Villanueva the Architect, the Teacher, and the Teaching Notes

07/11/2023

by Maciá Pintó

If the Ciudad Universitaria and the Faculty of Architecture can be considered true classes of urban planning and architecture from which to draw lessons, the "Teaching Notes" open a door to a new reading of Villanueva and his work. [...] They represent a valuable pedagogical instrument because of their content, philosophical reflection, ethical purpose, and practical interest, more related to learning, to the purposes and methods that converge in teaching.

Carlos Raúl Villanueva was born in the twentieth century, on May 30, 1900, in the Venezuelan consulate in London, but his childhood and adolescence were spent in France, where he attended high school at the Lycée Condorcet, with a formation marked by the Cartesian rationalism that prevailed in the institutions of learning; he then entered the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris and graduated as an architect. Thus, reason and academia form an order, principles, and thoughts, and values that will allow him to face the problems and tasks of the profession with wisdom and sensitivity. Knowing how to see and feel, sharing teamwork, being attentive to change, and being willing to explore the new paths opened up by the manifestos and postulates dictated by the modern avant-garde in art and architecture, will ultimately be the common denominator that will mark his life and his work: Villanueva's inalienable and fruitful relationship with the art and artists of his time. The exemplary realization of the "Synthesis of the Arts," invoked and desired in Europe, was achieved in the University City of Caracas, Venezuela, where Villanueva was both architect and teacher.

Thinking and realizing: the Architect

“Villanueva, the Architect” was the customary way of naming himself, marking his books, of signing or saying goodbye in his personal correspondence. It is the most decisive manifestation of the impossibility of separating Villanueva the man from his condition as an architect; a sign of both acceptance and a certain pride; also, a clear expression of his particular humor and frank irony.

With age and experience, his friends, students and professors, fellow architects and collaborators, affectionately called him "Maestro Villanueva," not only because of his human condition or as a teacher and guide of continuous cohorts of professionals, but also in recognition of the value and importance of his work, within the framework of those architects called "Masters of Modernity," within the Latin American and world context; as was recognized by some critics and publications at the time. His teaching transcends the limits of the classroom and the design workshop, of his writings and lectures. It is his projected and built work that definitively marks the singular value of his achievements.

However, for those who knew him, it is perhaps his affable and generous disposition, his example, a symbol of righteousness and probity, his closeness and experience that, in the end, is the most important reason for him to be affectionately recognized as a Maestro. Two ways of naming him, two paths that run parallel and on a par with that institution so near and dear to him, the Central University of Venezuela, and the creation and operation of the School of Architecture and Urbanism. In fact, the project and construction of the Ciudad Universitaria [University City] of Caracas, designed by Villanueva himself, took place at the same time as the architectural studies took shape. In 1944 he began the construction of the Ciudad Universitaria, and that same year he became a professor of Architectural History; courses taught in the classroom that would later be expanded to include urban planning. Likewise, the courses in Architectural Composition, with the training in projects carried out in the Workshops, of academic inspiration, directed by a relevant figure as in the Héraud Workshop, where he completed his studies in Paris. In this case, the guidance of the Villanueva Workshop is under his direction, bringing together an important group of outstanding professors and students, some of whom went on to become professors, consolidating an earned prestige and a long trajectory in the training of the best professionals in the country, who, while preserving the affection and relationship of belonging, did not manage to form a school, in the sense of following or repeating his architecture.

