Learning from the Outside

07/11/2022

In Colmenárez's work, breaking with the asymmetries of power relationships becomes a recurring sign. The artwork is an excuse for holding a dialogue, an event that will allow the individual to dissolve into the collective: there is communication and communion.

The participatory propositions that integrate the work of Asdrúbal Colmenárez (Trujillo, Venezuela, 1936) are the result of a will to transform and alter the learning processes, by unfolding participation and playfulness as an aesthetic experience and a creative praxis. In this way, the confluence of art and learning through the experience of play becomes a territory for deploying imagination, while emerging as a strategy for individual growth and the construction of a collective fabric weaved around the possibility of creating and experimenting from the participatory, through its ever-unfinished forms, the unexpected: what is yet to come (as future and utopian horizon): otherness and the other, what differs from its initial state: what becomes. That differing and diverse which is implied in the instant of creation, conceived of as a poetic state that reintegrates and conveys us to commune with realities.

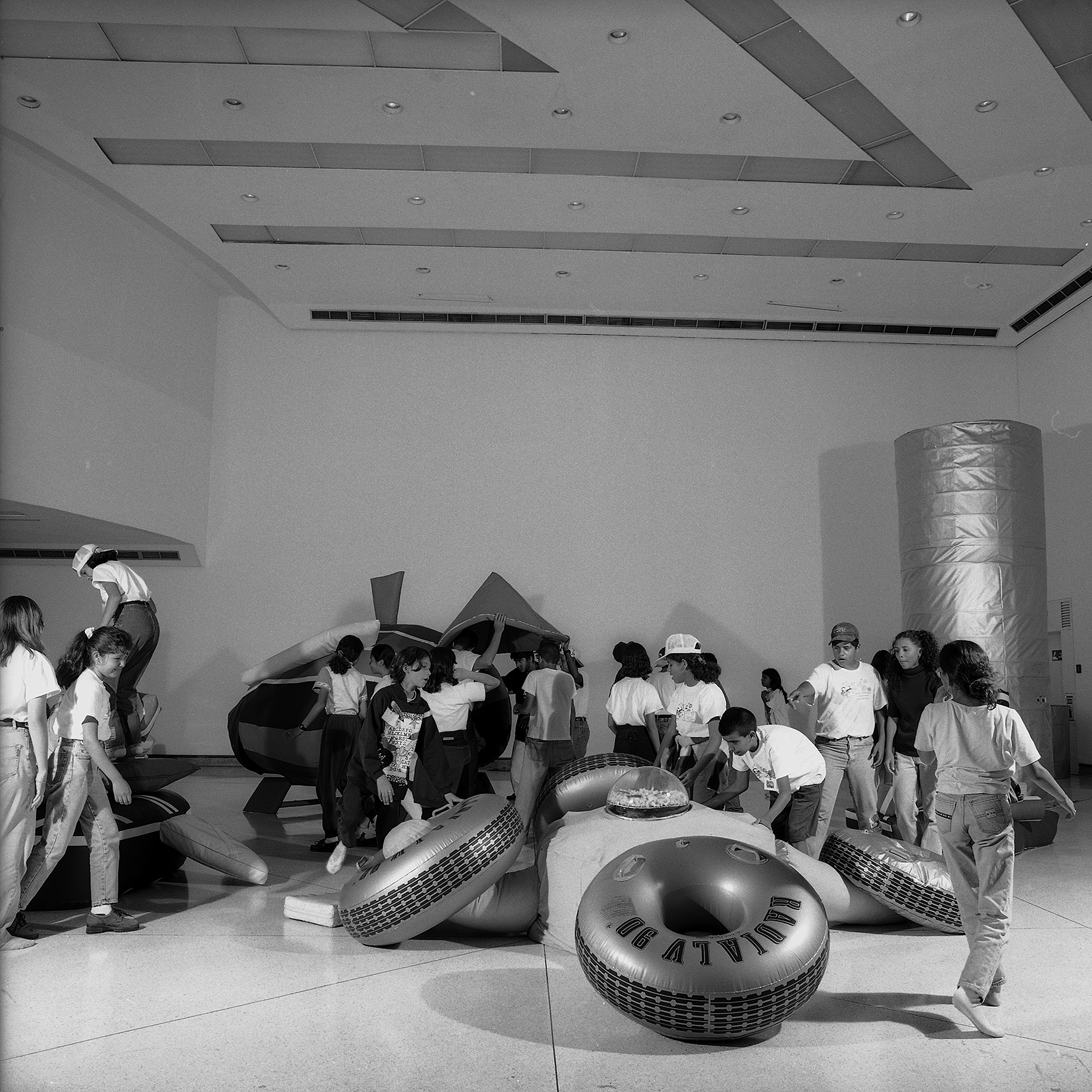

This view is key to the transformation of learning spaces, but also to overflowing the notions of art. Thus, the participatory propositions of Asdrúbal Colmenárez—the Psycho-magnetic Tactiles, the Polysensorial Alphabet, the Psychographiterre, the Psychorelatives, the Psychomechaniques, the Psychotactiles, or more recently: the game of billiards—together build an alternative for the permanent transformation of the experience and its participants.

Artistic practices and learning processes merge through the notion of play as an event of pleasure and amusement. A structure that has a few rules but its flexible nature erases and moves them, to transform and conceal them when the players find it necessary. Nobody wins, nobody loses, the pleasure of playing and diving into the unexpected merely moves around; that which is always a question and longing: the experience of creating at liberty. On the basis of this passing instant, which is of constant participation and communion, the human condition is revealed: being another and another thing, for also being ourselves.

Paris is the City (...)

