Reading the World Before the Word: Post Neoconcrete Legacies and Decolonial Pedagogies

06/08/2022

Art as action could be liberated from pedestals, frames or buildings and intertwined with life, affecting and being affected by the everydayness of the world. The experiential and political dimension of such walking and dislocation resonates in various artistic practices in the 1960s and 70s.

[…] the matrix of popular education is not built on the principal of excluding the different, but on the radicality of the affirmation of the place from which one speaks.

Artist and critic Luis Camnitzer has suggested that in Latin America, “Freire’s belief that the reading of the world precedes the reading of the word could be taken as a paradigm for both conceptualist art and the new progressive teaching.”2 Literacy begins with the context of the learner. So would art. Indeed, as philosopher Enrique Dussel notes of liberation theology, this paradigm is a radically political praxis, one that deliberately chooses not to start with a body of discourse (art, education, literature, theology) but “from the state of affairs as they actually exist.”3 In a similar decolonial rejection of traditional academic methodologies, sociologist Orlando Fals Borda’s pioneered participatory action research in the 1960s, flipping hierarchical models and proposing a horizontal dynamic where subjects, researchers, and teachers alike can become “sentipensante” (feeling/thinking) affecting what he called a “symmetrical reciprocity.”4 Research is here engaged with collectively and results are critically socialized.

Within such paradigms of reading the world, Freire, like Cuban philosopher and writer José Marti before him, embraced a practice of “andarilhagem” (andar in Portuguese = ‘to walk’ and andarilho = ‘wanderer and pilgrim’)—literally walking around, a nomadic dwelling with otherness and oneself, an active praxis of encounter, a listening that engages and responds to people, contexts, and situations.5 Pedagogy, for Freire, is movement—a constant lived peregrination. It is also a movement in the world of ideas, challenging assumptions and schools of thought, a political and deliberate act of dislocation, and of opening up to time and the other. Such “walking,” as John Beverley has noted in relation to subaltern studies, is not only an option akin to liberation theology’s “listening to the poor,” but also, of dismantling “the relationships that construct the elite/subaltern distinction in the first place.”6

It is in the “plenitude” of praxis, of walking, as Freire7 notes, that we have the ability to affect and be affected simultaneously. Philosopher Brian Massumi sees this “affection” as two facets of the same event:

«One face is turned towards what you might be tempted to isolate as an object, the other toward what you might isolate as a subject. Here, they are two sides of the same coin. There is an affection, and it is happening in-between […] You start in the middle, as Deleuze always taught, with the dynamic unity of an event.»8

The potential for modes of inquiry and art practice of this “happening in-between” is aptly captured by the topological figure of the seemingly double- yet single-sided surface of the Möbius strip. Highlighting the paradoxical nature of binary oppositions, Jacques Lacan deployed the figure of the strip in his lectures on psychoanalysis. The artist Lygia Clark radically appropriated its “in-betweeness” to inaugurate her concept of the artist as proposer. Clark’s Caminhando [Walking] (1963) invited viewer/participants to simply cut along a paper version of the strip, making their own choices of direction, speed, width, time, etc. A revolution in the artist’s practice and a key moment of Brazilian avant-garde rupture, Caminhando shifted the emphasis from art as object to action and experience. Clark reworks the predetermined steel folds of Max Bill’s sculpture of the Möbius strip, Tripartite Unity (1948-49), awarded at the first São Paulo Biennial in 1951, to open up to chance and possibility.9 Instead of concrete form, the artist proposes momentum, choice, and duration as the distinguishing features—the space/process/time it takes to cut along the strip, creating what she called a “new concrete space time.”10 Instead of opposites there are rather foldings, or events as Massumi might term them, each inseparable from the other and the process itself, enacting, as Clark writes, an “interior itinerary outside of myself.”11 Art enables action and a way to see ourselves in the doing—walking, thinking, cutting, making.