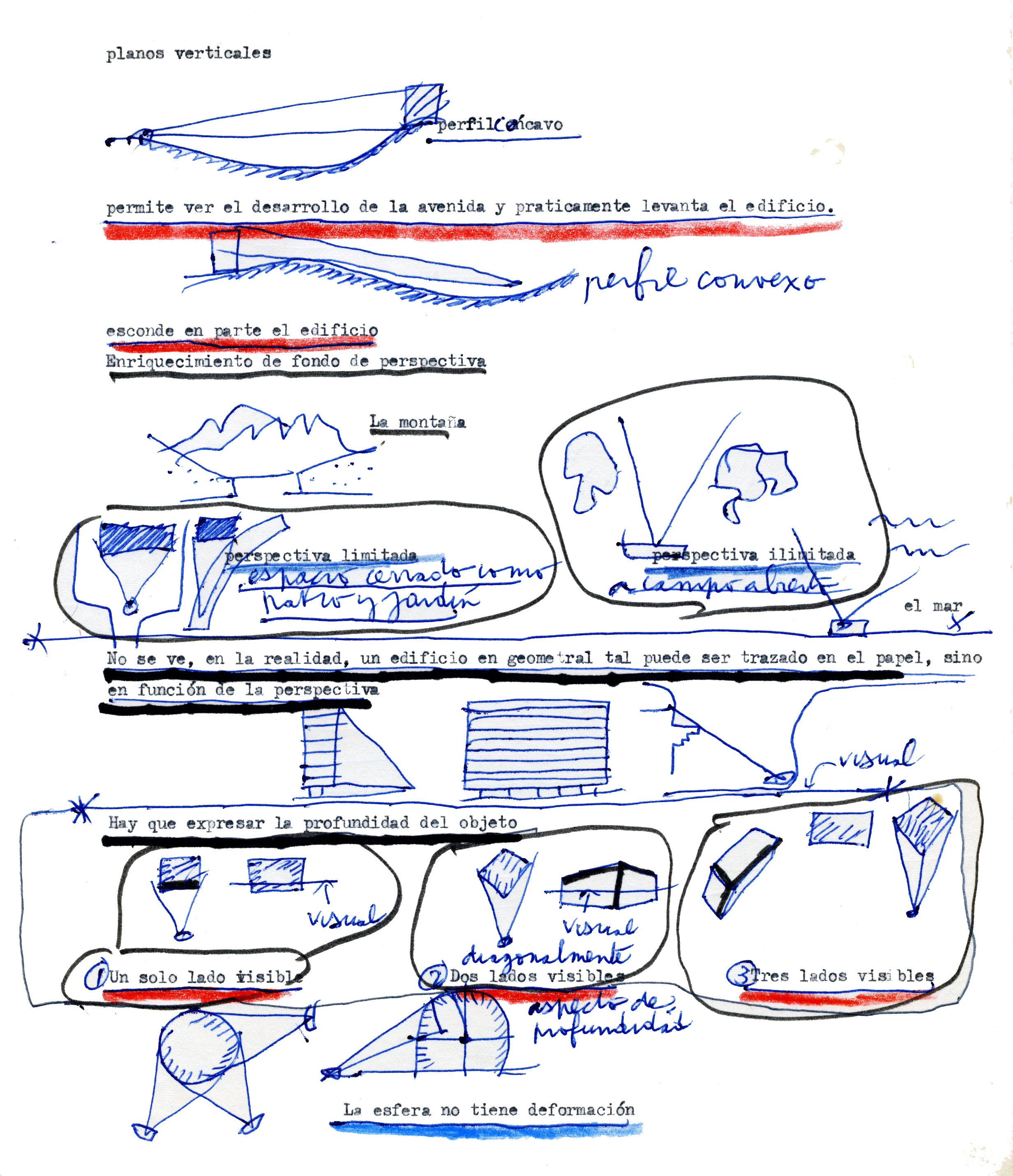

Villanueva, together with a small group of architects, formed the initial faculty that started the School of Architecture. For many years, he participated with his presence and guidance in its development, without assuming any managerial position, although he did hold various positions in academic administration: Head of Chair, Workshop, and Department. His teaching activity is centered on History and Urbanism courses, for which he prepared countless notes with texts and drawings that he reproduced on the blackboard, using colored chalk, or projecting slides of a vast repertoire of world architecture, which he treasured and classified in metal boxes and other long wooden boxes, in turn, marked and identified according to their use. These slides were also key in the oral exams of his history courses, in which the student had to randomly select an image and based on it develop the speech of his test. For the final papers, he requested texts and drawings, in the development of an analytical study of a work of architecture. Architecture and the city define the contents of his programs, theory, and history, the basis of his reflections.

The Teaching Notes: the Maestro

Villanueva participates and accompanies in a decisive way the evolution of the Faculty, up to the process of "university renovation" promoted by the students and the resumption of activities in 1970. However, if we want to know his ideas on teaching and architecture, we must refer to the "Teaching Notes": hundreds of loose pages, gathered in folders with variable and changing indications regarding the themes and contents they deal with. They constitute an enormous amount of support material for his classes, written on letter-format paper, typewritten, with handwritten texts, underlined and crossed out, together with a profusion of drawings and diagrams, where he records his thinking and training. What we have called "Teaching Notes" are a valuable, original, and peculiar material, which defines very well Villanueva's idiosyncrasy as a systematic, orderly, and studious person in the subject of his interest: architecture and the plastic arts. They represent a valuable pedagogical instrument because of their content, philosophical reflection, ethical purpose, and practical interest, more related to learning, to the purposes and methods that converge in teaching. They are made only for himself, as a study and memory aid for his classes, as they are very personal; intervened by critical reading and periodic updating, the changes in perspective, and the evolution of the courses.

