Valcárcel: Brutally Lucid (and Generous)

12/06/2022

Implicit in Valcárcel's proposal for a movement that summons creativity to contribute to the construction of a more democratic society, is a new relationship between creativity and politics. This proposal is articulated out of his rejection of the association between artist and genius or virtuosity, [...] because he considered that it fostered an excluding idea of creativity.

Throughout his career, Roberto Valcárcel (La Paz, 1951 - Santa Cruz, 2021) attributed great importance to creativity due to its potential to transform Bolivian society, a country marked by dictatorships and with a population that was mostly indigenous, poor, illiterate and with a vertical and memoristic education.[1] The visit of the famous critic Marta Traba to La Paz—as jury of the 1977 INBO II Biennial—shook the local art scene with an article that was published in the local press, in line with her theory of the art of resistance, which left Bolivian art and its main representatives of the time in a bad light.

Although Valcárcel agreed with the perception of stagnation pointed out by this art critic, he had an irreverent and completely different position on how art should relate to society and politics. He did not share all the points of view mentioned by Traba and the rest of the international jury, which was the formula of the original painting, resolved with virtuosity, with a message linked to a Latin American identity.[2] Nor did he share Traba's aversion to what she called “decadent art,” Latin American art that “imitated” the novelties of the New York (or European) avant-garde of the time. The Trotskyist critic and professor Carlos Salazar Mostajo, an influential and determining presence in the Art career of the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA) and in the Escuela de Bellas Artes de La Paz, had also raised this rejection.[3]

Living in a homophobic Bolivia during the Cold War and in a Germany divided between Western capitalism juxtaposed with Soviet socialism were equally determining experiences in the construction of his lucid view of the world.

Valcárcel's is a gaze in which underlies a questioning of authoritarian behavior, based on Herbert Marcuse's analysis of repression. He found revealing relationships between these ideas and those of Joseph Beuys on democracy. From there he imagined creativity as a useful paradigm for the revitalization of a "moribund" art scene, but above all necessary in this difficult social, educational and political context.

