The time has come for women's awakening!

We want to own our bodies and our lives.

We demand free and unrestricted abortion.

Free abortion so that we don’t die.

We are not commodities.

Neither a decorative object nor a suffering, self-sacrificing mother.

Let’s destroy the macho society that denigrates women by inciting them to compete.

Miss Revolution. A new concept of beauty.

Domestic work time IS time and IS work.

In both developed and underdeveloped countries, machismo reigns equally.

For the right to a home of one's own.

Toward a combative, national and popular feminism.

Woman, don't you hear the hum of the future?

Don't You Hear the Hum of the Future? A Throbbing Archive for Unlearning

03/16/2024

The AAVJ not only articulates Ana Victoria Jiménez's militant activity, her interest in photography, publishing and performance, but also documents the broad collaborative networks of activists and visual artists in which she participated [...] —including groups of women who did not call themselves “feminists” or even rejected that category.

Feminism is a form of creative and plural indignation. It is a point of departure for acting not only in regard to a past but toward something that perhaps has yet to be articulated or that still doesn’t exist. Despite the enlightened reason that besieges it, it is a contingent politics, which allows us to question the categories that constitute it and to create languages that allow us to respond to the pain produced by the different forms of power and injustice. It is also a way of reading and learning from this pain, to orient it toward diverse forms of collective political resistance.1 Feminism moves and mobilizes us; it encourages us to take action, to make alliances, to conspire, to listen, and to organize ourselves with others. But this process of politicization and critical awareness of pain is not automatic, it is learned. It depends on acts of translation that allow us to understand how gender norms regulate bodies and spaces, and how gender violence is imbricated2 with other forms of power, including race, class, and sexuality. How does an archive such as Ana Victoria Jiménez’s intervene in these situated processes of (un)learning?