The "Teaching Notes" open a door to a new reading of Villanueva and his work. If the Ciudad Universitaria and the Faculty of Architecture can be considered true classes of urban planning and architecture from which to draw lessons, it is no less true that we can approach his dimension as a teacher from a more private and intimate reading of these texts and drawings, because although they also reproduce fragments and interlaced quotes from various sources and authors, it is their particular articulation that gives them meaning in the context of a theme or aspect that is studied and repeated, constructing lines of reading and points of view that are maintained, be they classes of history or urban planning. And if they were originally ordered by him in different folders marked and, in turn, remarked with different titles and underlined, the notes were interchanged and mixed by the circumstances of the programs, the classes, and his own concerns and explorations, until they lost their relative "order" over time; this led to group them from their titles and general contents, in five themes: teaching, architecture, history, city, and urbanism.

And if they were originally ordered by him in different folders marked and, in turn, remarked with different titles and underlined, the notes were interchanged and mixed by the circumstances of the programs, the classes, and his own concerns and explorations, until they lost their relative "order" over time; this led to group them from their titles and general contents, in five themes: teaching, architecture, history, city, and urbanism.

Villanueva left us few written texts, except those written for some book or magazine, conference, or congress; likewise, very few original sketches and drawings of projects have been preserved, hence the importance of these notes as unpublished material in which to search for the ideas and principles that support his architectural work. They are a faithful record, memory, and document of his vision and thought; the keys to a possible critical interpretation. In his notes, Villanueva rightly affirms that "architecture is also studied," and these pages, revised on repeated occasions, are the most irrefutable proof of his constant spirit of research, a guarantee of the permanent teaching-learning process he himself followed in a clear and consistent manner throughout his life.

Looking more closely, the notes were written for himself, as an intimate diary, only for personal reading and reflection; this is a way of dialoguing with thought, writing short phrases and sentences that function as keys to open up to a larger field of ideas to be developed in the classes. They are designed to rationalize and systematize the themes and approaches of a syllabus. They are, in turn, a mnemonic resource—the ideal means to study and memorize knowledge—the way to review and prepare the classes, by being rewritten and reread, crossing out and underlining, over and over again, to discard or highlight what is considered pertinent.

Although guides and divisions of spatial and temporal order always appear, we can affirm that his vision is basically synchronic; for although he highlights the known historical periods—medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, and others—or distinguishes the different locations—European or American, the variety of cultures and countries—neither his understanding of history is "chronological," nor that of urbanism is "geographic." In their approach the "practical" purpose of theory prevails, applied to history and criticism, emphasizing technical and aesthetic valorization. In short, they are, or can be understood as a "synthesis," the sum of a thought, a life, and work.

Studying the architecture of words is part of our learning. Thinking, writing and reading are three terms and actions that allow us to better delimit the particular relationship we establish with architecture and its teaching. Villanueva insistently reminds us that the architect must remain, by definition, an intellectual. Practice, theory, and criticism converge in the sphere of thought; to project in the head, to cultivate ideas, and to strengthen intelligence, were maxims that he enunciated as primary qualities of the architect.

The space of the page also has its own architecture ready to be seen. The reading of these notes makes sense to the extent that we can give life to Villanueva's ideas, trying to establish a parallel with his work, by discovering and recognizing the values present in the constructed fact. Having the commitment, as readers, to open different paths of interpretation, which go through the necessary reflection on their role in the teaching-learning process. Maintaining that ideas are confronted, changed, and reaffirmed in a critical way, led Villanueva to always recommend to students that "they should learn to see their work through the eyes of others."

Curiously, he was emphatic in affirming that paper is the architect's worst enemy and that architecture is not a matter of drawing, since drawing is a support for thought. Drawing expresses a thought: to trace through the gesture of the hand and the guide of the eye is to enunciate an idea. Many of the drawings in the teaching notes are taken from images and photographs, from projects and works referred to in various texts, others from his direct experience with architecture; but in any case, they are formulated as conceptual syntheses, through clear and simple schematic, evocative and suggestive strokes.

