It is no coincidence that the three teams are conformed by couples who work together. They are people whose work and personal lives are completely intertwined; they don’t live off architecture but within architecture. Michele and Carmen involve their children in their projects; Jorge and Fabiola met talking about architecture, education, and childhood; and Daniel and Marie make research trips in a kind of motorhome they designed themselves. This form of involvement, unconfined to the professional practice or academic research, but rather also being part of the subjectivity and daily life experience of architects and/or artists—of the lived and perceived space, beyond the conceived one, in terms of Lefebvre's (2003)13 unitary theory—was a fundamental condition to be part of the project. This dynamics contributes to a much wider and complex reflection on the phenomenon that we set out to discuss. The outer walls of the school are also the outer walls of the architectural and/or artistic discipline.

DIADIA Arquitectura La Cabina de la Curiosidad Lunárquicos

EXTRAMUROS – Outside the Walls

past

Ecuador Colombia Perú

2023—II

12/12/2023 — 12/12/2023

Conclusions of the series of formative projects carried out under the curatorship of Javier Vera Cubas, based on the exchange in popular neighborhoods of Lima, Bogota and Quito.

The etymology of "school" (escuela, école, from Greek scholé) alludes to the leisure and free time reserved for citizens. Free—as Arendt (2017)1 explains—from labor and work, and available for engaging in action (as action makes people free). Free from the realm of basic needs, of daily urgencies, of survival. But how can we free ourselves from this in societies where most of the people live day to day on the edge? Where being above the line of survival is a dream, when not almost a luxury? It would seem that schools, in these contexts, have chosen not to free us but to abstract us, to shelter us and absorb us into evasive passive contemplation, which prevents action. On the other hand, today, leisure is associated with mere amusement, with distraction, or, in Debord's (2003)2 terms, with spectacle. Today's school is not a place to exercise creative leisure but to be functional, to become operative, so as not to be "wasting time."

How do schools lead us to evade reality, or at least prevent us from a comprehensive understanding of it? By radically fragmenting reality into watertight spaces unrelated to each other, setting boundaries that clearly outline that what is inside and what is outside are two different things that don’t interact, dialogue, or contaminate each other.

Therefore, there is a misunderstanding that schools can only be such by isolating themselves behind walls. They become schools without environment, without context. Infrastructures not attached to a territory or a community. Protective bubbles, blank pages to be filled with homework. And then there are cities without schools, as to enter the school is to leave the city, and vice versa. The boundary of what we mean by schools is the key, and that is a spatial problem.

Free time is linked to free space: the public space. Careri (2016)3 says that it is necessary to "waste time to gain space." But in these contexts where the concept of citizenship is so fragile, does public space even exist? Delgado (2011)4 tells us that it doesn’t, that it is purely ideological. And moreover, does publicness exist in cities like ours, which are mostly self-produced?

These are some of the reflections that give rise to Extramuros– Outside the Walls.

Curatorial Concept

Background

Extramuros proposes an action-research based process to understand the nature of limits/boundaries between educational spaces and their surroundings, and to act upon them, stimulating reflection on the need to dissolve/soften those boundaries and turn them into habitable in-between spaces capable of fostering dialogues between the inside-outside, the public-private, children-citizens, etc.

The concept of Extramuros arises in Lima, derived from the urban regeneration projects we develop in popular neighborhoods, where we always, at some point, end up running into a blind wall. Behind these walls, there is usually an enclosed school or public infrastructure.5 The research that accompanies our projects led us to understand that this noticeable presence of walls and fences in the city was both a product of the crisis of the public—expressed in a growing distrust and individualism within society—and one of the very conditions that produced it.6 Indeed, we are almost incapable of conceiving and building open public infrastructures: schools, universities, museums, sports stadiums—everything is walled in.

