Madeline Murphy Turner: I’d like to start by talking about educating from your perspective as a student. Around 1992, with the scholarship you won from the Ecoart exhibition, you went to the Venezuelan Amazon for the first time. How did the experience of learning with and from Yanomami, Yekuana and Piaroa communities impact your approach to education?

Education Is an Exchanging Process

In this interview for LA ESCUELA___, curator Madeline Murphy Turner talks with multidisciplinary artist Laura Anderson Barbata about her practice deeply connected to education, the creation of horizontal structures of dialogue and collaboration, and a commitment to artistic research as a method of accessing, recovering, and making visible histories erased by systems of oppression.

Laura Anderson Barbata: "Activando el conocimiento desde el cuerpo".

LA ESCUELA___ (Conversaciones, 2023).

Laura Anderson Barbata: I like how you phrase the question, speaking about my education from outside academia. This experience was incredibly important in my formation as an artist, beginning with the first encounter I had in the upper Orinoco. There was a Yekuana family, the Ortiz family, teaching the Yanomami within the community to make canoes —bongos; the whole process seemed very powerful, fascinating and important. A bongo where almost the whole community can fit in is made with only two simple tools and each person has a crucial role in the construction process, even if they do not necessarily touch the wood directly. I was allured by the way in which they worked with materials they had at hand: if something was needed, it was solved in that very moment with whatever was available. Then I asked if I might be accepted as an apprentice and they responded: if we teach you how to make a canoe, what can you teach us in exchange? This left a profound mark on me, it changed my entire life, and from that moment on I understood that the exchange of knowledge is an extremely generous position to take up in this life, where everyone has something we can learn and something we can teach in exchange. And this became a key part of my life and my practice: understanding education as an exchanging process.

In the 90s, your work proposed a criticism of the violent mechanisms imposed through the idea of progress in our colonial modernity, as well as neocolonial forms of oppression. What was your goal in rethinking these “official” narratives, with their “absolute truths?” How did you become interested in the process of unlearning these epistemologies?

Well, having been born and raised in Mexico during the 60s-70s, the conversation between us young people was precisely about who is the owner of history and what are the absolute truths. We were questioning the official narrative and that is part of Mexican history in general. I arrived in Venezuela with that in mind, but now we’re talking about an extremely important date, in which we’re getting to see the impact of the Spanish invasion on the continent. I’d read about certain indigenous communities that had people that were not from the community but rather anthropologists and yet nonetheless I couldn't find those copies in any of the books belonging to the communities. The people in those communities knew how to read and write, but the missionary schools hadn’t taught them to be authors of their own history. It worked in such a way that the people from the outside would come in, coexist with the community and write their history from their perspective, continuing a narrative that was extractivist of goods, values and cultural wealth.

So when I’m asked what could I teach them in exchange, I propose that the community writes their own history, in their own words, so that they can collectively decide which topics they want to narrate and have all of that information set into a printed book, made of handmade paper with local fibers, thus redesigning technologies that they’d already been using to solve problems and necessities.

Laura Anderson Barbata: "Archivo X" (1998/2023). Handmade abaca paper bundles with inserts from the New Testament in Spanish, Ye'kuana, Yanomami, Ashuar, Mayan and Quechua on a bamboo structure, unique installation of variable dimensions.

Photo: Olympia Shannon. Courtesy: Laura Anderson Barbata.

Laura Anderson Barbata: "Caracas vemos (corazones no sabemos)" (1997). Wooden hand, engraved pearl and wax.

Courtesy: Laura Anderson Barbata.

