La Escuela___: Under what circumstances did you meet Diego Barboza?

The Work Exists While It Is Created

06/18/2022

with Marialejandra Maza

Diego Barboza (1945–2003) was a pioneer of Venezuelan action art, known for his expressions in public spaces carried out in several cities around the world in the 1970s. His words, conveying and persuasive, are 'activated' on this occasion in a conversation between La Escuela___ and Marialejandra Maza, a researcher, educator, collections safeguarding specialist, and a close friend of Diego Barboza, who tells us about her experiences with the artist from her current home in Lima, Peru.

Marialejandra Maza: I met Diego in the 1990s, when I was working at the Gallery of National Art (GAN) in Venezuela. I had the opportunity of sharing with him in many activities of the museum’s Education Department, of which I was a part at the time. However, it was in 2000, in the exhibition El festín de la nostalgia [The Feast of Nostalgia] (curated by Katherine Chacón), that I became very close to Diego and the Barboza family, especially to his wife Doris Spencer and Claudia, his daughter.

I remember very fondly a time when Claudia grabbed my arm and gave me a guided tour of the room with her dad’s paintings, while telling me which ones had been intervened by her, and how Claudia's childish voice expressed each of the work's processes—which perhaps her dad explained to her at some point or which she lived, because she was part of that same vital and everyday process.

To my surprise, one Saturday afternoon, I got a call from Diego and he said: "I need you to come to my house urgently. I'm going to die and I want you to come be with me and help me out." When I arrived, he asked several things of me: He wanted a documentary that showed his life as a human being and that would allow him to explain the relationship between his actions, his pictorial work, his personal history, and his family—that is, his concept of 'art and life'. He also wanted me to keep Doris and Claudia company in the face of his absence and, as a last request, to safeguard his memory to be transmitted on to future generations. A huge commitment that still implies a big challenge.

Concepts such as nostalgia, the past, and childhood are recurring around Barboza’s works, why?

I knew a Diego that spoke from a different perspective, so I saw no nostalgia in him; perhaps for his certainty of dying soon. But indeed, Diego was marked by his childhood in many ways: his childhood memories were recurring, his longing to paint his relationship with his mother and his family relationship, which was always close to him. On the other hand, I know that when he was in London, Diego missed the characteristically colorful and festive nature of Venezuelan culture, especially that of his native Maracaibo.

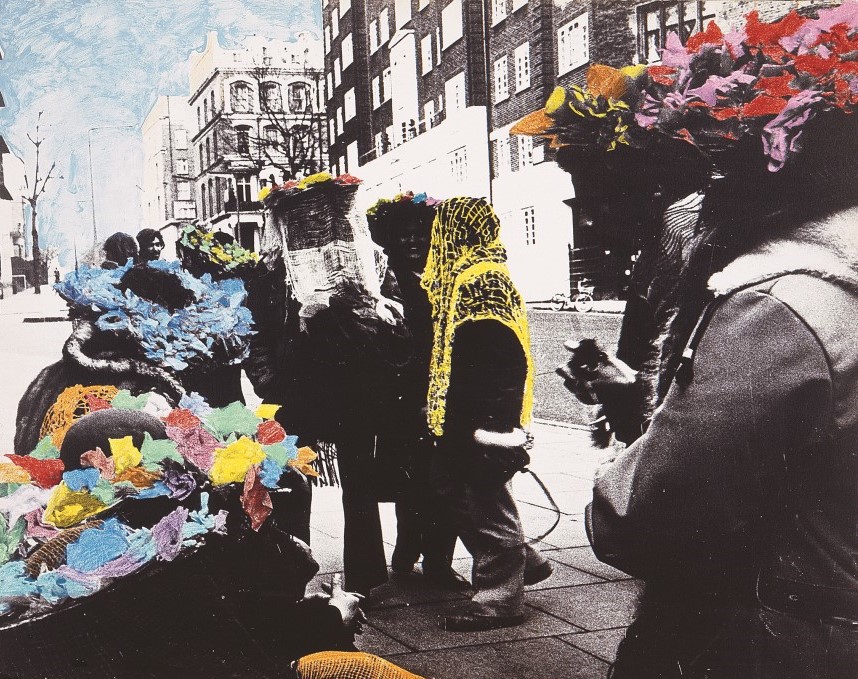

Conceiving actions such as Redes y sombreros [Nets and Hats] (1970) and 30 muchachas con redes [30 Girls with Nets] (1970) was his way—as a creator and as a human being—to channel those feelings of longing. Past and present always cross in Diego, for attempting to catch time was a constant desire of his. His works activate the construction of a chain that intersects persistent memories, in a space that we call memory and the creation of a new immediate reality, which partly materializes from a now that becomes a future eternally projected in the image, the written word or the oral story. Past and present dwell in his works and are active in the memory of each of the people he told something to or who participated in his actions.

