La Escuela___: Over time, the ideal of "education for all" has been a driving force for many Latin American thinkers. At the time, regarding this, Carlos Cruz-Diez said that the visual arts could never fulfill a massification of their teaching, for they would not be creating artists but artisans. In your case, Nelson, you founded a school that has trained a sizeable number of artists, how do concepts such as technique, craft, and craftsmanship dialogue with others such as art, thought, and authenticity?

Education as a System of Freedom

05/12/2022

with Nelson Garrido

Carlos Cruz-Diez (Caracas, Venezuela, 1923 — Paris, France, 2019) was a contemporary artist, regarded as one of the key 20th-century researchers in the realm of color. Many of his works of monumental proportions are placed in urban public spaces around the world. He was also a fantastic teacher, who transmitted his technical knowledge and work ethic to a large number of artists he received in his workshop, both in Paris and later in Panama. Among them is Nelson Garrido (Caracas, 1952), a photographer, teacher, and professional agitator; he received the National Prize of Visual Arts (1991) and founded the formative and exhibition space Organización Nelson Garrido (La ONG), in Caracas, from where he talks to La Escuela___ about learning, critical training, and educational rituals.

Nelson Garrido: I start out from the fact that knowledge makes sense as long as it circulates, but this “education for all,” in the name of the people or democratization, is nothing but a sham. In fact, I believe certain medieval notions around education should be rescued.

I arrived very young at the Cruz-Diez workshop and my whole way of understanding art and education comes from the training I received as his apprentice—in the sense of the medieval concept of 'apprentice.' I do believe it is necessary to teach a basic trade that is to be fully mastered; if the person chooses to use it to express something artistically, that would be a second stage, but you cannot deny people the teaching of the techniques that produce artists.

One thing I insist on is constant, almost scientific, studio work and reflection; that was Cruz-Diez’s approach, he trained me this way. Everybody has something to say, so we need to teach how to express it. But the most important of all is to create critical people. I make formal criticism with my training workshops.

Of course, and when you begin to see art as a means of research and reflection, you also begin to open up possibilities to work on these critical aspects.

Another issue that Cruz-Diez raised when talking about education in Venezuela was that it is predominantly behaviorist, uncritical, and hegemonic. With your teaching experience in the field of art, what do you think is the role of art education in a country in crisis?