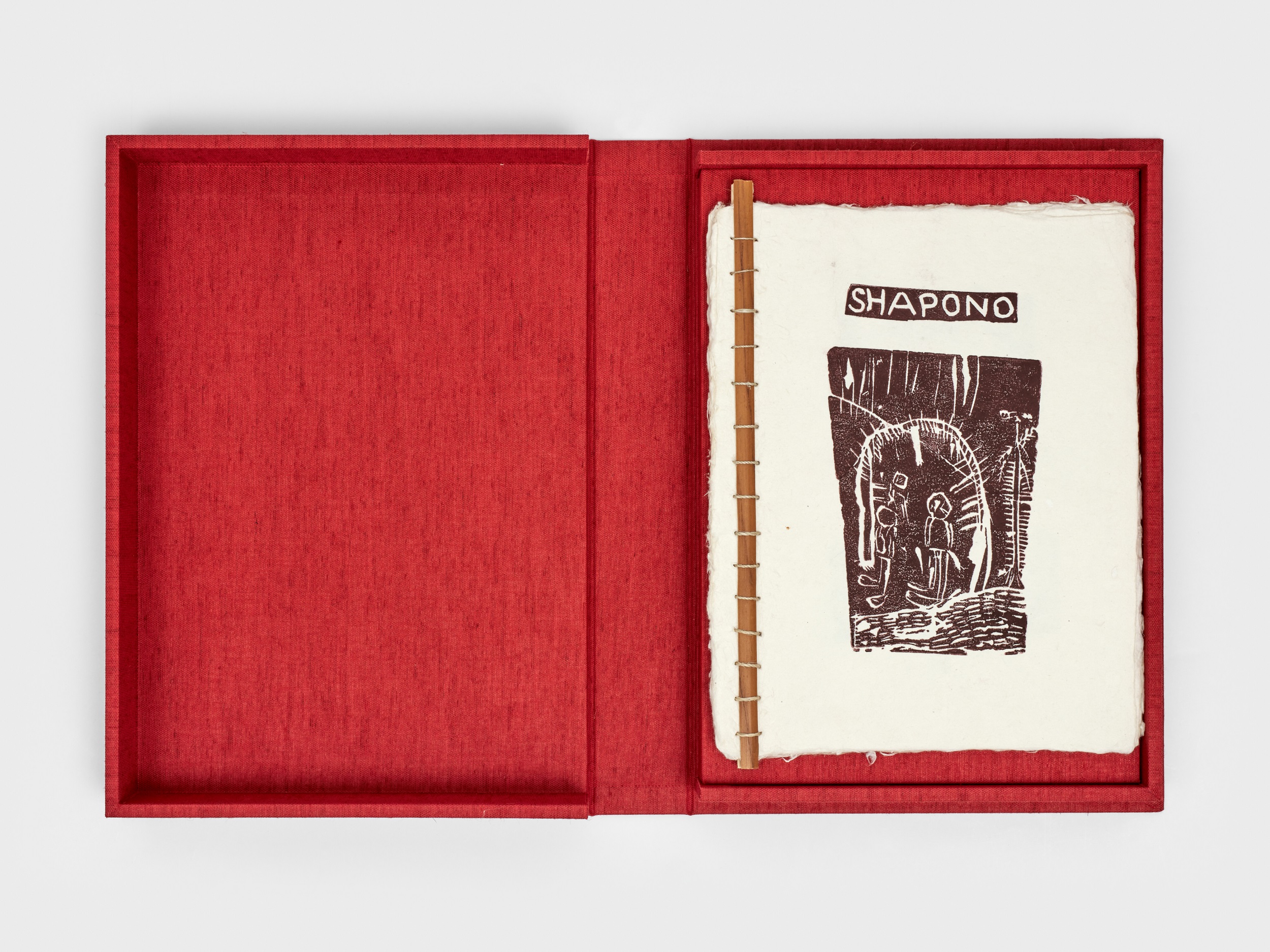

They liked the idea and said: our first book will be Shabono, the story of how the first shabono was built in our community. They learnt to build the first house from Omawë and Yoawë, two brothers that were both gods, and they still do things the same way, transmitting a history that has been narrated orally. So the members of the community that already knew how to read and write went to the shaman, asking him to narrate the story again, and they took notes thinking that they would have to summarize it in such a way that it could be contained into a book. This was an important exercise for me, in which I could involve the shaman and all the oral history into new possible forms determined by the community to tell their own story.

I think it’s important to mention that Shabono, nowadays, can be found in libraries outside of Venezuela as well, which means that their history has reached new readers and new audiences that are learning from it.

Yes, this book was a crucial moment for the community because the first copy received the prize for Best Book of the Year from the National Book Center in Venezuela. From then on, we felt the need to do something more. I sought consultation—I’ve always been advised by experts on paper and books—and was recommended to do a 50-copy edition, numbered and signed by Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe. And so today, copies can be found in renowned collections and libraries, even in some public universities.

In those instances where learning happens through exchange, how do you take into account the historical dynamics of power that have created a world full of inequality?