Art as Action

Embracing a praxis similar to Freire’s “andarilhagem,” art as action could be liberated from pedestals, frames or buildings and intertwined with life, affecting and being affected by the everydayness of the world. The experiential and political dimension of such walking and dislocation resonates in various artistic practices in the 1960s and 70s, whether Cinema Novo filmmaker Glauber Rocha’s aesthetic of hunger or the artists Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica casting aside museums and galleries and launching themselves into the city in Delírios ambulatórios [Walking deliriums].12 For psychoanalyst and critic Suely Rolnik this shift into space, process, and experience, marks a drive to liberate art from its confinement to a specialized field, to maximize its transformative potential, to make of life a work of art and in this way to “contaminate art, social space and the life of citizens.”13 For artists such as Oiticica, Pape, and Clark, the concrete here and now of the world was a live canvas where artmaking could propose a conscious awareness of being/making/experiencing within it.

The Brazilian Neoconcrete art movement (1959-1961) had, as Pape noted, opened up new possibilities for artists, ones that laid the groundwork for an understanding of art as experience. Poet and critic Ferreira Gullar succintly articulated the movement’s desire to found a new expressive space and trigger affective signification in his “Theory of the Non-Object” (1959), noting that “the non-object is not an anti-object but a special object through which a synthesis of sensorial and mental experiences is intended to take place.”14 Yet political and social events would soon make radical demands on that sensoriality.

The monumentality and lack of human scale of Brazil’s modern capital Brasilia, inaugurated in 1960 and built from scratch in just three and a half years with its so-called “pilot plan”—imagined by urban planner Lúcio Costa with the collaboration of the architect Oscar Niemeyer—would underline the dramatic rise and fall of utopian modernist projects. The political context would similarly mirror a roller coaster of possibility and failure with the resignation of president Jânio Quadros in 1961, after less than a year in office, followed by an increase in political and social activism and mobilization of elite resistance during president João Goulart’s adminstration (1961-1964). These dueling forces ultimately paved the way for the 1964 military coup and the country’s twenty-year dictatorship (1964 – 1985). Amidst such failure and instability, the sensorial and experiential legacy of the Neoconcrete movement post 1961 would find itself infused with the micropolitics of what critic Mário Pedrosa saw as the potential of art to “revolutionize sensibility”15 and by a sense of urgency, as critic Roberto Pontual noted, to think through artmaking “at the heart of underdevelopment.”16

Concomitantly, the Cuban Revolution (1959) together with former African colonies’ wars of independence (Algeria, 1954-62, for example) similarly shaped an increasingly politicized awareness of what Oticica would later call “Subterrânia” (1969)—a Brazilian or Latin American “underground” that embraced the below-the-Equator conditions of “sub,” in ways that as art historian Irene Small notes, “acknowledged its historical and geographic specificity not as a limit but as a generating force.”17 Already by 1962, Gullar had radically shifted his formerly vanguardist position, or rather redirected its possibilities, and joined the recently formed Centre for Popular Culture (CPC).18 Affiliated with the National Student Union, the CPC strove to bring together diverse art forms where the potential of a revolutionary popular art was seen as a key instrument of social revolution. While such didactic instrumentality would be seen by most post neoconcrete artists as overly pamphleteering and limiting experimental possibilities, there was, nevertheless, a shared “appetite for the popular,” a spirit core to Cinema Novo, as noted by filmmaker Carlos Diegues.19 That is a kind of ethical aesthetic probing of the everyday, the political, and the participatory coupled with a search for new forms and formats. A taste for the popular, a turn to the other, revolutionizing sensibilities, and the politics of the subterranean would all mark emerging art practices and decolonial pedagogies of the time period.