It is difficult to classify Diego Barboza’s work in terms of technique or language, but it is possible to know what it isn’t (it’s not entirely performance, it’s not fully a happening). What did he call them?

When artists can’t find a concept that ‘fits’ them, they become makers of their own concepts, to explain what they’re doing in their own words. In Diego's case, he called his works ‘events’, ‘expressions’, and ‘action poetry’, depending on when he performed them. Toward 1985, Diego writes about his action poetry: “[it] is the relationship between art and life, the search for human harmony, of the poetry that is created through communication, a new form of expression, new and universal, of expressing our experiences and realities, a fiction of the future." At another time in that same year, in the framework of his 10 years of actions, he declared that their purpose "was to trigger psychological situations in the passerby and the feeling created was as important as life itself." Artists can rename their works as time goes by. He said so himself: "The work exists while it is created-consumed."

And were these poetic actions driven by artistic enjoyment or by social criticism?

The ‘action poetry’, ‘events’ and ‘expressions’ dealt with enjoyment in themselves, but with a questioning message. All actions included an artistic-activating element, and although each has a different proposition and dynamics, they are grouped into a common poetic universe. If we look closely at the photographs, we can see the reactions of the people who were there at the time: they are noticing the element, they are stopping at the action, and that was their function, to disrupt. A search that was very different from other manifestations of the time, for this disruption implied an intangible spirit and a contagious emotion that allowed to rethink everyday life. Therefore, according to Diego, they were carried out "in those places where people go to any given day to carry out regular activities."

Activities such as which?