Creativity As Ethics

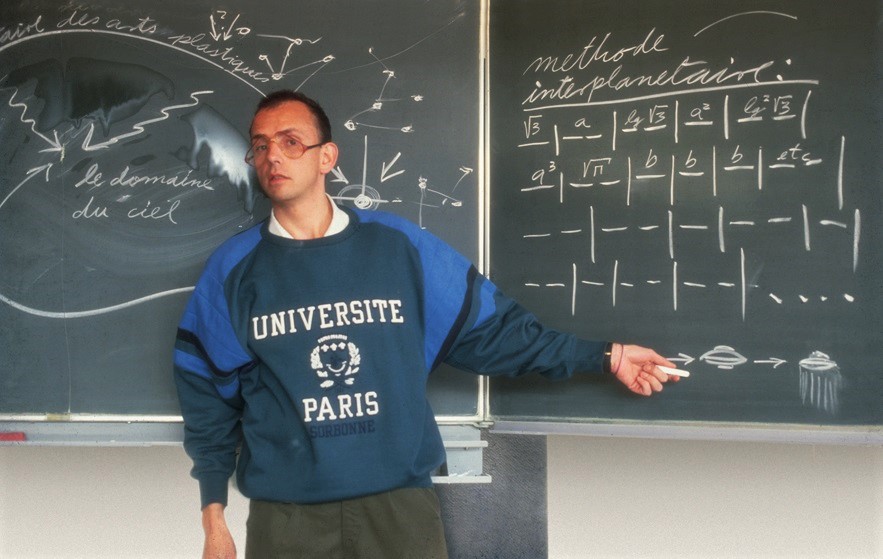

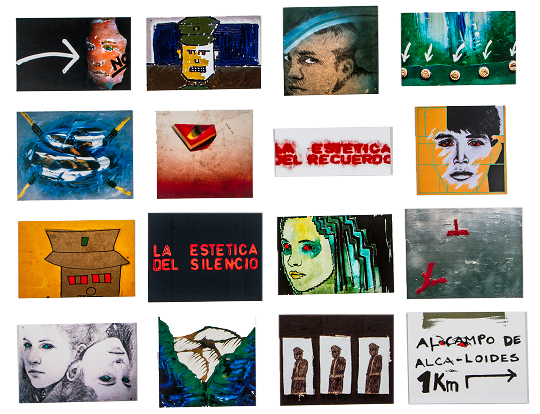

The first Festival Boliviano de Arte Experimental of 1983 was one of Valcárcel's most ambitious creative-pedagogical projects. The Festival took place 10 months after the recovery of democracy and matched the end of Valcárcel's brief directorship of the Art Department of the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (1982-1983), a juncture that triggered a profound change in his work. Since then, he assumed, in a forceful manner, art as research oriented to the production of thought. The Festival, organized by Valcárcel and his art students, as well as some other independent artists,[4] was open to all those interested in “participating and experimenting with new forms and contents.”[5] It took place over 14 days in galleries, in central and busy points of the streets of La Paz, on the state television news channel—Canal 7—and at “any time, anywhere.”[6]

