In the Footsteps of Toledo in the Schools of A’cani

07/25/2022

The Schools of A’cani enable us to reimagine the naturalized limits between art, activism, education and what we understand by democratization, cultural rights, social relevance, emancipation, self-determination, solidarity, collaboration, public policy and collective construction.

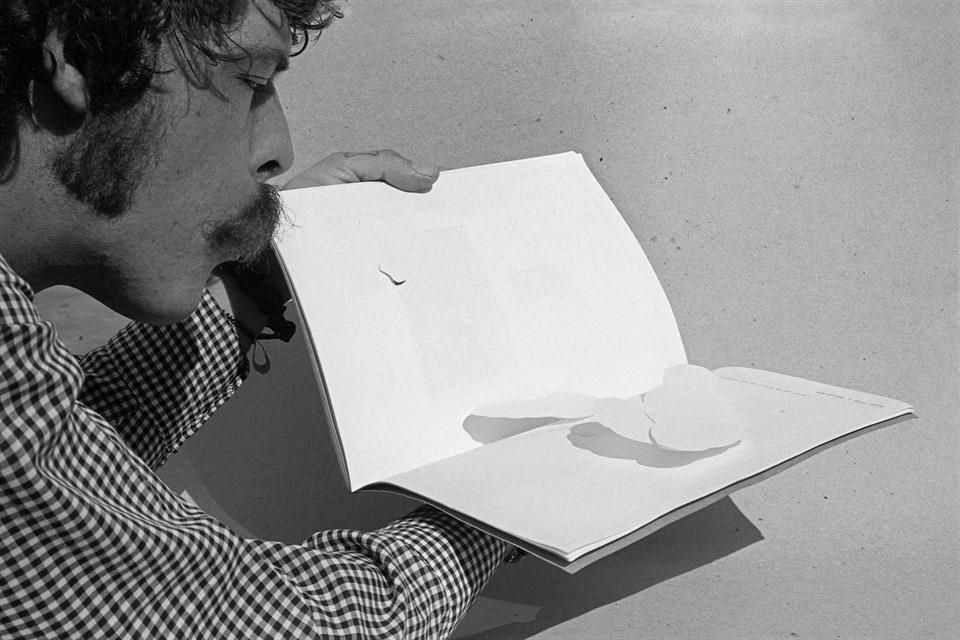

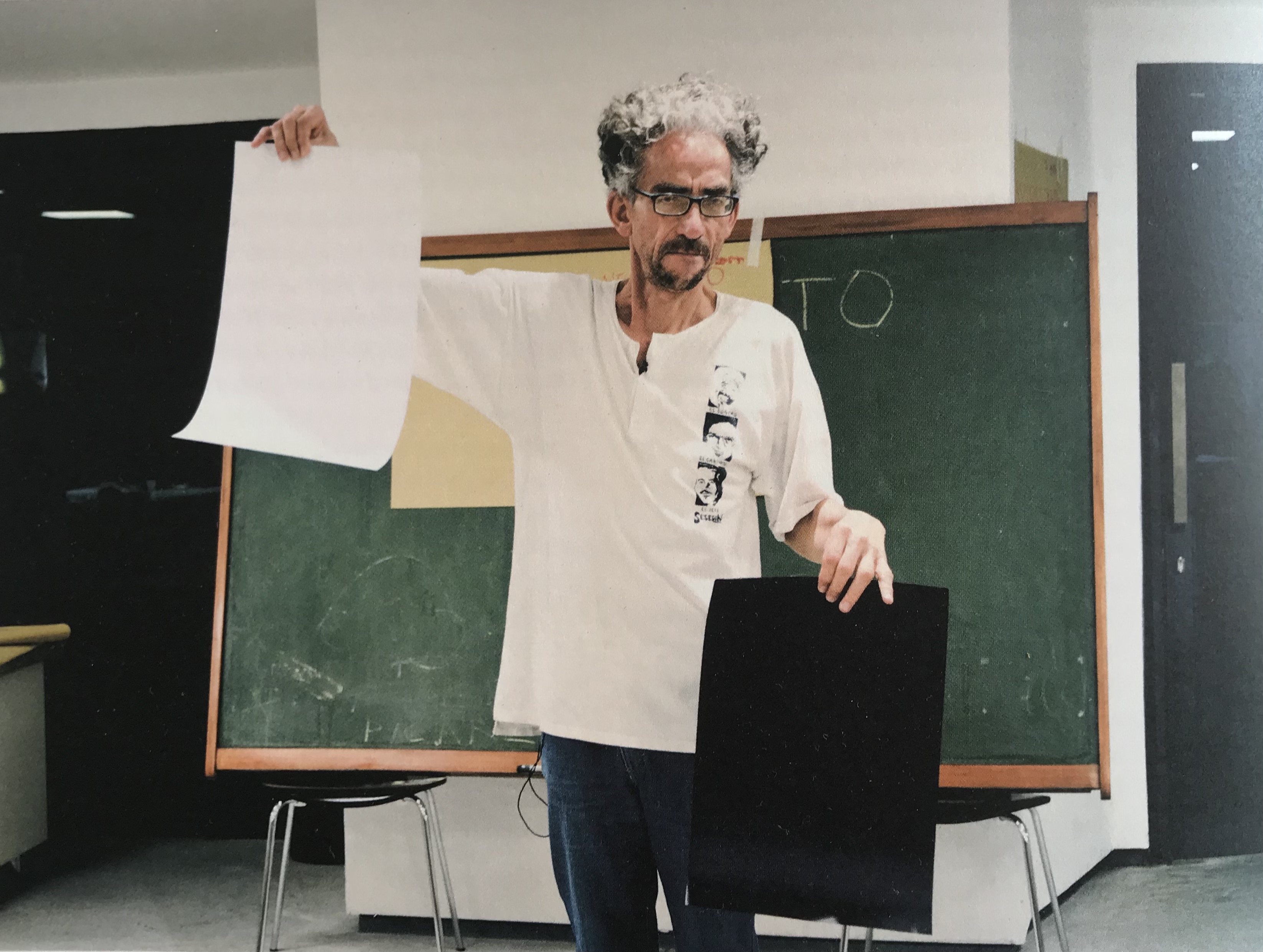

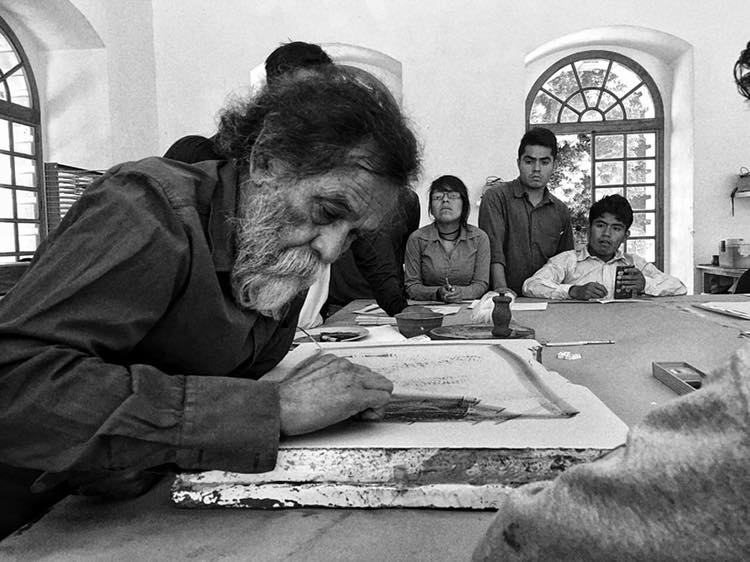

The artist and activist Francisco Toledo (Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1940), who fought his entire life against neoliberalism, dispossession, extractivism and the scourge of ecocide, bequeathed to the world of culture, in addition to a vast artistic output through which he confronted hegemonic constructs, a series of teachings, the influence of which can be seen in the educational institutions he founded. A’cani can be translated from the Zapotec language as “a call to action.” With this notion as its background music, the following article will offer a reflection not so much on the methodologies and learning resources generated by Francisco Toledo,1 but rather upon the educational dimension of the alternative initiatives that he created, and which we will call here the Schools of A’cani, schools that have inspired certain fundamental questions, such as: “why educate?” “Who teaches and who learns?” And, “in what contexts?”

As we will see, the teachings of the Schools of A’cani have to do not only with initiating artistic learning processes, but with the disruption/creation of the conditions required to make such processes possible: in other words, with the providing of a cultural space for the defense of the political imagination and contingent reality, while understanding that it is a construct that can be altered.

