Providing curatorial accompaniment for the projects of Benvenuto Chavajay, María José Machado Gutiérrez, and Jessica Briceño Cisneros posed a conceptual and practical challenge. It implied synchronizing our remote meetings and also understanding the relevance of their respective proposals, according to the specific circumstances in which they live and work. In all three cases, we departed from each artist’s criteria and the methodology designed to address the question posed; each had their own approach. Along the way, we found significant variations in the interests and procedures employed, especially regarding the pedagogical framework and the mechanisms of collaboration. But all of this remained subject to the premise of articulating art, pedagogy, and the community in a flexible way. The photographic and video documentation of the works carried out are the records of this experience.

Benvenuto Chavajay María José Machado Gutiérrez Jessica Briceño Cisneros

Utopian Teaching

past

2022—II

12/01/2022 — 12/12/2022

by Félix Suazo

Body, pedagogy, and the public space—three notions that articulate LA ESCUELA___’s Classrooms program—gain a singular meaning in the propositions of Benvenuto Chavajay, Jessica Briceño Cisneros, and María José Machado Gutiérrez, framed in the project "Configuring Space: Body, Land, and Community."

For starters, not all pedagogies—especially those with ancestral roots—have their seat within the walls of educational institutions. Some of them require but a space for meeting and interaction; it can be the street, a natural site, or any situation that fosters collective learning. There, teaching is practical, spontaneous and intimate. Even in civil and educational environments where a large number of people cohabit, such as in towns, cities, or universities, interpersonal relationships and pedagogical approaches are limited to affinity groups with particular interests. In such conditions, dealing with others, with diversity, requires a sensitive pedagogy based on shared actions instead of unidirectional instructions. Doing things together, learning in complicity, does not mean homologizing differences but giving them a voice and a context in the global panorama.

The second aspect to bear in mind is the socialization strategy of these experiences and the way they relate to publicness. None of them seeks spectacularity but rather models of exchange according to the issue, place, and topic of interest they address. That is to say, they are proposed as instances of visibility regarding the people, communities, and specific environments where the proposals were developed—namely, the children of San Pedro La Laguna in Guatemala, disabled students of the University of Cuenca in Ecuador, and the participants of the biomaterials workshop in Valdivia, Chile. They all address specific interlocutors, ranging from many to a few, always in physical and conceptual connection to a collective learning experience.

Hence, the political relevance and ethical dimension of each of these gestures, which were closely linked to the individuals and instances that participated in these experiences. Here, face-to-face and hand-to-hand, at the very core of the relationships and mutual respect, the meaning was dispersed by contact.

Having said that, the proposals of Benvenuto Chavajay, Jessica Briceño Cisneros and María José Machado Gutiérrez, in the framework of the Classrooms program of LA ESCUELA___, sought to make their artistic purposes compatible with the contexts and circumstances where each of them is based. The utopian teaching they aim at does not imply the redemption of an unspecific other but aims at empowering an empathetic bond with each person, just as they are.

Sagrado

Only what is sown is harvested. Nothing is discarded, not even the kernels of corn that unintendedly jump out of their packaging or those scattered capriciously on the sidewalks. Everything is food, an essential nutrient for the corn people who still live, under the guidance of their ancestors, in the town of Tz'utujil in San Pedro La Laguna, south of Lake Atitlán, department of Sololá, in Guatemala. This is where the artist Anuto Chavajay Ixtela, also known as Benvenuto Chavajay, was born. He frequently returns to his village, where he reconnects with his family and friends.

He also meets with the children and walks with them, collecting the scattered kernels they find on their way, in an act of collective learning and memory. It all makes sense because, in the language of their ancestors, Tz'utujil—the town’s name—means 'corn flower.' Every grain of corn recovered is a syllable of the native alphabet and a symbol of the matter that gives body and roots to more than one hundred thousand people.

Benvenuto practices a ritual pedagogy, whose classroom is nature and its goodness. He talks to the stones, to his ancestors, and performs a sacred activity unnamed among the Tz'utujil, which in the West is known as ‘art.’

