Going to the Park is as Important as Entering a Museum: Pablo Barriga's Artistic Practice

07/13/2023

Barriga's imprint has to do with ideas and postures, not with a style [...] It is only in the last two decades that research has been carried out that situates the importance of his work for the renewal of the artistic field, placing it as an antecedent of art, and community practices.

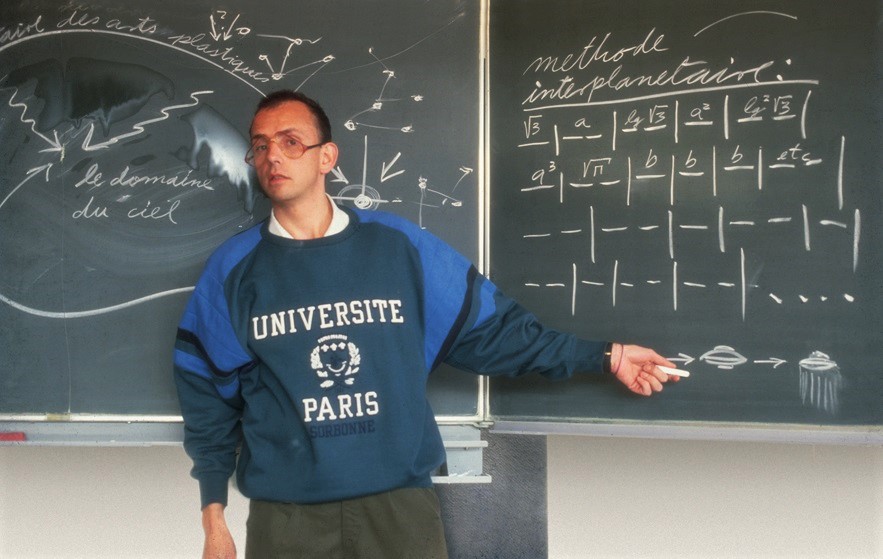

Pablo Barriga (Quito, 1949) is one of the forerunners of contemporary art in Ecuador, a field to which he contributed as an artist, professor and essayist through a discussion on the place of art in society. Since the 1980s, his practice has been characterized by transgressing the boundaries of academicist artistic genres, questioning art institutions, appropriating unconventional spaces and opening possibilities for the viewer to reinterpret their role. Particularly in the Quito scene, Barriga's ideas have influenced the generations of artists who were trained at the Faculty of Arts of the Universidad Central del Ecuador, where he was a professor from 1982 to 2011,1 and at the Faculty of Architecture, Design and Arts of the Pontificia Universidad Católica, between 1994 and 2010.

Barriga was my painting professor at the Universidad Central, a training space founded in 1968 that was very much anchored to the tradition of the Fine Arts Schools and the prioritization of technique. He also graduated from this university in 1980 and almost immediately became a professor. However, his postgraduate studies at Saint Martin's School in London in 1983 gave him the opportunity to travel to other cities, while his reading habits gave him more tools to guide his students. In the painting specialization, the possibility of exploring and experimenting beyond the medium was encouraged in his professorship, as well as in that of Mauricio Bueno, an Ecuadorian artist who introduced conceptualism in the 1970s.2 The figure of the professor-artist, in both cases, became a guide to expand the notions of painting and even shift it towards installation and performance.

Barriga's imprint on those of us who were his students has to do with ideas and postures, not with a style. His works are not based on the persistence of a language, instead they emphasize processes, discuss the elevated status of the artistic object and propose an approach to popular aesthetics. Several of his works are little known, as they were not intended to circulate in the art world.

It is only in the last two decades that research has been carried out that situates the importance of his work for the renewal of the artistic field, placing it as an antecedent of art, and community practices.3 This text is based on the curatorship I did for his anthological exhibition, in the framework of the Mariano Aguilera Lifetime Achievement Award he received in 2015.4 Here I will address some of Barriga's interventions in the public space to reflect on the relationships he builds between art and society.