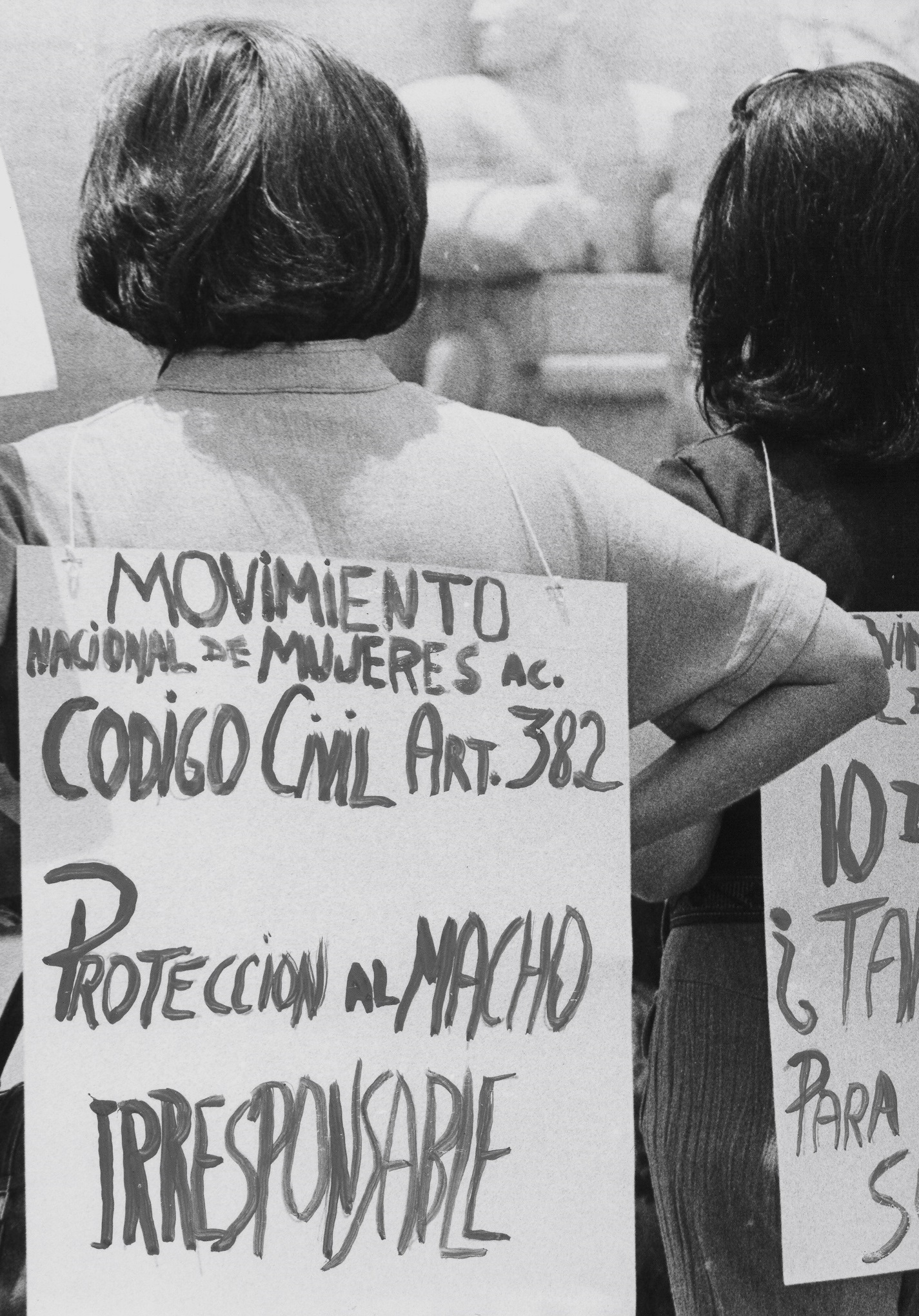

Actions of the National Women's Movement (MNM) at the Mother's Monument in Mexico City, 1976.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

The above phrases can be read on the banners that appear in some of the images in the Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive (AAVJ). Organized in six sections, this collection houses 4,250 documentary records, 250 posters, 300 pamphlets and programs, 100 copies of magazines and newspapers, 3,319 photographs, and 550 books. Ana Victoria Jiménez (Mexico City, 1941) donated her archive in 2011 through the Memora Project,3 adding it to the Historical Collections of the Francisco Xavier Clavigero Library of the Universidad Iberoamericana. The AAVJ not only articulates Ana Victoria Jiménez's militant activity, her interest in photography, publishing and performance, but also documents the broad collaborative networks of activists and visual artists in which she participated between the 1960s and 1990s—including groups of women who did not call themselves “feminists” or even rejected that category.

Ana Victoria says she never intended to create an archive, which invites one to imagine what might have motivated her to assemble this collection. More than a nostalgic impulse, it would seem that it was her own way of embodying her militancy: "a feminism thought and lived in everyday life."4 And the fact is that the gesture of registering and documenting a movement that shakes up imposed ways of life and demands a change in the structures that undermine the possibility of women being effectively instituted as subjects of rights, is a political intervention in itself. These are records that shape alternative visual regimes, questioning gender stereotypes and vindicating women's labor, sexual, and reproductive rights, and, in doing so, they challenge the normative representations of the female body, both in the aesthetic and political spheres.5

March convened by the Unión Nacional de Mujeres Mexicanas, A.C. (UNMMAC) in Tlapa, Guerrero.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