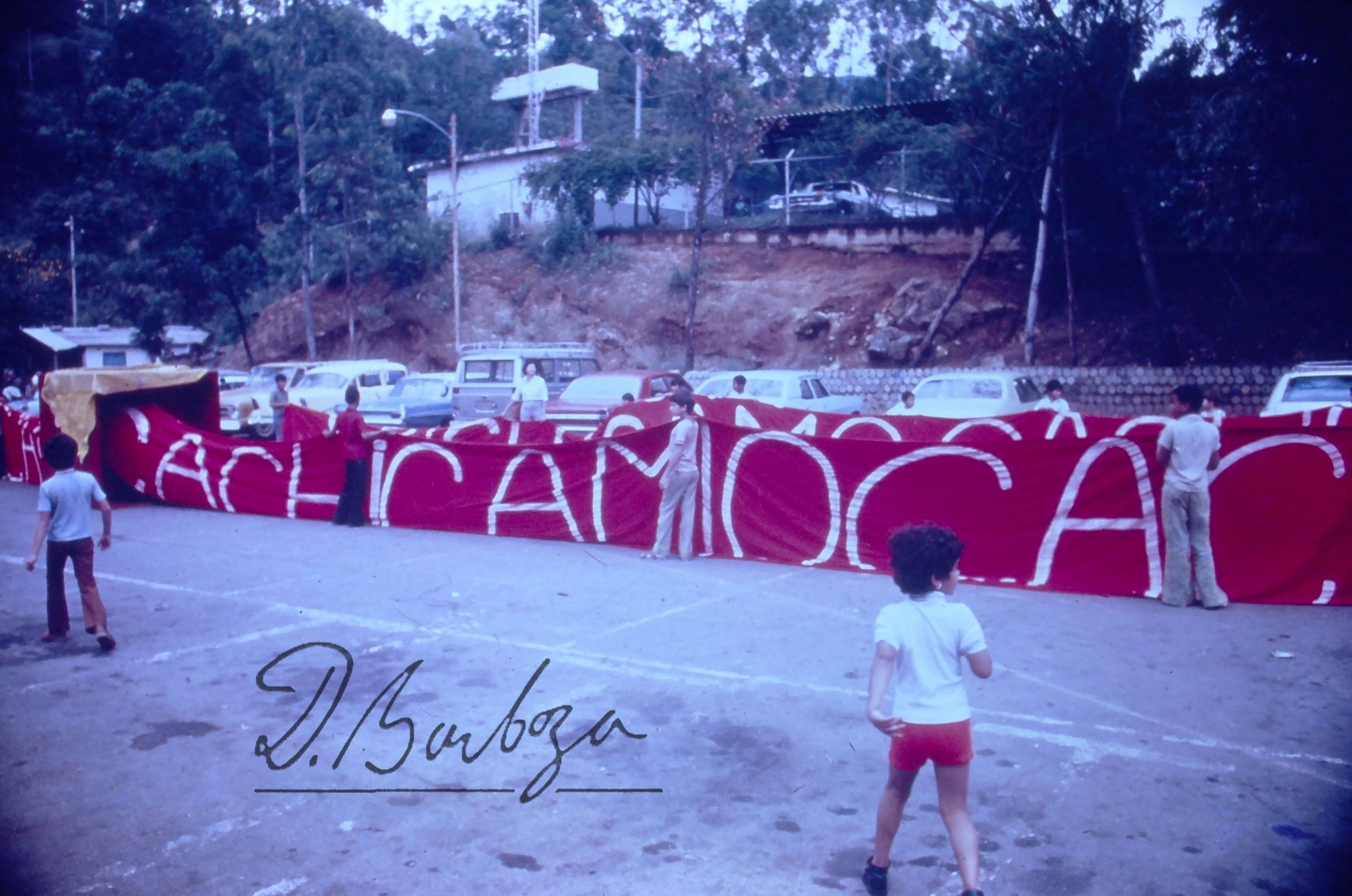

Such as washing clothes at a laundry, getting your hair done at the hairdresser’s, eating at a restaurant. Places like buses, factories and parking lots, those were the scenarios where Diego intruded. One of the most relevant cases is Expresiones en la lavandería [Expressions at a Laundry] (1972), in which he makes use of a public but inside space that is very popular in European cities. Thus, in this expression (carried out in London) the group bursted into an everyday situation, with a festive spirit totally alien to the context, breaking away from the established logic by presenting a different possibility within a routine space.

In 1970s Venezuela, many artists experimented around public space, however, not everyone sustained an interest in the subject, transforming their searches into more contemplative results. In Barboza's work, did this approach to the public remain present?

If we were to talk about some kind of transformation in Diego's work, it would be regarding the different ways of expression in which the actions and their images were manifested. That is, each of the actions includes a set of sketches, graphs, and outlines. After the action was done, there were collages, interventions of the photographs, the paintings, all belonging to the same universe of the event. His training naturally led him to traditional techniques such as drawing, watercolor, Indian ink, and chalk.

And did he follow any particular logic in this process?

Diego worked from a project structure. Prior to the actions, he envisioned how they would unfold in space and draw them; in these graphs you get to see the meshes, some of the triggering elements, possible places, etc. After the sketches, came the staging, from where he obtained the photographs he would enhance in the interventions and collages. However, something very interesting would come later: the means of realizing and safeguarding the action now turned into a document.

In this archiving process, oral tradition gained an important weight for Barboza. But in these current times characterized by hyperinformation, these forms of communication appear to be at risk of disappearing. How do you think this intangible archive could be safeguarded and turned into memories for future generations?

Despite the ephemerality of his actions, Diego was concerned with leaving everything documented and explained. He insisted on this. He was persistent in the dissemination of his processes and propositions. He thought of the future, so after the actions, Diego designed posters and pedagogic brochures, through which he facilitated—to this day—the understanding of his work, making a recap or summary to explain to us what his events were all about, always in his own words.

In this way, he safeguarded his memory, in an object that links the artistic event with learning. In this case, the repetition of the information is important, so Diego's testimony is in writing. Written to be read and replicated. However, I believe that in order to understand the humanity of his actions, it is also important to access the history of those who were with him and who took part in building a collective, multiplying, transmissive voice.

And did he have a methodological way to convey these experiences?