Public Space as a Place of Enunciation

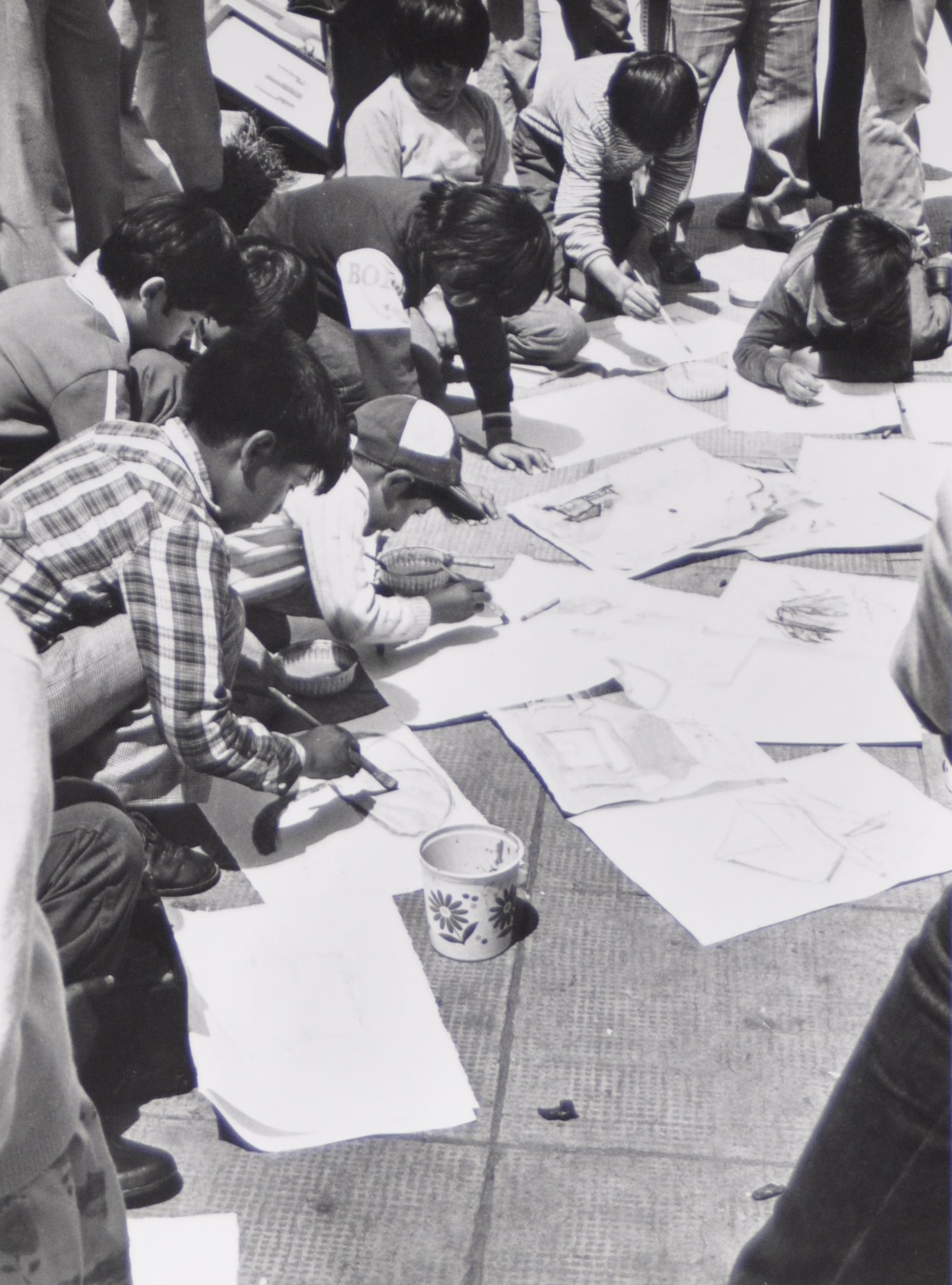

The artist's position has its origins in the Marxist orientation of his family, influenced by socialist and communist ideologies. A year after graduating from the university and having had two individual painting exhibitions, he proposed the collective project Arte en la calle (1981-1982), which sought to establish a direct communication between artists and the public, using parks and squares as stages for the presentation of artistic works5 that included dance, theater and music. Outside museums and galleries, art was proposed as an object of communication and not as an object of worship or merchandise. However, the focus was on creating spaces for people to express themselves through drawing, painting, ceramics, tapestry, and engraving. As Barriga said in the group's manifesto: "The only way to democratize art is to offer the possibility of artistic expression to the people themselves."6 After several editions, the group gradually disbanded and the project was co-opted by the official municipal programs.