From my organization Espacio Residual, we have been working on a first pilot project in the neighborhood of Año Nuevo,7 in the Comas district of Lima. Here, we found relationships between the abandonment of public space, the construction of walls, and the fear of crime.8 The project9 (2019-2023) has been progressively dissolving the perimeter walls that have outlined an unsafe neighborhood with alley-streets with no social life or eyes on the street. Through the integration of the park and the school (Colegio Libertad), we have seen a reconnection between the neighbors, students, teachers, and the school administration.

Given that this is a common issue in many Latin American cities, it seemed appropriate to extend the reflection (which I summarize below in seven bullets) outside of Lima.

Places and participants

To this end, we convened three teams from three different cities to approach this issue with different nuances.

In Lima, with Michele and Carmen from Díadia Arquitectura, we share an interest in children in urban processes, and we had recently worked together in Espacios Revelados Lima,10 where they installed a playful piece called AAAAAA on a bridge in the city’s historic center.11 It was an ephemeral installation, so, it was dismantled at the end of the event. Moving it to Año Nuevo seemed like a great way to give it a new life. The challenge was to place the piece on the park so that it would be a kind of part of the school inviting students to go outside, erasing the boundaries imposed by the perimeter wall along the way. AAAAAA was turned into a cube that ended up installed in the center of the park, full of children playing around it, climbing up and down, waiting for the next stages of consolidation of the project.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

In Bogota, a city that has much in common with Lima, there is Jorge Raedó, a "master" in education, architecture, and childhood; he is a weaver of international networks on the subject (in which he has the recurring kindness to include me), and the founder and organizer of Ludantia12 and other such powerful initiatives. And there is also Fabiola Uribe with her initiative Lunárquicos, who has been doing excellent architectural work with children in schools for a long time. Fortunately, the both are a couple and share projects. Some time ago, we had talked about the problem of school walls in regard to my research, and they told me that many similar things were happening in Bogota. The challenge with them was to find a school enclosed by a wall or fence, among those they already had contact with. Almost immediately, they pointed out IPARM, which is surrounded not by one but by two fences: it is a school enclosed inside a university that is itself enclosed a well. They ended up creating playful fences in which they re-signified the fences of the other school with gigantographs of the children's drawings.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

In Quito, there is a generation of young architects doing very powerful projects with the landscape and local materials and construction techniques. Daniel and Marie’s La Cabina de La Curiosidad is a quite peculiar office. Their work mixes the artistic, the social and the environmental with design, in a creative and poetical way. They’re a team that I believe is capable of responding intelligently to any challenges presented. It seemed to me that they would do well working with children, but on another scale. In contrast to the other two teams, they would work on the relationship between the city and the landscape, because just like schools, our cities also close in and deny their environment. The Museum of Water, with whom they had been working, has a high impact on its territory, promoting a better relationship between the city and the natural environment. As a cultural-educational infrastructure, it was linked to schools, and it could be pointed as a rather positive case, not of confinement but of openness. The contraption they built as an observatory is a bridge that connects the city with its outside walls.

The coordination and integration meetings for all three projects flowed quite well. I believe the results point to a comprehensive and approximate reflection on the issue raised.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Marie Combette. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Marie Combette. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Architecture and daily life

Walls / Boundaries

The sites chosen for the three projects present physical or virtual walls that isolate the educational and/or cultural infrastructures from their surroundings.

In Lima, the school perimeter is a blind wall that is both a product and a producer of insecurity—a symbol of a generalized problem throughout the city. The project invites to come out of the enclosure by building an open classroom in the public space. The wall is not dissolved physically, as the project does not intervene the wall, but it invites the bodies (of boys and girls) to cross it constantly with an enticing objective outside of it (before, there was no reason to cross to the park), which points towards a dissolution. AAAAAA in the park creates the conditions so that, later on, the school wall can be removed and replaced by a playful fence that allows visibility across it, towards the street.

In Bogota, the school and university fences produce an urban "Russian doll": a fence inside a fence surrounded by a high-traffic freeway, creating an isolating triple border. In this case, the project does not seek to eliminate them either, but to understand them collectively, to make them visible, to make them appear, to reflect on them as an object and as a process, and to make their representation (children's drawings) an inhabitable space, or rather, a playable one.