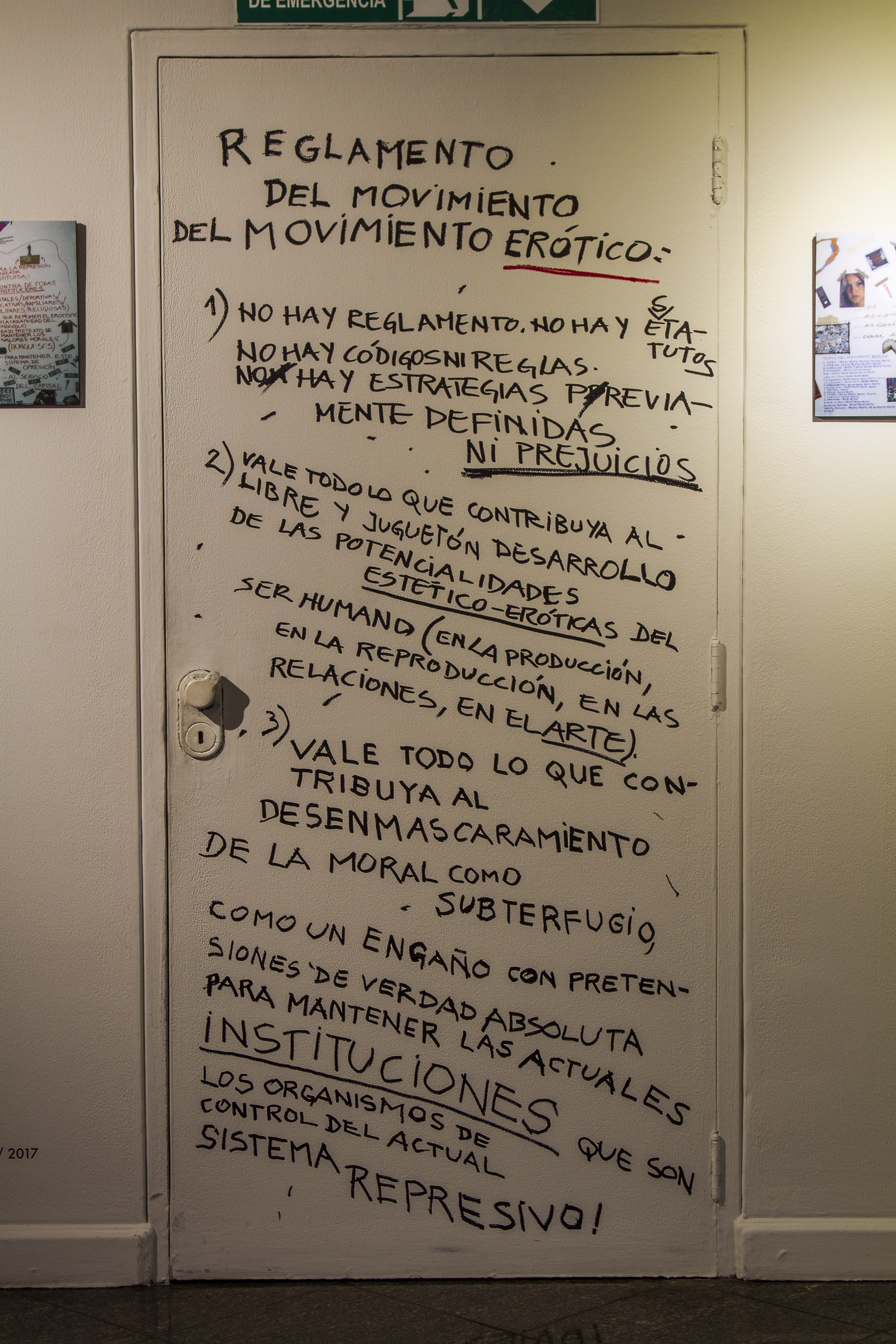

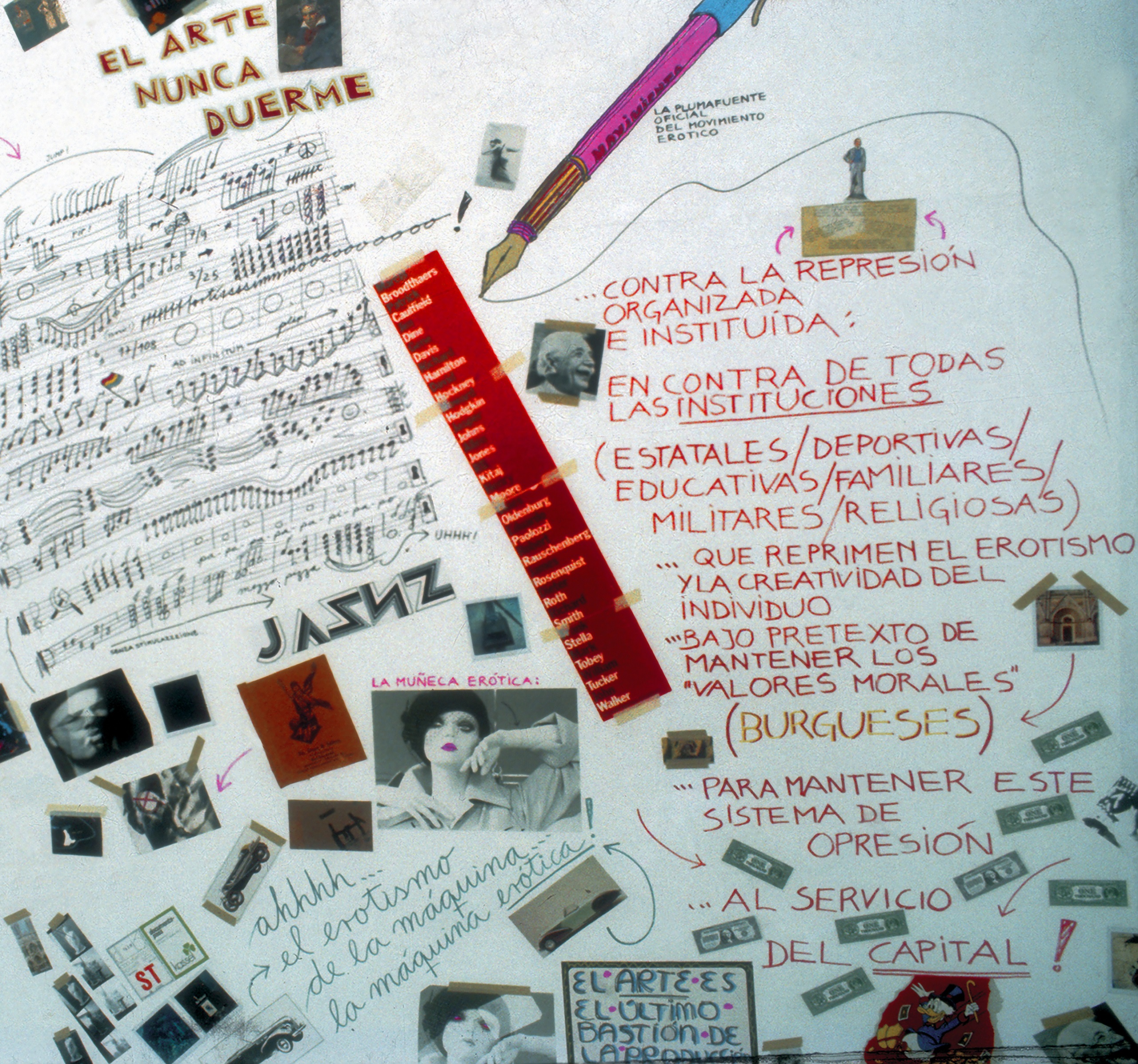

In line with one of the possible definitions of experimental art [7] proposed, Valcárcel's Movimiento erótico, a conceptual, theoretical and interdisciplinary work, suggested a vanguard according to Marcuse's approach, in which art would be the main activity of a non-repressive society.[8] Composed of 20 sheets of cardboard, with handwritten texts in markers, schematic drawings (children's style) and magazine clippings, Valcárcel “demonstrated” that it was possible to make art without academic training, an unusual idea in the context at the time. In Movimiento erótico, he identified four approaches related to an ethical position on creativity in artistic practice and pedagogy: we are all (potentially) artists; art as research; radical creativity; and a critique against repression-authoritarianism-power.

Creativity and Politics

Implicit in Valcárcel's proposal for a movement that summons creativity to contribute to the construction of a more democratic society is a new relationship between creativity and politics. This proposal is articulated from his rejection of the association between artist and genius or virtuosity, so deeply rooted in the local artistic environment, because he considered that it fostered an excluding idea of creativity that was very useful “for those who are interested in preventing people from being creative, both in art and in politics.”[9] He expressed this in another of the slides of the Movimiento erótico, in which he “established” that creativity is an essential component of non-authoritarian societies.

In tune with this proposal, the protagonists of the Festival Experimental were mainly Valcárcel's students. Of the Movimiento erótico, signed by “Producciones Valcárcel,” practically no record remains—it was presented as one of more than a dozen “events” (exhibitions, demonstrations and actions, a colloquium and debates in the streets), which conceived art as research in process. Although the Festival was a creative experiment that placed the students in the professional limelight, the works they produced also took into account the spectator as co-creator of the work. Along these lines, Rina Dalence's Manifiesto del Arte Boliviano—made up of wooden pieces, each with a word—invited the public to create a movement [10] whose purpose was, in her words: “to end the myth that separates the artist (as a blessed being who has a gift) from the public (a non-creative and passive spectator).”[11]