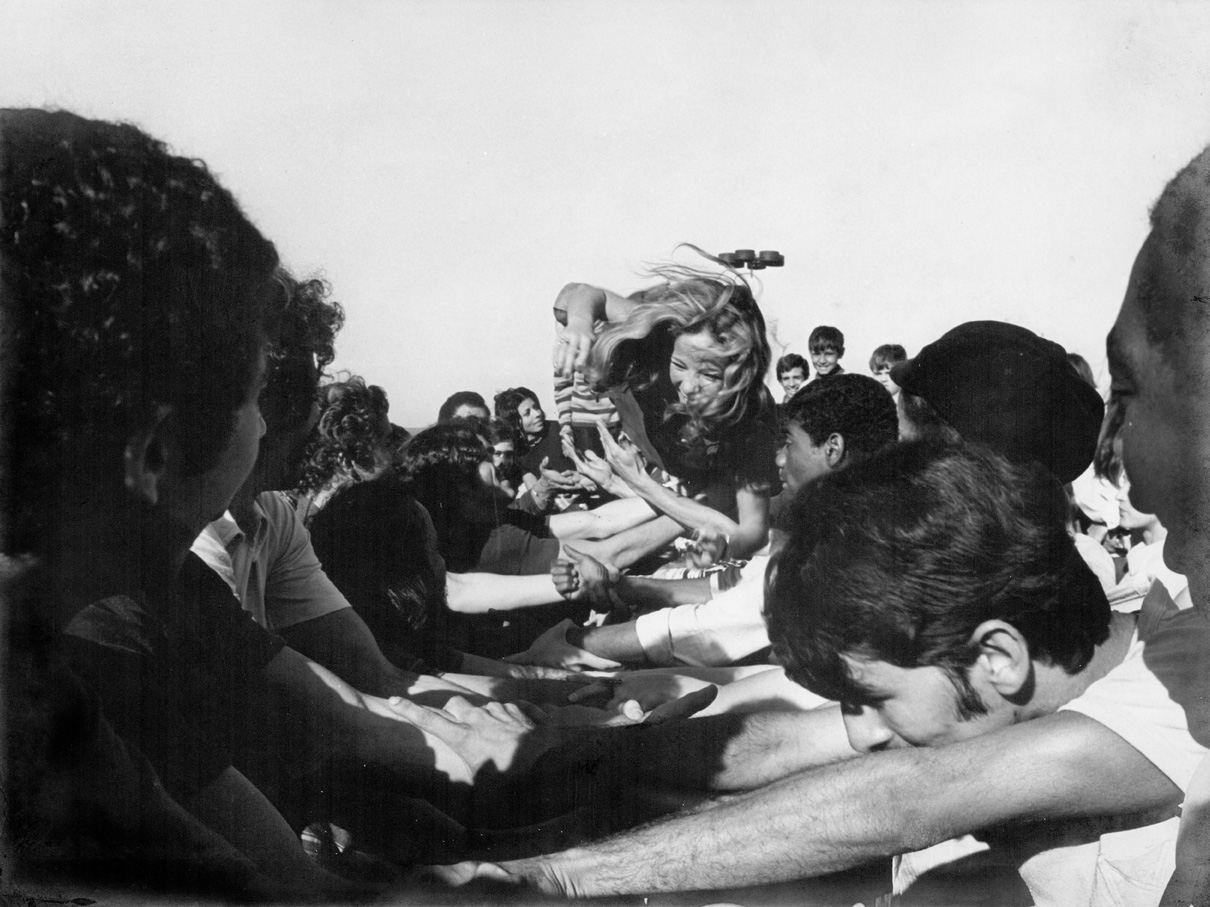

As a radical example of such synergies, in the spirit of Clark’s use of the Möbuis, and as equally revolutionary, Oiticica’s Parangolés (1964), featuring wearable capes, standards, and samba performers from Mangueira favela in Rio de Janeiro, similarly deployed momentum and art as action and awareness. Radically, the artist inverts an individual contemplative art experience to a collective participatory one of wearing and watching.20 Art here generates, as artist and activist Augusto Boal notes in Theatre of the Oppressed, the “capacity to observe ourselves in action.”21 It is in this respect that art has the potential to affect a kind of ontological education.

