The pedagogy of CAP:

— Right to make mistakes.

— Close, affectionate relationships. Support, companionship.

— It is not about training artists, it is about using art as a tool to think, to do. — — — Integral formation of a human being.

— Decolonizing conceptual artistic practices and imaginaries; letting in the knowledge of life.

— Create interpersonal links, with nature and context to activate the ability to solve problems. Creativity.

— Constantly revise work/premises.

— Focus on technique, but with strong cognitive and emotional charge.

— Biopsychosocial perspective on health.

Urgency, Affection and Informality: Pedagogy and Contemporary Art in Central America

03/28/2023

The fact that the three projects [CAP, Escuela Experimental de Arte, and EspIRA] are based on affective pedagogies is the outcome of experiential and contextual knowledge of their territories. A little bit a consequence of the hostility and shortcomings of the context, but also a reflection of a practice born from conviction.

A common feeling we share in Central America is that of invisibility. Our friends in Mexico don't know exactly what the map of this region looks like; our friends in the south of the continent don't even know where to locate us on the map; even within the same research spaces, the calls for papers, the round tables, the presentations, Central American themes are excluded. In spite of this invisibilization, there are particular experiences in this region and, consequently, a production of knowledge that is manifested in ways of doing, in artistic practices, in academic texts or in informal mappings. But it is not a knowledge that is easily recognized or legitimized.

The field of art+education is not excluded from these dynamics. In 2018, with LaRuidosaOficina and our sister collective from Mexico, Cuerpo Estratégico, we organized what we wanted to be a Central American meeting of mediation/art, art education/education, in which we could bring together the experiences, strategies and methodologies of various people or collectives from Central America, putting into dialogue the characteristics of each particular context, in order to map the mediation networks in these territories. The exercise was by no means successful, as the funding we obtained came from an international cooperation agency based in Mexico, which had its own goals to achieve that did not meet ours.

A little because of the persistence of the same questions and a little because of the debt and the emptiness left by that meeting, is that I decided to make this small mapping of self-managed spaces for education in artistic practices. These projects are the CAP (Creatorio Artístico Pedagógico) in Guatemala, the Escuela Experimental de Arte (EAT) in Honduras, and EspIRA (Espacio de Investigación y Reflexión para el Arte) in Nicaragua. Some schools are more silent than others, but all have been fundamental in the teaching-learning of art as a practice of situated and Central American thinking.

CAP – Creatorio Artístico Pedagógico (Guatemala)

The day Espe shared her work from the CAP at the Central American Mediation Meeting ENSAMBLES, the first thing she did was to share with us some data about Guatemala: its poverty and social inequality rates, its literacy rates, as well as statistics on malnutrition in indigenous populations, the majority of the country's population. All this information was her context and her motivation to talk about the needs and urgencies of education projects from the arts in Guatemala.

Esperanza de León is a visual artist and psychologist; Flor Yoque is a visual artist and pedagogue. Together they are pioneers in the field of artistic pedagogy in Guatemala and founders of CAP. CAP is a space for artistic and pedagogical creation based on artistic thought and professional therapeutic accompaniment, aimed at children and young people. It is grounded on three actions: 1) curricular research, 2) production of art works, exhibitions and knowledge, 3) training of other facilitators.1

CAP was born under this name in 2012, but they had known each other since 1996 in the workshop of artist Daniel Schafer, at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (ENAP). They recognized each other by sharing frustrations and desires. When, years later, the Ministry of Education opened the call to reform the national plastic arts curriculum, they applied and were selected. Together with artist Jorge de León, they worked for four years; during that time they wrote a book, trained teachers and traveled around Guatemala to evaluate the implementation of the program. Later, they were part of the reform of the Escuela Municipal de Arte in Guatemala City, for which they used their own working models.2 Later, in 2018, Alejandro Palacios joined as the CAP bench's third leg.

For them, the relationship between art and education has to do with collectivity, circularity, experientiality, creative thinking and research curiosity; it is learning in itself.

During a certain period of time, CAP functioned as a permanent training space, although it was not intended to be an artistic training program, but was imagined as a project to provide artistic, expressive and emotional tools to young people in different conditions. As an accompaniment and support to regular academic training.

