Whirlwind of Our Words: Practices in Zapatista Autonomous Education

03/14/2023

The Zapatista arts are fulfilling the double function of, on the one hand, narrating their own history for the exercise of collective memory and, on the other, making pedagogy about the current daily praxis of autonomy.

This text is first and foremost a brief account of a period of face-to-face learning and direct observation carried out in Zapatista territory over several years. The voices that emerge here are those of the comrades themselves.

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), that force of little ants that is distributed throughout practically half of the territory of the state of Chiapas, in southern Mexico, is composed of six ethnic groups (Tsotsiles, Tzeltales, Tojolabales, Chol, Mam and Zoque). Between the cold landscapes of the high mountains and the hot tropical zones of the lowlands, the Movement has been developing a 'confederation of autonomies,’1 under a progressive strategy which ranges from the armed insurrection (1994), to the San Andres Agreements (1997)—where the word of the Mexican Government is still trusted— to the formation of the Caracoles, administrative centers where the present autonomous process of the EZLN is based (from 2003 onwards).

During my seven-year stay in Chiapas (2013-2020) I was able to approach the Zapatista Movement in several ways. The first was through the Escuelita La Libertad según los Zapatistas [Liberty According to the Zapatistas School]. This initiative of the EZLN emerged after a few years of media silence between 2008 and 2012, where the Movement stayed away from the media, without making public appearances, consolidating in their territories their own processes of organization, administration and the areas that make up Zapatista autonomy: health, justice, education, communications, agroecology, etc., without the collaboration or intermediation of NGOs or other international solidarity networks.2

This is how, well into 2013, the EZLN surprises us by inviting thousands of comrades from all over the world to the Escuelita La Libertad según los Zapatistas. This would be a massive pedagogical experience, executed in a practical, physical, corporal, concrete way, and of course, based on 'sentipensar'3 [feeling-thinking].

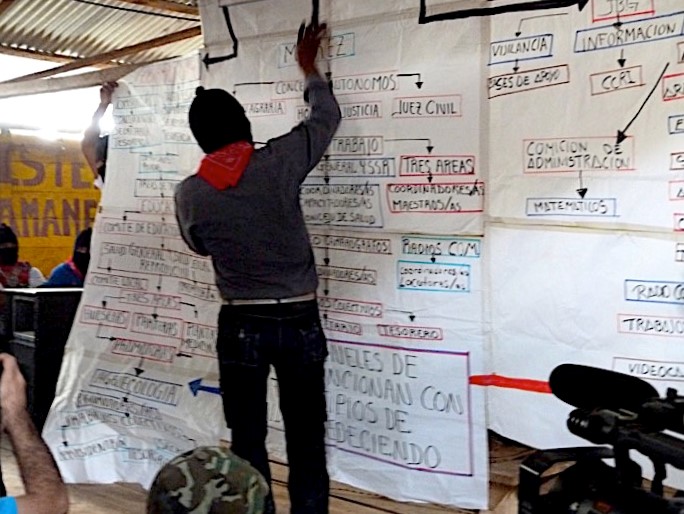

La Escuelita was an initiative of the Zapatistas to plant seeds4 of their own experience creating autonomy. To do this, they first compiled collective testimonies from the Zapatista support bases in each Caracol; these compilations formed the four textbooks for the first grade of the course that were given to each student. Then, they mobilized to pick up the students who had arrived in San Cristóbal de las Casas. We would then be divided into groups of several hundreds and directed to various Caracoles, where we would receive a class with a full auditorium on how Zapatista autonomy is built, administered and organized. Afterwards, we would again be divided into groups of five to eight people and transferred to communities deep in the jungle or mountains. For several days we were housed and assigned time to study, work in the fields, share talks, cook tortillas and drink posol. We experientially combined theory and practice through an educational device of unprecedentedly generous strategic dimensions.

«What we are doing with the escuelita is very big for us, it is an accomplishment for us because we already met other types of brothers from different countries of the world and they also met us as comrades from our towns and municipalities. They have already understood how we govern ourselves, which is the way to achieve unity among comrades as well as how to work collectively.»

The Zapatista Autonomous Government has functions, duties, rights and obligations at its three levels: local, municipal, and Good Government Council (Junta de Buen Gobierno - JBG). One of these is, of course, elementary and high school education.

Before the armed uprising, the Indigenous peoples of Chiapas were in total oblivion: the Mexican State was not providing the minimum conditions of health, education or justice. It did not even take a census to know how many children were born and died of curable diseases. Thus, when the people raised up in arms on that magical dawn of January 1, 1994, and presented their 13 demands, among those was, of course, education.