In the following years, from his individual practice, Barriga returned to the park as a place of transit, leisure and dialogue that will be a recurring scenario throughout his career. As an example, in his pioneering incursions into the language of performance, making his body a place of political enunciation. The action entitled Tricolor (1988) consisted of dressing up in a suit and adorning himself with ribbons commemorating the national flag as he walked through La Carolina Park dragging objects brought from home, which became dirty along the way. For Barriga, this walk was an act of nonconformity with the Febres-Cordero government (1984-1988) which, in order to counteract subversive acts of social opposition, institutionalized violence through repression and forced disappearances.

Another emblematic action by the artist is Mordaza a la cultura (1993), a protest against the situation of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana. Dressed as a street actor in the park, he covered with bandages the bronze bust of Benjamín Carrión, famous literary figure and founder of that institution in 1944. In a context of neoliberal measures that implied budget cuts for culture and the privatization of public companies, Barriga's action appeared on the front page of the newspaper El Comercio, giving visibility to this issue. However, the ambiguity of this image between the gag and the mummification of the so-called "manager of national culture" has made this action transcend in time as a criticism of cultural officialdom and the conservatism of the elites who manage it.

Barriga sought to displace his practice from conventional spaces, rejecting the mercantilism of the galleries of the time. Since 1991, he appropriated the abandoned and destroyed space of the Old Military Hospital to turn it into his workshop and exhibition space.7 In the exhibition Ambientaciones (1995) he linked the deterioration of the place with the use of poor and ephemeral materials, which fractured the idea of value around art as a luxury object accessible to a few. Another example in this line of search is his landscape-painting exhibition in the courtyard of the San Lazaro Psychiatric Hospital in 1999, during the height of the political, social and economic crisis that led to dollarization. The exhibition was mainly aimed at those who lived in the psychiatric hospital, in Barriga's words, "the people locked up for not matching the normality of others."

The Value of the Popular

Finally, it is necessary to highlight his contribution in valuing the popular as an aesthetic that contrasts with the weight of the colonial, in a city like Quito, whose historic center was declared a World Heritage Site. In contrast to the conservative positions that vindicate the Hispanic, white-mestizo legacy and promote the immobile preservation of the historic center, Barriga's gaze focused on the streets' movement and the creativities of its inhabitants. In several of his works from the 1990s he uses assembled everyday objects: a bread mold, wooden toys, wedding cake decorations that were rearranged to recirculate in other contexts. Thus, in the exhibition Pasado y presente (1995) he succeeded in inserting them in the Museo de Arte Colonial de la Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana through an intervention that consisted of 10 installations that dialogued with the museum's collection. Objects acquired in bazaars and markets, associated with "bad taste," were contrasted with the gilded altars and religious iconographies.

