(In)curate Visualities: Educational Practices in the Works of Andréa Hygino and Maria Auxiliadora Da Silva

06/06/2023

The term ‘(in)curate visualities’ attempts to approximate what is disclosed and what is still covered in artworks that touch on educational topics. [...] The artworks’ analysis will imply some of the reading possibilities [...] which invite viewers to the debate about education access and permanence in the Brazilian context.

What are the possibilities in a visual material for dialoguing about education and access? This article investigates the political artworks of the Brazilian visual artists Maria Auxiliadora da Silva and Andréa Hygino through a decolonial analysis to associate them with the debates on visual perspectives about educational access in Brazil. The term ‘(in)curate visualities’ attempts to approximate what is disclosed and what is still covered in artworks that touch on educational topics. Maria Auxiliadora’s artwork Mobral (1971) and Andréa Hygino's triptych work Protótipos Inadequados [Inadequate prototypes] (2021) show how two generations of artists visualize similarities and differences in access to education in Brazil, mainly among marginalized communities.1 The artworks’ analysis will imply some of the reading possibilities that are present in the multiple narratives of Maria Auxiliadora and Andréa Hygino, which invite viewers to the debate about education access and permanence in the Brazilian context.

Maria Auxiliadora’s Educational Visualities

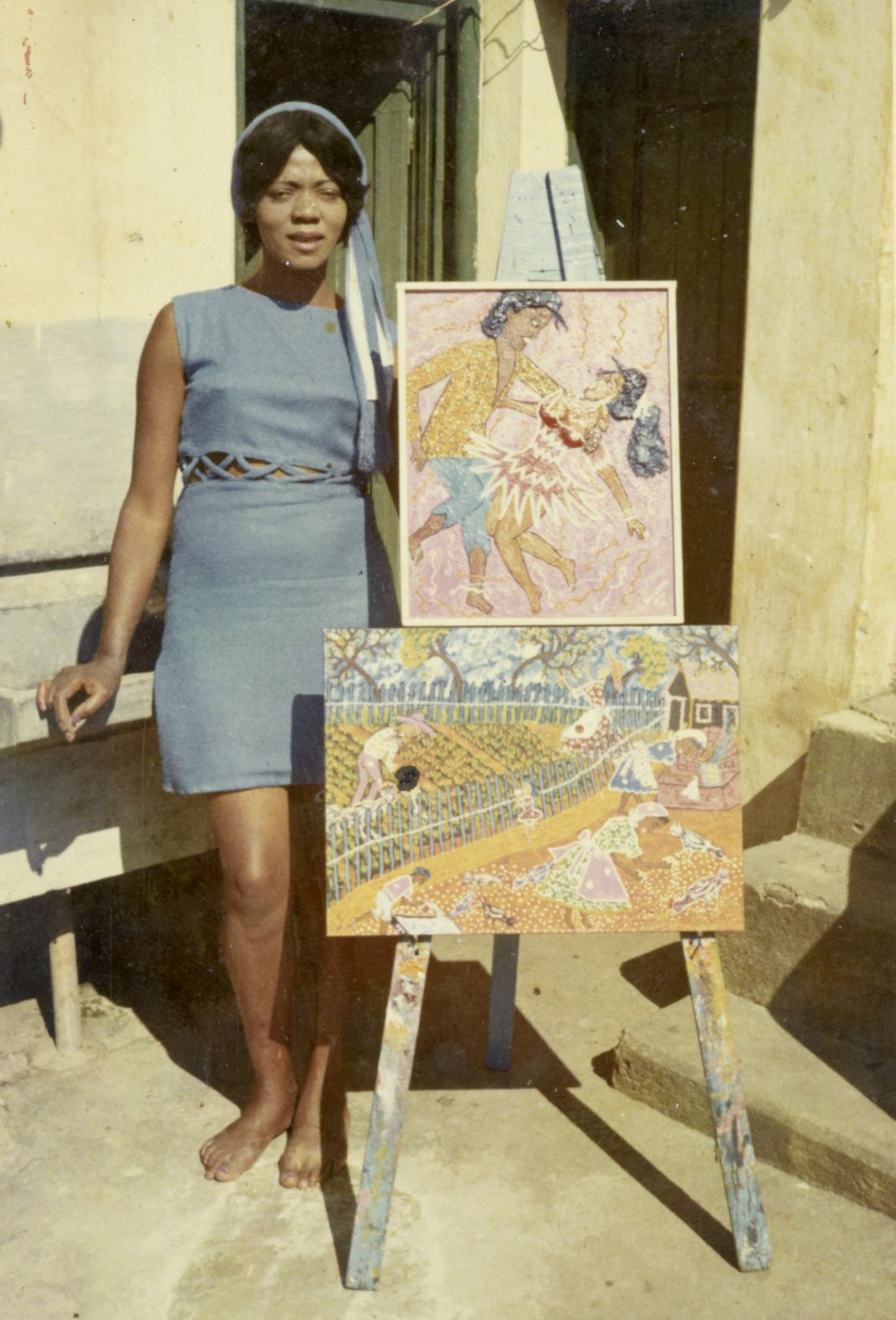

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva (1935—1974) was born and raised in the countryside of Minas Gerais state, within a family with an artistic repertoire that encouraged her to paint at the age of thirteen. The materials used by the little girl were the ones available at home, such as charcoal. Later, she acquired other painting tools and techniques, such as oil paint and embroidery. Maria Auxiliadora’s educational and artistic background references the 1950s and 1960s, a period encompassing the Brazilian dictatorship and before the 1988 Constitution. This information will be relevant to comprehend her visual representation of education inequality in the country.