The Schools of A’cani enable us to reimagine the naturalized limits between art, activism, education and what we understand by democratization, cultural rights, social relevance, emancipation, self-determination, solidarity, collaboration, public policy and collective construction.

In the earliest days, at least, the Juchitán House of Culture, the Oaxaca Museum of Contemporary Art (MACO), the Jorge Luis Borges Library for the Blind, the Oaxaca Institute of Graphic Arts (IAGO), the Oaxaca Paper Art Workshop of the San Agustín Center for the Arts (CaSa), the Ethnobotanical Garden, as well as the Francisco de Burgoa Library, engaged in a strategy based upon a diagnosis of certain “infrastructural gaps” that needed addressing in the Oaxacan context, but which were unrelated to the monumental or utilitarian aspects associated with tourism or real estate. On the contrary, in a context of immense shortcomings and educational issues, these Schools of A’cani mobilized infrastructures focused on other political questions, associated with the de-bureaucratization of cultural policy and education, citizen participation through cultural practices, the search for alternative models of agency and governance networks, and the defense of human rights, territory, heritage and indigenous languages (Oaxaca being the Mexican state with the highest number of spoken languages).

Each one of these Schools of A’cani, developed in collaboration with various actors, civil associations or organizations, and government agencies, had a considerable impact on diverse contexts in Juchitán, the city of Oaxaca and San Agustín Etla, by creating cultural spaces that responded to the specific