Jesús Torrivilla: This interview is for a project built around the idea of the ‘school,’ and you mentioned earlier that you hated it. Why?

Learning to Bring Down Walls

05/05/2022

with Mónica Mayer

Jesús Torrivilla talks with Mayer about her experiences with Judy Chicago at the Woman’s Building, about her experiences with teachers such as Juana Gutiérrez and Armando Torres Michúa, and about art as a way of inhabiting the world: a ‘hammer’ for bringing down walls and learning to express her truths.

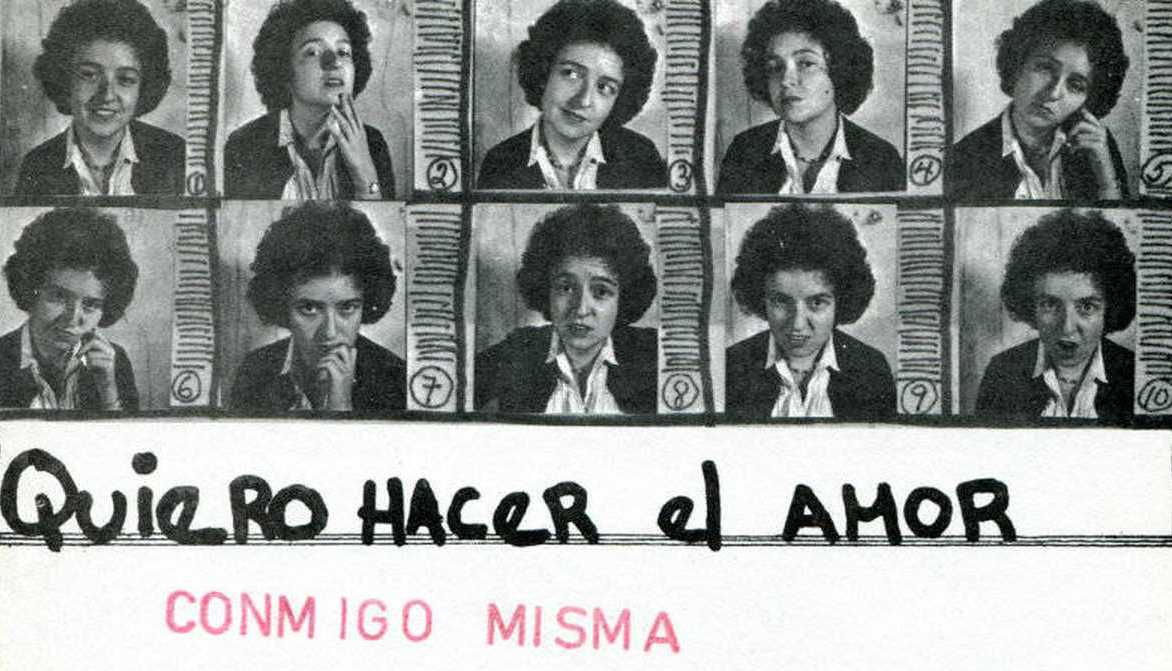

Mónica Mayer (Mexico City, 1954) is a Mexican visual artist and feminist activist, known for her conceptual work and her performances that address the role of women in society. Her work has made her a reference point within the art world of the continent, thanks to a feminist approach calculated to make history since its inception. Among her work, the conceptual project Pinto mi raya is an archive containing more than 40,000 documents, hundreds of conferences, and interventions in public spaces, the media and schools, in which she employs listening and a pedagogy of significant practice.

Mónica Mayer: Indeed, I hated school. They wanted me to learn things by heart that had no relevance whatsoever, neither in my life nor my interests. I was terribly bored. I would spend time with my elementary school classmates devising highly performative projects on how to waste more time in class: “I'm going to drop my pencil and, instead of taking 10 seconds to pick it up, I'll take 20.” We were bored! We did not see the point in education. We learned more about arithmetic and the passing of time from our games than from what was going on in the classroom. I suffered a lot because of the restrictive methods of traditional schools. I was drawn to art because it was the only thing I could go on studying in this life. It was not because I said, "I am an artist" but because it was what I found bearable.

Teaching to think within an educational system based on memory seems like quite a challenge...

It is, indeed, within some methodologies, within certain types of traditional education. You are not supposed to think; the teacher is supposed to tell you the truth, and you learn it, repeat it, and do not question it, you do not go outside of it.