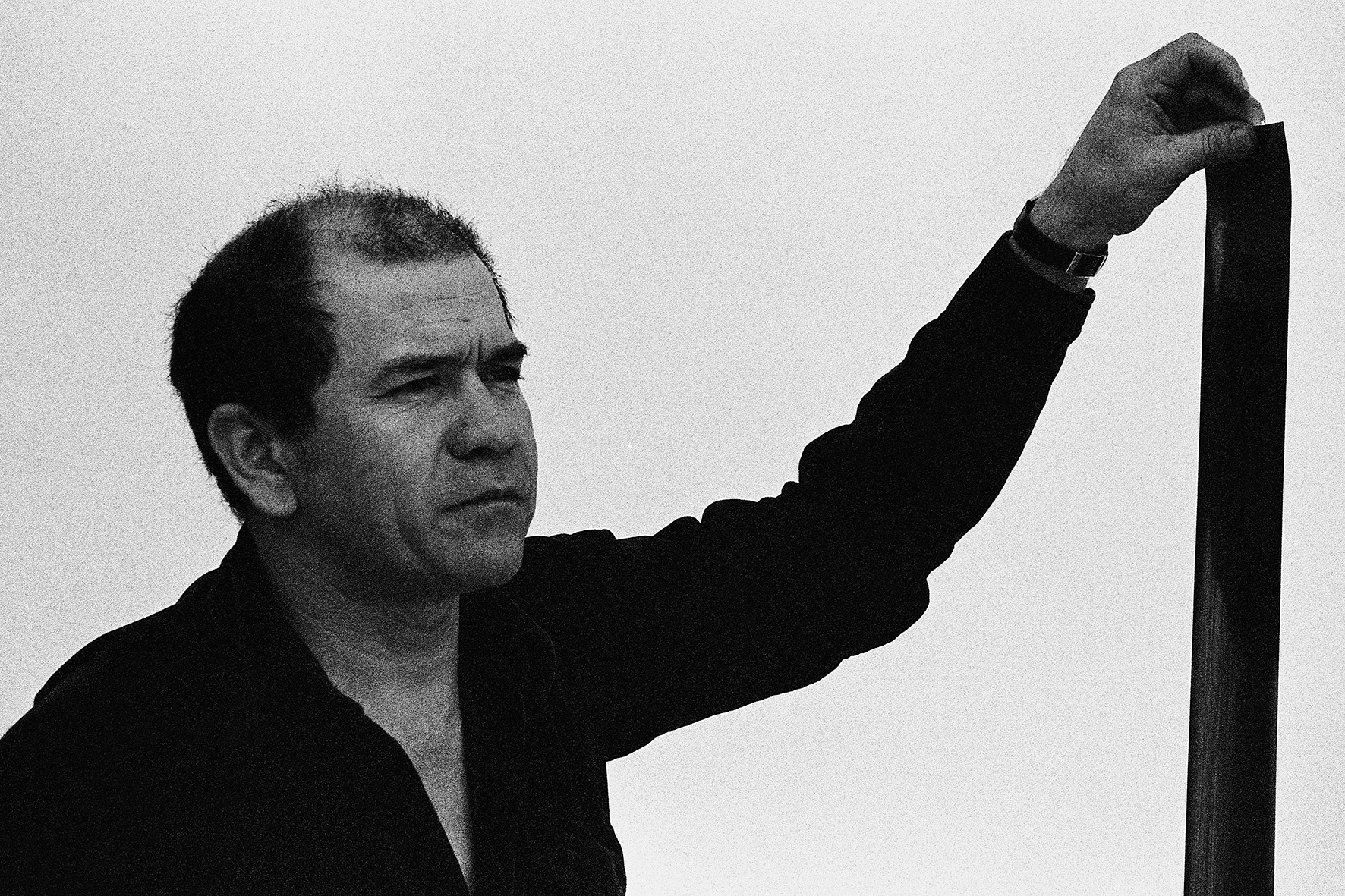

In his youth, Asdrúbal Colmenárez worked at his father's carpentry workshop in the city of Trujillo (Venezuela); he also spent time at baseball practices and was part of the team Deportivo Trujillo. So, early, perhaps intuitively, both the game and the production experience at the workshop played a significant role in his learning and creation processes.

There is also a constant evocation in Colmenárez's discourse of the creative qualities of popular traditions, for example: the manger installations for celebrating Christmas, the arbitrary scales of the objects that make it up; also in the creative use of farmer’s metaphors to describe natural phenomena.

In the early sixties, on the local radio of Trujillo city, Asdrúbal Colmenárez met the Chilean artist Dámaso Ogaz, a multifaceted artist, regarded as a pioneer of mail-art, who was to begin teaching art at the newly-created Museum of Contemporary Latin American Art (1961-1962). Immediately, a significant friendship started to grow between the two artists, which allowed for catalyzing the curiosity of the restless Colmenárez.

Dámaso Ogaz represents a reservoir of information for the early creative explorations of Asdrúbal Colmenárez. Through the conversations they have, he hears the names of abstract painters, such as: Antoni Tapiés, Willem De Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rotkho, among others, for the first time. But their dialogues are also loaded with literary references: Lautréamont, Baudelaire and Novalis, as well as reflections on dodecaphonic compositions.

After winning the Yomiuri Prize in Tokyo at the 2nd Young Artists of the Pacific International Exhibition (1962), Dámaso Ogaz moved to the city of Paris, from where he wrote a letter to Asdrúbal Colmenárez (perhaps an annunciation of his mail-art propositions?) and told him: "if you have a valid work, Paris is the city where it shoots up".

Under these premises, displayed as horizon and destiny, Asdrúbal Colmenárez travels to France. He embarks on an unprecedented journey, which takes him to Europe without even passing through the country’s capital, Caracas. Colmenárez makes a 12-day voyage aboard the ship "Americo Vespucio" and arrives in Marseille without mastering French, with little money in his pockets, and goes to Paris by train. He arrives in March 1968, weeks before the student revolts known as 'May of '68'; these events would become one of the fundamental experiences to incite a radical change in his artistic explorations.

