We Are Not the Only Kind of We

12/11/2021

Leia este artigo em português aqui.

The evidence presented by the scientific community regarding climate change urges us to acknowledge that new ways of relating to the world are required, in order to mitigate the destructive exploitation of our shared natural heritage. A number of disciplines beyond the field of ecology, including emerging areas of study, many of which draw on the knowledge of traditional peoples, have addressed the associated effects of modernity, colonialism and anthropocentrism. Through different approaches, the goal is to create conditions so that both human and non-human groups—through “more than human” encounters, or multi-specific relationships—are recognized in a consistent manner.1.

The challenges that this entails are enormous, to the extent that they demand from us humans, within a short space of time, a drastic reprogramming of our ways of feeling, thinking and acting, including the construction of a different kind of collective. But what role can art and education play in this process?

In this text, I try to identify how certain artists and educators have engaged with these challenges, with particular emphasis on what has been called the ontological or vegetal turn in the humanities. The examples of projects and practices that will be commented on briefly are divided into three “categories,” which seek to provisionally define different types of relationships between humans and non-humans. A focus on these relationships does not imply dismissal of the suggestions for adaptation and mitigation proposed by instruments such as the report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), particularly among those who make decisions in the fields of public policy and agro-industrial production, but it can certainly speak to us about “how that which lies ‘beyond’ the human also sustains us and makes us the beings we are and those we might become.”2.

Representing Non-Humans

The relationship between art and nature through representation has a long history, and has been configured in different ways. During the Renaissance, for example, representation based on principles deduced from observation functioned as an analysis of the natural laws—as a precursor to scientific thought—on the path to establishing a universal and objectively verifiable language, as provided by geometric perspective. With Romanticism, landscape, by seeking to bridge the gap between humans and nature, represented the natural world through images charged with emotion and feeling, so that an aestheticized version of nature became a mirror for internal subjective processes.

However, both these approaches, the perspective of the Renaissance and the landscape of Romanticism, objectified nature, meaning that—whether inadvertently or not—they constituted expressions of a colonial mindset. The notion, sustained over centuries, that nature existed at the service of the modern human, did not, however, necessarily produce an understanding of “the materiality of landscapes”, which, according to the anthropologist Anna Tsing, was only recently rediscovered. The understanding of this materiality is precisely what, according to Tsing, gives rise to the “the possibilities of coexistence [between humans and non-humans].” 3.

The way in which humans represent nature is addressed in “the nature of representation”, which according to Kohn tends to assimilate all forms of representation through the ways in which language drives processes of symbolization; that is, based upon social conventions.4.