Kintsugi

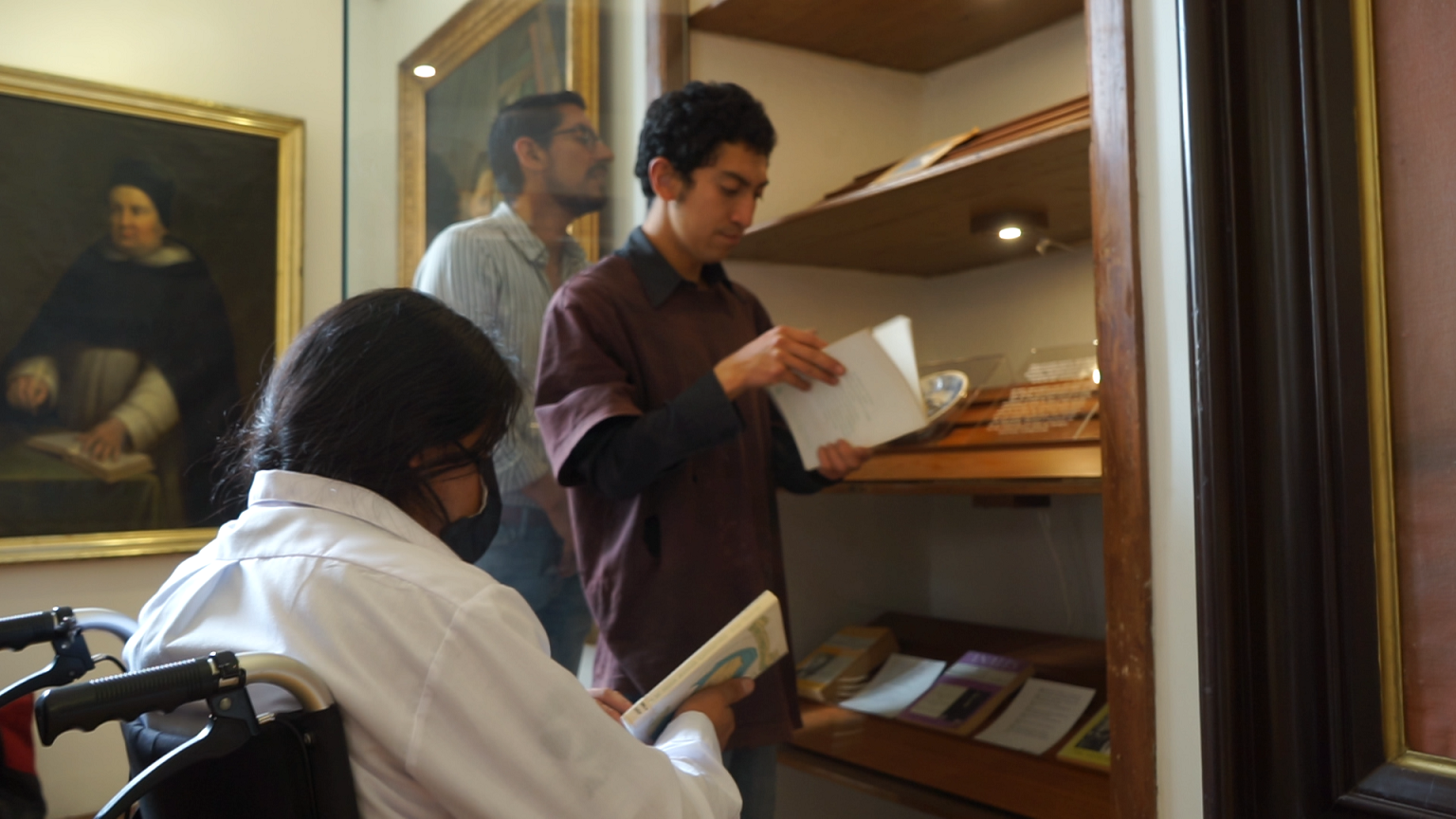

Every person is different, yet we all share one common condition: humanness. This includes our physical and mental fractures—some more visible than others, some more dramatic than others. In short, we all carry around some form of fracture or disability, even though, in the social reading of the matter, only the most explicit cases are recognized, and they are treated as stigmata. But nothing is really hideous or irreparable if approached from the human condition. That is the metaphor contained in the kintsugi plate sutured with gold splices used by María José Machado Gutiérrez in her homonymous project, conceived to make visible the issue of people with some kind of disability—hearing, motor, psychological, and so on—in Ecuador. Beyond the statistics, there are faces, gestures, voices; there are lives.

After an intense effort with students, organizations, and authorities that converge at the University of Cuenca, María José managed to thread this experience into a video and to have an allusive commemorative plaque installed in the University Museum. Both gestures seek to restore visibility to the problem of disability without instrumentalizing the issue, amplifying the presence of these often-omitted people due to their condition. The video combines the words and bodies of three students from the University of Cuenca. The plaque summarizes the rates of disability.

Temporales

The origin and destiny of all organic life are linked to water. The first life forms gestated in it, and the future survival of plants, animals, and humans depends on it. Water has been a persistent motif in the work of Jessica Briceño Cisneros. Water containers (fountains, ponds, tanks, pools) and floating vehicles (boats) have occupied her attention. Water architecture and biomaterials are also among her main interests.