Poetics of the Event

Asdrúbal Colmenárez arrived in Paris full of dreams, impulse and longing for change. It was certainly the spirit of an era that was starting to become critical and problematic on a global scale. The processes inaugurated in societies during the post-war period are multiple: a) the birth of the post-industrial society and its critical counter-narratives; b) the emergence of liberation movements in African and Middle-Eastern countries; c) the alternative thesis of the guerrilla hotspot embodied in the Cuban revolution; d) awareness of the ecological and environmental dilemmas inherent in traditional development models; e) the emergence of demands for spaces of freedom and cultural renewal; f) the impact of new communication technologies; and the most powerful of all, g) the new generations demanding, with the presence of their bodies on the streets, the end point of an era underpinned by totalitarian conceptions and repressive power regimes, to begin, in this way, the transforming emergence of new expressions and meanings for life.

Colmenárez himself recalls:

"when I arrived, in March, I could not imagine that I would witness the largest performance, 300 thousand people parading on the streets and singing the Marseillaise and the International (...) Like many of my generation, I had dreamed of the revolution, so I remember crying when I saw the demonstrations (...) The slogans in the streets were also part of a dream: Be realistic, ask for the impossible; forbidden to forbid; phrases like that, there were thousands of slogans that were made at the School of Fine Arts in Paris by students and teachers; within this context I reflected: If until now painting has been for seeing: why not make an art for feeling?"1

That context, the great participatory performance implied in the youth rebellion of May 68, marked the beginning of a search characterized by interpreting art as an event, as something that occurs. This perspective introduced Colmenárez to the studio of the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV), led by Julio Le Parc; he also learned about the propositions of the Japanese artists group Gutai, which reaffirmed his ideas about an art for feeling, for the senses, for perception and participation.

Soon, Asdrúbal Colmenárez began to experiment in his workshop with magnetic stripes that allowed him to develop the proposition that he called ‘psychomagnétiques’ (psycho-magnetics) and which he accompanied with a text as manifesto, where he outlined his critical horizon:

"[...] when I speak of current art, I’m thinking of an objective art which contains in itself its own reality; this living art cannot use words such as composition, forms, relationship, structures. As far as my psychomagnétiques are concerned, I prefer to speak of event, of modification, of transitionality, I propose sensory experiences that should motivate a situation different from what has been yesterday’s art, which still persists supported by some governments that prefer to immerse people in collective lethargy."2

The psychomagnétiques are works that the viewer can constantly modify and complete through their manipulation. In 1969, he was invited to participate with the psychomagnétiques in the show Atelier du Spectateur, under the gaze of the critic and researcher Frank Popper. The exhibition promoted the manifestation of a participatory art where experience became the dissolution of the spectator and artistic object dichotomies, which Popper described through the work of Colmenárez as a progression towards an authentic creativity that he defined as: "[...] the 'total' participation of the spectator, a participation of the senses and consciousness, is not impeded by the limitations imposed on them by codes and traditions in the general sense of the terms. What they propose to the viewer is the outcome of their own existential commitment and, to this extent, they incorporate real life elements into the artistic proposal.”3

Around these years, Asdrúbal Colmenárez met in Paris the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark. This exchange with her encouraged him to continue exploring the paths of concern that he had been insistently walking: an artistic practice for perception, an art that can be felt, oriented towards the contingent and transformative emergence of the experience, the outcome of an never-ending instant of existence that turns into the act and impulse to create. An artistic practice far from the pretensions of the market, far from the very idea of a work of art. Therefore, unfolding as a sensitive experience: art as events, a trait that represents one of the essential cores of Asdrúbal Colmenárez’s body of work.