The directors participate in the facilitation, but only in part, as they invite other artists to teach the workshops. In the same collaborative spirit, they have approached artistic and cultural institutions with which they have organized exhibitions that allow them to make their students' work visible.

According to Esperanza, the program was suspended in 2020 because of the pandemic and has not yet returned in its pedagogical format. However, this two-year pause has been a chance to review their memories and share what has been done for more than eight years. A book-memoir on the work of CAP will be published at the end of this year (2022). After that they will reactivate the training program. They have slowed down but they are not stopping, they now prioritize self-care and are more aware of the limits of their capabilities in order to be able to continue their work, without wearing themselves out.

EAT – Escuela Experimental de Arte (Honduras)

Honduras is one of the most violent countries with one of the highest poverty rates in the world; it is also one of the most dangerous for environmental or human rights defenders. This implies that the priorities of daily life are focused on survival. Perhaps that is why there are not many art spaces, galleries or museums. Even so, none of this implies that there are no people with expressive and creative needs, with knowledge, with questions and with the desire to learn and share with others.

Lucy Argueta and Léster Rodriguez formed EAT in 2010, with the intention of exploring the teaching-learning of artistic practices. It consists of projects, platforms and courses that correspond to creation laboratories for contemporary practices, spaces for accompanying the professional development of emerging artists and training processes in the field of arts and crafts in impoverished communities. They developed a methodology based on their experiences as artists, as well as the deficiencies and needs they observed.3

Plataforma Nómada4 is the name given to the training program in contemporary practices with which they have accompanied processes of creation, research and professionalization of emerging artists. Articulating dialogues, reflections, research/creation processes and their relationship with the context, culture and politics characterize the program.

Originally, like CAP, it was conceived as a more permanent and collective training space, with four-month long processes through weekly meetings. Nómada came to have five consecutive editions, each with its own theme. At the end of each module, an artist was invited and an exhibition was held with them, where they also had the curatorial and installation experience. Moreover, in all editions they have had the collaboration of other institutions, such as the Cultural Center of Spain in Tegucigalpa or TEOR/éTica Foundation.

They also taught an artistic management module where they shared professionalization tools: how to present portfolios, proposals and/or a work in progress.

The training workshops for micro-enterprises with arts and crafts functioned as spaces to provide creative production tools through silk-screen printing, design and carpentry workshops.

The pedagogy of the EAT:

— Non-formality allows for more creative freedom and freedom of thought.

— The question as a starting point. Analyze artistic production as a reflection on the world.

— Not imposing a unilateral structure of thought.

— Work with people who have experience in art. Engage in dialogue in relation to their context. Horizontal, everyday relationships.

— Art cannot be taught but we can learn from the processes of others.

— Thinking about education in a dialectical way, relating theory and praxis.

— Work on the process.

EAT closed programs in 2015 in Honduras. Lester and Lucy moved to Colombia and in the time of pause, reflected on the project. In 2017, in collaboration with the Bogota Art Fair, they designed the ARTBO tutor educational platform, inspired by the EAT curriculum. From Bogota they never stop looking towards Honduras, therefore in 2019 they resumed the Plataforma Nómada from there, in a much shorter and intensive format, but with an idea of a more regional scope. In August 2022 they took the program to Nicaragua and again to Honduras. They have also been working on a publication on art and pedagogy in Central America, with support from the Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo in San José.

EspIRA – Espacio de Investigación y Reflexión para el Arte (Nicaragua)

Sitting on the ENSAMBLES panel, Patricia talks about the harsh reality of Nicaragua, a country living under a dynastic and fundamentalist dictatorship, which has been in charge of disappearing the opposition, silencing criticism and ending any minimal resistance.

