How to Be a Chorus: Toward a Community-Building Theater

11/10/2023

by Artur Kon

Leia este artigo em português aqui.

It is impossible not to talk about the greatest artist that Brazilian theater has ever known.

Because José Celso Martinez Corrêa was much more than just an artist: he was and he is a group, a crowd, a chorus. He always practiced “the beauty of collective life” (according to anthropologist Jean Tible1) and this way he taught us to leave, at least sometimes, the solitude of the individual spectator and enter the collective scene-feast.

I dedicate this text to him, who left us while I was writing it, but who will continue to be our guide–because, as José Miguel Wisnik said, “there is no death that can end with him.”2

And I take the opportunity to share the feeling of philosopher Douglas Rodrigues Barros: “Today, with a theater that is increasingly individualistic, it is difficult not to feel like an orphan with his death.”3

In the delicate Brazilian political moment, our theater–once characterized by the abundance of groups working in collaborative processes, in different ways rediscovered by each collective and each creation–seems rather dominated by solos and individual works (even from many artists who performed or still perform in companies that were part of the rich previous period)4.

It is not possible to explain this individualizing tendency by only one reason, but it seems relevant to mention some factors that may be at its origin. First of all, it is important to consider material aspects, such as the precarious production conditions (which makes it difficult for groups to meet during the time needed for a creative process), as well as reduced budgets for festivals and tours (meaning that only the least expensive works are selected).

But there is still the role of a social feeling among the artists (the growing difficulty of dialogue, but also the centrality of the urgent question of the “place of speech” and new protagonisms) and simultaneously, there are ideological forces that are difficult to ignore completely (the rise of a narcissistic individualism, in a “subjective turn” widespread by social media, transforming everyone’s life into a “Me show”)5.

The listed factors are not inevitable tendencies of an abstract capitalism, but all of them are part of a concrete historical process that had some important milestones in the last ten years in Brazil: from the “June Days” of 2013, through the parliamentary coup of 2016,6 the election of neo-fascist Jair Bolsonaro and arriving to his defeat in 2022, taking Lula back to the presidency.

These events caused, at the same time, political destruction–that generated the dismantling of public policies for Culture, as well as the undoing of social ties that were already weak in a republic on the outskirt of capitalism–and the difficult but necessary opposition to it (we cannot forget that this period begins with demonstrations that shouldn't be reduced to their fascist drift, although it must also be considered).

It is this opposing force that allowed, also in the theater field, in performance practices and in a broader sense, in arts in general, certain collective insistences that kept me busy–both as an artist and as a researcher–in this decade, and that I will try to map here. Not with the intention of attacking or undermining in any way the many important solo works that this period produced, but to try to expand the possibilities of our vision and our action.

The Strength of the Crowd

When the demonstrations of 2013 started, I was, along with the Cia de Teatro Acidental–a collective where I have worked for seventeen years–in the middle of a creative process. The play premiered more than a year later, in December 2014, and was strongly influenced by the country's political direction, which at that time we could only glimpse stretching our dystopian imagination to its maximum. The title expressed the feeling of anxiety about the future: O que você realmente está fazendo é esperar o acidente acontecer [What you are really doing is waiting for the accident to happen].7

At a long table, seven actors stage what at first appears to be an academic debate about the work O beijo no asfalto [The kiss on the asphalt], by Nelson Rodrigues–a playwright who, symptomatically, represents at the same time the beginning of Brazilian modernist theater and also the deepest reactionarism ever imagined (an idol for most of the right-wing until today). Little by little, the plot (in which a kiss between two men, as a gesture of mercy at the deathbed, is turned by the press and police into a scandal that destroys the main character) begins to contaminate the scene, and a rational argument gives space to a violent hate speech.