In later years, I was fortunate enough to come across other teaching methods. When I started the university course, I already knew what I liked. I studied at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (ENAP) [National School of Plastic Arts] with teachers such as Juan Acha and Kati Horna, but there was also a strong component of self-taught education. I have read all my life, about many things, like a degenerate — now less so because I no longer see so well. We would go to Café Moneda afterward, and that is where our education took place because we read about many things that were not just what they gave us at school. We went to the movies and to the theater, we enjoyed it a lot as a group.

What can you recover from your experience at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas with teachers such as Juan Acha, Juana Gutiérrez, or Armando Torres Michúa?

I really liked that they challenged us. Juan Acha spent the first semester strolling back and forth in front of us talking about the structuralists, explaining all the theory to us, and we were all clueless, staring with bewildered faces. He on the other hand, expected us to level up to him. Little by little, we went on reading and understanding. He had a Latin American approach, ideas from Non-Objectualisms, ideas about how to do all this work. Acha adapted his language — which taught me a lot about the importance of communication — thinking of publications for different audiences: middle school, high school, university.

The first time I went to the Woman's Building in Los Angeles for a two-week workshop, I came back wanting to talk about feminism and art, even though I was very shy. Then Armando Torres Michúa and Juana Gutiérrez, who taught Art History, said to me, "Give a lecture," and they accompanied me. We sat on top of a desk in the Aula Magna (so that it would be informal and I would not feel like I was giving a lecture). The two of them talked about women in art history, and then I blurted out my speech. It made me feel accompanied. Having a teacher is really about having a company in your process to help you grow. They were wonderful experiences.

You have spoken of accompaniment, of the ethical position between life and art. How would you define a great teacher?

As one who manages to make knowledge meaningful. For it to be meaningful, it must generally relate to what you are living or what you have lived, to your emotions, to your context. Presenting such purposeful knowledge seems fundamental to me.

When you started studying, how was the conversation in Latin America with the so-called Non-Objectualisms?

It was a bit random because there were no books, or there were very few. I remember the first time I read Conceptual Art by Ursula Meyer. I remember reading it and crying because it was changing everything I understood art to be. It was opening up this whole panorama for me. I was crying with anger. There was a book here and there, we were beginning to see. But how do you get out of what you have been traditionally taught to begin raising other kinds of questions that we had not necessarily done in school?

On the other hand, there was Juan Acha, who was organizing the Primer Coloquio Latinoamericano de Arte No-Objetual [First Latin American Conference on Non-Objectual Art] in Medellin (Colombia) at that time. The issue of Latin America was fundamental; it was the height of the dictatorships and many artists from Argentina, Chile, and other countries had fled to Mexico. There was a great awareness of what Latin America was, of the serious political issues between the North and the South. We worked with that premise, with that awareness all the time.

In terms of feminism as a discourse and practice in your work, was it at that point of the discussion that it began to be important to you?