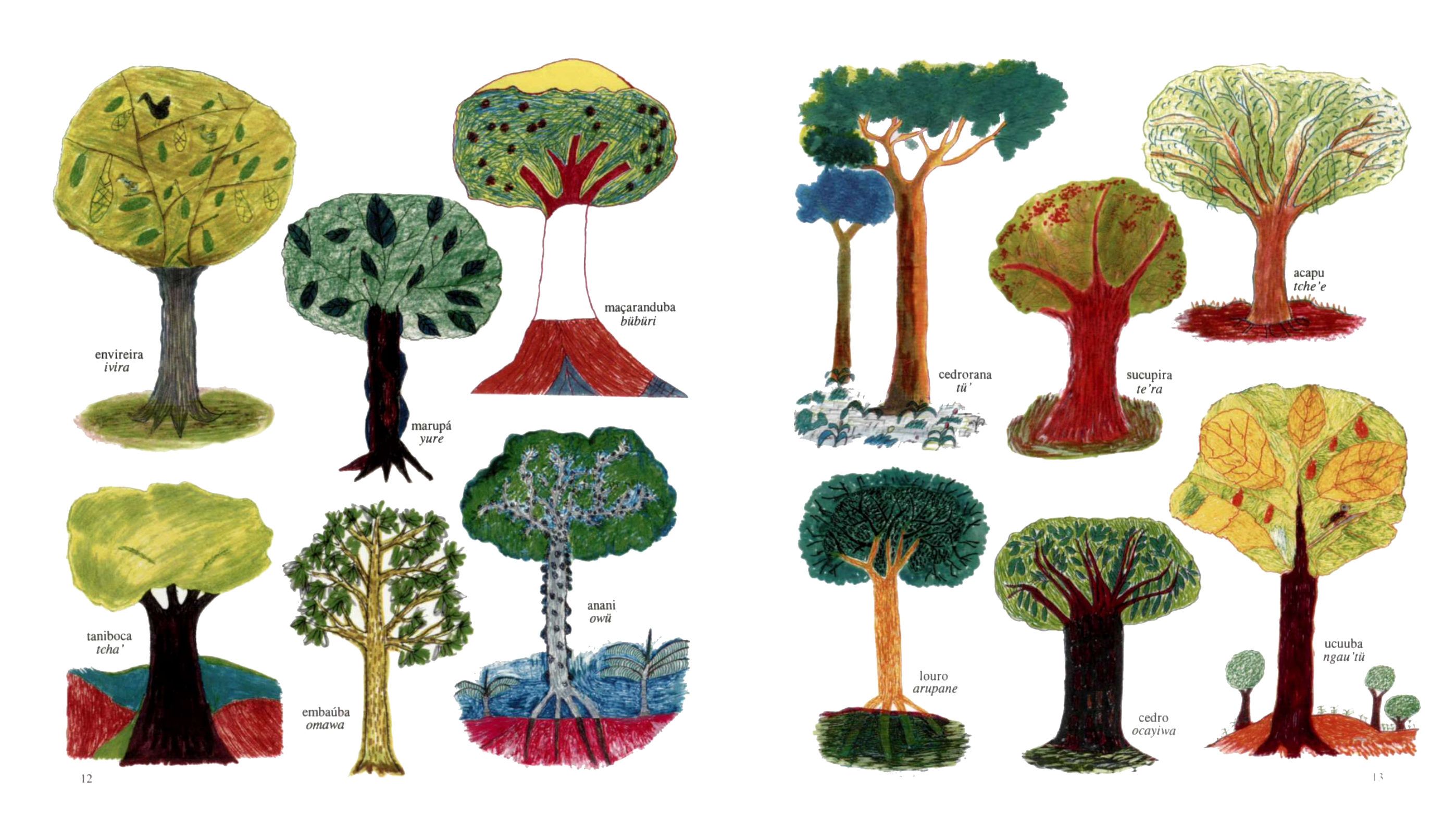

But representation, in the sense of portrayal or description, can also mediate other relationships between humans and non-humans. Originally published in 1997, O livro das árvores [‘The Book of Trees’] is the result of a project begun ten years earlier, under the auspices of the Organização Geral dos Professores Ticuna Bilíngues. The book, edited by Jussara Gomes Gruber, brings together contributions from 210 teachers from the 90 Ticuna schools in existence at the time. Intended as a teaching aid, the publication contains drawings and texts that record a "memory of the trees," in which indigenous people set out, in addition to knowledge about regional flora and fauna, different aspects of their worldviews. For the Ticuna, the Solimões River was formed from the fallen trunk of a kapok tree. From the remaining stump, an umari tree grew, from the leaves of which, when they fell to the ground, toads emerged. From the last fruits of this tree, a girl was born who married Yo'i, one of the creators; following this, people were transformed into ants and fruits into fish, which, in their turn, when they touched the ground were transformed into animals, and so on, in an endless chain of metamorphoses. At the same time, trees are described in detail, emphasizing how they are all different and how each one is important.5.

The task embarked upon by the Ticuna teachers mirrors similar work being undertaken by other individuals. Trained to be a “namer of plants,” the Nonuya expert Mogaje Guihu, also known by his westernized name Abel Rodríguez, became a repository of knowledge or "sacred visions" concerning the annual cycles, flavors, uses and ritual importance of the botanical species of the Amazon, which—as also occurs among the Ticuna—are in many cases believed responsible for the creation of the world. He says that his drawings, produced from memory or from knowledge acquired through oral tradition, rather than representing them, present trees constructed branch by branch, leaf by leaf, and so on, together with the other plants and animals with which they are inextricably related. More than "works of art," they are an attempt to preserve and transmit knowledge that is not bounded by scientific thought, but is equally essential. As Abel Rodríguez himself explains: “We don't really have that concept [of art], but the closest that comes to mind is iimitya, which in Muinane means 'powerful word'—all paths lead to the same knowledge, which is the beginning of all paths.”6.

Becoming Non-Human

Although representation can mediate other relationships, it generally implies the substantiation of a process. This characteristic becomes more evident when we compare it with certain practices that presuppose a performative dimension. In this case, a persistent empathy with non-human entities—in addition to their eventual precise representation—becomes indispensable. In addition to what can be demonstrated through certain artistic and educational practices, the interactions through which we can further pursue these types of "empathy" or "unexpected affinities" are animism, perspectivism and indigenous multinaturalism. These are forms of interaction through which many indigenous peoples envision the possibility of humans and non-humans becoming persons in each other’s eyes, or even assuming their ways of seeing.