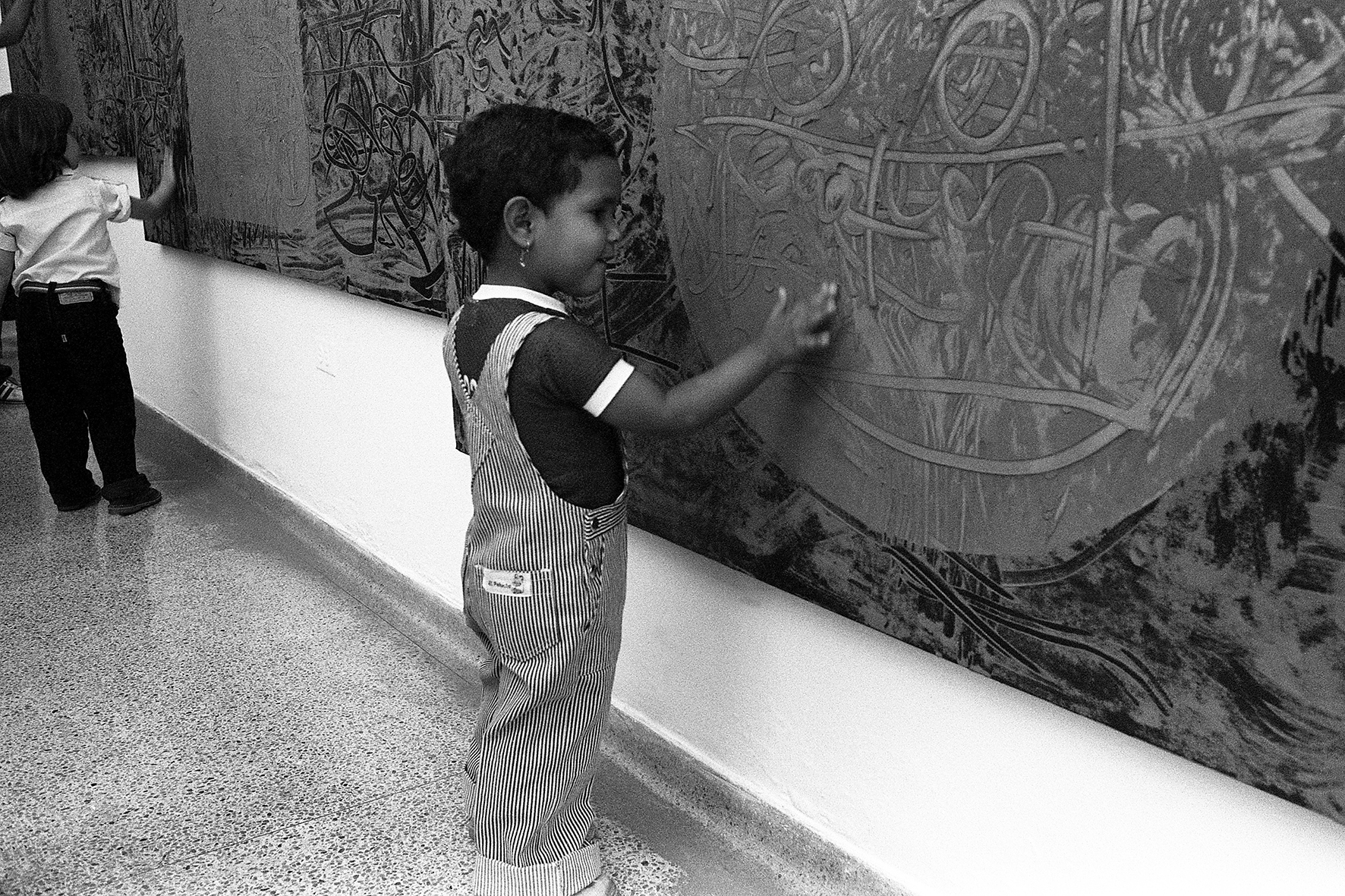

In 1971, he began to conceive the Alphabet Polysensoriel. He completed the project in 1978, thanks to being awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship, and presented the results at the Musée des Enfants du Musée d'Art Moderne in the city of Paris. The Alphabet Polysensoriel was exhibited in Venezuela for the first time in 1980, at the Galería de Arte Nacional in Caracas, along with other propositions conceived for the development of writing. Regarding this exhibition, Colmenárez explains: "(...) I conceived of the idea of a polysensorial alphabet that had as its guiding principles the non-inhibition of the creative abilities at the time of learning to read (as is commonly noticed), of bringing children coming from different sociocultural environments into the same plane of equality, and of eliminating the knowledgeable power of the teacher."4

In Colmenárez's work, breaking with the asymmetries of power relationships becomes a recurring sign. The artwork is an excuse for holding a dialogue, an event that will allow the individual to dissolve into the collective: there is communication and communion. They are works that generate ideas through perceptive stimuli, embodied in the spontaneity and gesturality of the creative act as a way of unleashing human potentialities. Playing without rules, playing for pleasure. Creating at liberty for encouraging what occurs as an alternative and a possibility. Throwing the ball: existing like a river or the planets: in act, in movement, in rhythm, but above all, in freedom.