Based on these premises, the artist proposed an experience that combined art, pedagogy, and the public space in Valdivia, a river city founded in 1552 by Pedro Valdivia. Located at the confluence of several rivers, it was considered "the key to the southern sea" by the Spanish conquistadors due to its strategic location on the coast of the Pacific Ocean.

In this enclave, Jessica's work unfolded in several stages. First, a biomaterials workshop developed in four sessions, jointly convened by the collaborative space COMA, the biomaterials laboratory LABVA, the Estudio de Campo foundation, and LA ESCUELA___. Some of the activities carried out in the workshop were gathering the materials, preparing the components, filling molds, and supervising the drying process.

The second part was a nautical event with the boats made in the workshop. The boats were taken to one of the river basins in the area, as a metaphor for the return and reunion of the natural with nature.

Statements

Sagrado

by Benvenuto Chavajay

To speak or to think of corn is to think and speak of the word SACRED. According to the Popol Wuj, sacred is the human condition. In the Mayan / Indigenous cosmovision and ancestry, corn is the most sacred food and element; from childhood, we are instilled respect for the corn kernel (Ja ixiim k'o ruxajaniil = 'aura of sacrosanct'). Corn cannot be lying around on the ground, it must be collected. The statement “corn cannot be spilled,” is stronger than that of the Lord’s Prayer in the Mayan / Indigenous cosmovision.

The meaning of collecting kernels in the streets is to instill an awareness in younger generations of the importance and sacredness of corn for the human condition; it is the sacred food. Collecting the corn spilled in the streets, taking it to the mountain to bury, is to return it to its SACRED condition.

The Popol Wuj relates that the two twins, before the trip to Xibalba, planted a stick in the center of the house; they told Ixmucane: "grandmother, if this stick does not sprout, we are definitely dead, and if it sprouts, shout, sing, dance, and cry for joy because we are alive."

To learn more about the project, click here.

Kintsugi

by María José Machado Gutiérrez.

Working from art in community contexts can be a risky action if we are not aware of the possibility of cultural extractivism. It is an exercise that must be cared for with affection and respect, even more so when we chose to work with the community of students with disabilities at the University of Cuenca. Our experience was carried out together with the university research group KALEIDOS.

Kintsugi appears to be a simple interview exercise, but it proposes an option for creating real bonds with the inter-institutional situations that execute and design transformative plans and programs from research, dialogues, and strategies attuned with the needs of the “pariahs of normativity,” of what has been naturalized by social consensus as ‘normal’ within a capitalist system according to completely globalized aesthetic parameters, as well as to offer a participatory option for those who will be part of the student community.

Kintsugi, as a Japanese technique and philosophy, names the interaction of reconstructing the unusable or broken from philosophy:

— Rehabilitating the broken: (people with disabilities)

— Restoring broken relationships: (institutions and human groups)

— Re-signifying what seems unusable: (people with disabilities in an educational context)

— To give a new value from new values: (the creative act)

Public art, museums, the institutionalized spaces for art, have proven to be those that, over the years, own the narratives of power and are allies of what the systems have needed to tell. Therefore, intervening the main hall of the University Museum with statistics and a plaque that names what the University had never named is for us an act of social resistance from the educational community.

Not all communities are viewed with the expectation of observation; many communities exist from invisible actions or from spaces that cannot be exposed. That does not mean that they do not exist. Art can offer the possibility of reinventing the ways of looking at them from their dynamics and codes; they cannot be denied social participation, but not from the concepts of the social voyeur, the researcher voyeur, or the cultural voyeur. Thus, this project seeks to decode the named; it does not at all intend to seek an answer or a conclusion but to question those who look at it from virtuality or from the territory that will remain in the history of the University Museum.

To learn more about the project, click here.

Temporales

by Jessica Briceño Cisneros

This workshop was an instance of meeting and learning around the construction of small-scale boats, using organic-based polymers and locally collected materials from the city of Valdivia. The space was open to the public for experimenting and learning about biomaterial recipes with natural residues from the area. We sought to test different mixtures used to create small boats and see whether they would sink, float, or sail for a time determined by their own degradation. In addition to vegetable- and animal-based binders, we used local residues such as sawdust from native trees, mussel shells, leaves, eggshells, among others.

The boats were made in groups, using different techniques such as mold casting, modeling, or making them freely. We had the support of the Laboratorio Biomaterial de Valdivia—LABVA—to reach different results in the workshop.

In Chile, ‘temporal’ also means ‘storm,’ usually of marine origin. Here, we used it in two of its meanings: in reference to the sea, to water, to the boats, also as a reference to the survival time of the fabrications we created during this encounter.

To learn more about the project, click here.