Vibrating Bodies, Resonant Bodies: Reaching Each Other as an Expansion of Sonic Thought

11/13/2023

What these projects [of Milo Tamez and Ximena Alarcón] have in common is the expansion of sonic thought as a node between communities and the willingness to decentralize listening, breathing as a material and affective form, and the politicization of auditory experience as a mode of action in the present.

Resonance, as a possibility of reaching and engaging between bodies, offers a space for reflection on projects that emerge from contemporary artistic and theoretical programs that have been developed on the basis of a commitment to the possibility of contact. This is a kind of resistance to dominant cultural practices that are based on the verticality of the relationships between the participating agents and on the longed-for bet on the visual relationship between body and object, which often leaves out listening and its implications as part of this relationship. Sometimes the distance is considered as a factor to be discussed and rethought from the point of view of shared listening between corporealities of different geographies; at other times the spectrum of action of the musical exercise is opened up to artistic pedagogy. What these projects have in common is the expansion of sonic thought as a node between communities and the willingness to decentralize listening, breathing as a material and affective form, and the politicization of auditory experience as a mode of action in the present.

To speak of sonic environments necessarily means to speak of bodily pluralities, resonant pluralities. Firstly, because listening involves the multiple bodies that are part of a sonic exchange, as well as the material bodies through which sound passes and which in turn influence it.

Then there are the determined geographies of these environments, which play a relevant role in any sound production: visible geographies, with their own histories and direct involvement in the receptive capacity, but also invisible geographies, historical and influential in these vibratory exchanges, of life, where the processes of memory are included. If the historical, affective and material dynamics of reception and communication unfold in these games between listening materialities and resonating bodies, the political relations that shape them are always present, since we are referring to their deployment in a social, shared environment. All these games become relational and also transformational: they are outlined in a possible continuum of power and mutual influence, as the researcher and artist Salomé Voegelin1 has already suggested.

To start from a sonic environment as a territory of possibility of bodily, material, architectural, affective, binding contact, then, implies thinking of multiple crossings of resonances on all these levels, where ideally there is an openness to listening between the bodies participating in this environment; a listening that is also produced in different degrees of involvement. The ambiguity that naturally opens up in these spaces plays in favor of connectivity rather than against it: instead of conceiving a strict, binary linearity of time, and thus a restriction of the perception of the world caused by the constrictions of unification and linearity, multiple, diverse, even interdisciplinary participations are expected, dancing to different rhythms while maintaining a continuity of difference.

Among so many possible cases to revisit under these ideas, this time I focus on two of them: those of Milo Tamez and Ximena Alarcón, coming from different geographies and poetic programs, for the way they have recognized and included open, ambiguous and expansive pedagogical practices in a work that was originally intended to be performative.

Also for what this says about certain insights in Latin American artistic practices that work with sound and seek to engage more deeply with their virtual communities.

Resonance as an In-formative Process

The Mexican percussionist and composer Milo Tamez has traveled through a wide variety of musical contexts and has long played an important role in what is usually summarized as "sound experimentation." In the last decade, his work has opened up to a consideration that goes from the musical to the sonic: not music for music's sake, but music as an environment for the exchange of living experiences2 and between bodies. Beginning with compositions for drums and other types of percussion, and often collaborating with artists from both sonic and other disciplines (from visual arts to neuroscience), Tamez's work requires more and more time for preparation and reflection, as his production involves the study of shared experiences in various collective studio sessions, the review of recordings and other materials documenting those sessions, and the restructuring of compositional processes in relation to the territory in which a shared listening arrangement, experience, and verbal, gestural, and percussive exchanges are arranged.

The same transformation has taken place in his pedagogical work: in the last 30 years that this composer has devoted to teaching, his ideas of what it means for him to work pedagogically with other people have been transformed by the experience of collective listening, and in recent years the idea of music for music's sake has emerged again in the understanding of his sessions as spaces of resonance. In his pedagogical approaches, in which sound is always considered in relation to others and to the historical present of sound, Tamez seeks to create spaces of contact that often begin before the percussion itself. The compositions and their presentation in different places have promoted this change of thinking, but above all it has been caused by the relationship with formative spaces that have grown far from canonical musical structures, especially in territories far from the Mexican capital. In these formative spaces, it is assumed that all listening forms and informs both the listener and the receiver, and that in the resonant spaces a way of knowing the other is incubated. Again, a sonic thought sustained in the idea of mutual influence. Terms such as "play," "embrace," "sharing," and "intimation" begin to become key in this exchange of sensitive experiences. Also the sonorous feeling, which for Tamez, especially from the percussion, is both an ancestral link and the conformation of a being present: prior to language, the percussive exercise as a call, alert, search or summons seems primary and also awakens a sonorous will, a will to be present.