“Art,” the philosopher Fernando Pessoa proffers, “educates humans to, in caring for the word, bring being into speech.”22 In a climate of censorship and dictatorships (and one might add continuing gapping inequalities, social alienation, and resurgent contemporary fascisms) there is a political urgency to such art and education. Dictatorships insidiously operate through the control of the body and internalized oppressions. It is on the “micro” level where the political is felt and oppressions are experienced and in turn where micropolitical actions inscribe themselves within a performative plane.23 In this context, Pedrosa’s oft-repeated art as an “experimental exercise of freedom” is primary, but so too is connecting with others.24

As Camnitzer notes of Latin American conceptualism, art was also about organizing a receptive community. Here art, politics, pedagogy, and poetry could overlap, integrate and cross-pollinate into a whole.25 In Brazil, particularly post the dictatorship’s enactment of AI-5 of 1968—a constitutional act that limited freedom and political gatherings, paved the way for arrest and torture, and sent many artists and intellectuals into exile—creating contexts for experimentality, community, and connectivity became vital communal and artistic lifelines. The Museum of Modern Art (MAM) in Rio de Janeiro, first to present Neoconcrete exhibitions, would prove to play a key role in the post-movement’s plurisensorial unfoldings. The institution became what Pedrosa had presciently called in a brief 1960 article titled “Experimental art and museums”, a “para-laboratory”26 whether as a vital place of encounter in the museum’s canteen or as an expanded studio for what the artist Anna Bella Geiger called the “extra-artistic” experimental interest in education at the time.27