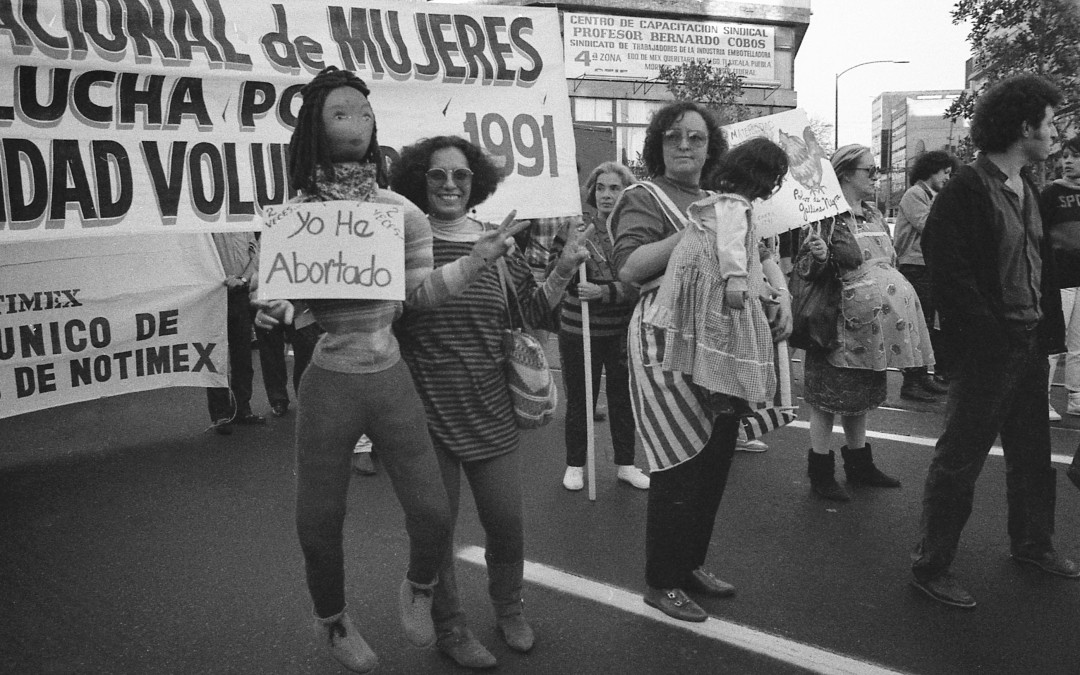

It began there, although we had been doing exhibitions for several years. There was a group at the ENAP, in San Carlos: there was Magaly Lara, Jesusa Rodríguez, Rowena Morales, Karla Paniagua. We asked questions, had questioning ideas, organized women's exhibitions, feminist exhibitions.

Several of us were integrated into the feminist movement, but there was a huge gap with the leftist movements because the left considered that class struggles had to be resolved first and then everything else would come naturally. Feminism and the lesbian-gay movement did not agree with that and proposed that there were other ways of doing politics. They were only beginning to mix: some artists were in the Taller de Gráfica Popular [People’s Print Workshop], the critic Raquel Tibol participated in political organizations. But it still did not feel like something that was part of "real" history. If you study the seventies, it is only now that they are integrating women artists, but the historiographical narrative was always about the groups Proceso Pentágono, Germinal, Suma. Neither feminism nor women artists were included. That has begun to change in the last decade.

What was your perspective on how long the feminist struggle would last?