needs of their contexts, where such needs had not been addressed before. The Juchitán Lidxi Guendabiaani (‘House of Culture,’ in Zapotec), established in 1972, comprising a museum, a library and a space for workshops and exhibitions, influenced the social and cultural fabric of the city in which Toledo himself was born, while also establishing itself as a fundamental aspect of the political history of Oaxaca and the country as a whole, by becoming the center of operations for the Popular Socialist Party (PPS) and the Coalition of Workers, Peasants and Students of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (COCEI). The archaeological collection of the Juchitán Lidxi Guendabiaani is composed of more than 700 objects, protected today by the National Institute of Anthropology and History, and it was formed from archaeological pieces donated by friends of Toledo and the inhabitants of Juchitán.

The Oaxaca Museum of Contemporary Art (MACO), created in 1992, the Oaxaca Paper Art Workshop, opened in 1998, and the Oaxaca Institute of Graphic Arts (IAGO), founded in 1998, which houses an important collection of objects, as well as the Library (BIAGO), specializing in art, the “El Pochote” Film Society, the Manuel Álvarez Bravo Photographic Center, the Eduardo Mata Audio Library, together with a space for exhibitions, have not only contributed to developing the city’s cultural scene, composed of an artistic community of painters, sculptors, photographers, filmmakers, musicians, promoters and managers, but have also generated a diverse cultural offering for an extremely varied public which, since their creation, flock to these spaces with their marked educational vocation, which is particularly supportive of students from all levels.