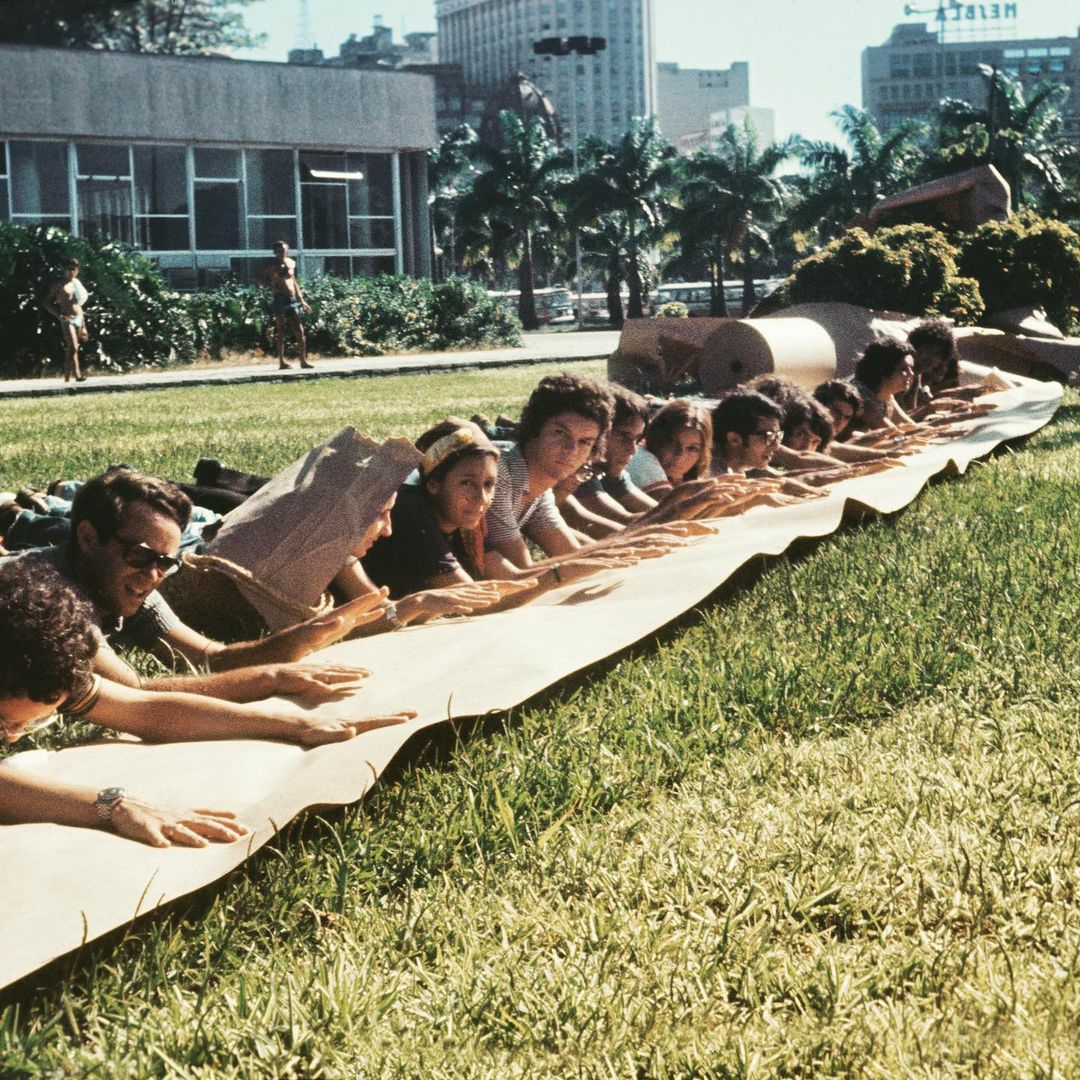

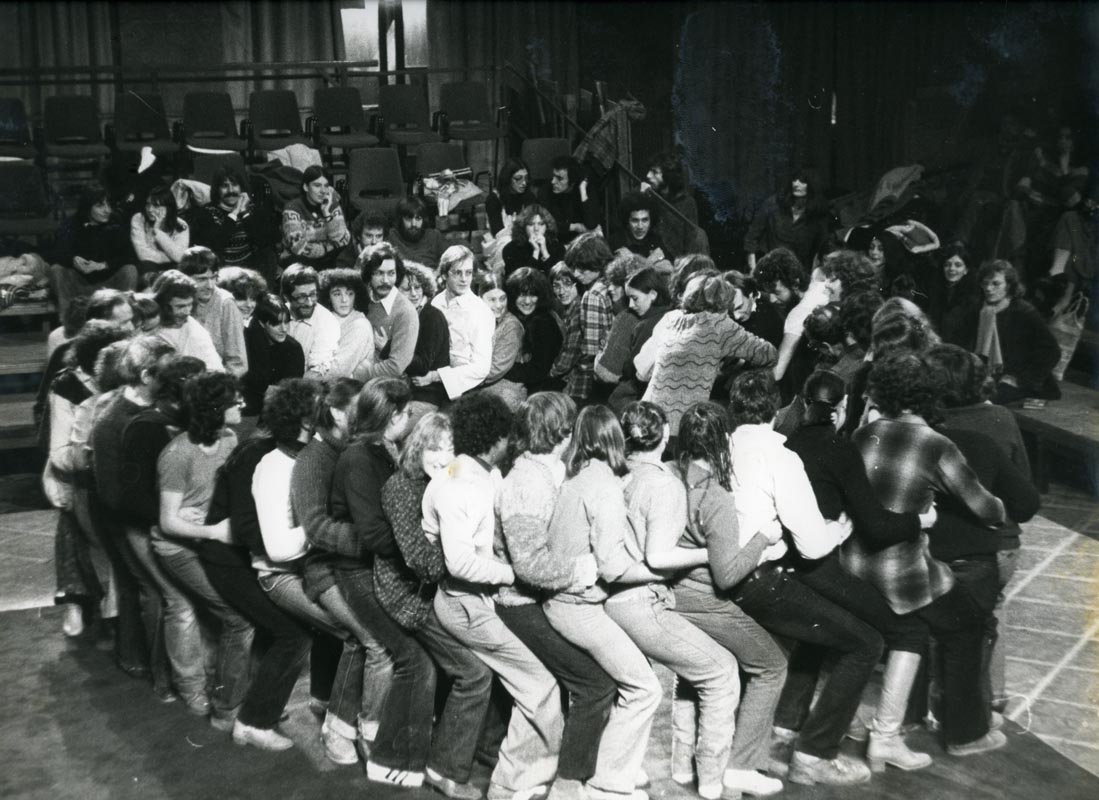

As director of courses at MAM-Rio together with artists teaching at the museum, critic and curator Frederico Morais created experimental courses and propositions, such as the free Curso Popular de Arte (Popular Art Course) on Sundays throughout 1969-1972. He also explored the city as an active terrain of art and education, teaching about pop art in supermarkets or hiring tractors to experience land art. Art was touted as an activity. A few fervent years of experimentation culminated in six participatory happenings called Domingos da Criação (Sundays of Creation) in 1971, held at the height of the military dictatorship. The events attracted thousands. Morais understood them as a type of mass sensory re-education, leveling a Marxist critique of the Bourgeois notion of Sunday entertainment.28 Countering the notion of leisure=non-activity, Morais embraced Hélio Oiticica’s concept of “crelazer” [creleisure], the artist’s neologism [creer = ‘to believe’ and lazer = ‘leisure’] advocating creative leisure.29 The events emphasized the simplicity of materials, the tactile, and the corporal. Each of the six Sundays had a particular material and conceptual theme that determined the nature of the day’s activities: paper, thread/wire, fabric, earth, sound, and body. The idea was to demonstrate that any material could be used to make art, but also to position an anthropophagic subversion. Using so-called waste as creative material both critiqued industrialization and countered the unstable image of a developing nation in an actual promotion of the precarious. The focus was on art as an activity not an object. What mattered most, Morais noted, was the process. A carnivalesque mix of art, education, party, playground, and protest, the Domingos were not only vital participatory happenings challenging museum and artistic boundaries, but also media ones, happening on newspaper front pages and daily news columns moving well beyond the traditional limits of cultural coverage and criticism.

