Nicolás Paris: For a long time I was a teacher in a rural school on the edge of the Eastern Plains, with the Orinoquia in Colombia. Almost ten years after that experience, I made the decision to change to art and work as an artist, with the conviction and desire to combine the experience I had as a teacher in a rural school with artistic research. At that moment, without knowing much about art history, I came across your work and there was (and still is) something that moved me and really motivated me. So here I am, in an almost confessional way; I always cite you as one of my references, because from my point of view I found in your work that you were perhaps, I dare say, the first artist in Colombia who was able to do her practice as an artist outside the studio, outside the artist's studio, and you began to engage and work fully with or among the institution. I think there is a difference between my experience and what I know of your work from that time, and that is that I like to think that working as an artist (and researching how we learn) are not parallel situations, but in my case I try to make them the same. I would like to ask you about this: do you see or understand artistic practice and research in education as something parallel, or how do they nourish each other in your case, how do they feed each other?

The Museum as a Thinking Protocol

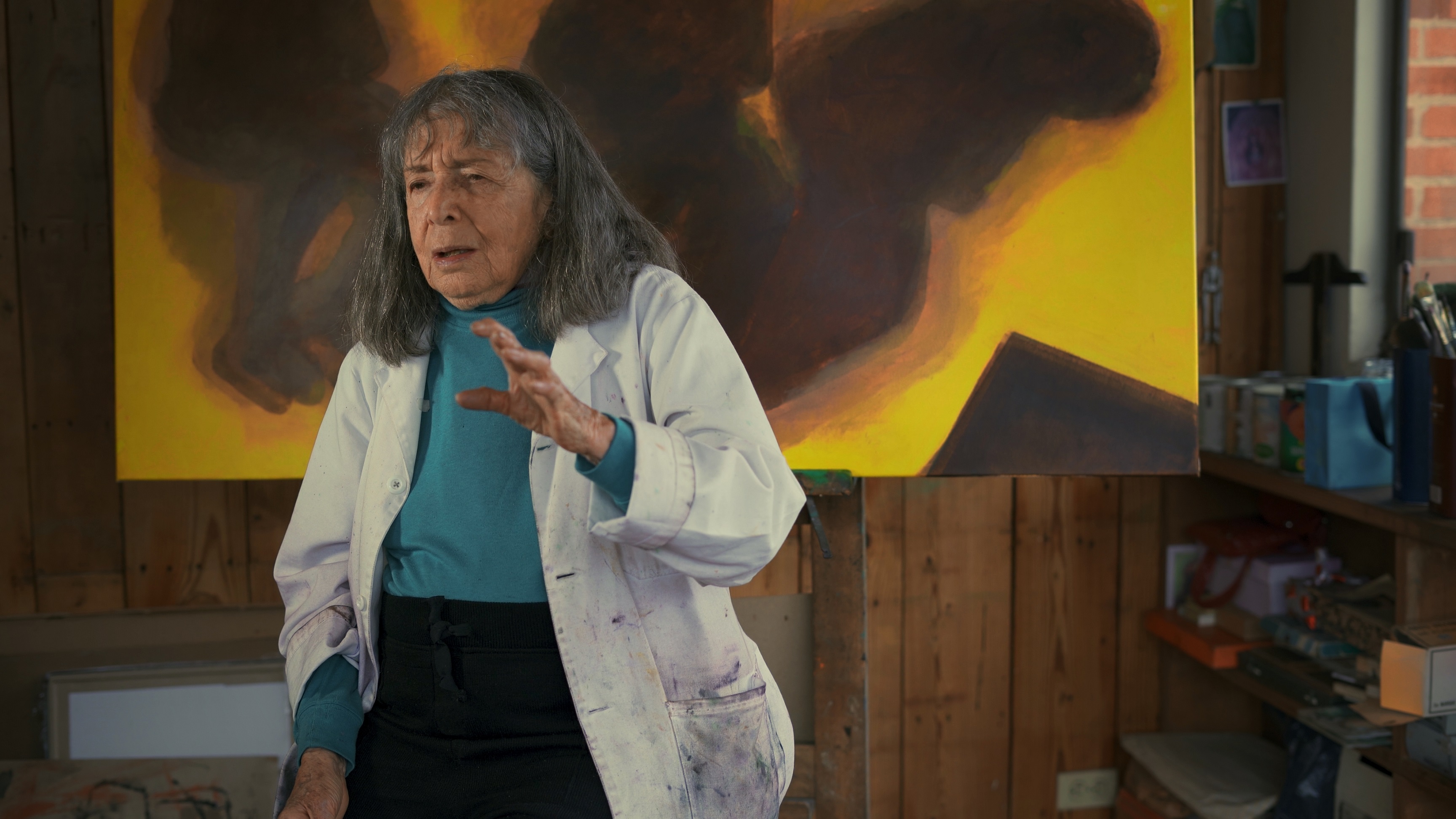

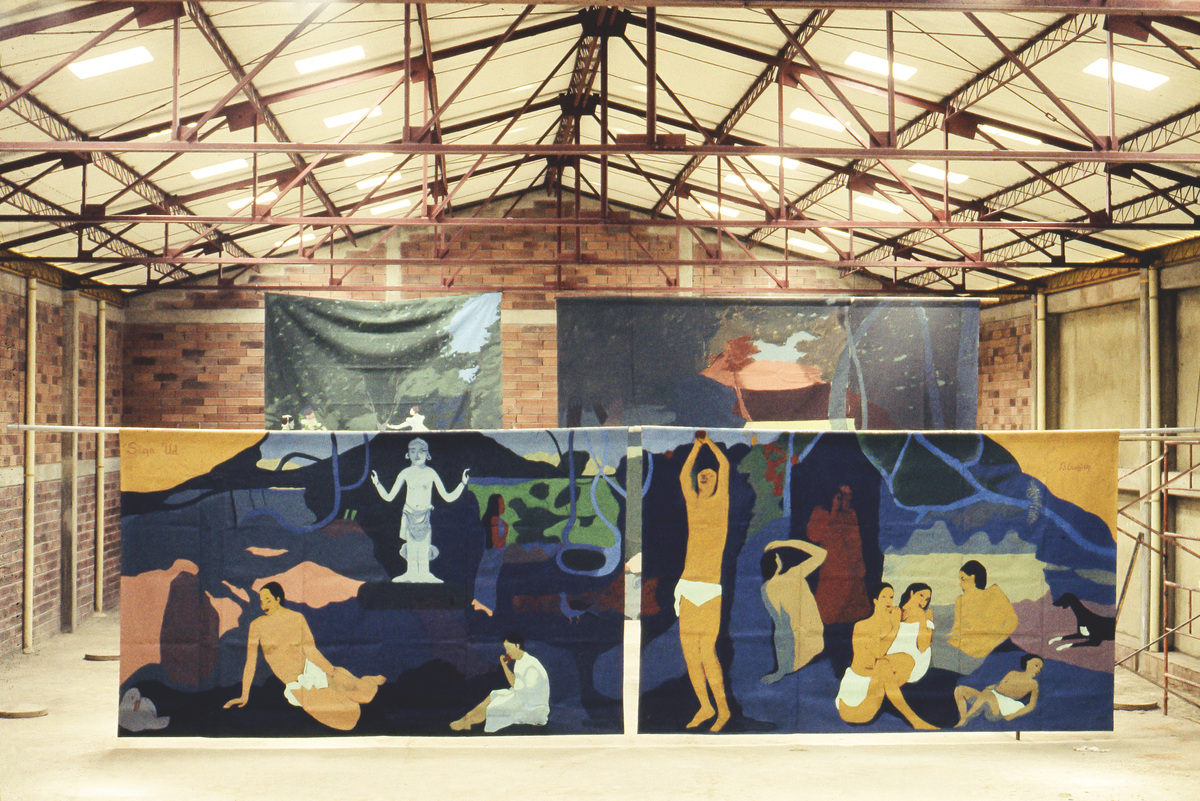

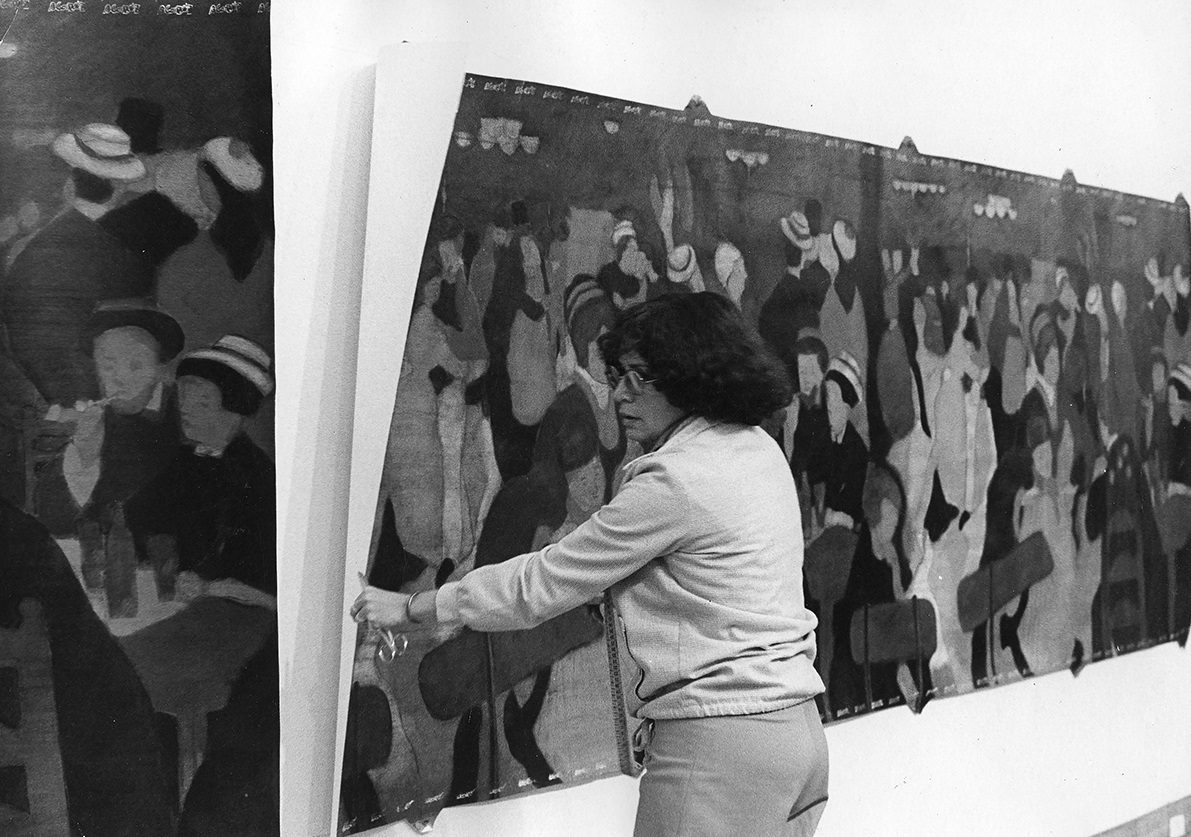

Nicolás Paris talks with artist Beatriz González about her involvement with museums as learning devices, the strategies and protocols developed during the time she spent in different education departments of cultural institutions in Colombia, as well as that which, according to her, is impossible to teach: painting.

Beatriz González is considered one of the most influential figures in the Colombian art scene due to her incisive and lucid stance as a chronicler of her country's recent history. In addition to her extensive artistic career, González developed an important curatorial and pedagogical work from her role as director of the Education Department of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá in the 1970s. Similarly, through her participation in exhibition and research projects in several national institutions, she worked toward conceiving museums and exhibitions as spaces for transmitting knowledge, where the public was engaged as an active interlocutor in a direct and frank dialogue.

Beatriz González: Yeah, I really found education because it was part of my family, even though I didn't like teaching. I found that there were some genes in my family that were actually related to education. So I started teaching in a school, like many artists do, but there is something that I was very clear about, and I always have been, that you cannot teach painting; that is, to be an artist is to make sculptures, to make paintings, to make things, and it turns out that I knew that very well. I teach, I don't know, you never learn to paint. That was my thesis.