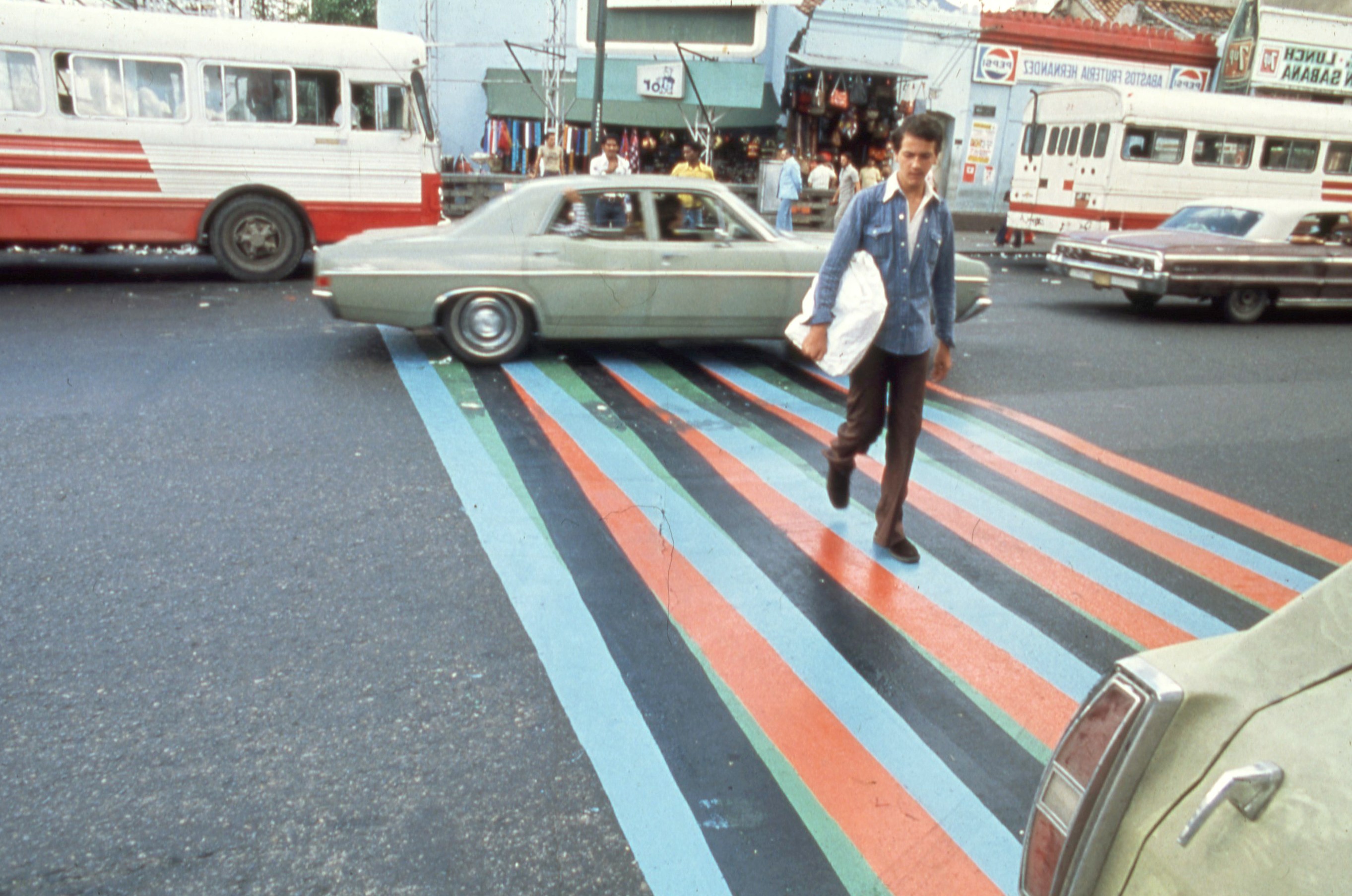

Education is living a crisis all over the world. It begins with the prohibition of error and clipping diversity because everyone has to arrive at the same result. From kindergarten, we are castrated towards a single way of seeing things and this is unacceptable, we have to rethink education as a system of freedom, as a practice of individualities and differences. So before talking about what its role should be, we should take care of generating critical people, who question the teacher, because that hegemonic concept can go on from the school to the workshop, and it is about creating an education that is a practice of freedom. Here is an example that accompanies and guides me: for me, the most important thing about my training with Cruz-Diez is that I did not come out making little stripes. That is my notion of a teacher, of critical training, where everyone develops their own expressions and languages, raising the problem of diversity in the artwork from the beginning.

In a society that respects individuality, education is oriented towards the interests of each one’s personality and it instructs that inner world, rather than making impositions. Students cannot be conceived of as containers to stuff information in. Moreover, information is one thing and knowledge is another: knowledge is digesting information; the biggest problem with formal education is that it is conceived of as accumulating information. And now with the internet, people say we have "access to everything," but what we have is access to information, not to knowledge.

In the formal concept of education, there is another key element to reconsider: time. I am calling, firstly, for the right to make mistakes in the training system and as a form of creation, and secondly, for the right to slowness. What is the rush? Why are we in such a hurry and everything has to go so fast? Everyone has a rhythm, you cannot impose a single tempo on everybody; we must recover the process of sifting knowledge. Knowledge comes from rigorous training, whether it is in art or science. We are living in a society where opinion prevails over knowledge, the "right to opine" in the name of the people... in the name of the people we are screwed as we are! What place are we giving knowledge?

Your relationship with Cruz-Diez is striking and little known. It is interesting how such dissimilar practices coincide on much deeper aspects, this speaks well of you but it speaks even better of Cruz-Diez as a teacher. How did you become his apprentice?

I arrived at the age of 14 to Cruz-Diez’s workshop in Paris because my dad was an attaché in France and they were close. My dad painted, but being a military man, he was ashamed to sign the paintings, so I did and he would say his son was a painter.