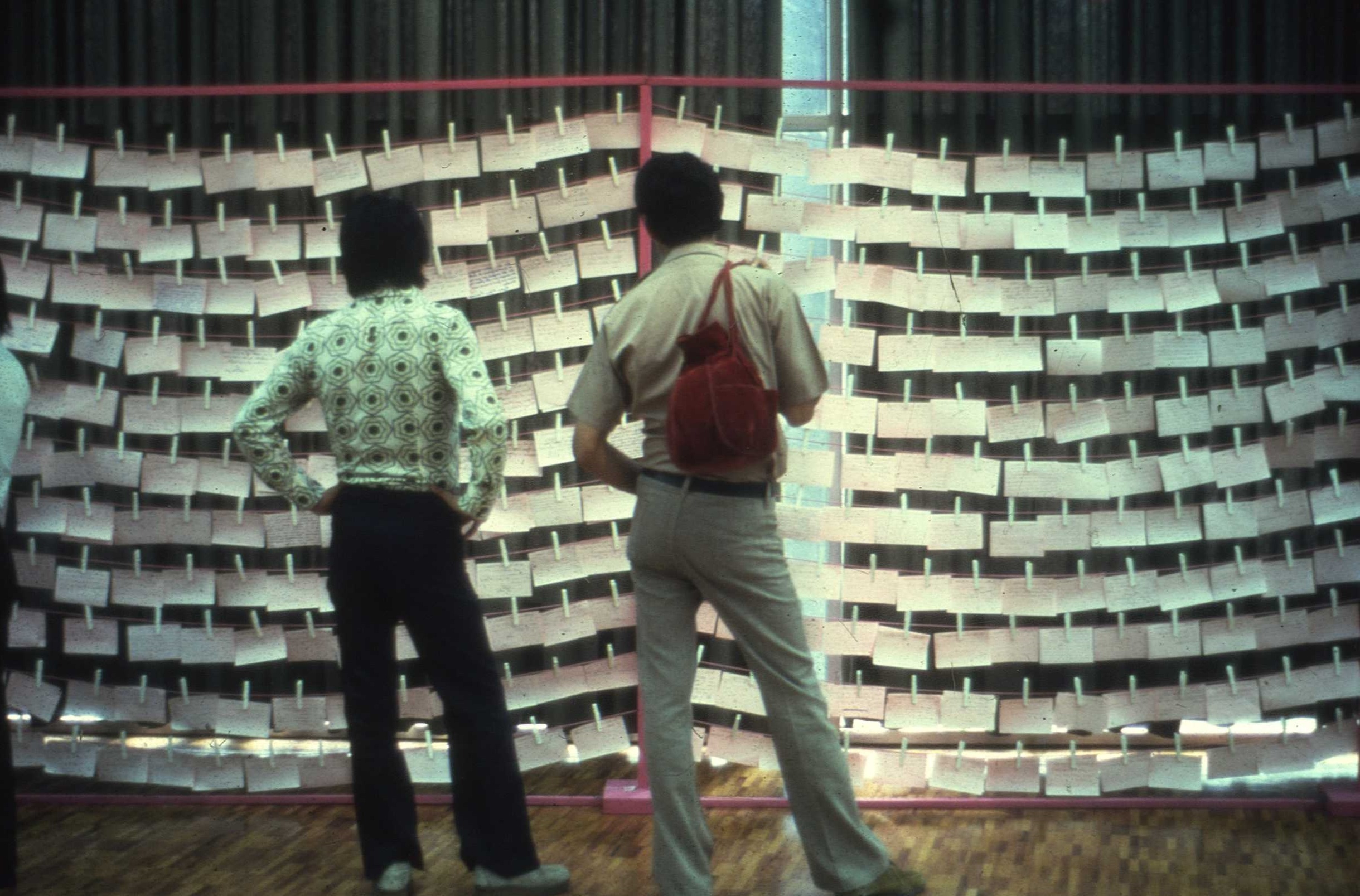

First Women's Congress, 1967.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Demonstration in front of the Chamber of Deputies to demand the decriminalization and legalization of abortion, 1979.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

