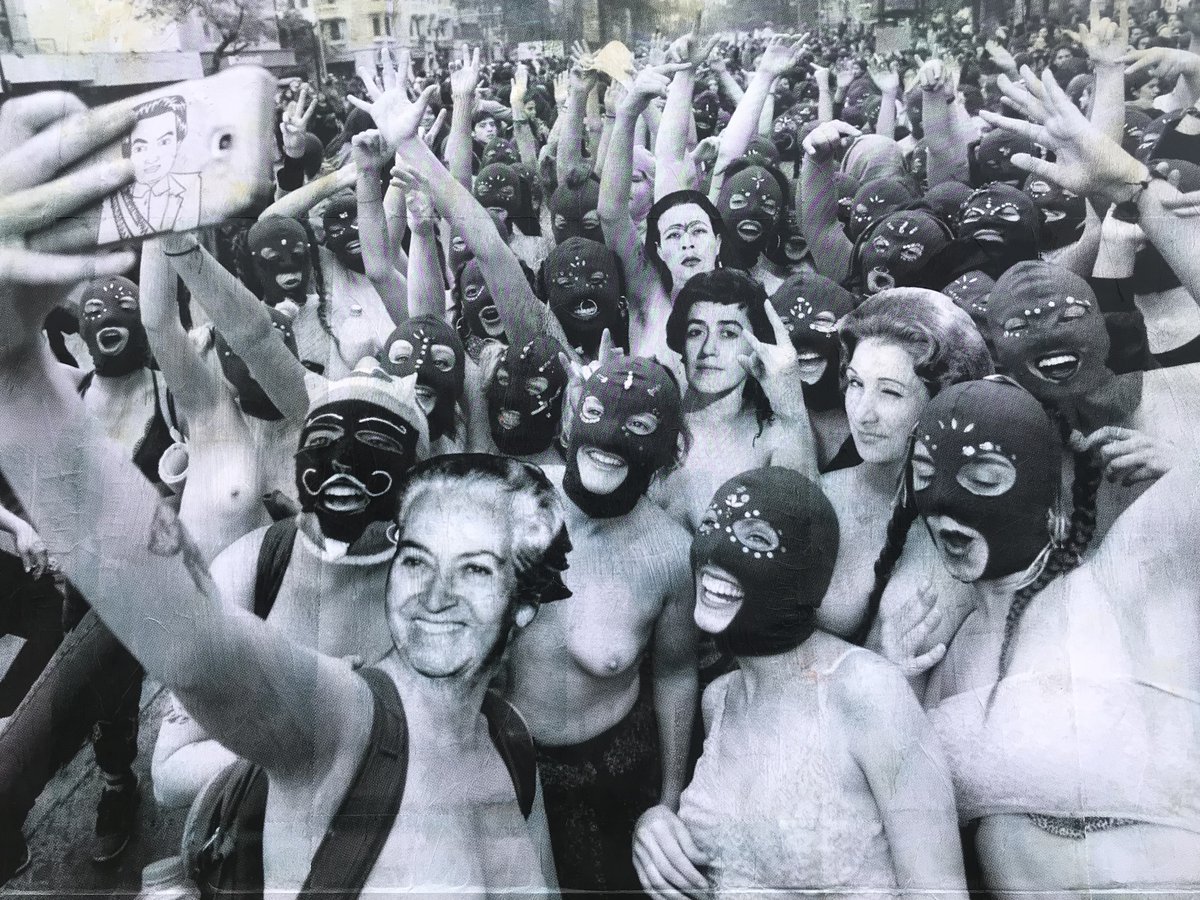

Juana Belén: From “Virile” to “Vile” and the Example We Need in History Books

03/17/2024

Juana Belén was the first female independent thinker and a precursor of the Mexican Revolution. [...] Despite her restless struggle, her name and political activity are never mentioned in mainstream history books. [...] To learn and know about her life and work, we must know how to research through feminist scholars who have rescued her legacy.