There is one case in particular, in La célula [The Cell] (1976). This was a work with a strong political and communication component: "It was a sheet of paper that was delivered personally or via mail. It contained the reproduction of a human cell, numbered as an identity document" (in Barboza’s words), in which the idea of union and chain, very present throughout his work, is repeated. The person receiving the cell had to find the carrier of the previous and the subsequent number; finding these numbers was giving body to the work itself. At the same time, it established a connection with a communication system used by urban guerrillas.

On the other hand, the way these experiences were activated is also linked to the instructions and titles: express yourself, join us, or "please cut out the figures of King Kong and Marialionza"; it’s about understanding provocation as part of a playful methodology. But in contextualizing these strategies in their time, we notice that the issue of participation was recurring and fundamental, for the messages appearing on the press and in advertising materials, everything invited to 'do' through interaction with artistic elements. They were both containers of information and triggers of thought.

In cases like this work you mention, ¡Cuidado! ¡King Kong! [Danger! King Kong!] (1972), the pictorial and the conceptual gather around the festive, the bodily, and the ritualistic. How did these searches coexist in a personality like Barboza's?

Cultural syncretism was in vogue at the time. Diego's actions included elements of traditional folklore such as tobacco, music, and he even brought in food into the room. It wasn’t just the use of his images but also the staging of the hybrid cultural influences that make us Latin American, that are present in the universe built by Barboza.

Regarding Barboza's pedagogical career, do you remember his classroom dynamics?

I wasn't his student but I know his teacher skills, for he was a very generous being with his knowledge. Diego saw something and explained it, he read something and commented his thoughts on it. Everything about him was participation, action, construction, and even until the last moment, he encouraged reflection. For his part, with the students of his painting workshops, he worked hard to help them develop and mature artistic languages, the identity of their strokes, through traditional exercises such as still lifes and everyday objects, always under the idea of a guided freedom.

Barboza belonged to artists’ and creation groups, what place did collaborative processes have in the development of his oeuvre?

Diego was thinking from the collective. He enjoyed building together with other artists of his generation, he liked people, the street, the parties, and popular celebrations. Diego understood that by respecting and crafting such a diversity of festive expressions within the visual arts scene, new elements emerged bringing another dimension to the aesthetic experience. In addition, these actions were further scaled up with the participation of the general public and of his friends from the cultural scenery. In his processes he always tried to include others. Regarding the groups, Diego participated in many.

Therefore, just as there was a body of work made from the anonymity of the participants of his actions, there was also a collective construction made by artists known as 'Los Coincidentes' (a name given by Claudio Perna): Juan Loyola, Luis Villamizar, Yeni and Nan, Ángel Vivas Arias, Antonieta Sosa, and Perna himself, among many others. They would come together and create together, and tune in to an idea. But Diego also met with folk painters and artists, he was interested in building a common thought.

This is a very palpable idea in the action work From the School of Athens to the New School of Caracas (1980).

In this work, there is a temporary crossing between the need to know the classics and the possibility of reviewing them with an eye on the future. For this reason, it is based on the structure created by Rafael Sanzio in the Renaissance to establish a dialogue with the 'New School' of the Caracas of the eighties, which proposed through culture a whole new structure of thought.

This action was developed in many aspects: Each participant, invited and selected by Diego, assumed a character related to the ones present in the famous Renaissance painting being staged. In turn, the place takes on a special prominence, as it uses the neoclassical architecture of the Gallery of National Art to stroll around it, inhabit it, and bring it to life. In itself, it posed a clear but somewhat 'camouflaged' message: the institutionalization of new languages and the celebration of his 10 years of actions.

As a teacher, do you recover any strategies from Diego Barboza's pedagogy? What 'concepts' characterize your classroom?

I believe the instructions within a classroom should be clear in order to activate processes with an interdisciplinary methodology, always considering the phenomenological and the empirical. I also consider reviewing the materiality of the work from the idea, then the sketch, its development, its structuring, its documentation, as well as the subsequent reinvention of the materials. It is very important for me that students understand the importance of protecting the materials with the future in mind.

In the classroom, we also highlight artists’ substantial role within society and the arts system, as well as their contributions to local and world art history. We bring up the importance of creating a community among the students that allows for building actions from outside the classroom.

Beyond art, how are you linked to Diego Barboza today?

In every possible way. I feel part of his logic, I’m a safeguard for his structure of thought turned into artwork. In a way, all of us who joined Diego's processes are a piece of his living work, informing from different fields Barboza's quests for integration as a society.