Karen Bernedo: I wanted to begin by looking at the context in which the Yuyachkani project began. This year you are celebrating 51 years of creative work, during which you have navigated different social and political contexts, not only in Peru but also in Latin America. How does Yuyachkani’s proposal relate to group theater and pedagogy?

Dialoguing on Equal Terms with the Theatricalities of the World

11/07/2022

with Miguel Rubio Zapata

Karen Bernedo talks with Miguel Rubio Zapata about the beginnings of Yuyachkani, the role of pedagogy in the process of creating a community dramaturgy, the importance of the spectator in the construction of a scene, and the figure of the ‘dancing actor’: a performer that writes with the body.

Miguel Rubio Zapata (Lima, Peru, 1951) is a Theater director, founding member and director of Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani. He proposes a theater of creation and research based on material produced by actors. His experience is based on research into Peruvian culture and its application in contemporary artistic expressions. A sociology graduate from Universidad Particular Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1974), Rubio was given an honorary doctorate by Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA) at the University of Havana (2010).

Miguel Rubio Zapata: I think Yuyachkani emerged in a key period, which is by the middle of the 20th century. It was a fresh moment of cultural insurgency in Latin America and the Caribbean at the time—we are talking about the 1970s. It was a context in which many scenic proposals appeared looking to differentiate themselves from the hegemonic theater, that is to say, they were theater groups (or group theaters) that decided to make a more immediate theater, one that could dialogue with the time, with the social and political moment of a convulsive and hopeful Latin America.

We were coming from the Cuban Revolution, from May 1968, from the context of the Latin American literary boom, from the new Brazilian cinema, from the new song, and so on. I believe this was a moment when Latin America began looking inward and generating alternative production methods. And I think that the bond created with these new spectators who demanded a place as protagonists launched them into new spaces, new themes, stories, and characters. It was after this experience that we became aware of the need for a different pedagogical space, one that would be based on questions, which I believe is the one we maintain until now. Yuyachkani is not a pedagogical space where knowledge is transmitted with universal pretensions.

How is group theater linked to your theatrical pedagogical proposal?

Collective creation is by no means a method but a political attitude; it is an answer for the new moment, an answer to share knowledge or not-knowing, to be well. It is more about coming together as a collective to tell how from this place of questioning we can invent.

The word 'invention' is key because the old masters called upon us to invent a new theater suited for the time, which, in turn, demanded a response that went beyond the show that was being performed; it also had to have an educational response. This is the link with the group theater, that is, this nucleus that was like a family that meets to investigate together, not to create a show but to create a long-term artistic project. This nucleus uses the tool of collective creation as an attitude to gather diverse knowledge and create from an instance of questioning. This relationship between group theater and collective creation has resulted in a new actor.

Theater as an event was what mattered for these new relationships and, obviously, that faced us with generating a learning process, systematizing the learning in terms of dramaturgy, actors, and the production of ephemeral events that occur in the moment of the theatrical performance and then end. This is different from getting together to write a text and then shelve it. Or rather, the very notion of a 'text' changes, and so we understand the text as a texture, as weaving, as a loom, as writing in space.

I believe that this is a necessary cultural response to recover writings that come from dance, from ceramics, from the loom... In short, all this came together in this new mode of production, in this new space and confluence of groups who didn’t know each other but were nevertheless revolving around the same thing. I’m talking about Augusto Boal, for example: How important was his thinking, his theory of the Theater of the Oppressed!

You were saying that the seventies were a moment of a particular cultural horizon and meaning in which Latin American countries began to look at their history. Yuyachkani has always proposed a look at Andean theatricalities, which also implies a particular way of doing pedagogy.

It seems to me that Yuyachkani has also generated a process of systematizing and inventing exercises that can dialogue in that way. I also feel that it has influenced the way of organizing the event: just as in traditional festivities the space isn’t divided into a stage and spectators but actors and spectators participate in the same event, this bond has allowed us to think about dramaturgy.

We see the performance also as the organization of the action in the shared space, rather than as a text that is recited on a stage, where the spectator is there passively, consuming that which is supposedly important. I believe the encounter with these new spectators and spaces has also necessarily implied rethinking education and creating a statute of knowledge, organized in terms of these new relationships. This has been fundamental for creating an alternative pedagogy from that place, one that implies shaping and replicating the dialogues that we are finding with those new spectators.

