Art, Modernity and Pedagogy

10/04/2022

The notion of 'public art' understood as a transformative and revolutionary vehicle, at the service of society, is central to understanding his work—his life, as much as his production, is articulated by this precept.

David Alfaro Siqueiros (Chihuahua, Mexico, 1896 — Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1974) was radical in virtually every aspect of his life. As an artist, he revolutionized traditional methods using the techniques and tools of modernity. As a citizen, he conceived the figure of the 'civil artist' committed to the public function of art, activism and political action. As a theorist, he constantly reflected on artistic creation and teaching based on his own practical experiences, and even formulated his own model of the course of history and the future of humanity. Siqueiros was not characterized by a conciliatory tone, of "half measures" or "fair means," but by being a polemic agent and a fierce critic. In his case, it is impossible to separate art from politics, a conviction that earned him persecution, exile and imprisonment over the decades.

The notion of 'public art' understood as a transformative and revolutionary vehicle, at the service of society, is central to understanding his work—his life, as much as his production, is articulated by this precept. At the same time, each mural functioned not only as a space to develop collective work methodologies, but also fed the artist's theoretical apparatus based on concrete experiences.

To think today in the field of pedagogy and art education based on Siqueiros' works and ideas can be significant in two ways. In the first instance, it allows us to review his legacy and seek interpretations beyond the established narratives. At the same time, such reflection allows us to feed the interests and concerns of our own time, in which the pedagogical turn, artistic education, mediation, and technological devices have become central issues.

Art, Modernity and Technology

The history of Mexican mural painting is also the history of how to create large-scale works whose characteristics, impact, possibilities, composition, etc., are far from oil painting and easel paintings. After the Mexican Revolution, muralists had to experiment with different methodologies, techniques and materials to carry out this type of work. Some of them, such as Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, theorized about these procedures in relation to the becoming of art and society.

Rivera, for example, defended throughout his life the use of fresco as the ideal technique to create the "true" American art, where the knowledge of the native peoples of America was combined with the industrial possibilities of the United States. This technique, the muralist defended in his writings, would be the one that would allow the encounter of ancestral knowledge with modern glass and steel constructions.1

David Alfaro Siqueiros, on the other hand, postulated very early in his career the need to create artworks linked to the modern world and its possibilities. Since 1921, before painting any mural, he began to develop his stance on art techniques and materials. In his “Tres llamamientos de orientación actual a los pintores y escultores de la nueva generación americana” [Three Appeals of Timely Orientation to Painters and Sculptors of the New American Generation], one of the first Latin American avant-garde documents published from Barcelona in the magazine Vida Americana, he pointed out:

"Only art that finds its own elements in the environment that surrounds it is vital (...) we must be inspired by the tangible miracles of contemporary life, by the iron network of speed that embraces the earth, the ocean liners, the battleships, the marvelous flights that cross the skies, the tenebrous audacities of the submarine navigators."2

Although in his first murals, painted in the early twenties, the painter used traditional fresco, during the thirties his experiences in the cities of Los Angeles and New York led him to the use of eminently modern techniques and materials, such as automotive paint, the air gun, cinema and photography.

In short, Siqueiros set out to create a public and revolutionary art that took into account the technological changes of his time. The muralist emphasized that cinema and photography had transformed the human sensorium, equally transforming the creative sphere. The result was the articulation of a complex practical-theoretical device that led him to the notions of 'filmic plasticity' and 'polyangularity,' with which, as the critic Raquel Tibol pointed out, "he widened the channels of realism."3

With 'filmic plasticity,' Siqueiros posed the problem of how to build modern dynamism in painting with the help of the cinematographic device. ‘Polyangularity,' on the other hand, alludes to the multiple points of view that a mural can have, thanks to the possibilities of photography and film. In these notions, the spectator is no longer conceived as immobile or passive, but active and in movement, indispensable to give the final meaning to the work.4

To conceptualize the notion of 'montage' that he sought in his works, Siqueiros made use of the precepts of Russian filmmaker and theorist Sergei Eisenstein, whose aesthetic ideas definitively marked 20th century art. At the same time, as Anna Indych-López recently pointed out, the muralist took up techniques from the commercial and multitudinous productions of Hollywood, to the point that he came to conceive his own work on the scaffolding as that of a kind of director for the field of 'film-plasticism.'5

Muralism, Pedagogy and Collective Work

The scale of mural painting necessarily entails teamwork. In addition, Siqueiros defended collective practices and enterprises over individual ones, which he understood as a product of the modern western bourgeoisie. Mural painting, in this sense, was doubly collective: both for its elaboration and for its quality as public art for the masses.