Referring to when he studied the Achuar people in the heights of the Amazon, on the Ecuador-Peru border, the anthropologist Philippe Descola recounts that whenever he asked them why the deer, the capuchin monkey and peanut plants appeared in human form in their dreams, they told him that most plants and animals are people like us. According to Descola, the Achuar do not recognize certain distinctions between humans and non-humans, between that which belongs to nature and that which belongs to culture, according to which only humans possess feelings, thoughts and intentions. The same occurs among innumerable Amazonian peoples, regardless of whether or not they speak the same language, as well as among the Cree of northern Quebec and the Reungao, from the central Vietnam highlands, who feature among other examples cited by Descola and other authors.7 In the same way, according to Kohn, the Runa of the Ecuadorean Amazon can become jaguars, depending on how they are seen by those animals, either as prey or predator, which to them is of vital importance.8 For all these peoples, non-humans are also people, who participate in social life, or rather, in their “cultural-natural worlds.”9.

The ways in which artistic and educational practices engage with this experience are certainly diverse. However, if in this process such practices inevitably resort to some kind of representation, they do not necessarily do so in order to simulate a certain reality, but rather to live it better, or even reconfigure it. An example of this is the work of the artist, biologist and educator Emerson Munduruku, also known as Uýra Sodoma: a hybrid entity in which the artist is transmuted, calling themselves “the tree that walks.” Among the intersections that the artist addresses, by mobilizing scientific and ancestral knowledge, is the complicity between the colonial vision of trees as inert bodies and the racist and sexist violence perpetrated against dissident and peripheral human bodies. At the same time, the artist equates the reoccupation of the city by the jungle with the reoccupation of indigenous and black people of their own bodies. Since 2016, Emerson has also overseen the Incenturita Project, which involves more than 200 young students from 40 riverside communities in the interior of Amazonas state, working to compile and share stories from those territories.

Becoming with Non-Humans

So far, we have seen how other humans, particularly those from indigenous groups, whether it be within their communities or as part of the process of reclaiming their identities, regard non-humans as persons, but not yet how non-indigenous humans, informed by modern Western epistemology, relate to such worldviews. I will now address how we can engage with those worldviews, learning to acknowledge and respect them, while leaving to one side the ways in which we threaten them or are simply contemptuous of them, and, naturally, while not claiming that, in order to engage, we must all become indigenous.

In his proposal for an anthropology beyond the human, Eduardo Kohn resorts to Peircean semiotics in order to defend the fact that non-humans also represent the world, that all living creatures think, and, in addition, that thoughts themselves are alive. Considering the three modalities of representation devised by Peirce, Kohn maintains that, while representations of a symbolic nature are exclusive to humans, representations of an iconic and indexical nature—which involve signs that have a resemblance to, or, are in some way affected by, what they represent—“pervade the living world—human and nonhuman—and have underexplored properties that are quite distinct from those that make human language special.”10 In this way, rather than relying on what distinguishes us from other living beings and, consequently, separates us from the living and material world, overlaying other modalities of representation with “our assumptions about how human symbolic representation works,”11 we could engage with what we share with other living beings, through attention to the logic that structures the relationship between signs in general. In other words, “rather than make knowledge of selves impossible [due to a supposedly irreducible otherness], this [semiotic] mediation is the basis for its possibility.”12.

The problem with this complexity of relationships is identified by the educator Alejandro Cevallos, in the context of the embroidery workshops that he developed between 2016 and 2019 with indigenous women who work in the folk art trade in Quito, Ecuador. In an interview with Ángela Simbaña, a healer and vendor of medicinal herbs for 30 years in the San Roque Market, Alejandro learned that, in cases of persistent sadness, the healers would prescribe an infusion made from wild herbs and a solid stone, carved to approximate the size of a heart, which they called shunko rumi or heart of stone. Alejandro says that, upon hearing this story, his first reaction was disbelief and, immediately, tenderness in the face of such naïveté. Aware of the risk of exoticizing this story, as well as of the difference between respecting and believing, Alejandro wondered what place such a tale could have in a process of popular education which, in association with traditional knowledge, purports to be critical of modernity. He concluded that, in a world where everything is alive (plants, stones, mountains, etc.), beings seek to establish relationships of mutual care and cultivation, something that Cartesian or Enlightenment reason, based on the notion of "privilege" distinguishing us as human beings, is not able to explain, because this upbringing is based upon “a notion of health intimately woven into relationships with local ecosystems.”13.