La Escuela___: How or when did you meet Antonieta Sosa?

The Studio Is Inside Your Head

09/08/2022

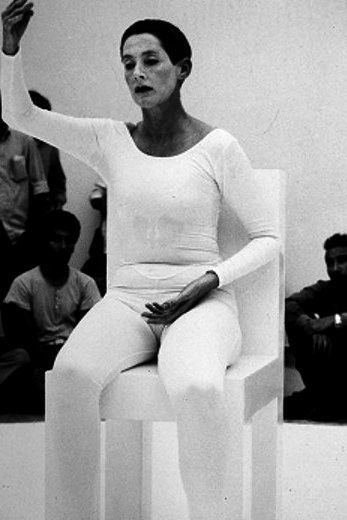

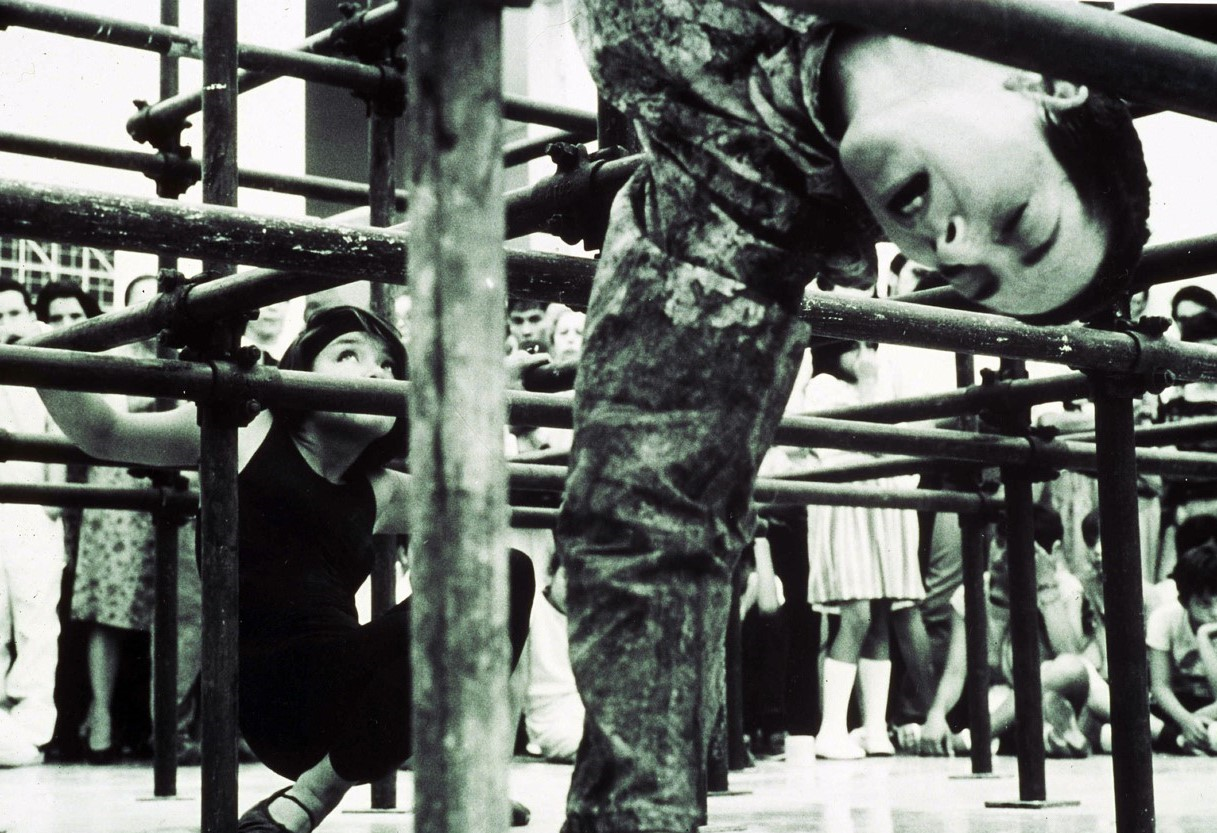

Antonieta Sosa (1940, Venezuelan, New York) is a conceptual artist who addressed pedagogy as a social, ethical, and political action through her artistic practice, from a particular sensibility for the poetic and performative possibilities of space. With a special interest in the body as well as its expressions, languages, and anthropometric interrelationships, Sosa is deemed as one of Venezuela’s great educationists of contemporary art. Her work is an influence for many artists of younger generations, both for her compelling oeuvre and the depth of her teachings. Among her students is Nayari Castillo (Caracas, 1977) an artist who develops her work across the fields of public art, installation, and research, with interventions that link history, space and time, and with a special interest in perceptual experiments and interactions. From her current residence in Graz, Austria, she talks to La Escuela___ to let us into the universe shared with her lifelong teacher.

Nayarí Castillo: I have been with Antonieta all my life. When I was a child, she was my Art teacher in elementary school; she was too in my teens, in the Arte Libre Workshops of the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas (MBA). Later on, when I went to study art at the Armando Reverón Institute (IUESAPAR), she was my professor of Artistic Language, and even afterwards, when I was studying at the MFA. I mean, I have always been her student, it's a lifelong relationship.