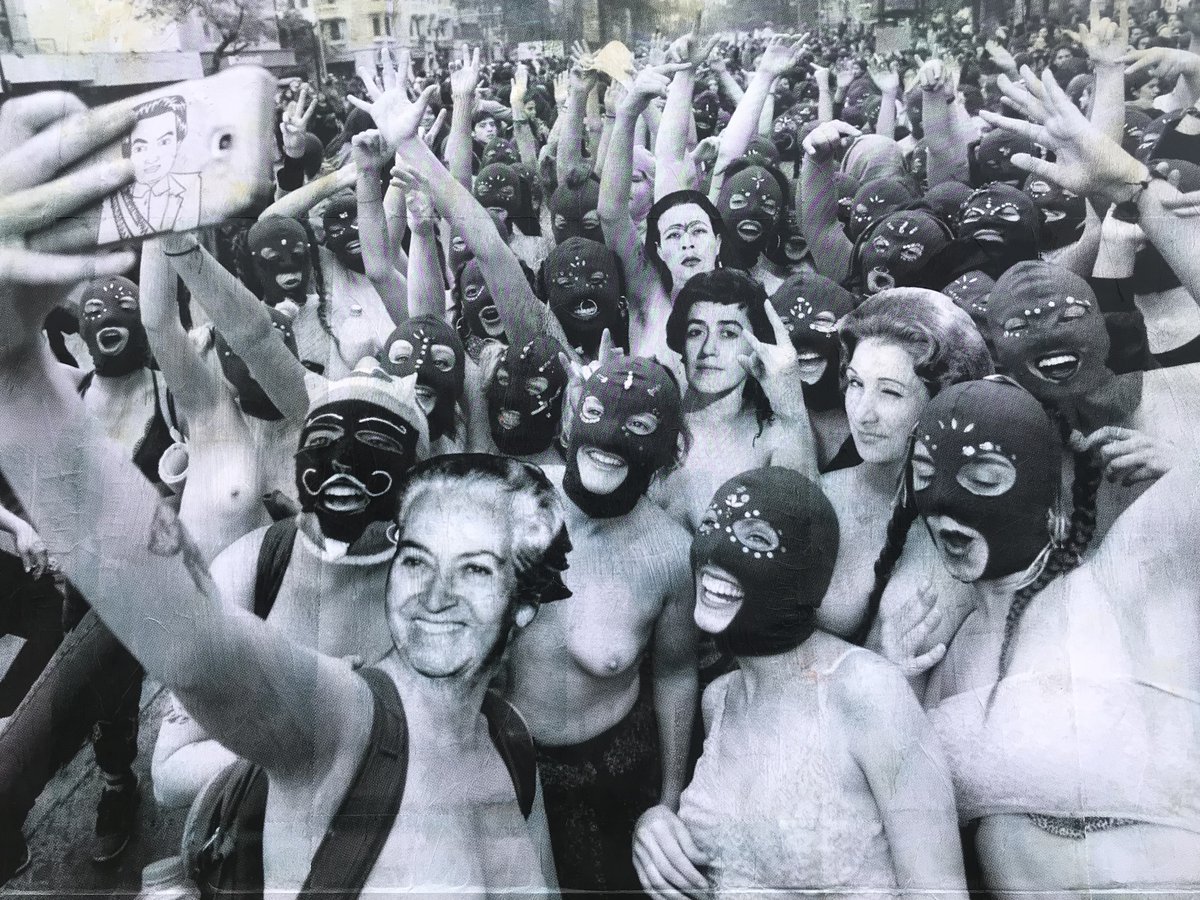

Demonstration to demand the decriminalization and legalization of abortion 1991.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Surroundings of memory and political struggle

After joining the Communist Youth League of Mexico City, Ana Victoria Jiménez participated in the creation of the Unión Nacional de Mujeres Mexicanas (UNMM).6 During the 1970s, she collaborated in various feminist collectives and organizations, such as Mujeres en Acción Solidaria (MAS),7 the Movimiento Nacional de Mujeres (MNM),8 the Coalición de Mujeres Feministas (CMF),9 and the Frente Nacional por La Liberación y Los Derechos de Las Mujeres (FNLIDM).10

As a member of these organizations, Ana Victoria documented various events and actions, among them, were the mobilizations called by MAS on the occasions of Mother's Day (1971) and Father's Day (1972) celebrations. The purpose of these actions was to denounce the inequity of gender roles in family structures, the manipulation of the media, and the objectification of women.