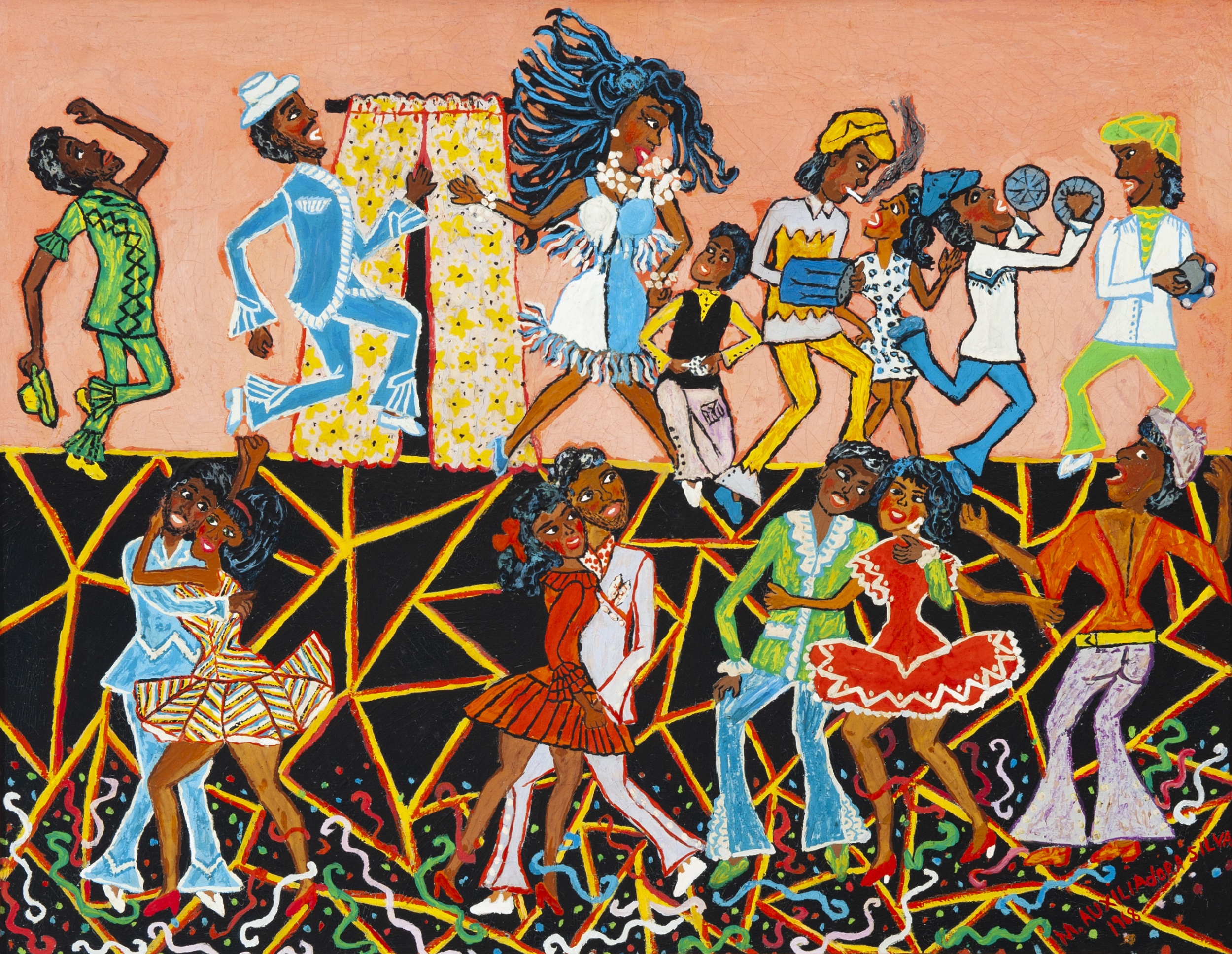

The artist is well known for her colorful aesthetics, calling the viewer’s attention to social topics that dialogue with her routine and the strategies to route possibilities for excluded communities, especially Afro-Brazilian women.

Maria Auxiliadora's work circulated outside the art market, which the Art History narrative primarily justified due to her status as an artist craftswoman and her self-taught processes.2 This colonial and binary distinction between fine arts and craft arts carries disproportional and biased values that extend to the artist's existence. Maria Auxiliadora learned from her artistic family’s knowledge and used fine arts and innovative techniques in her visual production. However, she confronted racial, gender, and class prejudices by being present in street art markets with her work, which was broadly acceptable. Also, her artistic research portrayed in Mobral (1971) confronted the rules concerning the military gaze of the period, bringing marginalized communities as protagonists in diverse backgrounds.

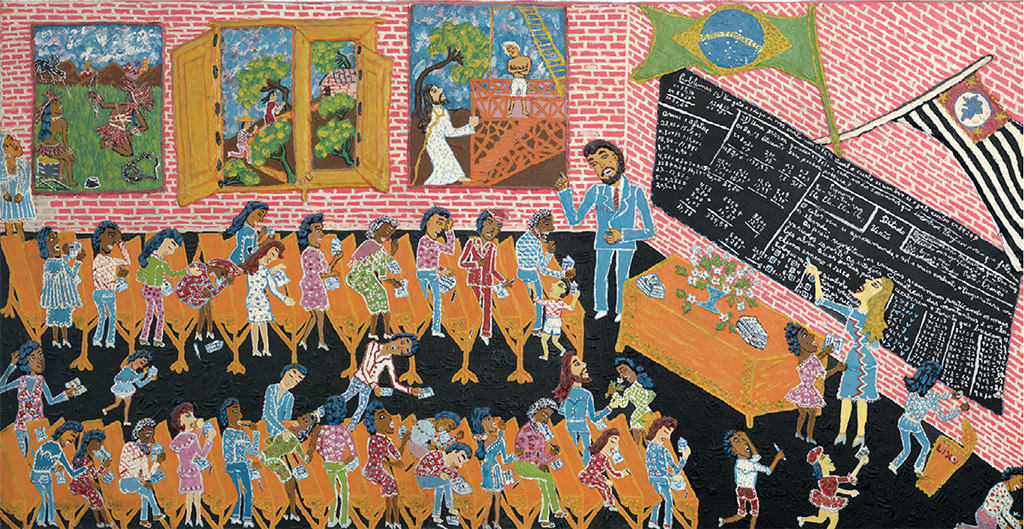

Mobral is a painting that diverges from the Brazilian modernist production at the time, adding to the oil paint plastic clay and her own hair to compound the painting's materiality, thus emphasizing the painting's bidimensionality. It is the artist's technique to approach the reality of the body and the costumes in the artwork, bringing tridimensionality to the viewer. Moreover, the artwork is a painting in dialogue with embroidery, primarily through the costumes that simulate textiles and ornaments. Da Silva builds a mixed technique performing painting and sculpture simultaneously. In Mobral, we see an educational environment represented by the artist analyzing the forms in dialogue with the artwork’s narrative. The space portrayed is the Mobral3 system, a project that was part of the National Movement for Literacy that appeared during the dictatorship and lasted between 1964-1985. The project replaced the former National Education Plan, a progressive educational model created by the social educator Paulo Freire. The Mobral teaching system worked at nights and offered free classes to illiterate or semi-literate youth and adults.4

Maria Auxiliadora suggests in this piece that black communities were the majority in these school environments to access literacy and, consequently, achieve welfare standards. It portrays a classroom as a chromatic space, with students dedicating their attention to the teacher and the writings on the blackboard in their learning process. The characters wear flowerful clothes, which also expand throughout the classroom environment and furniture. The flowers are Da Silva's skill at embroidery, which she extends to another medium: painting. This motif goes beyond a merely decorative field, being a fundamental part of the construction of the picture that is present in most of the artist's works.