Creativity As Eroticism and Radical Criticism

In line with the invitation for all of us to be artists, one of the slides of Movimiento erótico entitled “Reglamento” (Regulation), raises three fundamental ideas around creativity and its relationship with authoritarianism, repression and democracy. It begins with a kind of warning that ironically states that “there are no regulations, there are no statutes;” undoubtedly, a call for autonomy and to resist bureaucracy in general, understood as repressive and anti-erotic, in particular, that which came from groups such as the Bolivian Association of Plastic Artists, of which he was a member. He continues with the following statements: “There are no codes or recipes. There are no previously defined strategies, no pre-judgments,” in which he alludes to the artists' secrets that contribute to the myth of the artist-genius that Valcárcel rejects. Even more significantly, he calls to assume each creation as a research with its own specific strategies and methodologies, in other words, to assume artistic practice as research.

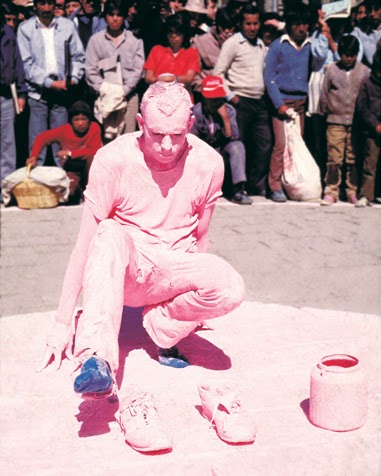

In the same text, Movimento erótico calls for a radical creativity. Its “anything that contributes to the free and playful development of the aesthetic-erotic potentialities of the human being (in production, in reproduction, in relationships, in art)” is a call to what Marcuse defines as a full-body “eroticism.” This association of creativity with the body in all its dimensions had already been glimpsed in the collective and experimental work that Valcárcel carried out with Gastón Ugalde and his architecture students, the result of which was presented at the São Paulo Biennial in 1979. The work was the result of a process of collective creation, based on excursions to the outskirts of the city of La Paz, in which, according to Ugalde, “we made a kind of performance, actions, installations, and recreated men hanging, tortured, and photographed them.”[12] At the same time as referring to the repression and state control of the youth in the streets, the generation of these images meant a “liberating” act, based on the bodies of young people from a demure society, not very expressive and not very happy, like the one in La Paz. Playing at posing for the camera was a fun moment of expression—erotic, in the Marcusian sense—of connection with one's own body and that of others. In this regard, Ugalde recently explained that:

There was a motivation to work, to leave aside individual expression and work in a communitarian way, in a joint way, and obviously all this had to come from what was happening in the rest of the planet, with the movements of the democratic revolutions, of the student movements, the strengthening [...] of a cultural revolution that was born in the sixties but that in Bolivia was just taking hold in the mid-seventies, with free thought, sex, rock 'n' roll, all that liberation.[13]

In these cathartic actions, Valcárcel played a catalytic role, because he inspired a lot of confidence, “he had the virtue of being able to summon” urban youths, part of a generation that could not express themselves freely in the streets, to “lend themselves to do certain actions” in “strange situations.”[14]

Finally, in its “Regulations,” Movimiento erótico proposes creativity as critical thinking that allows to uncover interests to control individuals: “Anything that contributes to the unmasking of morality as a subterfuge, a deception with pretensions of absolute truth to maintain the current institutions that are the control bodies of the current repressive system is worthwhile.” The divergent thinking proposed by Valcárcel makes it possible to question, for example, the morality of art in Bolivia and its rigidity insofar as it is “installed” as “truth” in its institutions: in a morality that underlies the idea of a Bolivian art with a univocal and idealized identity; or in an anti-imperialist morality, opposed to any other idea or social function of art. This explains why a group of students from the Escuela de Bellas Artes, where Salazar Mostajo's ideas prevailed, decided to go to the local newspaper El Diario to denounce the Festival for promoting immorality or the values of US-American and European capitalism with the following words: “What is exhibited in the EMUSA gallery is not art but expressions of painters like Roberto Valcárcel, who show opulence, ridiculousness, immorality, the vices of a decadent society. These attitudes totally undermine the experimental art festival.”[15] It should be clarified that the influence of Salazar Mostajo's thought in art education used to materialize in works that, in broad strokes, did not depart from a nineteenth-century academicism within the framework of a national identity associated with the class struggle.

Unfortunately for the development of contemporary art in Bolivia, in 1983 the “revolutionary” group was installed at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés with a conservative and old-fashioned teaching, opposed to contemporary art, and from a memory-based art history.[16] Thus, in the model drawing class, men could only pose in “heroic posture” and women in “delicate posture,” according to artist Guiomar Mesa.[17] Thus, the normalized sexism in society, an obscurantist morality in the artistic field and its institutions, was reiterated in the Arts Career. Such was the weight that this conservative moral had in that context, that the director of the Casa de la Cultura closed one of the exhibitions of the Festival because the work of a student, Rosario Ostria, had been made with panties.[18]

Epilogue

Valcárcel dedicated the rest of his life to teaching at universities and giving courses on creativity, photography, art history and drawing in his studio. In 1988, in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, he directed the SEAMOS program in the popular neighborhood known as Plan 3,000, where he gave creativity workshops to some 2,300 young people.[19] This neighborhood had been created to shelter those affected by the 1983 flooding of the Piraí River and became the main point of arrival of migrants from the altiplano to the city. In the 1990s, he sought funding for his Pintovia art school project, a venture he was unable to secure funding for. From then on, he was a mentor to the main managers and curators of the most important contemporary art projects in Bolivia, such as Patricia Tordoir, Cecilia Bayá, and Raquel Schwartz. He also taught up to eight subjects per semester at a private university in Santa Cruz, and, for that reason, he bought the Miami lottery weekly, hoping to have time to dedicate to his work. He questioned his legacy as an educator. He liked, however, the possibility that he might have had an impact on his one-time student, Maria Galindo, of the Mujeres Creando collective.[20] While she never knew it, Galindo also liked to think of him as a teacher, as the person who “taught her to look at the world.”[21]

Until the end, Valcárcel maintained that creativity was a tool for empowerment and that it should be used for a better world. Thus, in his last interview, from the Hospital Obrero in Santa Cruz, he proposed:

“Let's start thinking, drawing or designing what could be fantastic, the most fantastic thing ever thought of—and for what? So that art, design and also medicine can progress. That will allow us to cure this pandemic all over the world; thanks to human fantasy and the capacity of imagination we will cure it.”[22]