We can follow in Villanueva's readings his interests, preferences, and opinions, as we go through his library and review different materials, and recognize by means of underlining, exclamation points, asterisks, calls, and notes, that seem relevant to him and which he sometimes copies and reproduces when sharing a point of view or supporting his own convictions. To follow the evolution of the different courses of History and Urbanism, Theory and Criticism, is an arduous task; likewise, to review the content of the different programs. In fact, the real content of his courses is in the "Teaching Notes," and it is precisely teaching that Villanueva addresses with the greatest passion and clarity, and he repeatedly insists on maintaining the integral formation of the architect, humanistic, philosophical, technical, and artistic. He believes that learning should not be based only on the acquisition of knowledge, for he prefers "a well-made head to a well-filled one." He repeats to his students the principles he applied to himself, insisting that everyone should take responsibility for their own education through study, reflection, debate, and criticism. Exploration and change, creation and synthesis are the guides of his life and work.

Synthesis of life and work: Architecture

This enriching and suggestive itinerary allows us to travel through all those past and present works, which without being his own, he makes his own, placing them in the context of his words and giving them a new materiality through the line that shapes the gaze. To recreate the works present in the history of architecture in the face of teaching is, in turn, to think of himself as the architect of a work that synthesizes and expresses his vital circumstance, in a century that harbored the dream of modernity. In his notes, Villanueva never speaks of his work, nor does he refer to it as an example; however, although it may seem paradoxical, we can affirm that, in essence, he speaks of nothing else. He maintains the constant process of learning, because according to him "architecture never lies."

In the Design Workshop, or Project Workshop, as a professor of what used to be called Architectural Composition, Villanueva focuses his attention on the process of ideation, the sum of creative work, considering two moments: analysis and synthesis. He distinguishes the "cold" moment of analysis together with intuition, to study the problem and recognize the context, from the "warm" moment of creation, which requires imagination and talent. The actions of observing, perceiving, ordering, and providing, are at the basis of this drawing that he repeats in the notes, of the "eye" that looks and measures. The Workshop brings together the best of the Master's teaching and guidance, summons his project practice and his refined critical eye, in a close and accurate dialogue, sometimes devastating for the unprepared student. For, when faced with a "plant" of a project, the question of where the "north" is, together with the conditions of the context and the orientation, could not be absent. Equally, the value of the measure, the scale, and the adequate proportion of the spaces was registered by him immediately and with uneasiness, and tell the student as criticism: "you have a square eye." He asks to have a vision that is beyond the scope of architecture, understanding it as a social, historical, and culturally engaged profession. For him, the first responsibility of the teacher is: "to form the student's head." To stimulate the action of thinking, together with a careful visual education. To know how to read, to know how to see, and to recognize the right measure of things. Measure that is "measurement"—beauty and proportion—and "restraint"—virtue, moderation and restraint. He emphasizes his firm conviction in the social function of the architect and the architecture he creates: the construction of the stage for the life of man. The call to assume a commitment.

Villanueva was a man of few words, he recognized himself as a man of action. He was a doer. His works are open books of his architectural ideology. Le Corbusier used to say that it was necessary to "learn in direct contact with the works in execution," Villanueva is the clearest example of this sentence; at the Ciudad Universitaria, he shared his daily project work with his presence at the construction sites and classes.

The School of Architecture is a paradigm of this teaching-learning process, which summarizes everything done at the university and which also extends over time because as a school it is a building that teaches. This building was his work, also his home, where he worked as an architect and also as a teacher, enhancing its educational dimension; sometimes strong and clear in the face of criticism, quoting Bruno Zevi's sentence: the school "has not been conceived in terms of passive education, but as a building that attracts and allows active experimentation precisely in the environment in which teaching takes place."

Teaching and architecture are at the center of his reflections, together with the architect and composition, as well as the persistence of a trinity: function, form, and space. In Villanueva, man and work cannot be dissociated; likewise, his facet as a builder and his ethical reference are examples of a life dedicated to work and to the public function of architecture. The architectural space he conceives and builds is an expression of this vital and creative cycle shared by life and work. This recurrent process of thinking, designing, building, and experiencing a space is continuous, prolonged, and repeated for years, in a work such as the Ciudad Universitaria; overlapping the different cycles with the presence and continued use of the same spaces, including the building of the Faculty of Architecture, his second home, a work that brings together and synthesizes everything done at the university, and is a lesson in good architecture. Throughout this enriching and unusual process, Villanueva learned from himself. His highly valued "synthesis" is the origin and final point of this convergence that brings together teaching and learning; a synthesis that is a value consubstantial to his work, for being his most refined project tool and the most faithful expression of his life.