Yuyachkani has a strong pedagogical component: every year you hold laboratories called desmontajes [disassemblings], which reveal some of the creative processes behind the performance; also each of the group’s members has found their own methodologies. Since when or where did you begin to systematize or become more aware of this?

Yuyachkani is like a stream that runs between two banks: one bank is community theater—which has to do with the experience as a community, in the neighborhoods, the trips to the regions, and so on—and the other is the experience that takes place in the theater hall, which is the theater laboratory itself, the technique. It is in the confluence of these two shores that we hold our dialogues and the process of systematizing the experience has to do with that as well.

In the late 1980s, Cuba's Casa de las Americas set out to create a school and summoned 11 groups from Latin America and the Caribbean to think about what a pedagogical project of Latin American scope would be like, one that would bring together all these local experiences. We had to think of a different school, proposed as a space for exchange and recognition of the diverse theatrical proposals that exist in Latin America. From that pedagogical context emerged the concept of desmontaje—disassembling—or the very practice of starting to become teachers.

What were these disassemblings like?

They consisted of dismantling the plays we made to look at the components: What were the elements? What were the sources? What was the process like? Now Yuyachkani has a product that is the result of the disassemblings, called ‘scenic conferences.’ It is a format that falls somewhere between the process and the result. In them, the actor and the actress come into the space with the spectators and tell how the process has been; when we find the question behind the performance—which is a key element—then begins the process of trying to answer it. So all the disassemblings are different because the plays are not presented as a predictable result, we dive into the performance and then systematize how the process was; that is why I use the word 'methodology' very carefully. Methodology could be understood as a theoretical apparatus with predictable results, but ours is rather based on the question, in order to understand theater as an operation.

There is a lot of back-and-forth learning in what you say. There is an exchange of knowledge with Andean cultures and their theatricalities and with the places that you go to. This exchange also happens with the spectator. What role does the spectator have in the back-and-forth learning in Yuyachkani's proposal?

The spectator is a fundamental agent of change. The awareness that spectators must be creators who use their imagination to complete what the scene proposes has been essential for rethinking all the ways of using space. It’s what Augusto Boal called the spectactor, that is, the spectator who becomes an actor. This spectator-actor has been fundamental, as well as Boal’s thinking. He points out that this proposal implies that theater can happen in any space—even in a theater hall—and that theater can be performed by anyone—even an actor.

One of Yuyachkani's recent projects talks about the school, where a graduation speech is a critique of the way we are taught history, the absences or the blames for absences, the issues, the pending debts... How can theater be an answer to the straitjacket that formal education sometimes wears?

That is an excellent question, also because oftentimes formal education understands theater from the established perspective, as hegemonic theater, not theater as a game, as invention, as a possibility for immediate response. This play has to do with a critique of the public school and how history is taught. The argument is based on a painting by Juan Luis Piani that has been widely studied because it allows seeing the absences from what it portrays: militaries, authorities, priests... but it does not include the liberation process and the preceding battles, the Indigenous presence, nor the afro-descendants. So, from a supposed graduation speech that a group of students gets together to write, we take up the questions: What are the absences? Who is not present there? And we have also worked on this piece with students from a public school.

In the 1970s, when you began, there was a spirit of generating revolutionary educational proposals and alternative counter-narratives to the hegemonic ones; now we are in a completely different moment, imbued with the paradigms of progress, development, and neoliberalism. Do you believe a decolonizing theater is possible at this time?

I look at the history of Yuyachkani and the history of Latin American theater and I see that we have not sufficiently confronted those ancient theatricalities, which are still present in traditions, sending us signals from the meaning of our native cultures. There has been a political response, but very much framed in the immediate, and I assume that Yuyachkani is part of that process, but there are a series of theatrical expressions from the native cultures that we need to integrate. This is what I call "the broken root."

There is a broken root as a consequence of the conquest, of the imposition and violence, which also has to do with literature—because writing does not arrive here as a way of communicating but as an imposition, as an exercise of power, as a way of ignoring those who were here before. The chroniclers of the conquest valued the expressions of native theatricality with Western categories, seeking to catalog them according to their resemblance to tragedy, comedy, drama, etc., disregarding other forms that I believe we have an obligation to recover.

