Language and Existence

03/07/2022

The artistic work of Antonieta Sosa has the dialogic mode—expressed or implied—among its frequent resources, with a circulation and dynamic exchange of ideas through which two or more beings acknowledge, identify or confront each other. It is a very personal method towards the progressive constitution of a work and, more generally, a knowledge-building process.

This text is an approximation to the work of Venezuelan artist Antonieta Sosa. Among the various fields that make up her trajectory, we choose her consistent bond with formative processes through art, in which she has made aware—for herself and for others—some fundamental relationships: art as introspection, as a vital experience, as transformative self-reflection. But also art as an alterity, as a personal mode of transmission, advocacy, and communication to make you think, make you feel, make you free.

In the art world, concepts such as "education" or "didactic interest" can be viewed with respect, but also, and conversely, with suspicion and even with a pejorative tinge when talking about "didactism." For creators such as Lygia Clark, Luis Camnitzer, Claudio Perna, Gego, Diego Barboza, Pedro Terán, Theowald D'Arago, and very sensitively for Antonieta Sosa, however, education as a topic is directly—consciously, fervently, and unashamedly—entwined with their own artistic production.

An integral and yet very personal vision of the creation processes makes her work an art-life proposition: art is in her a vital and lively experience that allows her to move towards a transformation of herself. It is then, first and foremost, an inward journey: a follow-up in time. And this experience of self-tracking gives her a basis for going outwards, forging with her body actions and with her teaching work a sensible encounter with her fellows—with this other who is never an alien to her—so that they go beyond their usual gaze, so that they extend their thought to what is not-yet-known, to the unexpected even of themselves.1

On educare/educire

So there is, on the one hand, Antonieta with Antonieta: moving through her becoming, from the past to the present of each new body action. On the other hand, there is her in her bond with the other: stimulating people to travel across in their own duration, from the present of contact in the educational space to the future of the realization of their own art project as a life project. She invites them to learn the technical resources, to achieve structure, to discover themselves in their thought, and, in a special way, to connect with their sensoriality, also learning to de-structure, to open themselves up to the game, to the not previously articulated, and even to situations that come by chance. She knows that educare/educire goes beyond guiding and offering new knowledge: it is essentially about extracting from others the most substantial of themselves.2

In these ways, far from exalting and mythologizing the artist or the object produced, a vocation and a fundamental awareness towards the other is involved: a human, a fellow being who needs growth to become what it is, to find itself. Thus, the other who perceives, who sees and feels, who changes in the learning process, is the irreplaceable for whom in the work of this artist, which closely complements the what fors that move her: the search, for example, of a more integral art that can transmit contemporary languages while mobilizing the progressive construction of a personal existence—both theirs and her own.

There is something remarkable—which can occur in her consciously or not, voluntarily or not—and it is that she transmits her own sincerity/need of being to the other. She does not impose an ought to be from the outside nor a way that copies another, the one that comes before or above and is recognized as a master. What she wants to stimulate is rather each being’s genuine need, the concerns and reasons for each one’s will to create. It is not about conveying something circumstantial, artificial or external but a much more essential—although sometimes elusive—"what for." What do I do what I do for? And for whom: for herself, the artist, and for the other—both the one who is akin and also the one who is different.

Antonieta Sosa has exercised an inspiring mastership, transforming the other she cares for: aesthetically and ethically. She explores for her young students the diverse world—that of external reality, that of the psyche, that of the languages of art. Maintaining the expressiveness of her being a person, of her being an artist, and the powerful peculiarity of her work, she refuses however to encourage student followers and does not believe in maternalism in the field of teaching.3

The Diversity of the Recipients

The other is also the others: a diversity, since genuine artistic processes are capable of attracting and inciting very different people, from children and teenagers in creativity workshops, through university art students, other artists and different audiences. And they are even capable of making believe an almost-disbeliever, a cautious thinker before this kind of avant-garde, as we could see in the turn that the American philosopher Stanley Cavell took—a turn in his approach to a type of artistic medium that he acknowledged not to love—when he came across Antonieta’s work at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas, during the Cas(A)nto exhibition, in 1998. Cavell had been invited to give the seminar “El mundo por las cosas” [The World for Things] when he coincided with this exhibition.

