Participatory Art as an Educational Action

03/06/2023

The viewer’s participation was a way to create a space for sensitive interactions that would allow a change in our way of being in the world, to "awaken the spectator from his lethargy and passivity before life [...] and, likewise, to enable the emergence] of a better way of thinking, feeling and loving.”

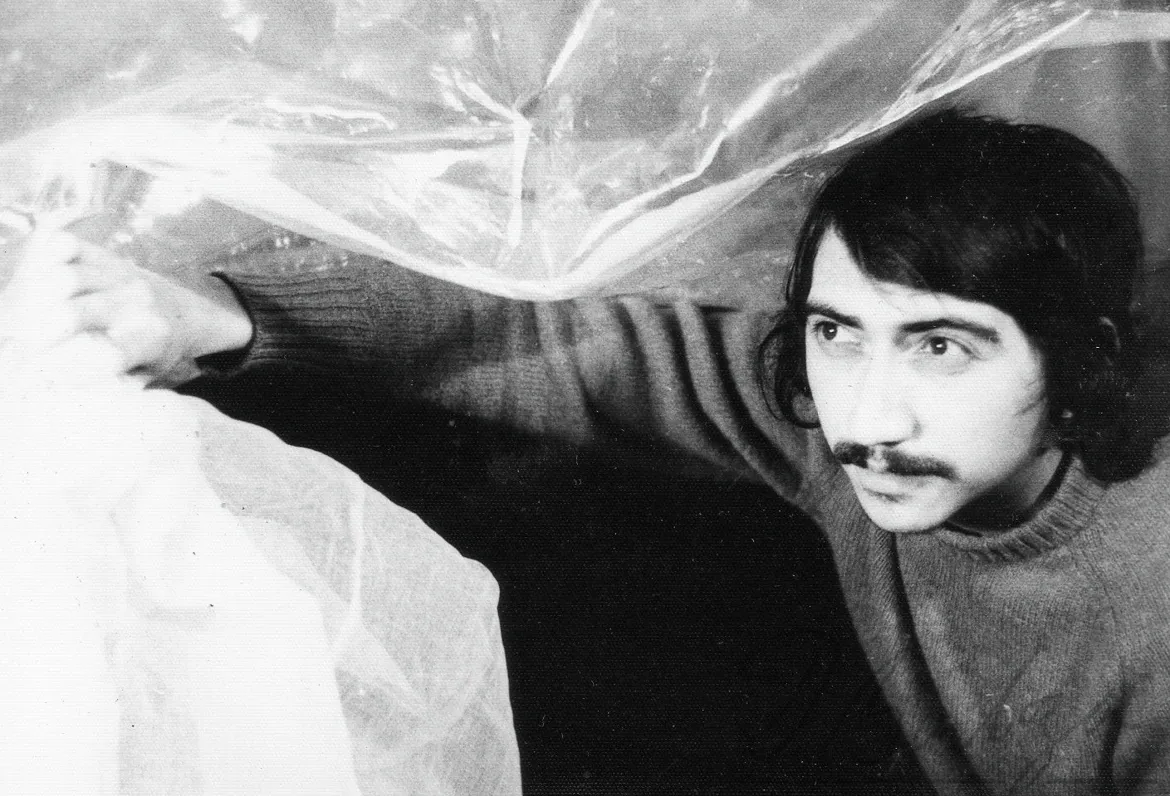

In late 1968, Diego Barboza (Maracaibo, Venezuela, 1945 — Caracas, Venezuela, 2003) traveled to London in search of a context that would allow him to channel his concerns about the development of an art that could go beyond traditional object-centered practices and effectively integrate the audience into the artistic act. Some of his considerations in this regard had emerged a year earlier when he exhibited works that required the viewer's participation and interacted openly with the visitors.1

The 1960s changed the social and cultural face of the West. Counterculture movements had infused all fields; in art, this "revolution" manifested in the irruption of conceptualism. Artists began to produce works and events in which ideas took precedence over formal or visual aspects; hence, the artistic object and its contemplative perception were displaced by a focus on the creative process and an interest in interaction with the audiences.