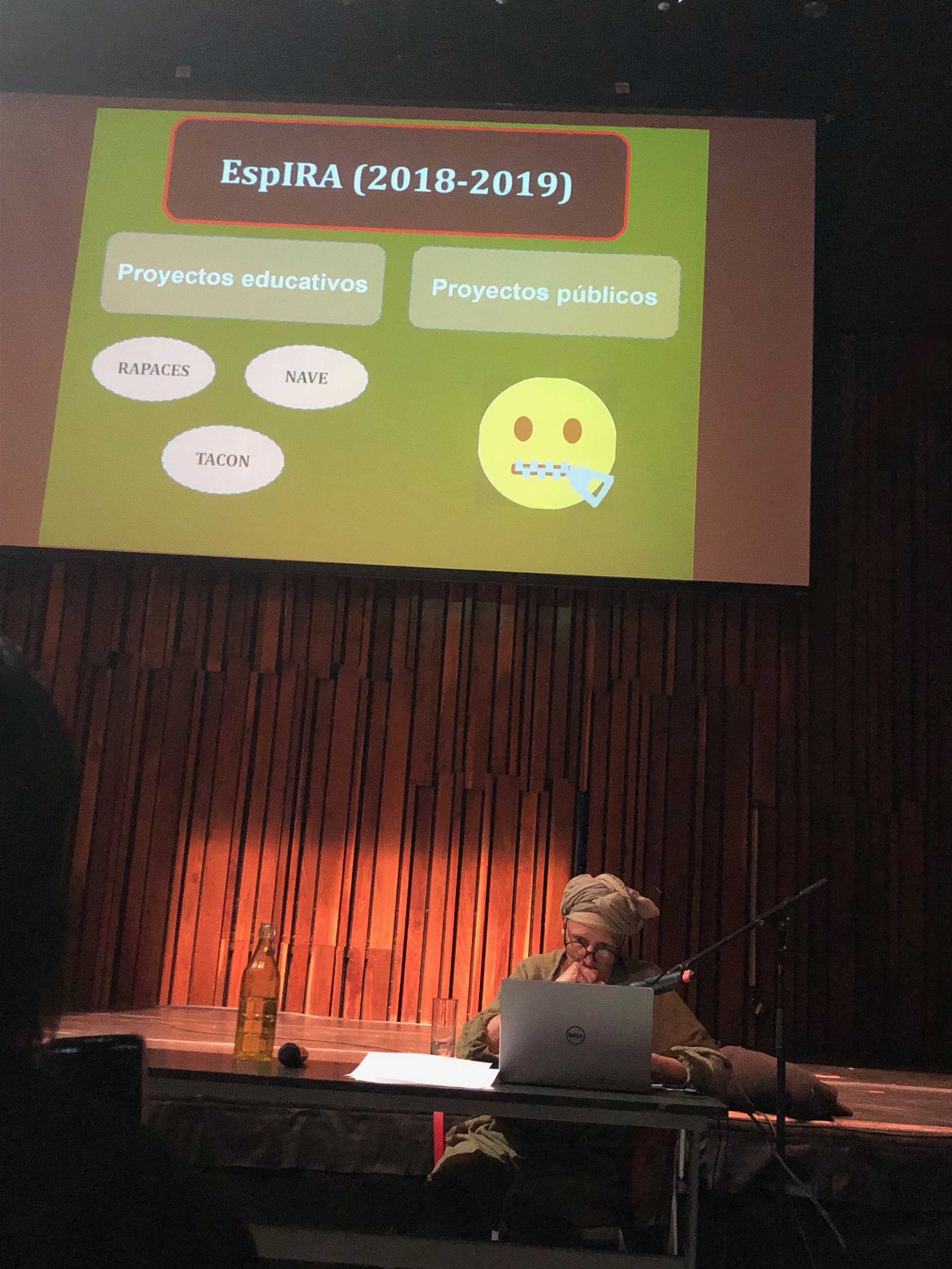

Since 2018, the year in which Ortega-Murillo assassinated hundreds of students who rose up against the factual violence of his power, EspIRA had to reduce its pace of work, lower its tone, to avoid any kind of persecution. The workshops became spaces for accompaniment and catharsis, then they had to look for regional alliances to carry out some projects outside Nicaragua, finally, due to security issues, they took the hard decision to end their legal status in 2021, and with that, to close a cycle definitively.