Today elementary education is carried out within the Movement with a escuelita designated for boys and girls in each community, no matter how small or remote it may be. In these schools, Zapatista education promoters teach the following subjects: Mathematics, Life and environment, Language, and History. With the exception of the first, which is universal and objective, the others were modified or created to differ from the content defined by the Mexican government's Secretary of Public Education, whose schools force Indigenous people to receive classes exclusively in Spanish,6 deepening acculturation and hegemonic definitions of race/class. In Zapatista schools, children learn to be bilingual and proud of their Indigenous mother tongue. They understand history from the perspective of the people and learn about collective work in the fields, the economic and social pillar of autonomy.

«The idea was born among several colleagues and later on the discussion was broadened and it became clear among all of us the need to start a school. It is true that we first thought of a high school. What madness, if the people have no education, cannot read or write, what nonsense to start or talk about a high school. However, that is how it was done, a high school was thought of, still taking the idea of the official schools, not being able to find the best way to say it and that is why it was called high school. It was kind of funny when it started like that but later... we thought about what education we were going to start. Literacy? School more or less formal? Elementary school or what?»

High school education is carried out at sites located in each Caracol. There, teenage Zapatistas also practice sports and dance as they delve deeper into their subjects. However, Subcomandantes Insurgentes Moisés and Galeano themselves have stated that the youth, born in rebel territory years after the uprising (therefore totally free and empowered), are now demanding access to more academic training. The Zapatista university is still a long-term dream, but the demand of the rebel youth is in some ways satisfied through the Art, Film, Dance, Science Festivals and Seminars such as El Pensamiento Crítico Frente a la Hidra Capitalista [Critical Thinking in the Face of the Capitalist Hydra], which the Zapatistas have organized since 2016, allowing artists, intellectuals and scientists from all over the world to share their knowledge with the EZLN's support bases, coexisting with the artistic creations and interventions of the Zapatistas themselves.

I am going to stop now at the third nucleus of rebellious pedagogy that I am interested in exploring: the Comparte por la Humanidad Festival.

With two versions, one in 2016 and another in 2017, Comparte has meant a deployment of political pedagogy that seeks to show a before, during, and after of Zapatismo to the world. We can understand it as an extension of La Escuelita with the same objectives but through a window to the artistic disciplines developed within the Zapatista support base communities.

This discursive pedagogy is embedded in works that also entail a chronological/contextual narrative. This timeline and narrative of the arts develops collective, autonomous themes that refer to their own history of liberation.

A first axis deals with the past, represented mainly by theater and dance. In this thematic/temporal space, the Indigenous cosmologies of the Mayan grandparents and ancestors are mainly reflected in ritual dances for agriculture, rain and the fecundity of the earth, accompanied by repetitive music and natural elements such as leaves, corn and fire. Also in this circumscription we locate the plays where the colonial, latifundista and partisan exploitation is recounted. With the participation of entire communities, these long plays—an average of 2 to 3 hours, with dialogues and scenes in real-time, that is, analogous to the time of the event represented—detail the abuses and atrocities suffered by the people of Chiapas before the Zapatista uprising.

The second thematic/temporal space is the line that deals with the present. These are the creations designed to tell us how autonomy is practiced, how the JBGs decide and operate, the work collectives, how daily resistance is lived, how the health and education promoters are trained, etc. These themes are also represented through theater plays, where each step of the autonomist processes is expressly demonstrated and exemplified from the sale of cattle to the installation of the product stores, as well as satirizing partisans, paramilitaries and paid media.

This group also includes paintings, a discipline that reflects the procedures of the autonomous project: scenes of collective work merge with images of resistance to the military presence, in crowded compositions arranged in an open plan, full of color and visual information. These collective paintings were presented hand-held microphone with a detailed description of each scene and each element. Of particular note is the frequent representation of the 'Capitalist Hydra', a concept that has become part of the Zapatista vocabulary in recent years and which exemplifies the thousand-headed monster of savage capitalism.

In the order of the future, the praises heard in poetry declamations about Zapatista autonomy inspire the world. These oral presentations cast in poetry the paths of global autonomy based on the effort of the collective being, the strength of women, and the respect for Mother Earth.

Zapatista art (decolonized, non-elitist, non-professional, non-commercialized, collective, anonymous, emancipatory, aesthetically resistant and discursively integrated) is the product of a mobilization of organized peasant masses that confirms the profoundly political and poetic structure that constitutes Zapatismo.

Therefore, the Zapatista arts are fulfilling the double function of, on the one hand, narrating their own history for the exercise of collective memory and, on the other, making pedagogy about the current daily praxis of autonomy. Both elements subscribe to the cultural tradition of the Indigenous Mayan-descendants and respond to the need for the peoples' long-term resistance in the contemporary socio-political context of extermination and exploitation of human and non-human beings.