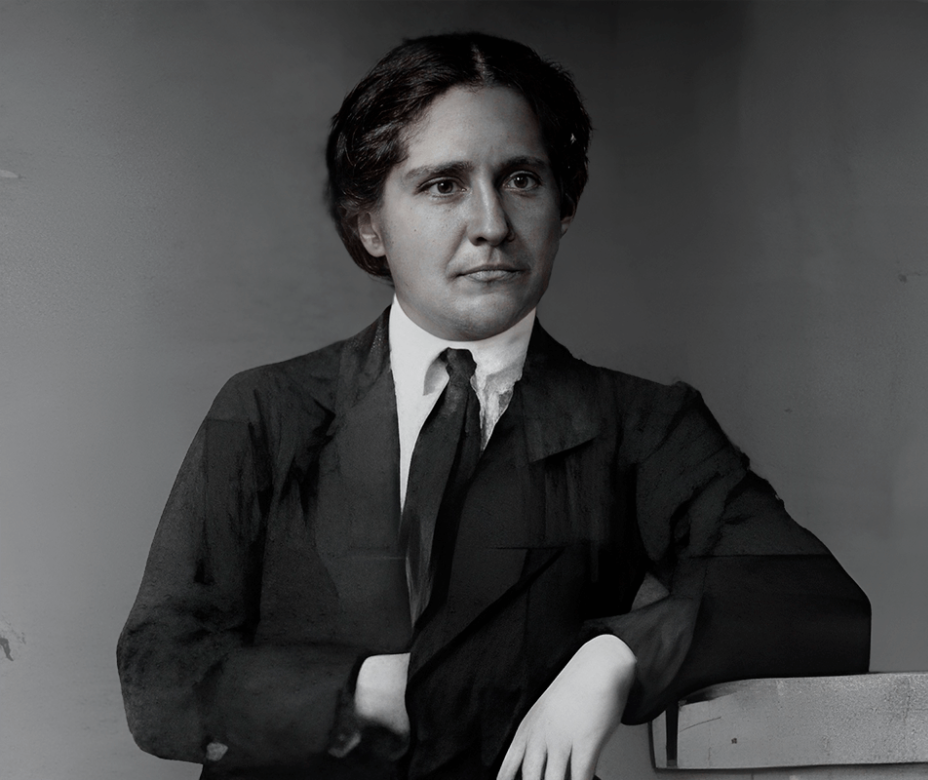

Juana Belén Gutiérrez (1875 – 1942) is one of the most important figures in Mexican history, and at the same time, one of the least known. Juana Belén was brilliant, one most extraordinary woman at the beginning of the twentieth century. She was the first woman to break traditional norms and “formally, openly, criticize Mexico’s social system at the beginning of the century” (Villaneda 1994: 10). Juana Belén was the first female independent thinker (Rubio 2020) and a precursor of the Mexican Revolution. Her struggle lasted a lifetime; she was willing to defend what we understand as social justice, freedom, and autonomy at all costs (Villaneda 1994). Despite her restless struggle, her name and political activity are never mentioned in mainstream history books. We don’t learn about Juana Belén either in elementary or secondary school, nor high school, not even in college. To learn and know about her life and work, we must know how to research through feminist scholars who have rescued her legacy.1

What can we infer about Mexico’s history and education by analyzing the systematic exclusion of female precursors of the Mexican Revolution, such as Juana Belén, Dolores Jiménez, María Dolores Malvaes, or Elisa Acuña, among others?

Juana Belén Gutiérrez, 1914.

In 1901, Juana Belén and Elisa Acuña founded the first newspaper with a critical voice written by a woman: Vésper, Justicia y Libertad. There were several publications where women wrote, of course, but they were aimed mostly at other women focusing on teaching and giving advice on how to be feminine, good housewives, or guardian angels of their homes. Culturally, socially, and politically speaking, during Juana Belén’s time, women had no choice but to be feminine and to be mothers in order to be considered “decent.”

When women still couldn’t vote or occupy positions of power, Juana Belén started a political, anticlerical, anti-Porfirian, and liberal newspaper that allowed her to express her ideas. On August 23rd, 1901, Ricardo Flores Magón dedicated an article to her in his own oppositional newspaper, titled «Vésper, a alabar a Juana Belén» (Vésper, in praise of Juana Belén), writing: “The virile colleague Vésper, from Guanajuato, which is skillfully directed by the enthusiastic Mrs. Juana B. Gutiérrez de Mendoza [...] is a bundle of virile energies. Our respectable colleague’s columns are nourished by advanced ideas…” As her main biographer Ana Lau Jaiven (2023) points out, anarchists highlighted the “virile” as a masculine condition, as if only men could be brave and confront the dictator. Juana Belén certainly did not fear ending up in jail for what she thought. In fact, she was imprisoned for her first essay, published on November 2nd, 1898, in Diario del Hogar, where she denounced the unfavorable conditions of the mine workers in La Esmeralda, Chihuahua. Her denunciations against the mistreatment and precarious labour conditions of workers, peasants, and Indigenous people led her to be imprisoned many times.