In Quito, the edge of the city, disconnected from its natural environment, can be understood as a great invisible wall. The Museum appears as an example of a physically open space (a transparent SUM from which the entire hillsides of the city can be seen, with an attached small square like an urban terrace), but especially, its use of space and social function in the territory is remarkable. The project invites us to re-acquaint ourselves with the landscape-territory by building a lookout from the sensitivity. A small device creates a connecting bridge to show that what we believe to be distant and alien is actually close and common, thus, worthy of being cared for.

Children

The other transversal theme of the three projects is, as mentioned, working directly with children. Lima focused on neighborhood imaginaries and space in relation to the body. Bogota focused on the meaning of boundary / limit, and Quito on the exploration of the natural environment.

In Lima, we worked with 4th-grade children of an elementary school (9 years old), who live in the same neighborhood, in precarious and highly vulnerable conditions, with an educational infrastructure in terrible conditions. They participated through their bodies and movement as producers of public space. In the process, they forged an important bond with the Díadia team, committing themselves to continue participating in future stages.

In Bogota, schoolchildren aged from six to eight years old participated in the first stage, collectively reimagining the spatial boundaries of their school in the city through drawings; and then children from the kindergarten participated in the second stage by appropriating the banner structures with the previous drawings, generating habitable spaces.

In Quito, boys and girls from different parts of the city became guardians of the territory, working with a series of observation devices and multiple sensorial stimuli. The contraption built remains in the museum to continue connecting many more children with the territory, promoting a playful way of inhabiting the landscape.