After admitting that many philosophers are not open to the art that is contemporary to them, nor to having dealt with it,4 and after acknowledging that even many contemporary philosophers also have conventional tastes, Cavell told me, moved:

"I pray to remain open to individual achievements by individuals who come from God knows where, with who knows what preparation, under who knows what appearance. My recent encounter here in Caracas with the work of Antonieta Sosa I consider a testimony of a continuous willingness to look again and to rethink. But I still insist: if I am attracted to these works it may be because they make some unprecedented connection with the entire history of human works, and because I find a new intelligence in them."5

Dialogue

H.G.Gadamer will refer to "the dialogue that we are." For him, dialogue "is language realized."6 A good dialogue is a back-and-forth where the participants grow together the ideas that arise, which are intertwined as questions, answers, and re-questions, and which could even transform the premises that each participant originally brought. Language is constituted in this exchange between the dialoguers, as something that no longer belongs to the sphere of the me but to the sphere of the we.

The artistic work of Antonieta Sosa has the dialogic mode—expressed or implied—among its frequent resources, with a circulation and dynamic exchange of ideas through which two or more beings acknowledge, identify or confront each other. It is a very personal method towards the progressive constitution of a work and, more generally, a knowledge-building process. It is an action with the other and also something especially valuable: a support against loneliness. Attentive to the idea that art can also be a healing element—something that is not alien to her permanent interest in psychology—the idea of dialogue and interlocution in Sosa also seems like a strong position against isolation and another way of defending herself in her acknowledged and assumed vulnerability. But it is also a way of giving others strength for their growth and that of their work, to face the frequent loneliness in that complex stage of young people in training. It seems appropriate to recall here the phrase of the French philosopher Jean Francois Lyotard: "In interlocution, one says to the other: do not leave me alone."7

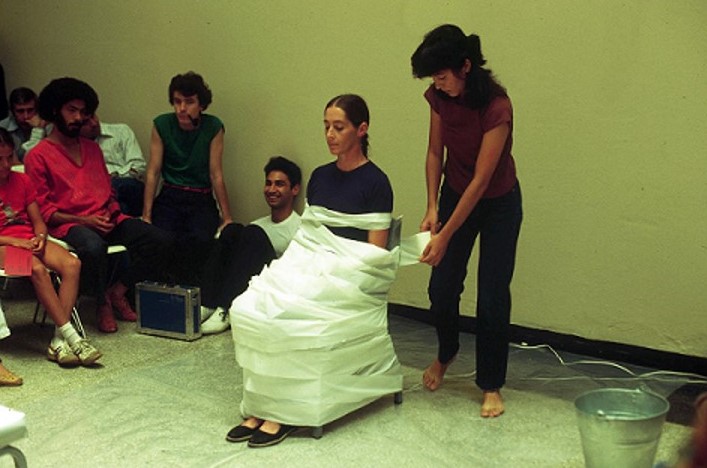

In Sosa's career, several situations from different times have dialogue as their axis, such as when she presented in 1980 Conversación con baño de agua tibia [Conversation with a Warm Bath] at the Galería de Arte Nacional in Caracas. A double encounter takes place in this work: a direct one with the audience through her body action, and another verbal, previously recorded one, between the musician Alfredo Del Mónaco and the conceptual artist Héctor Fuenmayor. In 1998, during the exhibition Cas(A)nto at the Museo de Bellas Artes (MBA), she presented the installation Salón de té [Tea Room], which is based on her 1983 work titled Antonieta vs. Antonieta. In Salón de té, two silhouette images of the artist appear on the wall, gesturing a dialogue between them8. Dialoguing with herself has been, by the way, a constant habit in her life, as could also be seen in her Cuarto de diarios [Diary Room] (she keeps life diaries, work diaries and dream journals). Later, in the collective exhibition Fragmento y Universo (CorpBanca, Caracas, 2002) she presented the installation Conversación #3, con María Elena Ramos [Conversation #3, with María Elena Ramos], in which she partially reproduced the real dialogue that we had held in her house-studio five years earlier, during the preparation of her solo show at the MBA. Here she incorporates a different kind of dialogue, this time between the artist and the critic as that other who investigates, who inquiries into relevant or unknown aspects of her life and work.