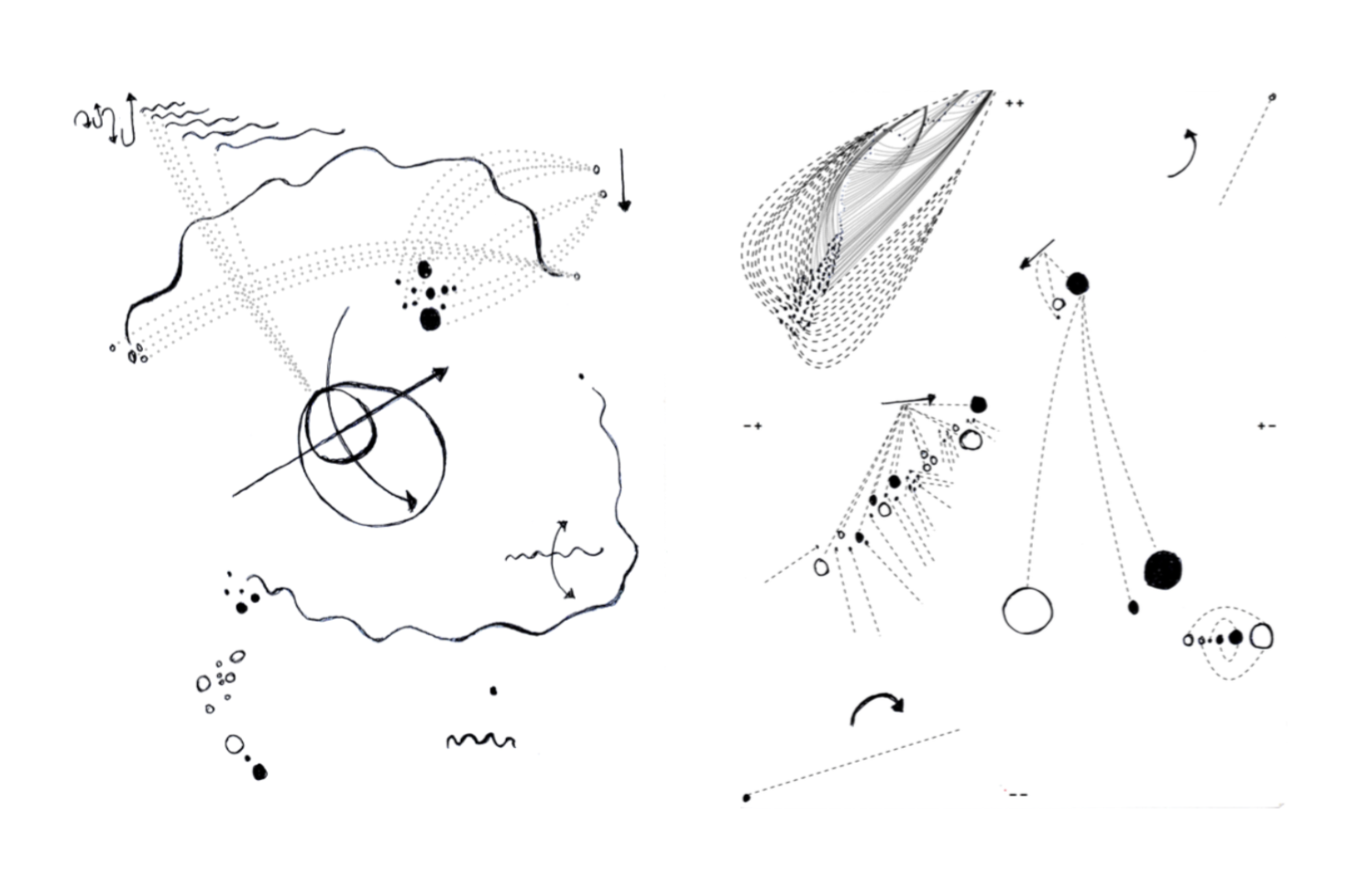

In the states that are sought in resonance, spaces of mutual influence, particular rhythms, organizational structures, and modes of thought are what are brought into play and dialogue. If this can be made to sound in a space of shared vulnerability, the following game is the search for the dismantling of multiple European constructs that have marked contemporary sound production in Latin American territories, even from areas considered musically radical. From the search among rhythms, in spaces where vulnerability is part of the sonic endeavor, what Tamez considers micro-rhythms gradually emerge: those sonic universes that the imaginative constriction of canonized structures often prevents from being shown or made to appear. From the desire for sound to the possibility of disciplinary exchange through parameterizations (disciplinary translations that tend to develop in listening and verbal dialogue), the study sessions convened by Tamez also produce documentations that nourish that other scenic universe, the moment in which the sound experience is shared again from a space of interpretation. In this way, resonance as a mutual influence occurs not only between the collectives that play percussive games, but also between formats or ways of doing, from practice to composition, from the stage to the documentary review.