In each large-format work, Siqueiros took advantage of the opportunity to create, in his own words, a "collective laboratory" of "pedagogical importance."6 That is, each one functioned as a space for formal and pedagogical experimentation where he sought the active participation of the people involved. In turn, each concrete experience fed his pictorial theories, which were then discussed again in the next large-scale production.

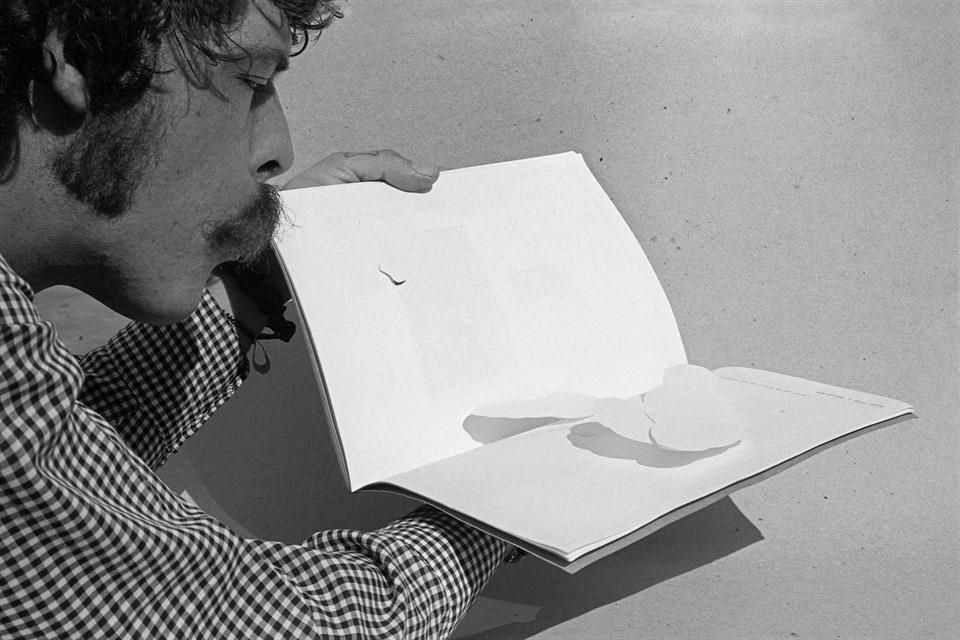

Although there are numerous documents that give an account of Siqueiros' collective and pedagogical processes,7 one of the most outstanding is Cómo se pinta un mural [How to Paint a Mural] (1951), which describes in detail the experience of creating a mural in the city of San Miguel de Allende, in the Mexican state of Guanajuato, during the 1940s.

In this writing, conceived as a practical-theoretical volume for the creation of a mural, the painter relates step by step the different facets of the production, which begin with "encouraging teamwork" and conclude with the supervision of the "photogenic value of the work." In between, there are numerous phases: photographing the practices to observe mistakes and save the documentation for future works; unraveling the geometric substructure of the building; familiarizing oneself with the space; discussing as a team the function and theme of the mural; deciding on the technique, materials and tools; building the scaffolding, etc.8

What is surprising at all times is Siqueiros' clarity about the artistic exercise as a collective and pedagogical practice; although always with the help of the director or "the most experienced person," the collaborators must come to their own conclusions about the work. As he states in the same volume: "the true teaching or learning of mural painting—simultaneously theoretical and practical—[happens] in the process of executing a work for the purposes of a specific task. The first and greatest teacher, the teacher of all, teacher even of the teacher, is the problem itself."9

Siqueiros was a fierce critic of the academy and of the conventional methods that, in many schools, continue to exist to this day. As he made clear in another of his texts:

"Our learning of the new technique and the teaching of the same to our disciples and collaborators will take place in the process of production and for production; theory and practice in a single impact. In this way we will put an end to the sterile didactic, verbalist teaching, applied by itinerant demagogues, which during the four hundred years of academicism has not been able to produce in the whole world a single transcendent value, and which continues to be the only method of professional and elementary teaching of art in Mexico, as in all other countries."10

The researcher Vera Castillo pointed out that a first moment where it is possible to glimpse the intertwining of art, pedagogy and politics in the life of the Mexican painter is in the student strike at the San Carlos Academy in Mexico City in 1911.11 As a teenager, Siqueiros was part of a revolt that sought to renew art education in Mexico. Decades later, the painter pointed out that in that movement the spirit of the "civil artist, the citizen artist who was going to replace the traditional bohemian, the artist for whom art is intimately linked to the problems of his country and his people"12 could already be glimpsed.