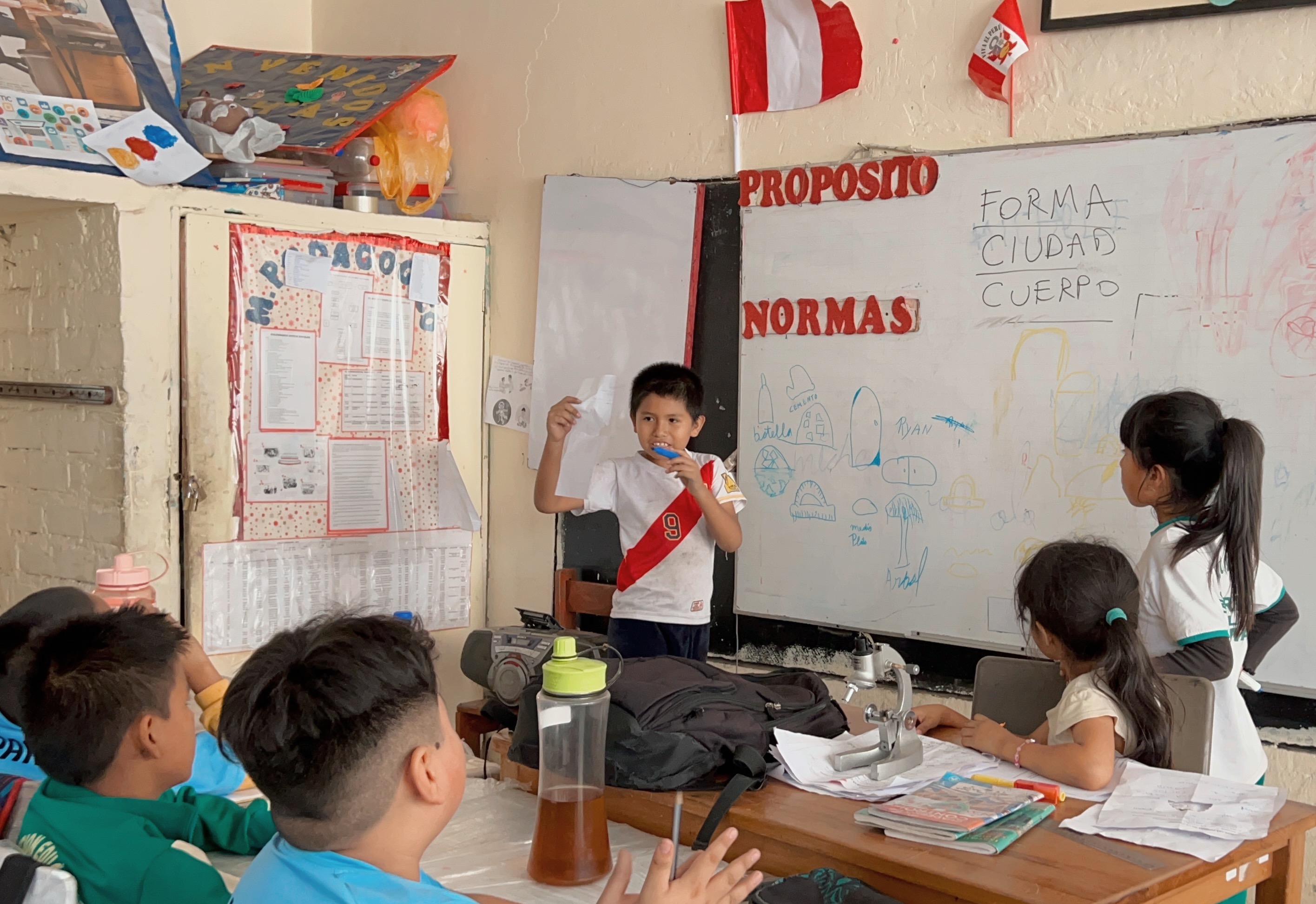

Talleres con niñxs del Colegio La Libertad.

Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Federico Rey. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Talleres junto a niñxs en Yaku Parque Museo del Agua.

Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Talleres con niñxs del Colegio La Libertad

Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Layers / Preexistances

In order for the projects to be carried out in such a short time, it was essential to approach them with the palimpsest logic of overlapping stories. The three teams are well aware that the city is not a blank page, so none of them planned to start from scratch, but rather to superimpose themselves on what was already happening.

In Lima, Díadia installed a pre-existing piece (AAAAAA) in a pre-existing project (Extramuros Año Nuevo), adding a new layer to the work of Espacio Residual, to help in the understanding of the educational facility and the neighborhood as a single unit. Using the pre-established bonds with the neighborhood, they were able to enter and work directly with the school’s students and teachers, contributing to the continuity of the project.

In Bogotá, Lunárquicos worked with teachers with whom they had previously held workshops, to reflect on the limits of the school and think about how they could restore their link with the city. They overlay a work onto another, adding a new layer to the story.

In Quito, La Cabina de la Curiosidad built upon the work of the Museum of Water, with whom they had already been working with the aim of promoting a better relationship with the natural landscape, to understand the city and its surroundings as a unit to be recovered. They contributed to the Museum's work and the museum supported them back with theirs; it was a collaborative and cooperative dynamic.

All urban projects are, in some way, homages to pre-existence.

Participation, coordination, and conflict

Extramuros is about processes that produce spaces, rather than artistic works on the public space. These processes have the participation of children at the center, around whom all other actors are integrated. To carry out their processes, the three projects applied different methodologies and tools, such as workshops, walks, drawings, models, performances, and so on. For this, they had to carry out a series of institutional coordination arrangements on each step, not without conflicts.

In Lima, the school principal gave all the necessary permissions, the assistant principal was in charge of the logistics of the whole process, and the teacher was involved in working directly with the children. An accident with the master builder delayed the installation of the piece in the park, so it had to remain inside the school longer than necessary. It then become a play temptation that could put those who used it at risk. On the other hand, the project helped to improve the relations between the neighbors and the school authorities.