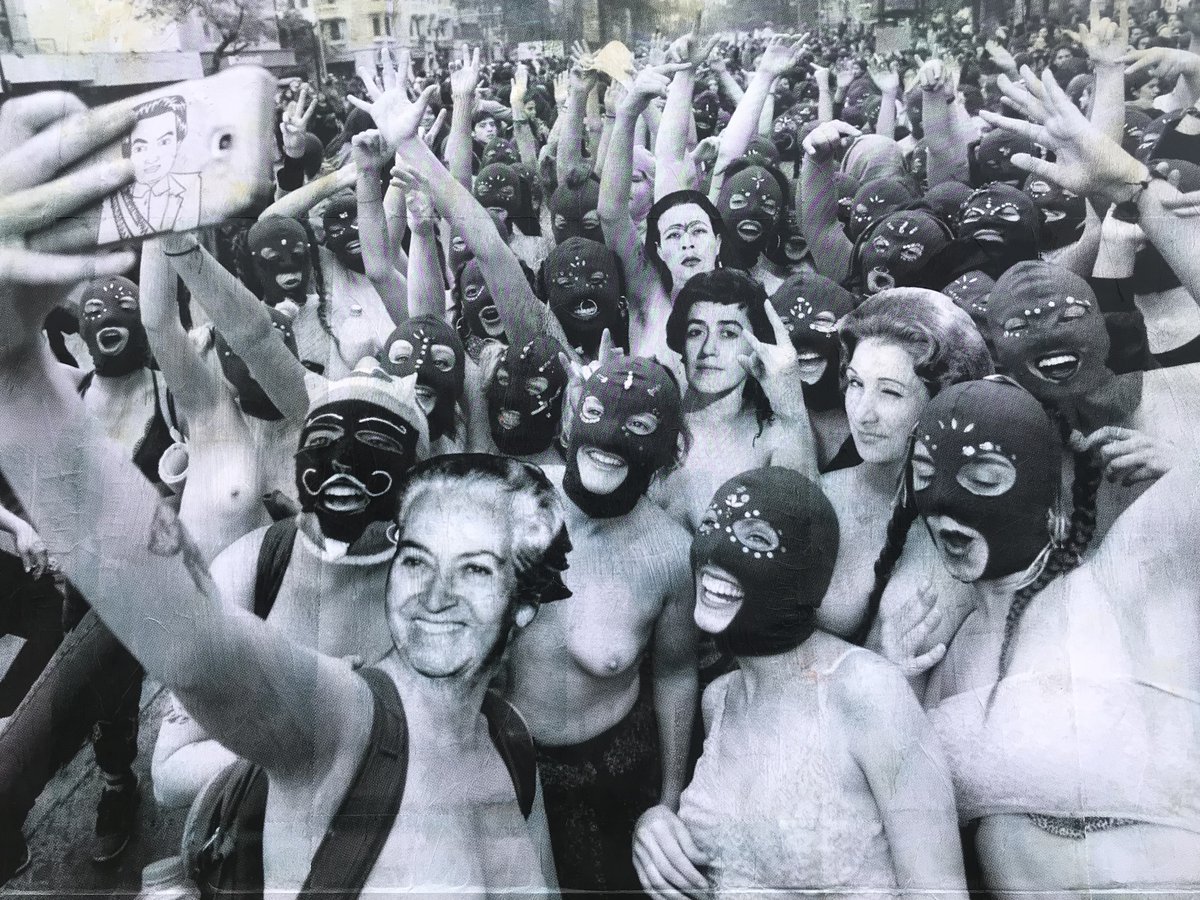

I believed that the patriarchy was going to fall in about three years; that is what I gave it to collapse. The reality is that it is not going to end quickly. It took us many decades to build the patriarchy, to make that system and implement it. It is embedded in our marrow: we move according to what the patriarchy tells us. We think and feel according to what it calls for in different contexts. Cracking this requires some profound processes of education and self-reflection, and those take a long time. You can even change the laws, but if there is no change in culture, if education does not change, if we do not change from within, nothing will change. So, it seems to me that this is something that will take a long time.

What educational methods did you encounter at the Woman's Building?

When I went to the Woman's Building, I had already read Paulo Freire, Piaget, Montessori, and The Little Red Book of School. I used to read a lot about education and was very interested in it, but that was the first time I actually experienced an “alternative” or experimental method because they were devising it, they were inventing from experience.

There was the 'Small Group' method, a basic in the feminist movement, which as far as I could find out, came from China, when they brought together peasants and workers to talk about their problems. Then the revolution got started! Some indigenous communities in Mexico use it too: the whole community sits down, of all ages, and they talk.

The Small Group is one of the main tools of the feminist movement, I always encourage it, and I think it is fundamental. It consists of giving each person the same space to speak, and if you cannot talk, you learn. Each one speaks from her own experience, without judgments; in the end, you see the similarities and differences, understand how the system works, not only in the personal life but also in the political life. You begin to really see the patriarchy and where all its cobwebs are.

How did you adapt to such methodologies?

The first year was awful for me because I used to think to myself, "These wretched women! When are they going to talk about politics for real!?” It was hard for me. Until one day, after a whole year, I understood its power, the importance of how solid and different it is — in both artistic and political processes — to understand your experience, where you are at the moment. To situate yourself! To know who you are and why you are saying that, what it is that commits you to that struggle, and what you find difficult within that struggle.

I always say that my fiercest battle in feminism is against patriarchal cobwebs. The first stage of the struggle is learning what we need, what bothers us or refrains us from changing it, and then demanding what we want. I see it the same way at schools or in public transport: the moment most of us women put a stop to being groped on the bus and those around us do something to prevent it, that day harassment will end.

How does the archive relate to a feminist perspective?

At the Woman's Building, there was special care in thinking and developing the archive, making our history. The archive was the only locked place there. There were exhibitions such as one called The Great American Lesbian Art Show, which was quite a novel theme at the time. Upon the show's closing, they took slides and photographs of all the works and handed them out to as many libraries as we could, because we worried about being easily erased.

Feminism, in history and in art, is like a three-dimensional tic-tac-toe (this game where you make crosses and circles). We must change the past narratives from which we have been excluded. We have to act in the present and we have to leave enough materials for the future so that we are not erased again. We must work in these three temporalities. I understood that there, by going and leaving that material in libraries, so that history would not be lost.

I find it very important that education begins with those who are participating in it, creating their own stories, understanding their relevance, and sharing them. That is something fundamental in the way I organize exhibitions and teach workshops: your story is as important as mine. I always say that it is no longer a time to "divide and conquer" but to "repeat and conquer." You go on and repeat and repeat the story over and over again.