Among the various tendencies amassed by conceptual art, ‘action art’ is defined as a type of practice in which bodily actions—personal or collective—constitute the work itself. The creative process is laid bare through the movements or paths, as well as the dynamics generated by the interaction of the body—or bodies—with the physical, social, and/or psychological space. These events allow room for chance or play and are ephemeral and unrepeatable. Thus, the artwork becomes a 'happening.'

Soon after he arrived in London, Barboza visited Hélio Oiticica’s retrospective exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, where he confirmed his intuitions about action art. In this exhibition, the Brazilian artist had gathered works that revealed his interest in turning art into an experience through the visitor's multisensorial participation. The environmental installations Tropicália and Edén2 captivated the Venezuelan artist. The former was a labyrinthine and experimental space composed of two penetráveis that resembled the precarious architecture of the Brazilian favelas; there were also parangolés, plants, parrots, poems written on objects, and a television set, all arranged on a blanket of sand. The array of tropical images and references to underdevelopment not only stated a critique of the Brazilian paradise stereotype but also encouraged a new way—lively, sensorial, placing the spectator at the center—of making and experiencing art. Edén, on the other hand, was a large environmental installation that brought together participatory works such as tendas, bólides, and parangolés. Here, Oiticica advanced the concept of ‘crelazer’—a neologism that mixed the Portuguese words crer (believing) and lazer (leisure)—3 which was linked to the spectator's creative relationship with the space and the elements contained in it. By promoting free interaction, Edén sought to elicit non-stereotyped behaviors arising from the everyday and freed from any purpose other than the body's own needs,4 in order to contribute to unburdening the individual from all conditioning.

The participatory works that Barboza would later develop were influenced both by the ‘liberating pedagogy’ proposed by Oiticica and by his inclusion of popular cultural manifestations. In fact, Oiticica's oeuvre brought Barboza definitively closer to one of conceptualism’s fundamental aspirations: to make art an instrument capable of enabling the unlearning of the alienated ways of being. The viewer’s participation was a way to create a space for sensitive interactions that would allow a change in our way of being in the world, to "awaken the spectator from his lethargy and passivity before life [...and, likewise, to enable the emergence] of a better way of thinking, feeling and loving. [...] In other words, to link art with life,"5 on an individual, social, and political level. On the other hand, Barboza found in popular manifestations—which he intertwined with folkloric elements of culture—a language that brought him closer to people and that allowed him to establish a frank communication, in addition to relating experimental participation with "autochthonous" forms of integration.

The playful aspects are relevant in Diego Barboza's conceptual work and can be studied departing from the notion of crelazer, since leisure and play produce completely free creations, spark imagination, and subvert the ordinary experience. In 30 muchachas con redes [30 Girls with Nets] (1970), Barboza gathered a group of friends whom he covered with fishnets and instructed them to walk the streets, acting enigmatically in front of passersby. Although he would gradually eliminate the instructions in his London expressions,6 compelling an "atmosphere of play, mystery, and festivity"7—emphasized by the use of props such as nets, hats, or cloths—this would remain a characteristic of such events, as would the artist's growing interest in the free integration of passersby into the experience. The game dynamics was also present in actions such as La célula humana [The Cell] (1971), in which Barboza fostered a chain of communication by mailing numbered sheets of paper with the reproduction of the drawing of a cell. Those who received it had to contact the person whose cell number preceded or followed theirs. In Danger! King-Kong (1972), the artist handed out a poster with an image of the gorilla and the word ‘DANGER’ printed on it. He gave clear instructions to cut it out and introduced a fictional element, stating that the ape would attack those who failed to do so. Playfulness was also part of actions such as La caja del cachicamo [Armadillo Box] (1974), where music and dance emulated the diversiones from Venezuelan folklore—popular manifestations called this way because of their playful and joyful character.