In Bogota, the principal approved the project but the teacher didn’t get involved, she merely "lent" the children. Halfway into the process, the kids were forbidden to go beyond the fence for fear that something could happen to them (it was a time of student protests and repression), let alone intervene. The importance and intangibility of the fence became evident. The denial reached the point of forcing the team to look for another school to continue with the project, and so it was moved to the adjoining kindergarten. New workshops had to be held, but finally the whole process managed to be integrated.

In Quito, the work was less "self-managed," as it was done in direct collaboration with the Museum’s cultural programming and education department. As this is a rather formal institution, they facilitated the process and achieved a massive and heterogeneous participation.

Outside

Inside: the interior, the inner, the private, the habitable built space, the opaque, the secret, the predictable, the structural clarity, the home, the actors. Outside: the exterior, the public, the non-built and non-habitable space, the transparent, total exposure, the unstable, the casual and indeterminate, the street, the characters. If the inside is the space of the structure, the outside is the space of the event (Delgado, 2004).14

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Daniel Moreno Flores. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

The projects conveyed in Extramuros are a provocation to go outside the enclosure of the home, the school, the university, the museum, the city, questioning the deeply rooted idea in today’s imagination that inside we are safe and outside everything is dangerous. We must go through the walls, because outside, in the street, in the neighborhood, in the territory, could be the school that really sets us free.

Another way of looking at it is that these projects question the inside/outside split to point out that, if we stick to that, there can be nothing in between, just a juncture, a line, a wall. By inhabiting the interstice, in-between spaces arise, bringing in the outside and taking the inside out, turning walls into a shoreline. In this way, they align with Van Eyck's vision of the city as an "open interior." The city as a big house, the house as a small city (Van Eyck, 2021).15

To produce these in-between spaces, children imagine what is outside, go out to meet it, and invite it in. Then they try to appropriate the outside, to turn it into an inside: thus, they turn the outside walls into the city.

Extramuros – Outside the Walls: to value the periphery, what is out of control, the foreign. To lose the fear of the outside.

EXTRAMUROS LIMA: LA LIBERTAD SCHOOL

Location: “La Libertad” School and Park, Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Peru.

Authors: Díadia Arquitectura - Carmen Omonte and Michele Albanelli.

Team:

- 4th grade students of the elementary school "La Libertad".

- 4th grade teacher of the elementary school "La Libertad": Andrés Trujillo.

- Principal of "La Libertad" School: Kleber Figueroa.

- Territorial coordinator of Espacio Residual for the Extramuros project: Rogelio García.

- Photos: Eleazar Cuadros, Díadia, Javier Vera.

The Classroom experience had four stages:

- Assesment as a team of the Año Nuevo neighborhood and La Libertad Park, a public space where an urban regeneration project is underway, aimed at producing playful, safe, healthy, and didactic public spaces.

Knowledge-sharing encounter in the institutional classroom: We held five workshops with the children and their teacher Andrés Trujillo. The questions that oriented this process were:

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

What is a classroom made of? We wanted to hear not only about physical imaginaries but also about affective, environmental, and social imaginaries. The process revealed that a classroom is made of its place in the body: through corporal cartographies, we reviewed the affective physical relationships between the body, the home, the neighborhood, and the school. From this experience, the biggest personal and political revelation was that, almost unanimously, the children expressed that "the school is in the heart," even though the school itself is crossed by difficult material and institutional conditions such as precariousness and violence, as it located in a popular neighborhood with high rates of robbery and domestic abuse. It also came up that a classroom in made from its teachers, to learn about "walls." We shared some references such as Lima’s first kindergarten, initiated by the pioneer of Peruvian pre-school education Emilia Barcia Boniffatti in Lima’s La Reserva Park: "Without walls, with children, and with a teacher!"—the kids exclaimed.