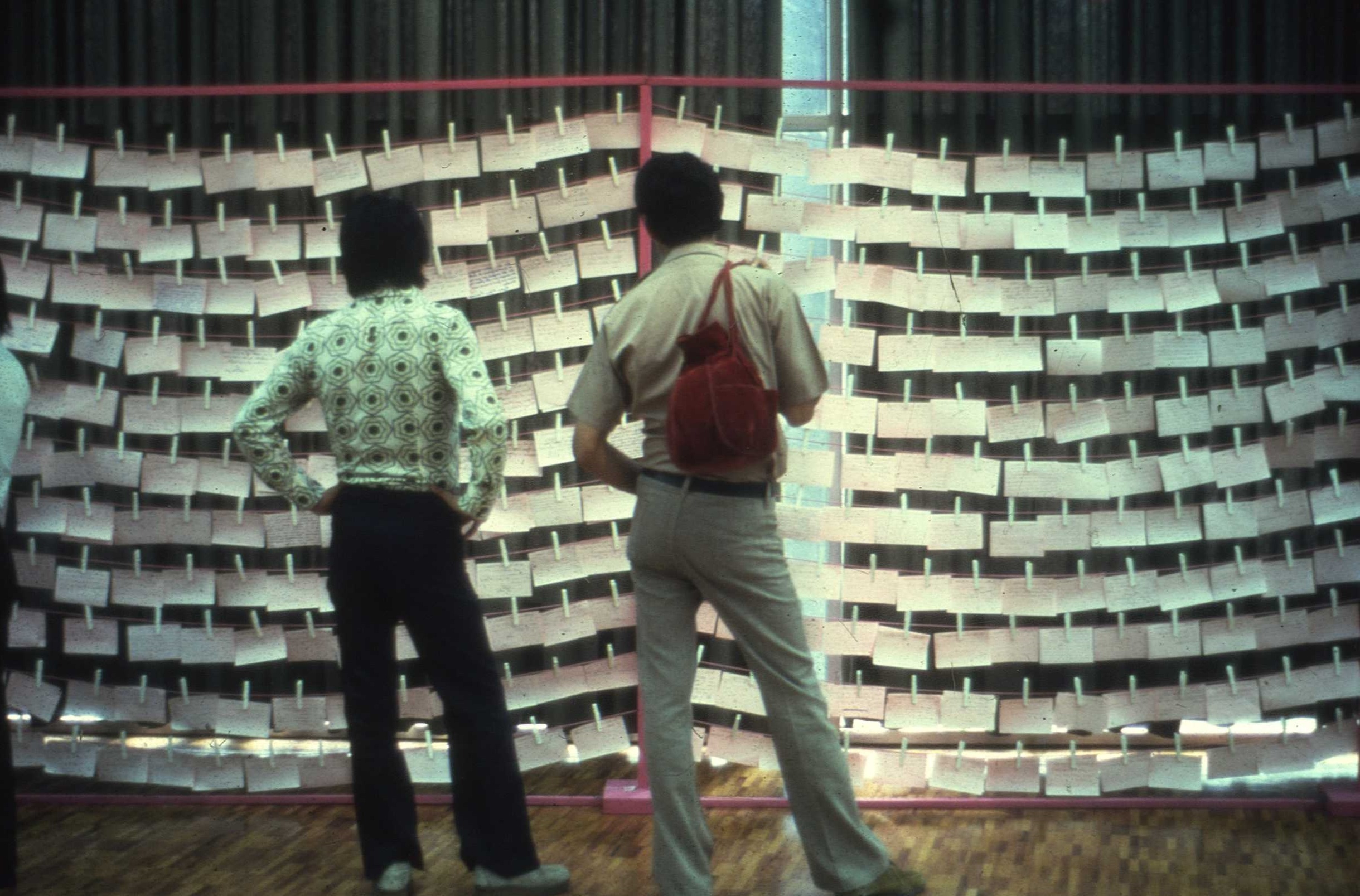

You started your work El Tendedero [The Clothesline] as an idea for receiving denunciations from women in the public space. It has been taken up by younger feminisms, it has gained new relevance in Mexico with the MeToo movement, and it has also become for women a way to tell their own stories. Could you tell us about the growth of this work?

El Tendedero has the same structure as the Small Group: everyone has the same space to talk about a topic from her experience; then, a narrative unfolds. Unlike the current tendederos (which do have influence from the MeToo movement, from the direct action of other kinds of politics, and from the staged noisy protests known as the Argentine escrache), we did not denounce people directly because it did not even occur to us. Awareness was barely being raised. The question asked in the first Tendedero was: "As a woman, what I hate most in the city is..." We were not talking about harassment. Many times, it was just about planting a seed. If someone said to me, "pollution, traffic," I would tell them: "Does it not bother you when they grab your behind on the bus?" Write that. It is not a sociological survey, it is a symbolic artistic work, it can be oriented.

El Tendedero makes us feel accompanied, allows us to see that we are not alone. If you were groped in the street by some guy when you were 8 years old — as it happened to me — it turns out that it is quite a common experience. If you were ashamed and never said anything, the others were ashamed too. Why should we be ashamed of having been groped by some asshole in the street? This process of reflection continues to take place and continues to function as a structure.

And it is a work built from a pedagogical point of view, from your workshops...

The workshop part is fundamental because, many times, we make a workshop and the work comes out from it. Many times, as with the tendederos, the response unfolds and there is space to work on the clothesline and to develop other works as well. I am not interested in just getting help for making a tendedero and that is it. I am also interested in presenting the work, in them making an archive, having all this happen. For me, art, activism, and feminism are not apart.