Resonances from Distant Geographies, Breathing Pulse

Originally from Colombia, artist and researcher Ximena Alarcón has been developing listening methodologies from the experience of migration for a little over two decades. Seeking to understand the implications of her own process as a migrant, having lived outside her country for more than 23 years, with an extended period in the United Kingdom, she found the approaches of "deep listening" to be the triggering axis of her work. This concept is a legacy of the USAmerican composer Pauline Oliveros, who proposed an expansion of the perceptions or readings of our present by provoking full attention to the sounds of the environment, encouraging the capacity for both global and focused listening; the awareness of the present from such attention and a total physical involvement in the auditory sensitive processes that go beyond the ear, passing through all the organs of the body and also through the emotional and even dreamlike relations. For Oliveros, this way of attending to the world also worked to develop compositional strategies, and because of the nature of the proposal, multiple strategies of collective creation and practice were also developed from it. With a sustained interest in this approach, Ximena Alarcón's work takes up this deep listening and expands, from research and dissemination, the crossing possibilities that such listening promotes, to propose, in the last decade, a work that has been referred to as relational listening, and that brings into play the sense of presence in multiple factors of distance.

In the field of relations between geographical migration and relational listening, especially since her project Sonic Migrations, the mediations involved are multiplying and this artist and researcher places them at the center of her work.3 Alarcón works with very different contexts, according to the territory from which she teaches and shares workshops, listening sessions, dialogical sessions and telematic sessions: her own work is built on the contrasts of these contexts, on the stories that are told, on the specific cases of migrants who participate in these activities. If deep listening emphasizes the ability to move back and forth between attention to the sonic environment in order to horizontalize and deepen what we can perceive aurally and corporeally, as well as to focus listening on a sound point or a sound memory, relational listening also contemplates these comings and goings, attending to the possibilities of encounter in what is perceived as coincidence or proximity of migrant experiences, as well as the particularities that individual memory allows to find and show vocally and corporeally. In these remote sessions, mediation is also linguistic and technological, two universes in which experience and materiality are once again linked.

In the case of the telematic sessions, Alarcón has explored these mediations more and more deeply, finding herself in the sensory and affective capacities of thinking and speaking in one language or another: dreaming together in Spanish or publishing theoretically in English, for example, or sharing, with sound and listening at the center, with migrant people who also often translate themselves to inhabit the present. At the same time, technological mediation, besides being a condition for connecting voices and stories from different geographies in each session, has become an axis to explore in order to make explicit the role of contemporary technological materialities that mediate vision, listening, audiovisual documentation, measurement of specific temporalities, intensities, textures, tonality, silences.

The interplay between distance and presence is echoed here in the connection between memories and sonic narratives, which for Alarcón have the potential to generate new spaces of meaning of the here, the now. Recently, as part of her collaborative work, she has developed the application project INTIMAL: Interfaces for relational listening to invite people, as she describes it, "to listen to their migrations and to propose improvisation exercises with body movements, voice and word, in network and telematic improvisations [...]."4 These exercises will be based on four "spheres of migration: bodily histories, the social body, the homeland and the land of reception" and will again consider shared listening as an environment of mutual influence, where those who listen become "resonators" of the one who improvises vocally or gesturally.5

Alarcón's proposal, both in her role as an artist and as a workshop leader and researcher, is crucial in delving into contemporary searches for contact based on expanded or open notions of what the resonant means; in her case, the sonic space between deferred times and territories that establish contact from the voice and prioritize memory is problematized. In addition to the discursive dialogue (telling a dream, describing a scene, narrating an episode that has marked a person or a community), sound gestures, murmurs, echoes, breaths are also involved.

Air and vibration, before a word is spoken, as a material that is also ready to be shared, as a manifestation of present life, but also as the will to speak. Multiple recoveries of eco-geographies that resonate, in this case, through a network of sustained distance and that, like the proposal of Tamez's sessions, are based on the exposure of vulnerability and on the possibility of recognizing universes with particular rhythms, not necessarily visible, but alive and breathing.