teaching experience at the School of Fine Arts of the National University of Rosario and at the Manuel Musto Municipal School of Visual Arts, in 2002 he had inaugurated in the Castagnino Museum Zona Emergente, the cycle through which passed, among others, the now renowned Adrián Villar Rojas and Mariana Telleria, who were his students. With this initial experience he laid the foundations of the bridge between what happened in the training spaces and the institutions. In the MACRO, his gaze was focused on the emergency not as a problem to be solved, but as a focus to be given visibility.

One of the many proposals worth sharing is the one generated together with the museum team: the program Curador polimodal, which invites teenage students to work with their teachers in a curatorship of the collection. "In the first stage, students acquire knowledge of the works and their authors, as well as of certain concepts (...) through images, cataloguing cards and visits to the museum. Then comes a stage of critical reflection in which the children reflect their interests by presenting their own curatorial proposal.”13

Echen's gaze was anticipatory, his action fundamental and foundational in the art scene of the region. His work was marked by a genuine interest in generating pedagogical tools to achieve a greater expansion and understanding of art, that is to say, to transfer it to the public sphere.

From the edge of the edge, Echen, Laguna and Goldenstein form a triad where interdependent and contaminating ways of carrying out the artistic practice converge from the challenging around the challenging task of deconstructing the mechanisms of reproduction of knowledge and doings through the production of works, teaching and curatorship.