Your question is complex. I think it is important to understand, when seeking to get closer to traditional knowledge, what we bring in in regards to our attitude and our cultural baggage. In my opinion, it is fundamental to build horizontal platforms that promote and recognize the knowledge that is necessary to stop the replication of these dynamics of inequality. And to have these platforms become collective exercises of exchange in order to truly reach a level of self-questioning within that horizontality; it is absolutely necessary to do this in conversation with the people you are working with, in order to know what they think, how we’re doing, how the dynamic is progressing, how our work is being carried out, if they agree, if we need to redefine the functions or the objectives, if we’re doing anything wrong.

Yanomami Owë Mamotima, paper and books manufacturing project and the Yanomami Intercultural Bilingual School: "Shapono" (1999-2001).

Courtesy: Laura Anderson Barbata.

That is to say, there is authenticity and honesty in our will, these are exercises that must be carried out continuously, in my opinion, because not only are we in danger of replicating an inequality that implies a vertical hierarchy, but also of creating dependencies—and a fundamental part of my job is not creating dependencies.

For example, regarding materials, working with what is at hand is our way of dialoguing with our body and our environment; it speaks about how we move in this world. Respect and dignity, I think it’s important that we learn this and that we put it into practice in the community. We can’t learn and exercise it in the solitude of a studio or in a classroom, since it is something that must be practiced in the world because it relates to the knowledge of the body.

Between 2010 and 2015 you were a professor at La Esmeralda, one of Mexico’s most renowned schools. How did you translate your artistic perspective, which emphasized exchange, into a context of institutional teaching?

It was an honor for me to be invited to teach at La Esmeralda. They wanted me to speak precisely about these kinds of works that are community projects, social art, whatever you want to call it, and it was a production workshop. I had already been giving workshops in other places, such as Yucatan, in La Escuela de Arte, where I was experimenting with the notion of creating communities within pedagogic spaces as a form of activating other ways of relating to your work. In these workshops, it was also important to practice horizontality and not dependency, because oftentimes in school we want to be told what the formula is, how to reach somewhere specific.

So I receive the invitation, and when we’re trying to figure out where the workshop will take place, which physical space in the institution they can assign me, I begin to note some resistance from other professors, and I immediately understand that there is a symptomatic situation, as I am running into colleagues who see too many problems in me generating a workshop before or after their class. And so I understand that for my workshop to be a success, for it to operate well, it must be outside the school, while still being a part of it; therefore I create a program called “Remora.” A “remora” is the small fish that feeds off the shark and lives in a symbiotic relationship with it.

I assume the role of the remora and find a provisional structure, a tank made of tin, that was stuck to the school, and I ask Eloy Tarciso, the school’s director, to let me use that place as our classroom, presenting him the philosophy and the idea behind the remora. He accepts and for me it became crystal clear that to carry out projects in public spaces we need to be outside of those structures; however, these institutions also need our workshops because these kinds of actions and ways of creating also feed the shark with new perspectives. The principles behind “Remora” are collaboration, sharing, horizontality, reciprocity, the act of not creating dependencies, the constant questioning of the artist in their path to dissolving authorships.

This experience of learning from outside the school, of walking, od experimenting other situations, of knowing with the body, is completely different from from being sitted in a chair in a clasroom. And that change, which is perhaps not notable at first, has the power to change it all.

I completely agree. I feel like it was important to break these structures, these expectations that the student body had in relation to how they move in a space called “school.” There is an automatic element, a channel that one does not perceive so much because you already expect it; you’re moving through a channel of expectations that generate a sense of security, since they’ve worked for hundreds of years for certain things. But when you modify the way in which you occupy space, how you move in that space, a wide array of possibilities opens up to you, showing new ways of perceiving not only your body, but your own thoughts and world.

And this can be seen in your artistic practice, for example in that you’re used to walking along the same route every day, and then suddenly one day you bump into the Brooklyn Jumbies, which speak about racial problems, about gender, about the economy, and you find yourself considering that space you occupy every day from a completely different perspective.

Yes, it’s about making that space that you occupy and walk through every day become suddenly interrupted by an action that is completely alien to you, to what you expect. That’s why, speaking from the academia, I was speaking about breaking these structures, these formal expectations, beginning by the body, by how you move and how you occupy space.

Laura, both in Indigo Intervention, begun in 2015, as in your current project, Cochineal Intervention, you are committed to a profound investigation on the little-known history of the links between the circulation and the significance of the color indigo or cochineal, and the violence regarding race and gender. As someone who works closely with textiles and dyes, could you talk about the role that the symbolic value of materiality holds in these projects?