Unlike Oiticica, most of the actions carried out by Diego Barboza were realized in public spaces: in London, in streets, squares, and markets; in Venezuela, in parks. In Put a Net and Come Along (1970), the artist invited the audience to paint and exhibit their works at the London New Arts Lab, and then to go out for a walk wearing cloths, nets, and paper flower hats. Other events held in the British capital, such as Expresiones en el mercado [Expressions at the Market] (1970), The Centipede (1971), or People Tied Together (1972), and La Caja del cachicamo [Armadillo Box], carried out in Venezuela, also integrated participants with passersby into different places of the city. The public space, taken like this, was experienced in a novel way, triggering reactions that entailed a transformation of everyday life in themselves. The socio-cultural maps established by the spheres of power are visible in the design, arrangement, and stratification of the spaces that are common to all. Street events provoke a sensitive dynamization of the environment, which is also “proof that art alters people's daily behavior”8 and that people's behavior somehow transforms the space. The street event, thus, functions as a device that makes “unlearning” possible, as well as a renewed, revalued perception of the environment and of the collective being itself, while reclaiming the dialogue between the city and its inhabitants, and opening up a fruitful field for new images, memories, and possible spheres for integration.

Finding creative ways that allowed true communication with the people was fundamental for Diego Barboza. His actions were aimed at establishing “a direct relationship between art and humankind,” as a way to combine art with life, and to encourage an unconditioned, connected, and liberating collective expression. These ideas would be in the germ of the poetics contained in the phrase “Art as people / people as art,” which the artist coined, years later, to synthesize his thoughts about participatory art. This is also directly linked to Oiticica’s vision, expressed in his statement “The museum is the world [and art] is the daily experience.”

Although Barboza never formally taught, he led educational events on several occasions, especially art workshops for children and young people, many of which unfolded within the framework of his actions. In England, his events were linked to artist training institutions. In 30 Girls with Nets, for example, students from the London College of Printing participated, and in Put a Net and Come Along, people were invited to make paintings and exhibit them at the London New Arts Lab, which was an alternative center for artistic counterculture. Back in Venezuela, through his wife, Doris Spencer, Barboza was linked to the public library network program established by the National Library. Many of his participatory art events were channeled through this program, which also offered several creativity workshops conducted by the artist. In them, Barboza did not act as a traditional teacher but rather as an entertainer who made real efforts to teach the free exercise of creativity. As with all art, there was really nothing to teach; the point was to provide tools to unlearn the stable ways of looking and making. To this end, the free expression of the participants was encouraged through painting and collage. In some workshops, they also created props and other elements that would be used in street actions.

It is worth noting that the ‘poetic actions’ carried out in Caracas after his return in 1973, increasingly integrated people's participation and a relationship with folkloric manifestations. Cachicamo Uno [Armadillo One], for example, held at the Ateneo de Caracas in 1974, was a party inspired by Oiticica's environmental installations, in which viewers were invited to use the five senses to interact with different elements of Venezuelan popular culture. In La Caja del cachicamo [Armadillo Box], Barboza used a wooden box from whose sides unfolded long strips of red cloth with the word Cachicamo written across them. The strips had bells attached and were carried by two dancing persons who moved around inviting people to dance too and join the event. Such ‘poetic actions’ were part of Barboza’s intention to reconnect people with their innate communicative capacity, which he envisioned as a spontaneous, authentic, festive, and, in a way, cathartic drive. Art was the way to relearn this authenticity of non-alienated expression and to experience the poetic dimension of living.

De la Escuela de Atenas a la Nueva Escuela de Caracas [From the School of Athens to the New School of Caracas] (1985) was the last participatory action carried out by Diego Barboza. For this occasion, he conveyed a group of artists that dressed in colorful tunics and slowly walked to the Galería de Arte Nacional in Caracas. There, they staged Rafael Sanzio’s fresco The School of Athens. By recreating this work, Barboza earned a place among the guiding figures of the generation of artists who contributed to laying the foundations that allowed, in our context, to open the doors to contemporary conceptions of the creative act.