How do we imagine, from our body, our relationships with learning? Sharing Merleau-Ponty's reflections, we consider that we know the world to the extent that our body is in it, placed with others in a given space and time. It was important to establish a reflexive level for the study of La Libertad School and the Año Nuevo neighborhood through the body, so this invited us to work going in and out of the institutional classroom and the school, sometimes using projective models, going outside of formal constructs regarding the body. "In my model, can you be laying down or slipping?" were some of the children's questions.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

- Collectively producing public space: Adapting the AAAAAA spatial installation (6 arches) to La Libertad Park did not mean installing it following the previous Balta Bridge project, where there was constant passer-by public. Here, the challenge was to build socially with the classroom’s children, the teacher and the principal, the stages to encourage a reviewing of the body from other terms; to encourage freeing it from the modern canons that built a body surrounded by walls such as individualism and distrust in the other. Physically, we sought to configure the space as the actual classroom of the children, but with another materiality: four arches.

- Celebrating: On October 13, 2023, we made the symbolic delivery of "Un Aula de Arcos como Andamio para el Aprendizaje en Año Nuevo (AAAA)" [A Classroom of Arches as a Scaffolding for Learning in Año Nuevo] to the children and the teacher, Andrés. During the event, together as a community, we recalled Article 31 of the Rights of Children: "...to acknowledge the right of all children to rest, play, and leisure activities appropriate to their age..." Since then, AAAA is a classroom for meeting and learning about how we can live together playing as a community.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

Proyecto: La Escuela Libertad. Año Nuevo, Comas, Lima, Perú.

Fotografía: Eleazar Cuadros. Cortesía: DIADIA Arquitectura.

EXTRAMUROS BOGOTÁ: (UN)FENCED FENCE

Location: Colegio IPARM, Bogotá, Colombia.

Authors: Lunárquicos - Fabiola Uribe & Jorge Raedó.

Team:

- School students.

- Kindergarten students.

- Teachers from IPARM school.

- Principal of IPARM school.

- Photos: Jorge Raedó.

What do children in Bogota think about the enclosures that separate and isolate residential, educational, and institutional areas? Lifting fences is a practice established in the late 1990s in the city as a "security guarantee," which resulted in the separation of the private from the public.

We collaborated with a group of 6 and 7 year-old students from the Instituto Pedagógico Arturo Ramírez Montúfar (IPARM) (eleven sessions), and with two groups of 4 and 5 year-olds from the Kindergarten (two sessions) of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá. The campus is inspired by the garden city and functions as an (enclosed) green island within the city. IPARM used to delimit its space with small bushes and low walls until the 1990s. It then built a metal chain-link fence around it to provide "security," which transformed it into an island within an island.

The educational proposal consisted of three stages:

I. Research: Understanding the concept of boundary.

The process began with activities to understand the boundary as a concept: the body, the classroom, the school, the campus, and the city. The children learned to recognize the different types of boundaries that exist: prohibitive, natural, imaginary, built. The latter were valued as essential to guarantee security, tranquility, and to delimit spaces that protect them "from the other." Then the students went to the campus boundary and represented the space in two dimensions: they painted the depth planes and understood the characteristics of the topological and the constructed boundaries.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

II. Formulation: Collective construction of criteria to arrive at the artistic proposal.

Individual creative sessions to imagine alternatives to the iron mesh that encloses the campus, in the area where the new school building will stand. They proposed high fences, closed walls, concertina wires, and intimidating laser beams to scare away "the others." The boundary was a divisive object. To stimulate new proposals, we reformulated the question: What do I want to see in the distance through the classroom window of the new school? In pairs and through drawings, they saw themselves as spectators and inhabitants of the boundaries. Thus emerged trees, flowers, birds, airplanes, balloons, animals, etc. The "enclosure fence" was banished, the boundary didn’t seem necessary anymore. Their drawings merged the schoolyard with its natural environment.