Later, at the University of the Andes with Marta Traba, I thought it was possible to teach how to think; that the artists, the little artists who were in the schools, who were used to having teachers tell them, "How beautiful, how well you paint!" It was no longer a question of that, but simply of teaching them to think about what art is. It seems to me, for example, that when I came to the Museum of Modern Art and started teaching in schools, I used to say, "How awful! These kids come in screaming and they don't know anything,” and then I'm yelling things at them because they can't hear, because of the noise. The show was Calder's, so I thought: I don't have to tell these girls who Calder is—how lazy. So I gave them a tour, but I told them: When you leave this place, if you notice how the leaves move in the stalk, you have understood Calder. And that to me, that reflection of mine, which is almost a philosophical reflection, satisfies me, still satisfies me. Because these girls, when they look at Calder, they will not say, I know who Calder is and Calder and his motives, no, they will see. So that is the identification of my being, as a person who teaches to appreciate art, because the great mystery is how a person in a museum approaches a work of art.

But not everybody has the information and not everybody should approach art that way; if you should not approach art, you stand in front of a painting and suddenly a little tiny thing, a root, a leaf or something causes you to see, ah, look, here it is! and then you get hooked. I am interested in how to get hooked, how to get people hooked on the appreciation of art, because it is not the erudite knowledge of art, it is not really what moves you to get hooked on art. So at that moment, when all the children that the mayor's office had sent to the Museum of Modern Art came in, I had to face them. Thousands of kids would come in and I would yell, I would teach them, but that wasn't it. Then I really realized what the problem was, the problem of appreciation, of being trapped in a work of art, in a museum. How do you get trapped? What makes you trapped? I said a long time ago that I would not teach painting. They said, Beatriz, why don't you come to the Andes or to the Tadeo to teach painting? No, painting cannot be taught in the first place, in the second place, you never know how to paint, I still paint and I have the knowledge, more of a taste for mixing colors, but how can you teach painting? It is impossible. When I'm 80 (and I'm over 80), I still don't want to teach painting, because it can't be taught.

What I want to tell you is that I've had worries, you can't call them worries, but worries about how a person approaches a work of art and how that approach makes you want to see more works and transforms your thinking.

I still have many concerns that I have not resolved, but I think that the approach to love a work of art is due to a mysterious phenomenon that makes your sensitivity, your eyes, your senses, go swimming in this immense sea that is the contemplation of the work of art. I am interested in contemplation.

I really like when you talk about how the viewer approaches the work. For me, this is important because it is not about trying to explain something, but about creating an environment in which the person feels comfortable, feels at ease, and perhaps contemplates, asking themselves how they can connect this experience of the work of art with their daily life. For example, if they are walking in a forest and they notice the leaves moving. I want to ask you about protocol and strategies, which are words you use a lot. What do you think might be some valuable strategies or protocols for learning and for learning to contemplate?

Yes, I like those two words a lot. I have to admit that I borrowed the word "protocol" from my metaphysics classes, which I took for three years with Danilo Cruz. Before each class, one of the assistants had to read the protocol of the previous class, and from there I adopted the word. When I started teaching the girls at school, they really wanted to do protocols. So I gave them crazy classes that had to do with Chaplin, Ramirez Villamizar, Picasso, those were the three subjects. Then the girls had to do a protocol, which is to protocol a chain of knowledge, so that they could really affirm what they had learned in my class. I still use the word protocol a lot in the study groups that we have.

I use protocol because it is like bringing back memories and making people reflect because in 15 days or eight days you have changed. So it was like inviting a reflection based on memory. I think that those three years with Danilo Cruz taught me how to think. My brain assimilated that I was one of the students of philosophy in the Andes, but I was a poor art student, but I think that philosophy helped me a lot to paint, to make my exercise as an artist. I think that not only for my meetings—because I don't teach classes anymore, but meetings of very dear people—when I talk about some texts in these meetings, I think that all this thinking comes out of me, but this thinking trained by the philosophy classes has even helped me to cook.

The other word was “strategy.”

I love strategies because strategies have to do with playing. A strategy is what am I going to do to get this person interested in art, so I make up strategies. For example, when I was a curator at the National Museum, I used to say to myself, you have to do the exhibition of so-and-so, who is coming.