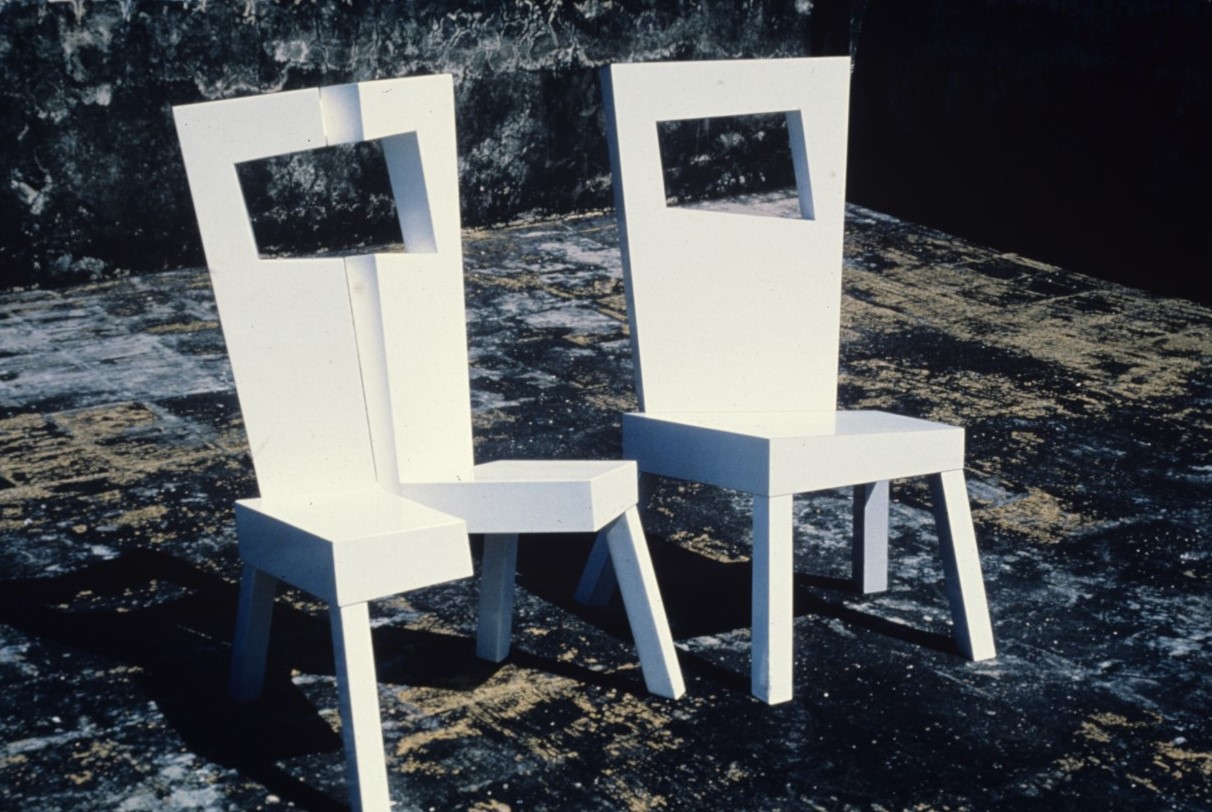

More broadly, the need for dialoguing with others—in more direct or indirect ways, and in different formats—runs through her creativity over the years. We can sense this, for example, in her passion since the late sixties for the creation and use of chairs, which generate very personal aesthetic structures that are extensions of the body and, thus, also a support for potential dialoguers—real or imaginary. We can also see this in her interaction with her art students. In this sense, although she did not carry out specific works in which she dialogued with students, we could imagine them now, knowing that she kept a lively dialogue with them.9 And there is an even more indirect dialogical mode, when she leaves behind an art that proposes reflections and asks questions but does not always expect—or seek, or reach—answers, although already in that very questioning she gives the other headspace for answering, to continue asking and, above all, questioning, thus triggering a dialogue in time, a more intimate one, with oneself.

Breakings, Noises, and Dissonances

Antonieta Sosa admits that there is always a play between order and chaos in her. If this dialogic mode turns out as a positive process—work-forming, capable of ordering and structuring thought—there is also another rather disruptive and apparently de-structuring trait.10 She is also akin to dissonances and cracks, this is visible in several areas: in her need to express gaps and insufficiencies of traditional academic methods, in her need to respond and protest in a more social and political sphere, in her own ways of self-protection against her fears and in the face of complex situations in the family environment that marked her childhood.11

Different ruptures have been present in her work. Let us recall, for example, the demolition of her Platforma II in 1969, which she herself carried out shortly before it was to be shown at the Ateneo de Caracas. At the close of the exhibition, Sosa destroys the platform as a political protest in what we could call, without paradox, a constructive destruction because with this action, to which she invited the public to participate, she sought to create awareness, to transmit sense. More generally in her career, she needs to break prejudices, to dismantle schemes, but also to weaken the damages, even at the cost of breaking something lovingly made by herself before, as in this happening with which she tried to avoid—in a time of dictatorship in Brazil—the participation of Venezuelan artists in the Bienal de São Paulo.