The notion of play allows to produce an active and critical intersubjectivity. As Victor Turner argues,5 it involves the formation of a liminal space, a threshold between real life and the imaginary, the everyday and the unconventional: fantasy. The liminal power contained in play represents a powerful tool for fostering thinking that favors creativity and learning from perception. For Asdrúbal Colmenárez, that is: "to the extent that one manages to exercise the right to create in freedom, the endless possibilities of the human being."6

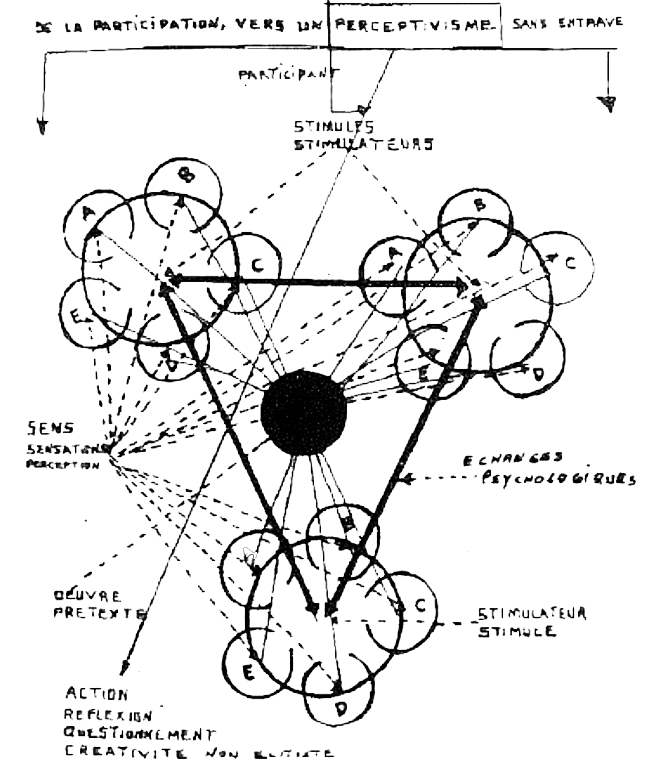

From Participation, towards Unimpeded Perceptivism

In Frank Popper's book Art, Action and Participation, Asdrúbal Colmenárez outlines a diagram where he unfolds his ideas around participation, defining it as: De la Participation, vers un perceptivisme sans entrave (From participation, towards unimpeded perceptivism). In it, he settles the notion of the "artwork as a pretext," understanding it as a device that functions in the way of a sensorial stimulator (touch, sight, smell, hearing, taste) to create in the participant a tension of sensations, perceptions and meanings, encompassed under the concept of 'perceptivisme' (perceptivism) as a space of individual stimuli that, simultaneously, fosters collective interaction, through a psychodynamic exchange that leads the subject into a space of what he calls total creativity.