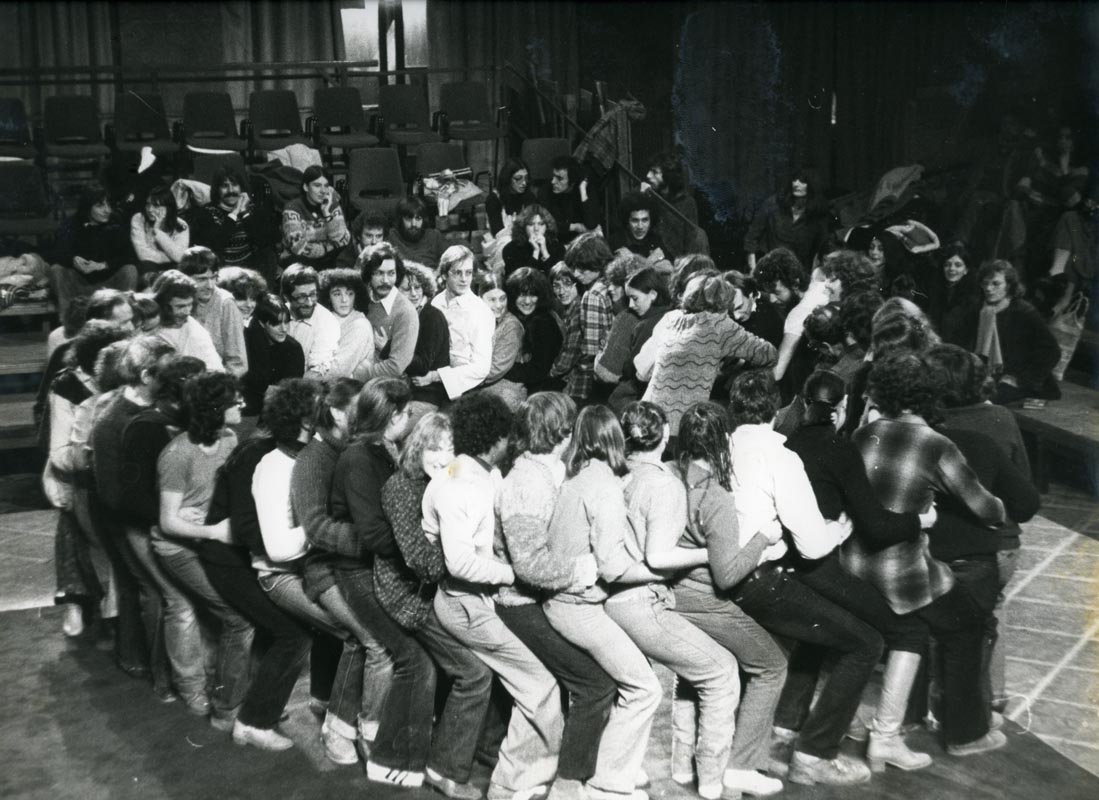

This does not happen, however, through dramatic dialogues between recognizable characters, but in a choral speech that, without clear distinctions between its members, directs the talk to the audience. With this, the scene materializes a bit of the mass effect from different historical incarnations of fascism, and which made conservatism appear to us, at that moment, as a threatening wave, almost impossible to stop.8

We found something similar in the performance Massa ré [Reverse mass], created two years later, in 2016, by Elilson, a young artist from Recife: “A group of Brazilians, wearing white t-shirts with the dates 2016 (front) and 1964 (back) in black, walk slowly, silently and backwards through the city streets with hands flat down. The start and ending points of the walk are pre-established in accordance with historical facts.”9 Here, the crowd leaves the stage, where there is still a representational layer that gives the artists some security regarding possible readings, and opens up to the uncertainty of its reception in the public space, where it may come into consonance or conflict with different political communities. The creator himself questions whether this action “can arouse support or agreement for a coup d’état” (that in fact was taking place that year), a question that “did not seem necessarily negative to me.”10

The artist's question is one that we also consider at Acidental: is it possible to reduce group movements to an expression of Evil11, and on top of that, an evil that is clearly different from ourselves: the fascist group that we, the good guys, oppose? Isn't that exactly what the ideology of neoliberal individualism wants us to believe?

It is this ambiguity that visual artist Cinthia Marcelle and filmmaker Tiago Mata Machado, from Belo Horizonte, seem to deal with in the video series Divina violência [Divine violence]. In Comunidade [Community] (2007), we see a line of people who are apparently waiting to enter some event, but suddenly they begin to fight, leaving the organized formation and creating a chaotic movement. In O século [The century] (2011), several objects are thrown from outside the camera frame, always on the same side, falling onto the street, as if they were thrown against some invisible (and perhaps unattainable) enemy. Finally, in Rua de mão única [One-way street] (2013), we witness a coming and going of protesters whose covered faces, in addition to several signs coming from outside the frame (especially a light suggesting fire and a lot of smoke), indicate that it is not a peaceful protest. In all three cases, we see the scenes from above, so the result is much more of a collective choreography than individual narratives, which end up almost erased. The violent and mass character of this collective, however, does not seem easily reducible to fascist tendencies, but also pulsates precisely in what resists them.12

Discovering the Neighborhood

In the search to better understand this ambiguity and leave the comfort zone of those who accuse the fascist movement from outside, Cia de Teatro Acidental began in 2016, to investigate fear as a founding political affection of our society, originating the hatred discussed in the previous play and a common denominator on the right-wing (which always seems to fear violence coming from the poor, black people and other excluded people) and the left (which, at that time, feared the rise of the extreme right), making us to shut ourselves up in gated communities with our similars, leaving those we understand as Others on the other side of the walls.13 The result of this research, E o que fizemos foi ficar lá ou algo assim [And what we did was stay there or something], premiered in January 2019, in the first month of the Bolsonaro government. There, a condominium meeting–where the presence of uncomfortable “strangers” emerged as a central problem to be discussed–turned gradually into a zombie movie, revealing the fragility of social ties and, at the same time, their paranoid nature.