III. Installation mounting: Execution and staging.

The students brought ten banners with their printed drawings to the campus boundary to leave them as a spatial installation. Administrative problems prevented the mounting. We then installed the ten banners on the boundary separating the Kindergarten from the area where the new school will be built. The installation was erected on the lawn on an orthogonal layout that allows creating mobile and changing spaces. After becoming familiar with the concept of boundary, two groups of Kindergarten students painted their boundaries—the mother's womb, their body, the classroom, the landscape they see—on new banners that were added to the spatial installation. They also planted seeds in the lawn where the installation is placed. In this way, a garden will remain when the banners are removed.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Federico Rey. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Federico Rey. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Federico Rey. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Federico Rey. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Federico Rey. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Federico Rey. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

Proyecto: Valla (des)vallada. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fotografía: Jorge Raedó. Cortesía: Jorge Raedó y Fabiola Uribe.

EXTRAMUROS QUITO: GUARDIANS OF THE TERRITORY

Location: Yaku Park Museum of Water, Quito, Ecuador.

Authors: La Cabina de la Curiosidad - Marie Combette & Daniel Moreno Flores.

Team:

- Participants in the workshops.

- Interns: Marianne Letessier / Samuel Dano.

- Educational mediator: Andrea Jacome / Mediation intern: Benjamín Rivadeneira.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Daniel Moreno Flores. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Daniel Moreno Flores. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Daniel Moreno Flores. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Daniel Moreno Flores. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Daniel Moreno Flores. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Proyecto: Guardianes del territorio. Quito, Ecuador.

Fotografía: Daniel Moreno Flores. Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

It was a space for meeting, observation, assimilation and territorial learning with 25 children aged 8 to 11 years-old from the city of Quito in Ecuador.

We held a six-session workshop to consolidate the idea of children becoming "guardians of the territory." It is an invitation to acknowledge the greatness of the place where we live: the Andes, a territory with different ecosystems, mountains, snow-capped mountains, rivers, and other living beings.

We accompanied the children in a slow process of geographic-ecological assimilation while we played and learned together. It was a peaceful space, where the energy was focused on the proposed activities. The children were outside their educational facilities, as the program took place in the Yaku Park Museum of Water, in the neighborhood of El Placer in the city of Quito. We walked through the museum's native forest and experienced the splendid visual contact it has with the city and the mountains. We made a visit to the Rumipamba archaeological park to explore its different ecosystems and learn about the open-air creek that crosses it, which is a different condition from the rest of the city (90% of the creeks in Quito are covered).

The workshops with the children were creative cohesive environments among all kinds of inhabitants of this city, as they all came from different neighborhoods, far and near, allowing for social diversity and cultural richness.

Talleres junto a niñxs en Yaku Parque Museo del Agua.

Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Talleres junto a niñxs en Yaku Parque Museo del Agua.

Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Talleres junto a niñxs en Yaku Parque Museo del Agua.

Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Talleres junto a niñxs en Yaku Parque Museo del Agua.

Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Talleres junto a niñxs en Yaku Parque Museo del Agua.

Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

Talleres junto a niñxs en Yaku Parque Museo del Agua.

Cortesía: La Cabina de la Curiosidad.

The children had a place to reflect and learn by doing, in the presence of the territory. The workshop encouraged dynamic activities, with movement, action, and displacements both outdoors and indoors. The inside as a space of containment, concentration and confluence.

While the outside is a living space, an open classroom that stimulates learning by touching reality with its diverse characteristics. Learning from macro ideas with large and distant scales, to assimilating proximity and the different details of plants and insects. The Extramuros project proposes to develop tools to generate bonds with the place where we live; it teaches and invites us to position ourselves as guardians of the territory, to take care of our habitats and live harmoniously with other beings.

The work in the workshops with the children was an invitation to let ourselves be surprised by what we usually don’t see, or moreover, ignore and don’t even figure. A series of simultaneous trips on different scales, which provided objective, compelling, and detailed information about the Andean geography. With a slow methodology of insistent observation and attentive discovery, we internalize what we see and what we do through the experience of the outside, immersed in the territory: observing the mountains, touching and smelling the plants, being close to the birds and insects. This experimenting leads us to empathize with an ecosystem that requires care and protection, one that all we human beings are part of.