Later, as a teacher and director of large-scale works, the muralist had numerous opportunities to put his pedagogical laboratories into practice, although his educational practice was not limited to these circumstances. Siqueiros was a tireless promoter of artistic workshops and collective educational practices. In 1936, for example, he created the Experimental Workshop in New York City, a space marked by experimentation with techniques and materials. As is well known, it was there that Jackson Pollock would approach the formal experimentation that would later lead him to become the quintessential artist of USAmerican abstract expressionism.

Likewise, during the last years of his life, Siqueiros encouraged the creation of workshops-schools that promoted public art and teaching methods far removed from academicism, as in the case of La Tallera. Upon his death, the artist left a will so that his houses would be preserved as places for the dissemination of his works and ideas, to be used as centers of analysis and experimentation for future 'public art.' The work of his widow, Angélica Arenal, was key in accomplishing these tasks. Siqueiros also bequeathed a collection of paintings, sketches and engravings, as well as a photographic, newspaper and documentary archive that, along with his extensive library, can be consulted at the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros (SAPS) in Mexico City.13

During the seventies and eighties, after the painter's death, the SAPS became an international center of reflection, struggle and resistance, with a marked emphasis on the Latin American region. Thanks to the work of Angélica Arenal, Alberto Híjar and the militants gathered around the Taller de Arte e Ideología [Art and Ideology Workshop], conferences, film cycles, exhibitions, plays and workshops on literature and art history were organized. As Itala Schmeltz, the first director of the SAPS, relates:

"During the second half of the 1970s and the 1980s, the Sala was a fundamentally political art center. In those years of full dogmatic ecstasy, artists and intellectuals from many parts of the world gathered there to create what, in their own historical context, they conceived as a public art committed to social struggle. Art and drama, reflection and academic training, support and solidarity, even refuge and clandestinity, the Sala offered to those who still believed in the revolutions that marked Siqueiros' path; at the same time the battles were updated: now it was about Vietnam, Cuba, the coups d'état in South America, the defense against Yankee capitalism and the denouncement of its cultural imperialism. It was necessary to dig in to resist the black waters that filled the world with bubbles."14

There is no doubt that Siqueiros was an avant-garde artist (or an "eccentric" avant-gardist, to use the characterization coined by Mari Carmen Ramirez).15 He was also an artist that today we could call "global," possessing an internationalist spirit, interested in establishing support networks and international exchanges.

A defendant of liberties, a social fighter who participated in both the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, the muralist came to consider art forms other than the ones he himself produced as inappropriate, to the point of proclaiming, in his writing of the same name, that “No hay más ruta que la nuestra” [There is no other road than ours] (1945). It would be naive, in this sense, to idealize him and not to look at his life and work with a critical eye. His doctrinaire rhetoric, his exaltation of virility or his convinced Stalinism are questionable today.

At the same time, his permanent commitment to teaching, his emphasis on the importance of the native peoples of the Americas (beyond any "folklore" or "archaism"),16 his determination to produce "art forms for the broadest and most distant layers of the population,"17 his criticism of racism—present, for example, in the terrifying and current work Cain en los Estados Unidos [Cain in the United States] (1947)—his work as an artist committed to his time, and his tireless work as a social fighter, militant and activist, all of this challenges us today in a poignant manner.

Although he looked with great enthusiasm at technology and the processes of art in relation to modernity, Siqueiros also took a critical look at these phenomena. This is the case of Explosión en la ciudad [Explosion in the City] (1935), a painting in which a devastating explosion is observed in an urban environment. The explosion —with three-dimensional qualities due to the use of pyroxylin— functions as a skeptical, or at least ambivalent, view of modernity, progress and urban development. Likewise, his more experimental works and studies remind us of the importance of reflecting critically and consciously on the technologies of our time in relation to art, education and everyday life.

Artist of contrasts and radical convictions, painter of pyroxylin and air gun, revolutionary with rifle in hand, teacher and pedagogue, Siqueiros and his legacy are updated in the contemporary world as an inescapable reminder against rampant individualism, academicism, the rise of fascism in different parts of the globe, the uncritical use of technologies and the irrepressible irruption of the society of consumption in all aspects of our daily lives.