What you say is very interesting because many of those pre-Hispanic dances have survived until today. This has to do with the transmission of knowledge that Diana Taylor talks about, which refers to how the body, the repertoire, transmits knowledge. Have you found this intuitive pedagogy in the travels you have made across Peru? In what ways is the body important for pedagogy in theater?

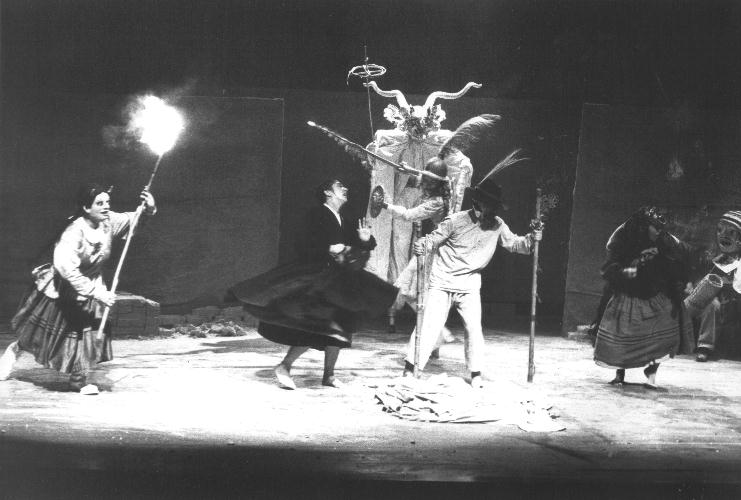

I think an appropriate category for a Peruvian or Latin American actor is that of a "dancing actor." I cannot think of an actor as a declaimer nor of a dancer as someone who simply dances because we have other forms of non-literary writing: we did not have literary writings in the pre-Hispanic world but we had other ways of writing: in murals, ceramics, textiles, and the body itself. These writings that are in the body and that are transmitted from generation to generation seem fundamental to me because a traditional dancer is not only releasing the body but is creating a memory with it. Many of those dances have implicit narratives and nothing of what is placed on the body—neither the steps, nor the dancing, nor the movements, nor the accessories—are merely decorative elements; on the contrary, they have to do with writing. Therefore, a dancing actor is an actor who also writes with the body, and that has been fundamental for me.

Do you think there is room for a meeting point between the formal academy and those more intuitive historical learning spaces that have passed from generation to generation? Is a dialogue between these two pedagogies and dimensions possible?

I believe this is a necessary dialogue and, in fact, we are doing it now. I can point to the very process of Yuyachkani, a self-managed, self-taught group that has generated an alternative pedagogical apparatus based on organized experience. Systematizing our experience has allowed many of us to teach in universities. This is interesting because our techniques are not meant to replicate something already known but are based on not knowing, they arise from the question of how to do; academia’s question comes from another place. Fifty years later, it seems to me that Yuyachkani's proposal has to do with the awareness of the need to organize this knowledge. Now we are developing a diploma project about Andean theatricality; we are going to carry out the first experience in Andahuaylas. Developing a diploma project is the beginning of entering into this more formal dialogue with academia.

Do you think it is possible to build a horizontal dialogue within an academic institution?

I think it’s difficult, but there are also sectors in academia that are valuing the knowledge of artist-researchers differently. If we value the knowledge generated in the classroom and the knowledge generated from experience, it seems to me that this is rather complementary, and that we should not foster a polarized bond. It is difficult if we approach each other with an opposing attitude, disregarding or invalidating one another; we should rather propose a dialogue.

It is a challenge to democratize teaching and learning spaces in theater, you yourselves are an example of this because, although you now teach in universities and conduct laboratories, you have also learned from great masters, masqueraders and dancers who do not necessarily come from formal education. As a final point, what would be another challenge for the teaching and learning of theater today?

I think the greatest challenge is to dialogue on equal terms with the theatricalities of the world. That is, to pursue the development of our singularity, and in that process, we must dialogue with everything that exists: from the Western theater tradition to Asian theater—which has also been quite influential—as well as with other unrecognized theatricalities linked to living native cultures that are treated as minor theatricalities.