In 1909, she co-founded the Club Político Femenil Amigas del Pueblo (Friends of the People Women’s Political Club) and the Club Hijas de Cuauhtémoc (Daughters of Cuauhtémoc Club). In 1910, along with the “sandwich women,”2 Juana Belén demanded Madero female suffrage (though she would later change her opinion on it). She took part in the Ayala Plan, joined the Zapatistas, and was named Coronel. According to Hernández Carballido and Alicia Villaneda (1994), the naming came as an endorsement gesture from Zapata when Juana Belén commanded the shooting of a member of her division that had raped a woman. Zapata backed her up after some people complained and, according to Marta Lamas (2020), issued an order that severely sanctioned any abuse of women (except if they were an enemy). Juana Belén stepped up against Carranza when he tried to impose his own hegemony. She was a restless Zapatista fighter, completely convinced that Indigenous people were the soul of Mexico and that education was the only way for the Mexican people to reach freedom. Juana Belén felt especially identified with the Indigenous people in Mexico; her Caxcana grandmother voluntarily became mute after she was raped by a Spaniard.

In 1922, Juana Belén began to organize the Acción Femenil (Female Action) group and joined the National Mexican Women’s Council. She was appointed missionary professor in Jalisco and Zacatecas that same year. In 1926, she was named inspector of rural schools in Zacatecas and became part of an Indigenous collective called the Caxcanes Council.

How is it that, with as lengthy a career, her name is still not present in books alongside Zapata, Flores Magón, or Madero, as a precursor of the Revolution? What would it be like to learn about Juana Belén in elementary school, next to the “great heroes” of the Revolution? What would it be like to not learn about the great heroes but rather about the collective struggles that brought Díaz down?

There are many answers to these questions. On the one hand, I suppose that I was simply not taught this in school because it is not believed that women are capable of such greatness. Even when I share the story of Juana Belén with friends and colleagues, the first response is: I can’t believe it! Ana Lau Jaiven has pointed out how Juana Belén conceived of herself as a political citizen with a voice, at a time when the State did not legitimate women as citizens. I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say that I strongly believe there would be less violence against women today if we were taught about the Indigenous collective struggles supported or spearheaded by women in the most important moments of our country’s history. I don’t mean to say that only representation matters. Yes, the struggle begins by having more female representation, but Juana Belén knew that what had to change—what still needs to change—is the structure. On May 8th, 1910, she wrote the following against the reelection of Díaz: “Do not think that we believe (as many delusional people whose names we could cite here) that it is enough for anyone to replace General Díaz for our people to be free [...] ‘the fall of the tyrant is not the fall of tyranny.’” Juana Belén knew that it was the structure founded on inequality that had to change, which not only meant taking Díaz out of power. We are still facing the tyranny imposed by Díaz in terms of corruption and a truncated democracy. We don’t need more representatives, women or men, cis or trans, who will continue enabling patriarchal policies while in power. We need to continue fighting to end the patriarchal tyranny, as Juana Belén did.

Due to ideological differences and power struggles, there was an irreconcilable rupture within the anarchists and liberals’ faction. These struggles have existed throughout history, however, I think it’s important to note that, when a brave woman is involved, the most “legitimate” way to discredit and humiliate her is always to scar her “honor” or stain her “good reputation” using her sexuality, a common practice during the 19 century.

Within this context, on June 15th, 1906, five years after praising and exacerbating Juana Belén’s bravery as synonymous with “virile,” in the same newspaper (Regeneración), Flores Magón tried to debunk her as “vile” due to her sexuality. An entire page was dedicated to uncovering and discrediting Juana B. Gutiérrez de Mendoza. The ideological and power differences had surged when Juana allied herself with Camilo Arriaga, especially since it had to do with money. Ricardo Flores Magón assures he disassociated himself from Juana and “her companion Elisa Acuña y Rosete when we learned of her political mercantilism and her repugnant vices.” He goes on for numerous columns, establishing that he must “defend his honor,” justifying why he goes on to explain the “disgust” that Juana B. Gutiérrez and Elisa Acuña y Rosete’s treason stirred in him.