In 1981, during the series of events Acciones frente a la plaza [Actions in Front of the Plaza], organized by Fundarte at the Gobernación del Distrito Federal, she produced a rupture of glasses in her performance ¿Y por qué no? [And Why Not?], a body action of a more intimate motivation, full of breaking noises and glass chips. That same year, she made Situación titulada casa [Situation Called Home], an installation at the Museo de Bellas Artes, with which she participated in the 1st Bienal Nacional de Artes Visuales. It was a rancho12 with visible bricks, covered on its upper edges with broken glasses, as can be seen in the reality of many housings in Caracas. Both in her performance ¿Y por qué no? as in her Situación titulada casa, she radicalized with gestures and forms the confrontation with her own fears—some more intimate, some more urban—all of them affecting the psychic life and social bonds of citizens.13

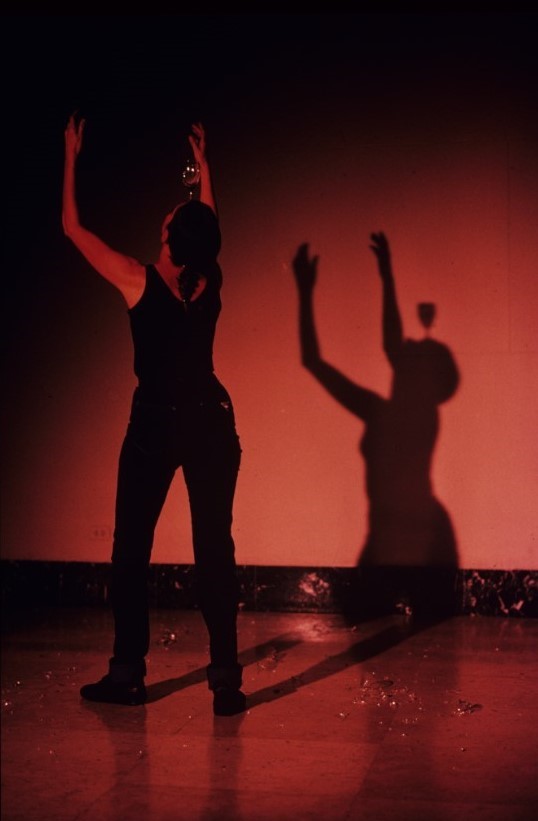

In 1985, she presented the event Del cuerpo al vacío [From the Body to the Void], an inquiry into identity carried out in three areas of the Galería de Arte Nacional at subsequent moments.14 On the second stage —Pereza [Sloth]— she made an integrated synthesis of some of her languages, going from the abstract two-dimensional work hanging on the wall and characterized by grids of painted flat forms (Finito [Finite], Infinito [Infinite], and Estable-Inestable [Stable-Unstable] were three works related to geometric modernity created by her in 1965), leading to a three-dimensional scaffolding, an object of the real and working world of the construction workers, that in this case became an artistic support and a privileged environment for moving through the metaphorical path of the search for herself.

The animal we call the sloth was there the basis and inspiration for rhythm and movement. Thus, the sloth comes out as a sign to suggest that learning—about otherness and about oneself—takes a slow time, a long and silent surrender, a noble "sloth" that allows to appreciate the value of slowness in a world stressed by hyperkinesia. These modes also allowed her to appropriate a certain—even symbolic—purity of sloth, in the sense of something unpolluted, neither by the haste of achievement nor by the hurries imposed by others, nor by the need for accumulation, which are replaced here by the search for dispossession in a slow transit that sharpened her perception. Knowing the artist, all this revealed what we could call, without paradox, her urgency of slowness.

In this work, the experience of the voice resonators, which she had learned from the theatrical techniques of Jerzy Grotowski during her dance-theater studies and her body training in the Contradanza group, allowed her to activate with heartbreaking sounds the visceral calls of an abysmal and organic world, animal and human at once.15 Arising from unrecognizable zones, that voice—trill, muffled scream or reverse shriek—is located inside, in the depths of her body that moves across the scaffolding. But at the same time, she is opening an exit from herself in the search for radical contact with others, shocking them, spreading a part of what one is and what one has been and learned in the journey of life and language, and activating them through her own multiple experiences. She extended herself from visuality to cenesthesia, from the abstract plane to the organic experience of the body, from the pictorial image to the reality of the accessible space.