The symbolic value and materiality are very important in the work of carrying out profound research. In the process, one is constantly learning, centering the investigation as part of our own education as artists, which never ends, and this part of historical, theoretical investigation begins to form a fundamental part of the contents and the plastic solutions of the work, of the interventions. If we speak about Indigo, it is a way of reclaiming the symbolic value of this textile, this color, this dye, which is one of the most active, since it is historically associated with royalty, with knowledge, with protection. Even some communities consider textiles dyed with indigo as protective and infused with medicinal properties. So by understanding and recognizing this meaning, we can see how to bring more attention to it. By highlighting, amplifying, and well, literally I’m amplifying it because I’m also working with characters such as the Brooklyn Jumbies or the Zancudos de Zaachila, who dance over stilts. Then it becomes highly important to integrate this symbolism in the work.

As for Chochineal, by studying, for example, the history of extractivism of cochineal, the impact its presence had in the world, in the world of art, in Europe, is not casual, it is not minor, it is huge! But above all, by studying the material in itself, the cochineal in all of its phases —historical, natural—, the process speaks to me of the themes, it helps me focus more clearly. I begun by working on the topic of the cochineal by speaking of the invisibility: the invisibility of people in institutions, in museums, all the people that aren’t seen: the safety guards, the cleaning staff, the secretaries, the curators, the restorers… and studying cochineal has also led me to the invisibility of women. To extract cochineal’s extremely rich color, which may range from blood red to a pale pink, from oranges, to violets, that color is given by a female cochineal. The male does not give color. But to extract the color, the cochineal must die, it must be sacrificed and then ground. When I’m reflecting on these processes, the extraction of the color of the cochineal, I’m already speaking about invisibility and about women, which offers me many ways of getting closer to the topic of gender violence. This is how each work’s layers are formed.

Laura Anderson Barbata: "Intervention: Indigo, Bushwick" (2015). Presented in 2015 in Brooklyn, New York, in collaboration with the Brooklyn Jumbies, Chris Walker, and Jarana Beat.

Photo: Rene Cervantes. Courrtesy: Laura Anderson Barbata / Marlborough Gallery.