We are curious to know about Antonieta Sosa's pedagogical processes in elementary school and then as a university professor, what were they like at one stage and the other?

As a child, I remember activities related to the body and its expression; also many drawing exercises. In college, on the other hand, the weight of the ideas and the installation mattered much more; the bodily was always present, though, but more in the sense of spatiality and the structuring of space from the physicality of the elements. Activities that were key to my learning and that now, as a teacher, have become exercises.

Could you share some of them with us?

There is one that is fundamental to me; in fact, I use it on a recurring basis in my pedagogical practice. It consists of explaining what the installation is and providing a broad referential landscape, then delivering a piece of paper to the students with which they must make an installation in the room. You cannot draw nor cut, because you have to try to use only the sheet, but you can do other things, like ripping. That is an exercise that has impacted my students very much because of the challenge it entails.

You have known these two facets of Antonieta throughout your life, do you find differences between the artist and the teacher?

I think Antonieta did a lot of her art through teaching. She was an educationist with a devotion for process and that was present in all her phases. So I don't think there is a difference between the artist and the educator, because everything she experimented with in her personal work, she would try to translate it into education.

One thing Antonieta always tried to inculcate was doubt: not believing anything you were told; that also included comments about your work, because if a lot of people like your work, that might mean you are operating with simple codes (laughs). So it is a possibility that your work might not appeal to everyone, might not be understood by the masses, and that is not a bad thing.

That is an ethic of teaching, working, and learning. What other ideas do you feel traversed her practices?

Antonieta had an ethical practice that permeated the academic sphere, which is the idea that the studio is in your head, and no one can take that away from you. She encouraged you to cultivate inner strength, to be present, to understand that your personal history gives you structure. She also always called for not selling your soul to capitalism—Antonieta hardly ever handed over artworks for sale and was very careful of who said her work was important and whom she believed. It was a way of being critical, of placing yourself outside the work to make room for distance and to understand it.

In a text called El taller del lenguaje plástico (The Artistic Language Workshop), Antonieta makes constant references to introspection, autobiography, self-discovery... How were these concepts handled in the workshop?

There was room to explore fears, and even things you didn't like were an essential part of what filled the artwork. Autobiography, meditation, introspection, were dynamics that were always present. Those who were her students learned techniques based on the idea that the studio is inside, and that creates psychological spaces that allow us to do constant work. That is why she also talked about a certain ‘pollution’ that happens once you are an artist, because then you never stop being one, you will constantly be working.

In situations such as Del cuerpo al vacío (From the Body to the Void) (1985), Antonieta Sosa establishes a reference-homage to Oskar Schlemmer, an important name for the Bauhaus school. As a student of Antonieta at IUESAPAR and later on of the Bauhaus, do you find connections between your training places?

Of course! Antonieta was a very inclusive woman regarding knowledge: if you knew about philosophy or history, or if you worked with your dreams or believed in Jungian analysis, all this could be poured into the work. On the other hand, Bauhaus is a very particular school that works with projects, and which works in a similar way as the Armando Reverón Institute did, or as perhaps the Caracas art scene functioned at the time—we are talking about the late 1990s and early 2000s. We worked in teams a lot, we helped each other constantly, and that was a very good basis for what came later at the Bauhaus, which is a system where everyone has a personal project. My study program was called Public Space and New Artistic Strategies, and it was about solving urban problems. It was a process that required the same versatility as the conditions in Venezuela; that is, we had to help each other because not everyone had tools or resources, so we all had to use everybody's tools and capabilities.

So, while the studio is in the head, we are also 'doers', we are constantly doing, even if they are intangible things. And I think that spirit was also in the Bauhaus school, the constant dialogue with others, because you need the knowledge of other actors to reach the best structuring of the idea, and I think this is something that has been there throughout all my processes, both in Venezuela and later.

Today, such collaborative models as well as collective practices have stepped into a prominent role within a certain landscape of art dynamics. What do you think this phenomenon is about?

I believe it has to do with many reasons, such as the versatility of information, its forms of distribution, which require a plural vision, and being in a collective facilitates the transmission of ideas. But I also think it has to do with the need to do more social work; I think it has to do with the social turn and everything the idea of making participatory and relational art implies, whose interaction spaces are usually very difficult to achieve on an individual scale, for they require getting involved with the environment, and this, in turn, requires collectivity and flexibility of gaze.

So, tell us, how did this interest in public space come about in your own practice?

I was awarded the first prize at the 63rd Arturo Michelena Salon in 2004; I was the first female artist and the first video artwork to win this recognition. And with the endowment I did something called Una cruzada por el videoarte en Venezuela (A Crusade for Video Art in Venezuela). Together with Gerardo Zavarce and Asdrúbal Colmenárez, we toured all over Venezuela with a projection machine talking about what video art was. In that process I learned a lot and understood that I was interested in talking to people, reaching out to others who had nothing to do with the white cube, and approaching them in other ways.