In Asdrúbal Colmenárez's own words, it is about "the act of perceiving that we can interpret as feeling with awareness.” A perception where thought and action converge and which allows the emergence of Self-awareness (identity) in active and intersubjective relationship with the other (difference) and which opens the possibilities towards otherness (creation).

This process creates a complex learning space, a chain of propositions and actions that make up an awareness of being propelled through processes that are inherent to art as dynamic fabrics rooted in perceptual experiences. This implies the emergence of certain considerations in the subjects: of aesthetic, ethical, and philosophical (ontological) nature, from the notion of the work of art as a pretext and starting point for the unfolding of the human, art as a way for the awareness of being—as Asdrúbal himself defines it when re-interpreting the idea of perceptivism.8

In relation to this properly ontological dimension, Colmenárez comments:

"Then, just as the philosopher Descartes affirmed: 'I think, therefore I exist,' as I am a primitive, I would say: 'I exist because I perceive'; in a nutshell: before thinking, we perceive. I like to place the senses as a process prior to thought. Everything we feel goes to the brain. Our mind conceptualizes whether something is far or near, whether it is hot or cold; whether it is sweet or bitter, sharp or deep, pleasant or nauseating, thanks to perception. So, the brain sends us these meanings based on the information that the senses manage to perceive. That is why I affirm that beauty is not the most important thing when conceiving a work of art; the important thing is that the work can lead us to a reflection: philosophical, psychological, social, political, anthropological or ecological."9

Learning from the Outside

The complex nature of the processes involved in the idea of "participation, towards unimpeded perceptivism" for encouraging the space of total creativity proposed by Colmenárez, implies that the learning processes involved are also complex in nature. In this sense, the participatory/sensory/playful propositions that make up Asdrúbal Colmenárez’s body of work (1969-2021) present an activating element in the various conditions that lead to a learning situation. In this way, the participatory dynamic that unfolds activates a link in the complex chain of learning. Thus, we could suggest that its purpose is focused on: "awakening the latent faculties in each of us, which are gradually numbed as traditional teaching at school, the university and work, introduces us into automatizing mechanics that condition creativity."10

In the context of these ideas about art and learning, Asdrúbal Colmenárez points out:

"Nature is perhaps our great source of knowledge. We learn from all the things that surround us."11 He concludes that: "Finally, we human beings are nothing but a latent magma awaiting a musical melody. Perhaps we would have to create new words that no one would understand to describe the complexity of learning and life (...) Every minute of existence teaches us that we are producing concepts that come together with other concepts that come from other cultures and other thought systems. Then, it becomes clear that we as human beings have a need for establishing bonds among us, to bond with each other, for living in a complex world. We simply cannot understand everything. But we can, indeed, feel a lot. The things we think we know or understand no longer exist in us. So, we must foster a learning that goes beyond ourselves."

Based on these arguments, we could suggest that Asdrúbal Colmenárez intends to lead our senses towards the experience of the world, a way through that moves us outwards: projecting our senses towards the environment to turn each act into an opportunity for learning, conceived on relational dynamics and constituted as a process that goes—in his words—beyond ourselves. This perspective turns out to be a key aspect of his work: the emergence of an event where the individual is transformed into collective polyphony. Let us remember the power of the imagination unleashed in the revolts of the French May of 1968, which welcomed Colmenárez to Paris and the image of students and professors overflowing the streets with words and gestures to evoke the urgency of new realities.

So, we are talking about a learning from the outside: conceived towards nature, towards society, towards history, towards the cosmos, towards the other and otherness. A poetic learning, open to chance, imagined in symbolic exchange and communion between words and perceptions; mind and body entwined in a collective celebration. A learning that goes beyond us, for shaping the unprecedented landscape that we are, that we inhabit, and which, in time, complements and conforms us.