Maria Auxiliadora develops a dialogue learning space in her representation of the classroom with a deconstructed dynamic room led by teachers and students, which is quite different from the military intentions. The military’s work was to surveil and control the educational process through systematic read-and-write learning without a critical world interpretation, as Paulo Freire had proposed before.

Black communities, as the prominent public of this educational program model, carried on the consequences of this academic control, which remains the exclusion logic that kept their bodies away from society integration perpetrated throughout the enslavement period and still to that moment. In a way, Maria Auxiliadora breaks the exclusion symptom, presenting a painting where educators are in dialogue with the class. The students are in different positions around the classroom, as in the chairs reading or speaking with each other, bringing the viewer a dynamic class environment.

However, the military environment is still present, with the students occupying large and rigid seats, some of them attending to the notebooks about basic school subjects, other learners are attentive to the papers and the teacher's speech in front of the class. The blackboard has basic Math exercises written on white chalk and dialogues with the Mobral system rules for teaching with no critical reflection about the world. Even so, on the wall, the artist historicizes moments of the Brazilian narratives as the presence of the Indigenous population and the labor workers on the farms after the end of enslavement. Although the binary and colonial separation of rural and urban, the representation of Indigenous communities and working laborers were topics that preserved historical contexts present in the students' everyday lives.5

Mobral ended in 1985 and was replaced by other programs that intended to be more democratic in their conceptions and practices. However, symbolic actions of control and surveillance have maintained the colonial structure in the Brazilian educational system. More recently, the artistic work of Andréa Hygino engages in this perspective questioning the educational system's limitations through school items of furniture.

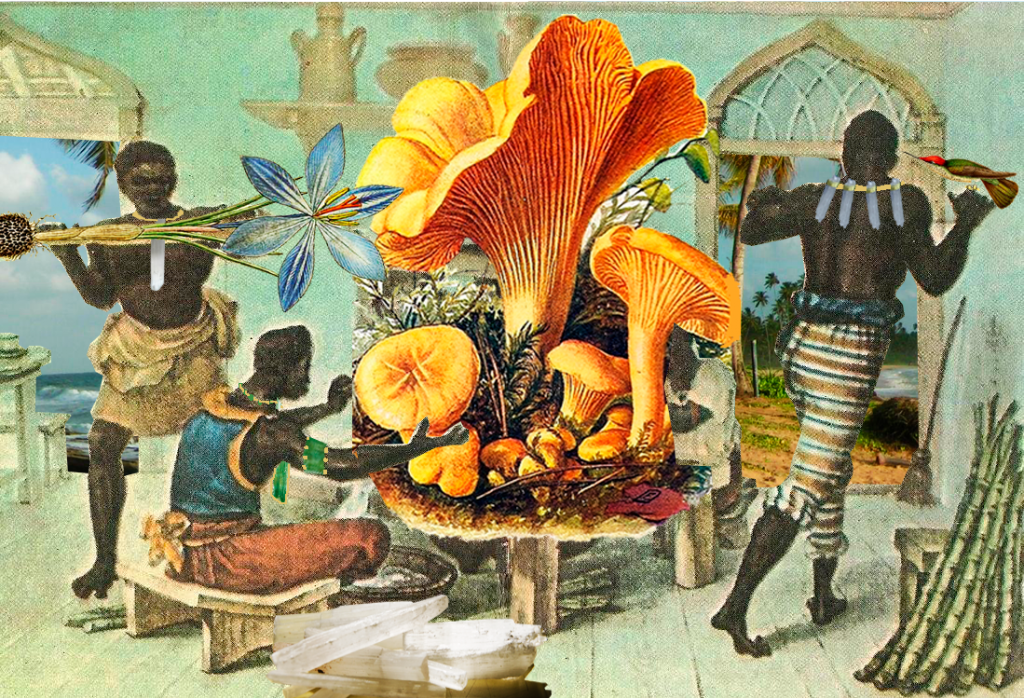

Andréa Hygino´s Educational Visualities

Andréa Hygino (1992) is a visual artist and art educator from Rio de Janeiro, whose work intends to criticize educational perspectives in Brazil. Her production came after the 1988 Constitution, in which education became a universal right in the country, a guarantee that the State has accountability to respect and promote throughout all the population. Hygino produces artworks about education to express her ambiguous feelings of exhaustion from being an educator and self-supporting her artistic work and inspirations to make art. Protótipos Inadequados [Inadequate Prototypes] (2021) is a series of artworks that visually confronts the authority imposed upon school learning through the use of the chair.