A long time later, I understood that my mother [Consuelo Mendez], as she was part of the muralist women of the seventies, had always been involved with public art. I also had a close relationship with Claudio Perna, who had a very particular way of understanding the public. So that relationship with the surroundings was always in me.

In contrast to traditional, commonly coercive education, artistic practice encourages the destabilization of thought patterns. Do you think traditional teaching is opposed to the ways of teaching art?

It is difficult for me to answer this, because I have always been a rebel who truly believes in alternative education systems but I have gone through all the traditional systems. My education has always been 'contemporary'. I always had very contemporary professors, not only Antonieta Sosa, also Carlos Zerpa, Nan González, Victor Hugo Irazábal. Not to mention my professors in Germany! I am an artist who has always been immersed in the contemporary discourse of spatiality.

And now as an educator, what concepts characterize your classroom?

The decolonial movement is very important for me. I teach at a school of architecture and I fervently work towards making my students aware of architects and artists from other latitudes, other genders, and other ways of thinking. To provide them with a multicultural, multifaceted, semantically plural worldview is almost more important for me than the spatial concepts I also address in class.

What can you tell us about your methodologies and processes?

I have many, but there is one in particular that interests me and which I use a lot both in public art and with my students. It is called 'on-site conversations'. It is about radically confronting the space where things are happening. To give you an example of how it works, I will tell you about a collaborative work called Field Standing (2017): We called on people to come meet at the Human Rights Square on Human Rights Day, to stand there for this cause.

We invited all the actors who make life in this park: drug addicts, dealers, punks, cultural agents, dancing old people, playing children, skateboarders; the police and the city council official too. We as artists invited all these people to make them dialogue. Of course, it was a fight, but it was also a very interesting process to see them dialogue until they realized that they had the same interests, and thus seeked to solve problems and evolve the space. This is a practice that we do a lot, to work with the problems of specific places on the site, and that is something I have adopted in my artistic and pedagogical practices.

You just described the basis of the Naked School: working in public space, approaching reality, dialoguing with it and learning from it; that is our main conviction. All these collaborative, relational, social, etc., practices have a formative aspect as their common ground, and when you work with different sectors and generate these dialogues, you are also doing an educational project for everyone.

For the past year, I have been doing research that has to do with structural events, in the sense that the social turn requires a lot of community work, and so the aesthetics are devoted more to this community process than to the structuring—that is, the incorporation of an object into space. So I'm investigating whether there are things you can deliver that don't require your care, events that trigger a spatial dynamic in public contexts, that are political enough and which allow people to act for themselves, without the artist having to 'marinate' the community.

Because I have the feeling that us artists who work in public space seem to end up becoming some kind of sociologists or human geographers, and I wonder if we can act as a middle space that creates structures that dialogue with the public but that don’t require your complete curation of the event, and instead allow people to do things themselves.

Of course, and also think about the idea that the work can go on without the artist, and then you can return to it, find it, and discover it; because certainly, although community projects can be open, the artist is usually still in a supervising or mediating position. It is interesting to be able to let go, too.

Public art has to do with detachment, because there are so many things you cannot control. But maybe now I'm requiring further detachment, which doesn't mean not being responsible for what you are introducing into space, but rather using that responsibility for generating other dynamics. That is why I'm thinking about where this performativity of space could be taken to, what is it that is introduced that changes the dynamics.

Would you reactivate or re-enact an Antonieta Sosa performance?

I think so... Surely not performatively because I am not a performer, but I believe in spatial performativity, so I would create triggers, whether semantic—as of word and narrative—or objectual, to reactivate Antonieta's work. But I would have to look at her artworks and choose one to see through which variant of my work would be that re-enactment.

Do you have a favorite work of Antonieta’s?

Of course I do, the Anto. This idea of measuring everything with Antonieta's body. Firstly, because I am the same height: 163 cm, and second, because it involves everything: If I have to think of something, calculate its physicality, that piece is like a default setting in my brain for thinking about the physical relationship with space. It is a very important work for Venezuela and for me as a spatial artist, because it is a bodily, physical relationship with what is around. I mean, I could calculate almost anything in antos (laughs), because, of course, it's my body too.

In your artistic work, space and the subject play an important role, beyond these topics, is there any conceptual relationship between Antonieta’s work and yours?

Of course, in the sense that the idea leads to the concatenation of many others, which creates spatial experiments. I don't know if it is a thematic or rather a methodological connection. But perhaps yes, in matters of accumulation, archiving, the observation of nature, a little different from the performative in art, but I believe that all my relationships with her—because she taught me for a long time—have to do with methodologies, with ways of doing art that have to do with experimentation and freedom.

Art requires you to be able to set your own rules and also to break them, as in a permanent game in which you make your rules, you do the experiment, it doesn't work? then you make other rules, another experiment, and you adapt. I deeply believe in what Antonieta posed: that the works are never finished; they will always have a change, never an absolute truth, and that is something I like. You must hesitate, you must think critically... It is a never-ending critical motion.