Along the same lines, as part of the activities of the Miss Mexico pageant (1978), she documented the protest in front of the National Auditorium organized by the CMF against the beauty canons imposed by the patriarchal capitalist system. There are also photographs of the event organized by the MNM on the occasion of Mother's Day (1976), in which they denounced the privileges enjoyed by men in the Federal Civil Code, specifically in article 382, which deals with the acknowledgement of paternity outside marriage.11 On the subject of abortion, there are images denouncing the death of thousands of women due to poorly performed abortions, while demanding free access to this procedure and its decriminalization.12

The documentary records in this archive are not limited to the initiatives in which Ana Victoria actively participated. In fact, whoever consults it can notice the wide range of women's groups it comprises: unionized groups, grassroots, urban and indigenous movements, as well as sexual dissidence. The diversity of this collection speaks of the plurality of struggles that, from different ideological perspectives and positions regarding feminism, touch on and weave together painful experiences, which gave way to broad coalitions aimed at transforming the structures that undermine the recognition of women's humanity.

Contingent of the Frente Nacional por la Liberación y los Derechos de las Mujeres on the occasion of the Mother's Day mobilization, May 10, 1979.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Demonstration on the forecourt of the National Auditorium in Mexico City, on the occasion of the Miss Mexico beauty pageant, 1978.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Demonstration on the forecourt of the National Auditorium in Mexico City, on the occasion of the Miss Mexico beauty pageant, 1978.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Demonstration on the forecourt of the National Auditorium in Mexico City, on the occasion of the Miss Mexico beauty pageant, 1978.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Plots and Overlaps

In parallel to her militancy, Ana Victoria was involved with creatives and groups such as the collectives Cine-Mujer13 (1975-81) and Tlacuilas y Retrateras (1983-85). With the former, she collaborated as a still photographer and researcher on two films directed by Rosa Martha Fernández: the Ariel-winning Cosas de mujeres (1975-78) and Rompiendo el silencio (1979). In these films, the female body appears vulnerable, exposed, grotesque, but also politically active. Through documentary and fictional film strategies, these films function as records of a potential archive of feminist demands, women's living conditions, and alternative ways of representing them.14

Contingent of the Okiabeth collective, an organization of socialist lesbians, on the Pride March in Mexico City, 1991.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Protest of the Network against Violence at the Zócalo in Mexico City, 1991.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Protest of the Network against Violence at the Zócalo in Mexico City, 1991.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

The collaboration with the Cine-Mujer collective and her growing involvement in the artistic community prompted Jiménez's interest in photography to take on a more poetic tone after 1978. For example, Cuaderno de tareas (1978-81) is a planner notebook that Ana Victoria created as part of her collaboration with Atabal, a collective devoted to the struggle for the rights of domestic workers. During the same period, she participated in Traducciones: Un diálogo internacional de mujeres artistas [Translations: An International Dialogue of Women Artists] (1979).15 She also co-organized the performance International Dinner Party (1979) by Suzanne Lacy and Linda Pruess, as an homage to Adelina Zendejas, Amalia Castillo Ledón, Elvira Trueba, and Concha Michel, who were outstanding referents—according to Jiménez—in Mexico’s feminist movement.16

In 1984, Ana Victoria Jiménez, Consuelo Almeida, Karen Cordero, Lorena Loaiza, Patricia Torres, and Elizabeth Valenzuela created the collective Tlacuilas y Retrateras. This feminist group set out to analyze the working conditions of Mexican artists and to promote art as a tool for political awareness.17 In the controversial performance La fiesta de quince años [The Quinceañera Party] (1984), which took place at the San Carlos School, the collective sought to reflect on this popular celebration that usually marks the transition from childhood to adulthood for women. In addition to participating in the organization of the party, Jiménez presented El juego de la sirena. Tratando de romper el círculo sin fin [The Mermaid's Game. Trying to Break the Endless Cycle] (1984).18 This was a board game that showed the "fate" of women in Mexican society as a path inevitably marked by reactionary traditions, feminine archetypes, and violent relationships. However, through rhetorical figures such as satire and irony, this piece opens up a space to imagine rituals, celebrations, and affective bonds that could draw alternative paths for women.