EspIRA was formally born in 2004 and became the most important space for cultural management around contemporary art in Nicaragua and the region. In 2001 Patricia Belli returned from studying in San Francisco with an enormous desire to consolidate a school. She felt the need for an artistic practice and teaching that could be based on experiences and dialogue. Thus was born the Taller de Arte Joven (TAJO), as the first antecedent of a space for those who wanted to bring their works into dialogue and discuss transversal art themes. Over time, more activities were added to the project. According to Belli, those who formed the TAJO space were the first artists who demonstrated that contemporary art could be made in Nicaragua (TEORéTica, 2015).

Like EAT, it emerges as a platform where diverse projects coexist, mostly focused on art education with a critical, political and situated sense. Some of these programs are:

— ESPORA (2004) is the name of the Escuela Superior de Arte that Patricia was creating. It implied the legal formalization of the project.

— TACON (2005) Talleres de Arte Contemporáneo (Contemporary Art Workshops) was an artistic professionalization project for young people over 18 years of age. Its methodologies were based on learning by doing and continuous training.

— RAPACES (2007) is the Academic Residency Program for Emerging Central American Artists, whose purpose was to build links between creators of the region to develop critical thinking and formal strategies of Central American artistic production.

For Patricia, most artists were critical of their contexts, but none of them were working self-critically or based on their personal experiences. Thus, the círculos de crítica (circles of criticism) were born as a response to this absence. These are spaces in which everyone has the commitment to participate, no one can only be an observer. The dynamic was to observe a piece and discover what it said in itself, then, the creator explained their communicative intentions and the rest listened actively until the moment when everyone could give their opinion. The criteria were communicative successes or failures, strengths or inconsistencies.

EspIRA's pedagogy:

— The collective.

— Discovering and listening to the other.

— Dialogue and collaboration.

— Experience crossed by a way of being/doing.

— Horizontality and everyday life.

— Curiosity.

— Commitment to questioning. Building the desire to question.

— Discovering, not dominating.

— Empathy. Collective well-being as pleasure.

— No interest in homogenizing thinking.

— Promote people's self-determination.

— Not representing the other.

— Critical and self-critical thinking.

— Detachment from the ego.

— The circle as a device.

— Feminist education both in workshops and within the organization.

The fact that the three projects are based on affective pedagogies is the outcome of experiential and contextual knowledge of their territories. A little bit a consequence of the hostility and shortcomings of the context, but also a reflection of a practice born from conviction. The lack of institutional spaces can be an impulse to fill these deficiencies from more flexible places, thus generating different and less canonical methodologies, riskier and freer, since error, revision and self-questioning are allowed.

At the same time, this informality hinders the sustainability of the projects. All of them, regardless of the pandemic, have had to transform their programs to smaller, shorter and more intensive formats, and have had to establish relationships with institutional spaces. It is surprising, however, that in spite of everything there is so much persistence in each project to continue to exist. The extreme case of EspIRA responds to very particular circumstances of the dictatorship's violence in their country, but in spite of that, its seeds continue to fly throughout Central America, in several generations of artists who are active and continue to meet, as well as in their replicated methodology.

The three are projects that are thought from a collaborative point of view, with a core that leads a guide, accompanied by other artists and allies, to make them possible. These collaborative networks are expressed in the facilitators' participation and through economic, material or sponsorship support.

As a result, there is a woven network, which is not necessarily visible, but is palpable when a regional project is born: there are emotional ties between those who participated in the residencies and exchanges. Thanks to EspIRA, it is possible to speak of an imprint of what is created from the Central American context in its own belonging and place of enunciation.

Despite the warmth of the network and the freedom in informality, it must be recognized that security and the possibilities of more formal spaces, in a context as fragile as the Central American one, are not enough. Other economic and social circumstances might have prevented Léster and Lucy from migrating from Honduras; at CAP they continue to scrape with their fingernails to prioritize their survival, while at the same time sustaining the urgent. EspIRA's memory is based on very shaky ground that could collapse at any moment. The management of urgencies in Central America clearly does not end with these pedagogical proposals, but they are undoubtedly a fresh wind in the midst of the heat.