Domingos collaborators, such as theater director Amir Haddad and choreographer Klauss Vianna, not unlike recent contemporary initiatives espousing practices of “de-skilling” and “unlearning,” as being both generatively creative and politically necessary, embraced in their use of street theater and dance movements, an active sensorial process they called de-education.30 Haddad would later joke that the “roda de conversa” (conversation circle) would become as much an oppressive tradition as the talking head but at the time it was part of a series of formats, attitudes, and practices that aimed to de-construct hegemonic narratives and modalities.31

Yet despite these synergies, the worlds of Freire’s politicized grassroots education and Pedrosa’s experimental artistic liberty would not meet. The 1950s and early 60s in Brazil saw significant divisions between those bearing the flags of socialist realism and popular cultural movements and the elite intellectual left – a rift that continues but that has also become an increasingly fertile ground for cross-pollination and new artistic, curatorial, educational, and scholarly possibilities. Regarding the latter, Irene Small, in her analysis of the praxes of Freire and Oiticica, recently parsed the parallels and contrasts of experimental art and alternative education.32 Both artist and educator aimed at the “liberation” of the subject through notions of participation. Freire saw creative practice as a means to literacy and political and existential freedom. Oiticica was more interested in open structures allowing for creative possibility that while they may change behavior and prompt action, they can only do so by their phenomenological sense of suspended openness.

This tension between the open-ended and the consequential, the possible and the necessary, and how they might be understood, facilitated, and navigated, or rather how one might ventilate or puncture the other, is the entanglement of art and education. Not to be resolved but lived. Walked. Like Clark’s use of the Möbius strip, a consciously engaged practice of momentum, merging art and life to occasionally affect what the artist called the “singular state of art without art”.33 It is here were a possible encounter of post Neoconcrete legacies and decolonial pedagogies might productively entangle, reading the world before the word, walking, in the plenitude of praxis where, as Freire suggests, “education is simultaneously an act of knowing, a political art, and an artistic event.”34