Also in the play Os pálidos [The pale ones], premiered in 2015 by CiaSenhas from Curitiba, there is an end-of-feas situation–the characters “of a bourgeoisie trapped in itself, trapped by consumption and hoarse from protesting on social media”, all seem drunk, or dazed for some other reason, suggesting “states of inertia, paralysis and anesthesia”14–and the focus is on a certain decadence and strangeness.15 But the theme of cohabitation manifests itself here in a site-specific and relational scene: we are invited to enter the space of a house, split into two different environments (“suggesting all kinds of divisions”, says the group), where we will see closely these people, they begin the play waving pathetic little white flags before our eyes (a peace request?) and saying that “We are not who we appear to be, we are much more than that.”

The proposed (and at the same time questioned) complicity, challenges the viewer to question their own identifications and beliefs: “We are incredible, cultured, friendly, clean, snobbish, coward, perverted, aren’t we?” This is, as critic and researcher Luciana Romagnolli says,16 "explicitly manipulating our weaknesses” and “establishing an experience field that allows questions such as: What do we have in common? What brings us together or why do we unite?”

The Need to Regroup

This centripetal movement was further radicalized in E se a porta cair seguiremos sentados apenas mais visíveis [And if the door falls down we will continue sitting, just more visible], which premiered and completed its season at the end of 2022 (just in the final moments of the presidential elections). This time, however, instead of looking for what was similar between right and left (in a certain middle-class context), we researched what was specific to our field, based on a clash with the tradition of political theater embodied in the figure of Bertolt Brecht and his play (choral) A decisão [The decision]. In this work, as controversial as it is already canonical, a Party chorus investigated and celebrated the conditions for the victory of the Revolution (specially the overcoming–not without some cruelty–of naive and subjectively leftist positions, rather moral than political), on the other hand, our play reflected on failure, the absence of any perspective of radical transformation of society, and the reduction of leftist opinion to plain guilty moralism.17

We were also interested in the theory and practice of the “learning piece” (Lehrstück), understood not as a proselytizing theater, but instead, as an open process of collective study, a theater without rehearsal and without an audience, made from dramaturgy, but without having to limit itself to it. From there, emerge a series of proposals for interaction and audience inclusion established on scene (but always based on the idea that this relationship could not be successful, affirmative, but always precarious and questioned), as well as the invitation for Maria Tendlau, an expert on the subject, to direct the play.18

This collective insight is also the drive of the play Nós [Us/Knots], which Grupo Galpão premiered in 2016 in Belo Horizonte. The structure is simple: “Seven people get together for one last supper and, while preparing it, they expose their anxieties, fears, feelings, experiences, external pressure elements, which have a direct impact on the relationship between them,” that is, in the sometimes “conflictive relationships between the actors” that point “to the complexity of their trajectories (knots) in a collective practice.”19 The focus here seems to be on the structure of Brazilian group theater, with its struggles, shortcomings, but also its hopeful persistence.

Patrick Pessoa proposes “thinking of the play as a group therapy session (...)–in this case, of the subject called Grupo Galpão,” which could be considered a “theater archegroup” in the Brazilian context–in an “attempt to recover what was there at the beginning,” what makes us come together to create collectively.20 But, if the show is less explicitly political than Acidental's, it doesn't leave this dimension aside: its scenes “start from micropolitical gestures to project Brazilian macropolitics, when it articulates and is supported by the close bond that is established between that universe apparently private and the emergencies outside.”21

In both cases, it is “less about unifying groups than about learning to mend the patches of a fractured society, using the left as a laboratory,” as the thinkers Edimilson Paraná and Gabriel Tupinambá (2022) proposed.22 Because “it may prove necessary–as a provisional but important step in the reinvention of leftist arrangements–to invent collective spaces in which we can exercise the framing of our own problems.” And wouldn't it be “ironic to discover that 'communism' is a name that will gain historical reality in the 21st century as a method of dealing with 'non-antagonistic' contradictions within the left, before becoming itself as a strategy for transforming reality"?