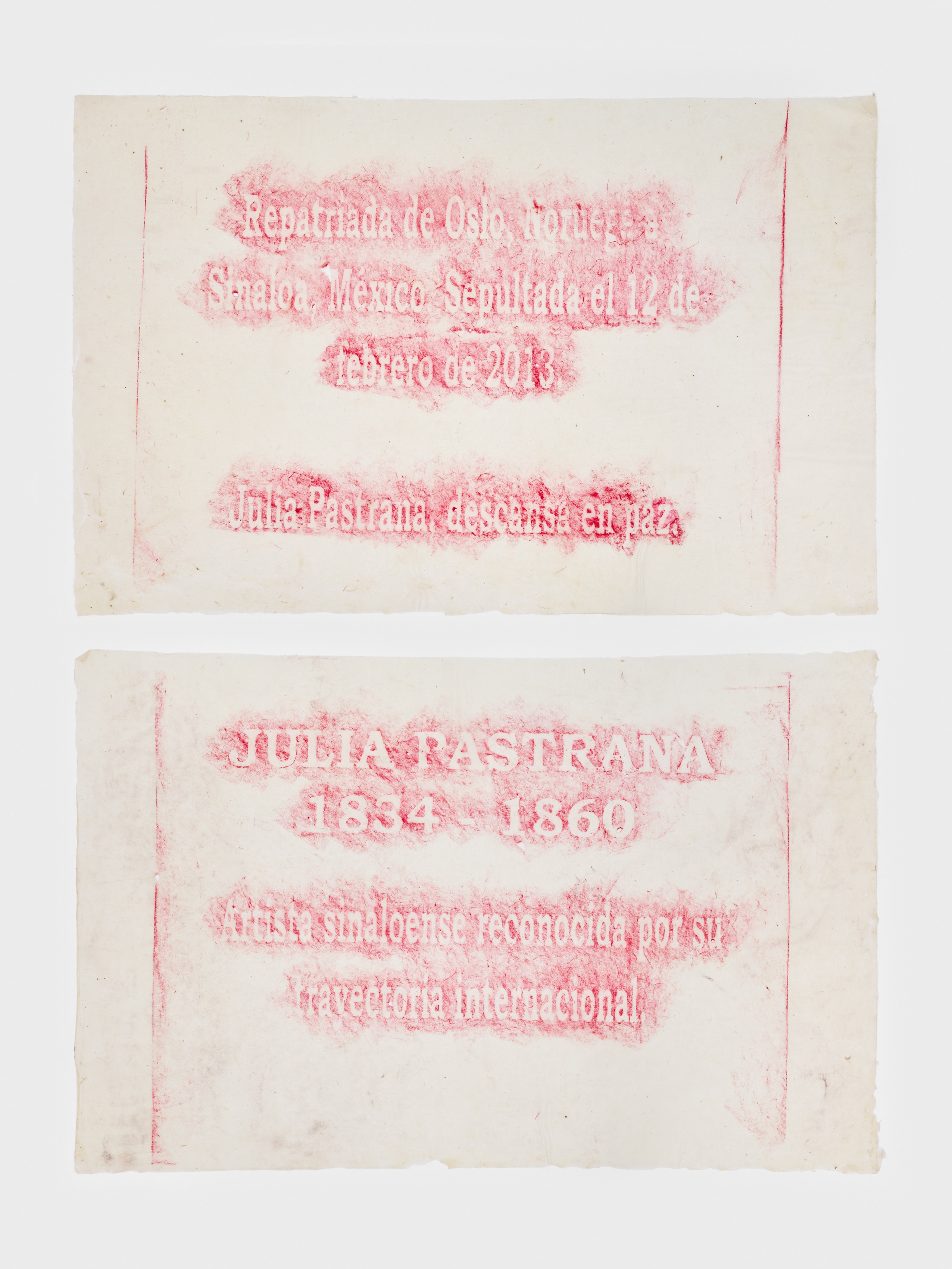

And as you say, it is a way of speaking about the present moment by means of history, and of showing that the same problems are still present in our world, in our culture. It is dangerous to forget that history because we will keep repeating that same violence and I think that this aspect of your work is fundamental, this way in which you show the presence of history in the present moment, especially in your project about the repatration of Julia Pastrana. You dedicated 10 years to collaborating with diverse people from various countries in order to repatriate the body of the nineteenth century opera singer, Julia Pastrana, from a deposit in the University of Norway to her birthplace in Sinaloa, Mexico, whicg you finally achieved in 2013. This is an interesting case that shows us the dark side of education, such as scientific study that tries to analize or study “different” human beings. How do you consider the use of language and scientific study in regards to education?

Your question is full of a thousand stuff and a thousand places where one could jump in from. In the case of Julia Pastrana, it is relevant to mention the abuses that she suffered during her life. Julia Pastrana was an indigenous woman born in Sinaloa de Leyva, in 1834, with a condition called terminal hypertrichosis and gingival hyperplasia; this means that her body and her face were covered with hair and her jaw was very prolonged. These conditions were used to justify her exploitation, not only for her genetic condition, but also for being a woman, indigenous, Mexican. For all of these motives, she was taken in the Victorian era to justify the preocupations that assailed them during that moment, such as: what is the line that dives that human from the non-human?

We’re talking about the historical moment when the theory of evolution was being introduced by Darwin, who himself met Julia Pastrana, but never referred to her as an alien being, but rather as a normal woman with a condition that produced much hair in her face and body, but other than that, there was nothing extraordinary about her. However, the language that was used to commercialize Julia Pastrana drank from scientific waters in its way of analyzing human beings, describing her as the “bear woman”, “monkey woman”, “marvelous hybrid” and “the ugliest woman in the world.” They even convened “scientists”, paid for by Julia Pastrana’s manager, to in some way explain this person and justify the fact that she was in that stage, even though she was an opera singer and ballerina.

The presence of vocabulary, of scientific language in a spectacle of this kind was used to appease the discomfort that assailed the Victorian era: I am or I am not. They were questioning what is civilized and what is not, what is culture and what is “savage”, what is feminine and what is masculine. The very presence of Julia Pastrana challenges all of these expectations, her body dares to occupy that space that defies all of these functions; it cannot be defined under a Victorian optic because she, with her very existence, challenges those notions in front of the audience.

Laura Anderson Barbata: Tracing of Julia Pastrana's tombstone. Charcoal on gampi paper.

Courtesy: Laura Anderson Barbata.

Even today, scientific language still works as part of a discourse that justifies the exploitation of other people, under the guise that it is educational and so we end up seeing desiccated bodies in an exhibition that travels around the world. Scientific language educates you and, as it does, it elevates you, and as it does, it separates you from that which is other, and by doing that, by providing that comfort, it keeps justifying the exploitation.