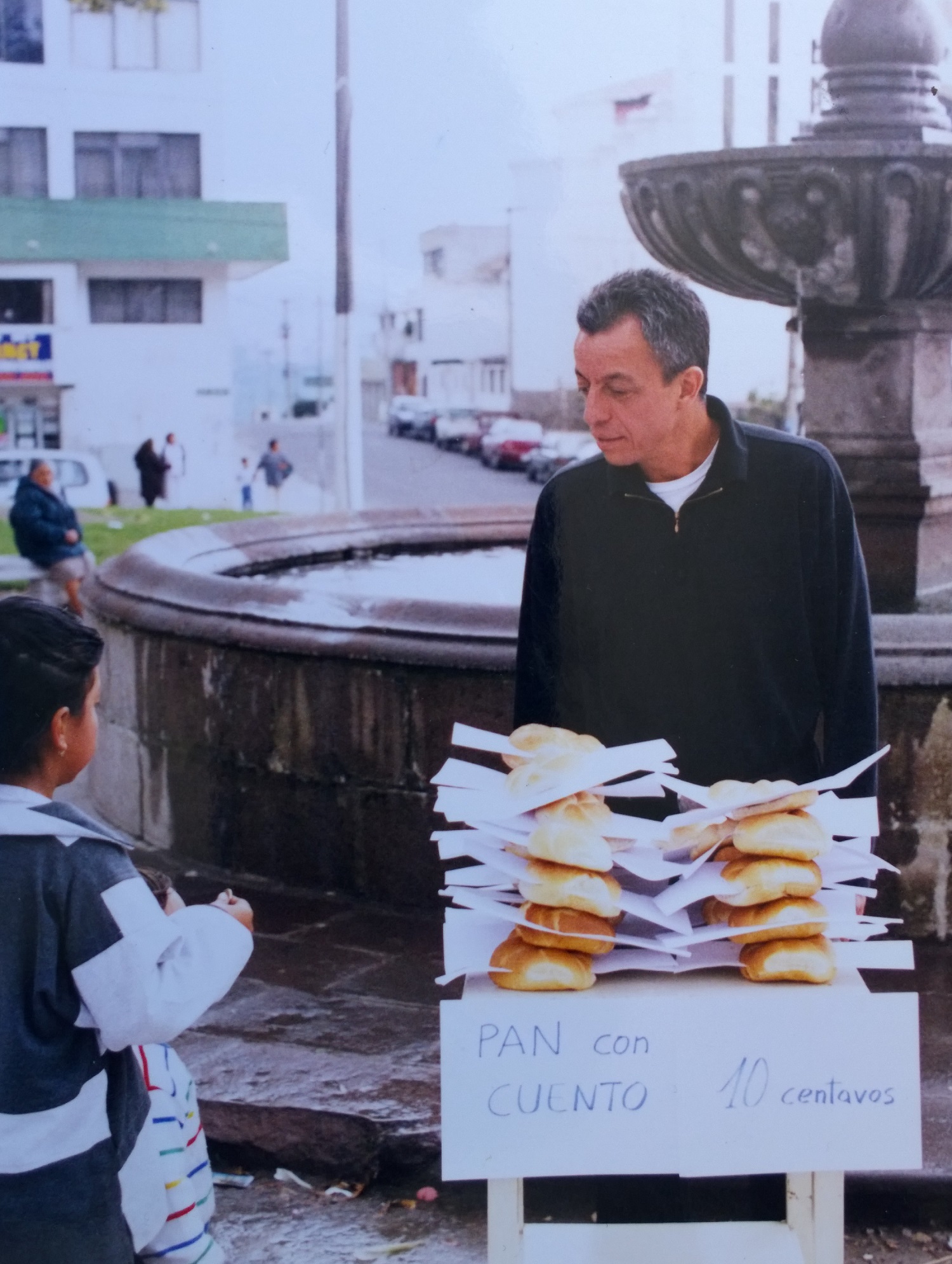

In the unpublished research entitled El objeto callejero en la ciudad (1997), Barriga reflects his pioneering interest in appreciating the aesthetics associated with the daily trades in the historic center. The conclusions of that research pointed out that aesthetics went hand in hand with functionality, without gratuitousness or waste. Almost ten years later, Barriga carried out an action that poetically articulated his sensitivity towards the popular and his political position. In Pan con cuento (2006) he combined his interest in literature and the arts to approach the passers-by in his La Floresta neighborhood. Inspired by his observations of street objects, Barriga set up a simple stand of sandwiches filled with his own writings, which were sold for 10 cents. The action was also a questioning of art's value by setting up a business at a loss, considering that the cost of the raw materials (bread and photocopies) exceeded the selling price. However, for the artist the greatest gain was the distribution of his writing in social sectors where education is a privilege and art a luxury.

Barriga has remained present in the artistic field with exhibitions, texts and actions. His contributions to conceptualism arise from a sustained pictorial practice that permanently overflows into other manifestations. In this sense, his interventions in the public space are forms of irruption in everyday life that inspires estrangement and reflection.

One of the activities proposed by the artist-teacher that his students remember most was the visit to the park, which was as important as entering a museum. The parks were a place to be distracted, to have fun or to linger. They were a place to observe nature in the city and the daily dynamics of passersby, children, schoolchildren, vendors, street artists, and other inhabitants—an open space to share with those outside the systems of art legitimization. Barriga's artistic practice and his work as an educator converge in this posture of generosity of knowledge and intuitions.