Fractures and demolitions also play an important part in Antonieta's relationship with her young students, when she educates in and for dissonance, incorporating differences, cuts, and detours to incite them, but more simply, to stimulate awareness towards the natural incompleteness of human life, towards the noises that come from outside or from the psyche itself, proposing them as topics for reflection, on one's own sensibility and on the realities of our time, and showing them as a disturbing—yet fundamental—source of creation at any age.

Art, Life, Education, Cure

The relationship between art and life, and the idea that life is more important than art had been principles of the conceptual, bodily, and behavioral avant-garde, but they have not always materialized in the artists’ works. On the contrary, many turned out to be excessively hermetic or cerebral. Antonieta Sosa not only took this ideal seriously but materialized it into actions, objects, and situations over the years.

Creating, as well as educating through art, have also been ways for her to encourage life and health, stimulating the "cure" of the artist—both hers, who forms and is formed, and of those receiving training. Her students perform breathing and gestural exercises in class, imagining the acts of being born, crawling, sliding, hitting the wall, trying to stand and falling several times until they make it. And it has been relevant for her to encourage them to work through the autobiographical exercise, being aware of the importance that self-knowledge has in the artist's path.

Her art is, thus, both a matter of language—visual, bodily, and verbal—and an existential proposition. Being’s existence in its reality: acting, occurring, failing and rising, strengthening, struggling with its fears, healing. It is the being living, the being-being in its duration. French philosopher Henri Bergson had already pointed out that duration is a “synthesis” between a multiplicity of successive states of consciousness, and the unity which binds them together.16 And that "there is one reality, at least, which we all seize from within, by intuition and not by simple analysis. It is our own personality in its flowing through time—our self which endures."17

In the exhibition Cas(A)nto (MBA, 1998), where she reconstructed areas of her real house inside the museum, she shared with the public revealing facets of this being-being in time, of this intensely focused and confessedly vulnerable person and artist. There is the presence of the intimate, of the minimal, of the poor, of dust, of the daily life of her home that is also her workshop. There is awareness of the environment, and as in her installation Las hormigas [The Ants], there is respect for the small animals that move around her home, which she not only peacefully lets be but even brings them into her act of respectful creation. There is her lucid awareness of space—the real, the imaginary, the possible. And there is her stark awareness of the passing time, as in the photographic series Mi piel [My Skin], or in the successive shots of her face over the years, presented in small jars in her Autorretrato [Self-Portrait]; or as in the installation El polvo de mi cuarto [The dust of my room].18

There is the video A través de mis sillas [Through my Chairs] and some of her object-chairs are present in the room (Silla cubista cerrada [Closed Cubist Chair], 1969; Silla con pirámide de pelos [Chair with Hair Pyramid], 1970; Silla con seis patas [Chair with Six Legs], 1978; Dos sillas y media [Two and a Half Chairs], 1981; Silla positivo-negativo [Positive-negative chair], 1981; Silla del cuerpo [Body Chair], 1989; Silla de la razón [Reason Chair], 1998, among others). They are so evocative of previous body events—in which the artist or the audiences have used them as language elements and as basis and rest for the bodies—that they become already marked objects, which carry in themselves the very personal and unique imprint of the artist. Chairs as sensitive objects and, at the same time, already sensibly autobiographical.

Thus, in the course of her work we find solitary creation and a need for conversation; aesthetics and ethics, body and concept, idea and movement, instant and duration. An integrality was built upon her work, with the happy inclusion of various languages that she manages to fit fluidly in the space of the installation and in the time of the performance. Marked by visual and bodily research and phonetic processes, by her studies of psychology, dance, and theater; an abstract painter who steps into the three-dimensionality of the world—including living beings, objects, and, especially, her own body. She has been creating situations—conceptual and corporal, abstract and phenomenic at the same time—in processes that allude both to the history of modern and contemporary art and to her own journey: the history of an art of her own, encouraging others to create their own stories.

The construction of language and the liveliness of existence are strong realities in the work of Antonieta Sosa. These two words, which have entitled this short essay, are a conceptual pairing that defines her, and that takes place in her processes of introspection and creation, as well as in her passionate dedication to knowledge and the growth of others.19