The San Agustín Center for the Arts (CaSa), located in the La Soledad Yarn and Fabric Factory in the town of San Agustín, Etla,2 founded in 1883 by José Zorrilla Trápaga and abandoned in the 1980s, was restored thanks to an initiative encouraged by Toledo, the efforts of the architect Claudina López Morales, and support from CONACULTA, through the National Center for the Arts (CENART), the State Government, the Harp Helú Foundation, and the Friends of the IAGO. Since it opened its doors in 2006 as the first ecological arts center in Latin America, it has hosted a program of international exhibitions and artistic residencies, while focusing particularly on the development of a solid program of artistic education closely aligned with urgent environmental issues (incorporating the visual arts, literature, textiles, ceramics, glass, dance, design, dramaturgy, music, cinema, architecture, curatorship and cultural management). Similarly, CaSa has made production spaces available to artists in training, including graphic and textile design workshops, and ecological photographic laboratories for developing and printing. This School of A’cani has left a profound legacy of learning experiences upon several generations of artists, managers and curators, who have been trained there or who have collaborated with it in some way.

The Jorge Luis Borges Library for the Blind has, since 1996, provided a cultural offering for a sector of the public often forgotten by cultural institutions. The library is home to a collection of books in braille and hosts a series of permanent braille and Mexican sign language workshops, as well as offering scholarships and support for blind and visually impaired students. At the same time, the work of inventorying, classifying and conserving the collection of the Francisco de Burgoa Library, which houses a collection of approximately 30,000 titles, mostly originating from convents, has had a broad impact on cultural and university life (it belongs to the Benito Juárez Autonomous University of Oaxaca), and on the work of researchers, thanks to those activities involving the recovery of antiquarian books and documents of major historical importance, which have been of particular relevance in Mexico.

Finally, as part of the Santo Domingo Cultural Center, where the Francisco de Burgoa Library and the Néstor Sánchez Newspaper Archive are also located, the Oaxaca Ethnobotanical Garden began life as an initiative supported by Toledo and the civil association PRO-OAX (Board for the Defense and Conservation of the Cultural and Natural Heritage of Oaxaca). The Ethnobotanical Garden has a nursery, a seed bank, herbarium and library, and it offers a program of activities. It presents itself as “ethnobotanical” because it is founded upon the notion that plants have a cultural significance capable of opening up worlds that renew our way of looking at our surroundings, enabling us to develop a different type of relationship that is more respectful and caring towards the environment. Planted since 1998, the garden displays many plants that are endemic to Oaxaca, which is the Mexican region with the greatest variety of flora and fauna in the country. In addition, it engages intensively in the tasks of collecting, planting, caring for and propagating, researching, conserving, and disseminating the importance of biological diversity, as well as addressing that diversity’s neglected links with the cultural history of the state.

Close inspection reveals that, behind all the Schools of A’cani, or “cultural enterprises,”3 as they were once described by the writer, journalist and chronicler Carlos Monsivais, there exist a number of shared questions:

What must be necessarily and urgently changed? How and where can we find less elitist and centralist spaces that offer more sustainable and horizontal forms and settings for education, creation, production, food and caring for each other, and for all living beings? What strategies can be employed to enable culture to activate the political imagination as a tool that reinvents, without replicating, the modes of accessing and operating traditional education, while exploring possibilities for teaching or inspiring learning experiences both within and beyond institutions?

The Schools of A’cani light for us certain paths, enabling us to see with the blood from which our eyes are made,4 to rediscover possibilities, expose injustice and inequality, and work on — rather than ignoring — that which must be urgently addressed; to generate strategies for reinventing the role of art in community work, defined by collective responsibility and resistance exercises; to protest and confront the epistemic dominance of the north and reach out to the contextualized, situated and practical knowledge that forms part of multiple struggles and constitutes transformative practices. Or, in other words, and perhaps more simply, to recover better than we did in the recent past the desire to do in order to learn, the passion and the spirit to organize and support, through generosity, educational changes as social movements.