By Other Communities

Having completed the Trilogia dos Afetos Políticos [Trilogy of Political Affections], a project that kept us busy for ten years, now Cia de Teatro Acidental begins a new stage, researching the "ways of being a crowd," the ways in which we group and stay together, living and collaborating for more than half of our lives. One of the main points of this research is the perception of internal differences, in a context where identities lead debate and theatrical production. So, if we are not a black theater group, nor a gay or trans theater group, nor a women's group, but also we are not a white, cis, straight, male collective. How to deal with our multiplicity and at the same time with what unites us, expanding the possibilities of what we understand as community?

There is still no answer to this question, which will guide us in the coming years. However, it is already possible to glimpse a first step: observing how these dissident or counter-hegemonic subjectivities have overcome the temptation of individual protagonism and explored other ways of being together on stage.

In Eu tenho uma história que se parece com a minha [I have a story that resembles mine] (2022), Tetembua Dandara invites the audience to a feast where we will meet her family, and particularly the women of that family, three generations with long activism history in the black movement. “What we did was build a space for the audience to enjoy time in the presence of these women,” explains the artist from São Paulo, who despite having worked for years in theater, now moves away from its standard procedures: “It’s about sharing time, rather than watching something.”23 Tetembua, her sister Mafoane, her mother Neuza and her grandmother Dirce (on stage at age 95), share with us not only the space (including a kitchen and a ball pit for children, who are also welcome), but also a lot of food–cooked on stage by Tetembua–and many stories. But the idea is also that these stories don't necessarily embody the ones you usually see in regular black theater: "Whiteness puts black bodies in certain specific places. Sometimes I show my project and people ask me: is it about samba, Candomblé? My grandmother doesn't have any samba traditions, she doesn't belong to Candomblé, nor Umbanda. And she's no less black because of it.” This way, performance makes it possible to “think and discuss blackness beyond stereotypes. We are bigger than the places they allow us. We don’t need to only tell stories about suffering, why not celebrate these women in life?”24 Or we could say: try to make a community beyond the common identity already available in popular production.

Isn't that what also guides Mato seco em chamas [Dry bush on fire] (2022)? A partnership between Brazilian filmmaker Adirley Queirós and Portuguese Joana Pimenta, the movie takes place in the community of Sol Nascente, in Ceilândia, where we follow the disobedient political resistance of three suburban women (and many other lesbian ex-convicts who gather around them) in a dystopian future taken over by neo-Nazi militias and very similar to the present; because fiction is constantly contaminated by the reality where it's built, flirting with documentary. This combination, revealing traces of collaborative creation (much rarer in cinema than in theater), allows us “to see bodies that resist collectively to the oppressions of everyday life and the harshness of precariousness, achieving moments of joy, fun and self-affirmation.”25

On the other hand, História do olho [Story of the Eye], play from the same year directed by Janaína Leite, is based on personal stories (following the author's research on the possibilities of documentary theater, but that has taken her far beyond the strict limits of this form) of several actors (and “non-actors”), whose diversity is their main feature. The theme that unites these testimonies is sexuality, taken from the book by Georges Bataille and brought to the scene together with this personal material, but especially dissident sexual practices, even as a professional activity.

But, while the cast might initially appear to be there to play the role of “experts” on the subject,26 the unfolding of the stories and the clash with the literary work increasingly reveal sex as a place of not-knowing, a fundamental condition for the desire that drives us all (and highly valued by Bataille, for whom “knowledge enslaves us” and “demands a certain stability of known things,” limiting us to a domain “where we recognize ourselves” and exclude any unpredictability).27 Every time the audience is invited to be part of that discussion, whether with their own stories, with their actions, or just with their glance, no longer distanced or naive. The diverse cast, and also ourselves, end up being part of a kind of chorus. Not because we have any common identity or because we agree on some point about reality. But because we allow ourselves not knowing together.

Every time the audience is invited to be part of that discussion, whether with their own stories, with their actions, or just with their glance, no longer distanced or naive. The diverse cast, and also ourselves, end up being part of a kind of chorus. Not because we have any common identity or because we agree on some point about reality. But because we allow ourselves not knowing together. [28]

After all, this non-knowledge is the starting point for any “common world” to be built today, according to Spanish philosopher Marina Garcés: if we are today in a desperate situation in which we “no longer know how to say 'us'”–because “between the self and the whole we don't know where to place our bonds, our complicities, our partnerships and solidarities”–it is precisely this “exposing ourselves to the that we don’t know” that can promote unity today, creating “an 'us' that doesn’t need identities, an 'us' with multiple anonymities, of words that don’t always say what we want, and bodies that do things we don’t know how to say.”29