Archival Pedagogies

The AAVJ embraces various facets of the women's movement, even those that posed internal disagreements, which still mark the different positions within feminisms today. The pedagogy of this archive reveals that, although feminism wasn’t the main axis of political action for some women's groups, there was still a will and urgency to articulate and weave alliances. For example, there are records of groups that were in favor of abortion, lesbianism and sex work, and also of those that were against; or those that saw legal action as a feasible way to combat the exploitation and violence suffered by women, and those that did not; those who maintained a separatist position in relation to the participation of men in the feminist struggle, and those who proposed the need to create bridges with them; or even those who saw art as a tool for social transformation, and those who saw it as a bourgeois apparatus, disconnected from the struggles of the working class.

Some concrete examples of this in the archive include the records of the activities of the Unión Nacional de Mujeres, channeled into the struggle of working-class women; or the speech of Domitila Barrios during the International Women's Conference (1971), in which she voiced the violence suffered by miners’ wives in Bolivia—an issue that wasn’t in the agenda of the conference held in Mexico City and whose attendees were mainly middle-class, white or mestizo women. Decolonial feminism has shown how this strand of feminism (white and Euro-centered) has systematically suppressed and marginalized the experiences, demands and claims of racialized peoples, migrants, and women living in poverty.19

This entanglement of initiatives sheds light and adds complexity to the histories of the feminist movement in Mexico City. It challenges hegemonic feminist narratives about the equal oppressions among women and counteracts the cognitive penumbra from which feminism is conceived of as a unified bloc. By observing the history, motivations, and strategies of these groups, rather than a uniform bloc of struggle, the archive reveals multiple collective plots with diverse initiatives of organization and resistance, as well as different ways of naming and positioning themselves in the face of what they were fighting against. This lack of a common or "universal" object of indignation, rather than a failure, is an indication of the capacity and scope of feminist activism to move or become a movement.20 That is to say, it speaks of the power of heterogeneous action, which allows it to inscribe its claims in the flow of action, weaving collective plots from difference.

The AAVJ archive is an infrastructure of memory, and as such, it has the power to radicalize our relationship with the past and transform what lives and breathes in the present. In an inescapable conversation with the present, it reminds us that, although indignation and rage are valid, we must continue to insist through existing repertoires of political struggle and also others that are yet-to-come.