Apparently, many stuttering friends had warned them about Juana, but according to Flores Magón, it wasn’t until “[we] witnessed with OUR OWN EYES the black rites conducted by those Sapphic priestesses, we did not hesitate to throw them away from us, to cast them away so that later on the cause that we love so much would not fall on reproach and disgrace…” With adjectives such as “nauseating,” “disgust,” “venomous serpents,” but above all, by calling them “traitors to nature who give themselves over to monstrous and stinking delights,” Flores Magón assures that Juana and Elisa surrender to Sapphic pleasures. He continues: “Have we spoken harshly about these women? Yes, we have spoken harshly. But we’ve said it before, to defend our honor, we are unyielding…”

Beyond asserting whether Juana Belén and Elisa Acuña were a couple or not, what I want to emphasize is that it is based on their sexuality that Flores Magón defends his own honor. It is above all the sexual dimension that justifies for Flores Magón—and, surely, for his readers and other people of his time—that Juana Belén cannot be trusted, for “which cause could be enhanced with such monsters as its defenders? What pure and honorable banner could be lifted immaculately from the filthy hands of these women? What love for humanity could those that despise and offend it with such sterile and hateful vices have, which not even animals desire?”

“Virile” is an adjective that qualifies the qualities desired in a man, but it was thought that they were inherent to their gender. In Masculine Domination (1998), Pierre Bourdieu argues that it is precisely the concept of “virility,” that upholds the dominant notion of traditional masculinity.

The hegemonic male gender, understood as strong and dominant, utilizes virility to naturalize certain behaviors, attitudes, and subjectivities. On the one hand, it was used to praise Juana Belén, since it was not thought that a woman could be capable of facing up to Porfirio Díaz. But this same virility was the basis for stigmatizing her as “monstrous, repugnant, disgusting.” I am unsure as to the extent to which the discrediting of Juana Belen’s masculinity contributed to the exclusion of her figure from history books.

If we don’t know anything about the lives of, let’s say, traditional women—in the sense that they comply with the imposed norms around femininity, such as getting married and having children—how can we expect to be taught about the masculine women (considering that, in those times, writing or wanting to be a doctor meant being masculine) who did not stick to merely procreational sexuality? A year before, on July 23rd, 1905, a poem signed by Alacrán and dedicated to Juana Belén appeared on El Colmillo Público, titled “A falta de pan, buenas tortillas.” A year later, in the same newspaper, a cartoon captioned “Juanita’s Writing Office” was published. On the left side, two women were kissing, one seated on the legs of the other. On the other side, there was a woman kneading dough to make tortillas directly on the metlapil, and next to her, over the stove, a comal with tortillas. Fausta Gantús, in an article titled “Juana the Tortillera,” published in El Universal in 2022, suggests that the woman making tortillas is also the one seated in the other woman’s lap, kissing her.

Unfortunately, we don’t know much about Juana Belén’s line of thought. We lack primary sources for her writings. Her newspaper Vésper, for example, is not available. Regarding secondary sources, there is an image of a page of Vésper’s July 1st, 1906, edition where Juana Belén responds to Flores Magón, assuring that no one is interested in her sexuality (Jaiven 2023). We’ll never know if Elisa Acuña was Juana Belén’s partner, but these newspaper articles reveal an obsession surrounding the sexuality of women who dared to transgress the established norms on the grounds of femininity. Women who challenge the delicate virility of Magonistas in particular, and patriarchy in general, which is why we don’t learn about them in history classes. Women who exercise their sexuality are interpreted as evil, despicable, and unscrupulous, but these are the examples we need in history books.

Even though Juana Belén expressed her objection to Vasconcelos’ educational policy for considering it to be unifying and homogenizing, she was named a missionary teacher and spent her last years within the realm of political struggles dedicated to education. From 1937 to 1940, she lived in Michoacan as director of the Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez Female Industrial School. Upon her death in 1942, her family sold her typewriter to pay for her burial.

Juana Belén is planned to be one of the 12 heroines whose sculptures will be placed along Paseo de la Reforma, after Mexico City’s government took down Columbus’ monument in 2021; however, I have the feeling Juana Belén would want to be recognized not only as a statue, but as part of a struggle that is still very much alive.