This triptych sculptural work consists of a series of school chairs built with different writing supports, displayed on a grayish background, facing forward or sideways. Hygino appropriates the memory of the school chair as an uncomfortable place to sit/learn, based on her experiences and those of colleagues, to criticize seat rigidity. The first perspective contemplates materiality: how the wood used for school furniture could discomfort the students’ bodies to accommodate themselves; it is not a welcoming object for a study environment. The other assumption is that the chair metaphorically symbolizes a normativity imposition as an object. Normativity refers to Western knowledge imposed on diverse world cultures, such as Brazilian Indigenous peoples and Afro-diasporic communities. Both interpretations have designed distinguished assumptions with each of the works in the series.

The first chair sculpture is called Educação Superior [Higher Education]. With a light wood material and a fixed seat position on a gray background, the artist builds the school desk at a higher height than the chair's seat. The image intrigues me because the learning process is represented by a seat and table support. Hygino’s work approximates Maria Auxiliadora’s visual research as both claim bodies that do not fit in this seat, adding the hierarchical position represented by the chair. Regardless of the chair ingress, the access table for reading and writing is distant from the student.

The artist emphasizes how this artwork demonstrates her experience in educational institutions, where she faced metaphorically elevated school desks to survive in those places.

Historically, Brazilian education became effectively open to all society through policies initiated only in the 1988 Constitution, guaranteeing by law access to education. After the 1988 Constitution, most structural access exclusions were barred by law. Afterwards, public policies to guarantee educational access to a diverse and critical curriculum6 about the Brazilian population were also created. However, the country's inequality remains a barrier for guaranteeing access to education to part of the vulnerable population.

Many of the marginalized communities that occupy these educational seats have experienced a high social inequality in the country which evidences the difficulty to access and permanence in schools, or to learn about the diverse narratives of the country. The process to have quality in Brazilian education is proportional to financial conditions, which exposes the class and racial inequality in the country. The elevated school desk symbolizes these inequalities and reinforces the barriers that the majority of the Brazilian population struggle with to achieve the basic: the right to education.7

The middle frame, Ambidestra [Ambidextrous], directs us toward this strategic discussion, representing the chair with two sides of the school desk. Ambidextrous means accessing two possibilities to sit and interact with the table support.8 Hygino's works offer another knowledge to comprehend the chair, she also proposes to bring more references to the chair's usage, respecting the diversity of bodies and histories. Transposing this reading to the educational debate, Hygino highlights how racial, social, gender, and sexual barriers in society should be faced in its structure to criticize the current educational model and to review and broaden alternatives to educate the excluded sectors.

The joint triptych is a visual narrative to shift our perceptions about the form and quality of society accessing the right to study. The excluded population has the right to choose and access without constraints and to continue their learning without being excluded because of social inequality.

The third piece, Saída de Emergência [Emergency Exit] presents a brown chair back with a small ladder that suggests an alternative for escaping the structural violence. The stairs are both a symbolic and concrete representation of the interpretive strategy in which Hygino attempts to visualize an openness to her artistic field in education.

Although the chair produces discomfort due to its rigid structure that metaphorically exposes the fixed privileges of a small portion of Brazilians, the artist interferes with this rigidity by opening the structure and other critical and inventive readings to access and occupy this piece of furniture/education. Maria Auxiliadora also unfolds this inventiveness, bringing a different universe of learning that also intervenes in the rigidity of the classroom and the military system. Maria and Andréa have produced art in different periods but with historical similarities touching on educational control/surveillance, which bring about similar dialogues on the constant educational deconstruction, exposing the urgency for accessible education.

Both artists have been active in contexts that depreciate black women's art production, segregating it to specific or stereotyped fields and undervaluing the work's knowledge and quality. Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, Andréa Hygino, and many other artists have been excluded from the colonial art canon and still build alternatives with their funds to maintain their artistic production. Artists have historically tensioned the Art system and creative productions to intersect plural visual discourses, value the artists' work, and be a tool in dialogue with society's urgencies, such as the educational access debate.

Far from any pretension to solve these problems, the artworks of Maria Auxiliadora da Silva and Andréa Hygino illustrate the visible Brazilian educational wound to discuss and claim for structural changes that remain in the country. They also demonstrate how artistic productions use a diversity of materialities, discourses, and interpretations to offer alternatives for seeking "emergency exits" in our worldly existence.9