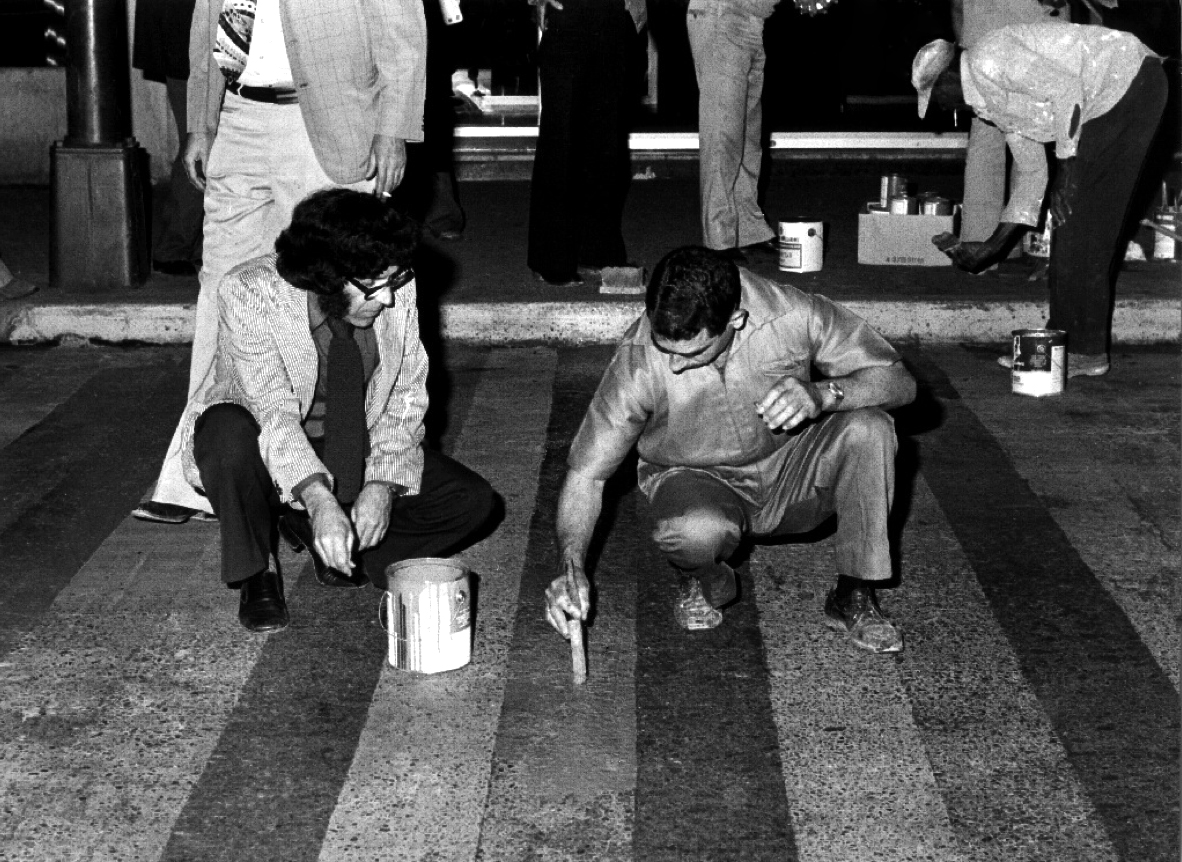

So when he became interested in making the little stripes, he sent me to Cruz-Diez's workshop as a spy. The problem was that the master opened up an extraordinary world of learning for me and I started sneaking out of school to go to his house. I commenced as medieval apprentices did—and this is something I also practice at La ONG—: sweeping! Because the first thing is to form modest people, for knowledge without humility can create dreadfully arrogant little monsters. It is important to foster a sense of service to others.

How do you bring this training into your own pedagogical practice? How do you see the relationship with your students?

The most important thing is the critical and comprehensive training, that is, to hold spaces where criticizing the teacher is seen in a positive way; to teach photography while also teaching about philosophy, painting, architecture, music, sexuality... I want my students to be free and happy in their learning, not to be useful or to be artists, but to be happy. But how do you transmit this thinking?

I always had apprentices, as Cruz-Diez taught me. As a result of migration, many of them left Venezuela, and then it happened that knowledge began to grow organically: now there is La ONG – Buenos Aires, Santiago, Madrid; spaces led by disciples of mine and linked to other local collectives, which also reproduce the system of transmitting knowledge, since they, in turn, are training disciples. It is a very beautiful, almost Masonic, concept of 'forming a school' that Cruz-Diez planted in me.

Such school dynamics weave ample, diverse, conveying bonds. What place does collectiveness have in them?

Collectivity must be based on respect for the individual; diversity is a personal feature. In this spirit, the motto of La ONG is 'the space of those who have no space.' Formal education castrates and condemns all that is different, so we must create spaces of diverse, open, free liberties, which allow for creating critical bonds.

We must look for new forms of teaching which are training processes, where people come together and the teacher just lays out certain alchemical elements to perform the fusion, but it is the students who must do it. I prefer a pupil’s mistake than to tell him what "the right way" is because that is very relative and I would be distorting him to my opinion. Every pupil deserves respect; they will gradually grow.

Right now, my role is to be a platform for others to learn; it is about being humble and not abusing power. We must create a new humanism around teaching.

How did this collective idea of dialogue function at Cruz-Diez’s workshop? Was it a collective workshop?

Not really, it was a totally vertical workshop because it was another structure, it was not a school, and it is something I am objectively grateful for. That verticality taught me something important: to be strict, disciplined, systematic. Also: collectiveness is one thing and collectivism is another. In my workshop, everything happens in a community but respecting individuality. Students correct me, give me tips, and so I learn, but you have to be open to make mistakes or to say I don’t know; that was also a teaching of Cruz-Diez. If you ask questions, people explain and you learn. So make mistakes and ask when you don’t know.