So the first strategy I used was to take myself and say to people: if you have books on this subject, bring them, and we'll make a library, and we'll make a library. At the Museum of Modern Art we also had strategies, for example, one strategy was to see how the museum had the slides, and then Doris Salcedo or one of those people would organize the slides.

That was a strategy of knowledge, and the museum had a good set of slides, it was a tremendous mess, so they already had to research, they already had to see, and they had to see all the time the slide, all that, that was another strategy. It was not that you have to do it, no, but that you have to know what this set consists of, this treasure that the museum has.

I wanted to ask you about a strategy that I know you used with me, with these young artists that you work with in modern art, how you prepare the groups of students for the moment they arrive, how you prepare them before they come to the museum. It had to do with slides. I think you called them the Ante image.

I think that is one of the most interesting strategies that I have done, and I love it very much, because I noticed that so many schools come to museums to learn about the treasures that they have, to learn about the collections of the museum or the exhibitions of the museum. And then I thought that they should have a preview of the exhibition, of the paintings, of what they are going to see, so it is not "children, today we are going to take you to the Museum of Modern Art to see the Klee exhibition," no, they have a class and the class was taught by my students: Daniel Castro, Doris, well, many, Cortés, many young artists who were very important, good artists. What happens?

They (the children) already know what they are going to see, that is, they have a preimage, they already have it in their heads that they are going to see something and that they already know it. So they come to the museum already domesticated (because that can be a very nice word, domestication) and they pay more attention because they already know what they are going to see. And I am very grateful to my students, there were about 20 of them who helped me with this, and they were very happy, they were very happy to explain the exhibitions without seeing the exhibition and then finding it, meeting it and finding something they already knew.

I really like how you pose the relationship between the museum and the experience of looking at or being trapped in front of a work of art, always in relation to something that is happening outside before or after, when I go to the forest to see the leaves moving, or the previous preparation in a school classroom. So like the museum, maybe it's not just the exhibition, it's not just inside the museum, it's before and after the visit. And I really like how you bring up the idea of strategy in terms of making connections.

And continuing with the idea of making connections, I'm thinking about your method, your way of working. I like to think that an artist, for example, instead of leaving a series of finished works, what he really builds and shares is his working method. And I also like to think that because that working method is what can be replicated or learned from them, and what makes them change over time; when I follow or get interested in an artist's working method-and I'm going to connect this with an idea-as you already told us, and suddenly it's like in philosophy class, they would analyze a sentence, for example Plato's, over and over again, they would read it in all directions, and it was almost like they were starting to understand that sentence. I mean, like an image that you can look at, and at the same time you tell us that when you went to the museums, where you looked for the paintings that moved you the most, you would focus on that painting and you would repeat it and you would try to understand it again from many sides. I would almost say that this could be one of your working methods, even a scientific method, and you are already talking to us about philosophy, but I also know about your interest in mathematics, especially when you were studying. I would like to ask you how you relate the scientific method, the research method, to long learning.

I think it's like a light, like a curtain being drawn, I felt that way. Once I found a letter from my mother that said (I was in the first year of high school at the time): Beatriz lost arithmetic and geometry, but thank God she doesn't care and doesn't suffer. My mother was very hedonistic, but when I was in the third year of high school, the curtain came down, I was working on something related to algebra, and I invented an algebra formula, and the nun was amazed that I could have this intuition, and she had never seen a way to approach a little math problem.

So I think that's when I discovered that I was fascinated by mathematics and that before I hadn't paid attention to it because I had a reputation as an artist, it seems to me, I don't know if this art teacher was very good or what it was, because she made us paint, draw a tangerine in charcoal, I was in 5th grade, she put the tangerine, I drew it and she walked by and picked up the drawings. She looked at mine and she took the drawing and she said "an artist" so I was classified as an artist. But it was really the approach to something that I understood that I had to do, and without realizing it I was not making a work of art, but I was making a good drawing.

So I think all that mathematics, all that Danilo stuff, gave me a scientific mentality to approach an object through something called art, because not everybody approaches objects. You can approach objects, and everybody can approach objects, but the way you approach them is different.