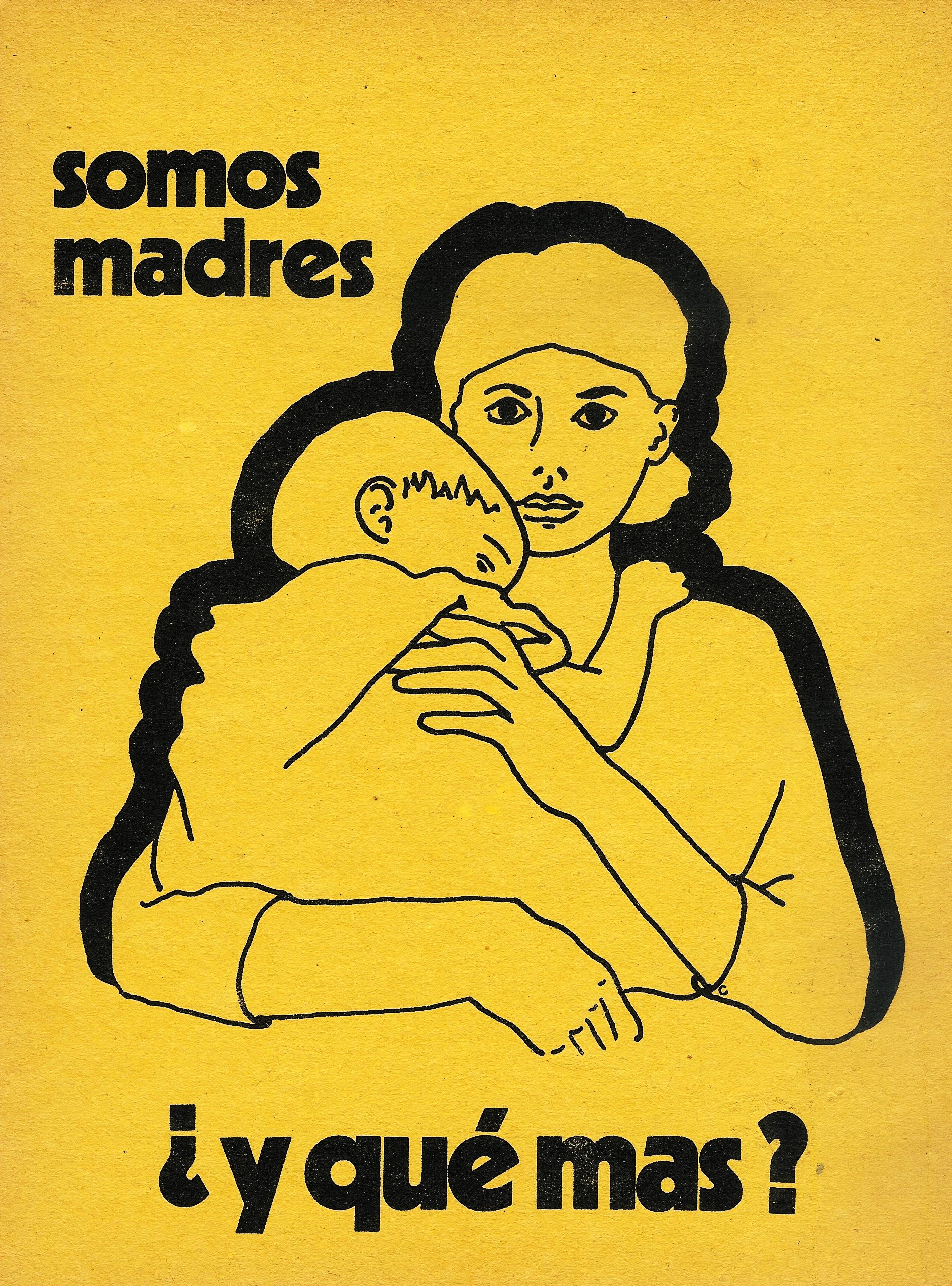

"We are mothers, and what else?" poster, 1971.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Poster by the Movimiento de Liberación de la Mujer (MLM) demanding the liberation of female political prisoners in Mexico and Spain, 1975.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Poster convening a mobilization at the Zócalo in Mexico City on March 9, on the occasion of International Women's Day.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Poster by Okiabeth collective.

Ana Victoria Jiménez Archive. Courtesy: Ana Victoria Jiménez.

The value of its materials resides in the potential histories they can encompass, as well as in the tenacity with which we approach them to mobilize narratives that fissure or tension the pacts of silence, oblivion, and impunity. For instance, a decolonial reading of this collection would invite us to trace other historical repertoires of women's political organization of the time that may have been dismissed by the so-called discursive authorization regimes of hegemonic feminism, due to them not being encoded in the Eurocentric Western paradigm of protest/resistance.

Each activation, reading, listening, and interpretation of this archive is an act that translates pain and indignation into knowledge.20 It is a possibility to expand our field of vision to read the world, and move from indignation to a different corporeal world. It is an opportunity to pause or hesitate, to learn to see the world as something that doesn’t have to be this way, and to reject what is taken for granted. Affectively opening historicity, rather than suspending it, is perhaps the most evident way in which this archive teaches us to unlearn.