Is your need for creating learning spaces of liberty somehow related to your anarchist practices?

Yes, I am a utopian anarchist and I believe deeply in this thinking. My main philosophy is my daily practice: every day you stake your freedom and determine your philosophical position towards life. I continuously doubt and question myself, and I transmit the right to doubt.

I agree with an anarchist philosopher named Hakim Bey, who talks about 'temporary autonomous zones,' new forms of organization that are not interested in seizing power. It is about making every space you get involved with a temporary autonomous zone. I do not believe in institutions, I believe in the particular: teaching and my personal work are the fields where I can transform and perform my anarchist practices. How to approach teaching from these personal practices? The hierarchy must be desacralized and renewed teaching practices created: each class should be a challenge to do things differently, not a reproduction.

Education has to be like homeopathic medicine: you put together several critical elements that then explode in each person in a particular way. You must provide seeds, not saturate with information; let them do research. To understand education as a meeting point to stimulate research, not to feed the rhetoric of knowledge in which students speak quoting references and statistics that they don’t really know. Critical training is not about accumulating information but about encouraging research, which is the quest for a particular knowledge on the basis of your personal process.

You speak of formative spaces as transformative spaces, how do you think public art can transform a certain reality?

I will be cruel: that seems absolutely absurd to me—and yet, it has to be done. Art’s transformative power is on another level, far deeper than attendance statistics. Drop by drop work is what can transform a sector or certain practices in a critical way.

A real urban intervention would be, for example, if we had a say in the schools’ curricula or things with a greater impact on people's lives. But the State is not interested in raising critical people, we are fighting a massive monster. Artists are still a minority and as a minority we should to work; that is why I return to guerrilla art, to peripheral art, to create hotspots of agitation. Before being an artist, I am a professional agitator.

Creating critical people is very important because that is to create agents of transformation, and this is how art, science, and society advance, through ruptures. That is why I believe more in this constant formative work, in creating critical spaces, temporary autonomous zones.

You have said many things that resonate with us. Incidentally, the Naked School’s guiding principle is to bring art education closer to real contexts. Do you believe that education can be an artistic practice in itself?

For me, the practice of service with your knowledge, which is not supposed to be artwork, is the grand work. I offer a service of knowledge, I don't care whether it is called 'art' or not; that is my activity as a social individual. Deep down, art, the teaching practice, is an excuse to talk about philosophies of life. But how to democratize education in a practical sense? How to make it horizontal without losing the rituals? Originally, art was something that shamans did, it was magical objects that healed the community. Art and education need to return to the shamanic event of ritual. If education loses ritual, it is lost.

Current times have altered many practices, how has been your transition towards virtuality?

I think it is important to sustain personal interactions, but even before the pandemic we started setting up online workshops. The ritual is there too because that happens on another level. I find it very pleasant to teach students from different countries; that interconnectedness is part of the new rituals. The problem is not the medium but the ways of transmitting knowledge, whoever does it must have respectability and credibility because if you do not respect the teacher, you will not believe what he says. That is why I teach with what I have done, learned, and been mistaken; it is precisely my mistakes that make up my knowledge, that is why I set out showing my weaknesses. Thus, the connection occurs in other ways, it is the power of the collective ritual.

We have circled the topic of the influence of art and education on the practical life of people, specifically in your case, in what ways do you feel that the teaching practice has altered or influenced your reality?

It has absolutely influenced me. I was convinced that I did not know how to teach, and then teaching changed my life and keeps changing me every day. If we assume that one changes over time, that transformation is also reflected in the workshops, because I learn with them.

Thinking about how to express what you know to another, transmitting your knowledge implies observation towards your own practice, elaborating the thought of how you do it to communicate it to another. In order to give, you have to know what you are giving, what you do know and what you don’t. Teaching has made me do a lot of research and it constantly changes parameters for me. By engaging in practices of freedom, one is the first to experience freedom.

Lastly, outside of art, do you feel linked to Carlos Cruz-Diez in any other way?

Assuming the concept of being a teacher is important. In addition to his vast artistic production, his legacy lies in having passed on his knowledge to many. The great work is the transmission of thought. He is alive in me because he trained me, taught me to teach. That is his great legacy and it is not measurable, like light.

I always keep him in mind: his smile, his generosity. He acted as a shaman, influencing social changes by teaching, and that is non-measurable public art. His thinking influenced me just as my thinking will influence my disciples, who in turn will train other people, and that is fantastic. For me, that is art, not the object.