Claudio Perna: Documentation as Teaching

05/10/2023

by Rigel García

The Pernian praxis is today synonymous with the multidisciplinary, and the development of his vast photographic and conceptualist work was intertwined with his teaching practice [...] as well as with his research on photography and the creation of a public policy for the visual documentation of the country.

What role does the (re)cognition of one's own place play in the construction of knowledge? To register the space one is in, to take note of the changes, to match names with faces and place names with landscapes, to translate the abstraction of maps into a recognizable image, filled with life. To favor, ultimately, the possibility of writing history. This is the basis of documentation, an essential practice for any scientific discipline and yet, paradoxically, one of the most underestimated. The act of recording reality in images and data enables memory and contributes to sustaining systems of knowledge, teaching, and learning. On the basis of this premise, Claudio Perna (Milan, Italy, 1938 — Holguin, Cuba, 1997)1 was convinced that the visual and geographical conglomerate of Venezuela could constitute a classroom in itself—the country as a subject on and from itself. The access paths were those of experience, intertwined with the photographic practice and contact with the territory, since identity, in his words, was acquired in a space of concrete knowledge.

Perna's concerns regarding documentation articulated his thinking and his work. In both, archival methodologies support a plural and integrative universe of contexts that is full of connections between works and open to reflection on the production of knowledge. The Pernian praxis is today synonymous with the multidisciplinary, and the development of his vast photographic and conceptualist work was intertwined with his teaching practice—at the School of Geography of the Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV) and in his personal space, called Radar—as well as with his research on photography and the creation of a public policy for the visual documentation of the country.

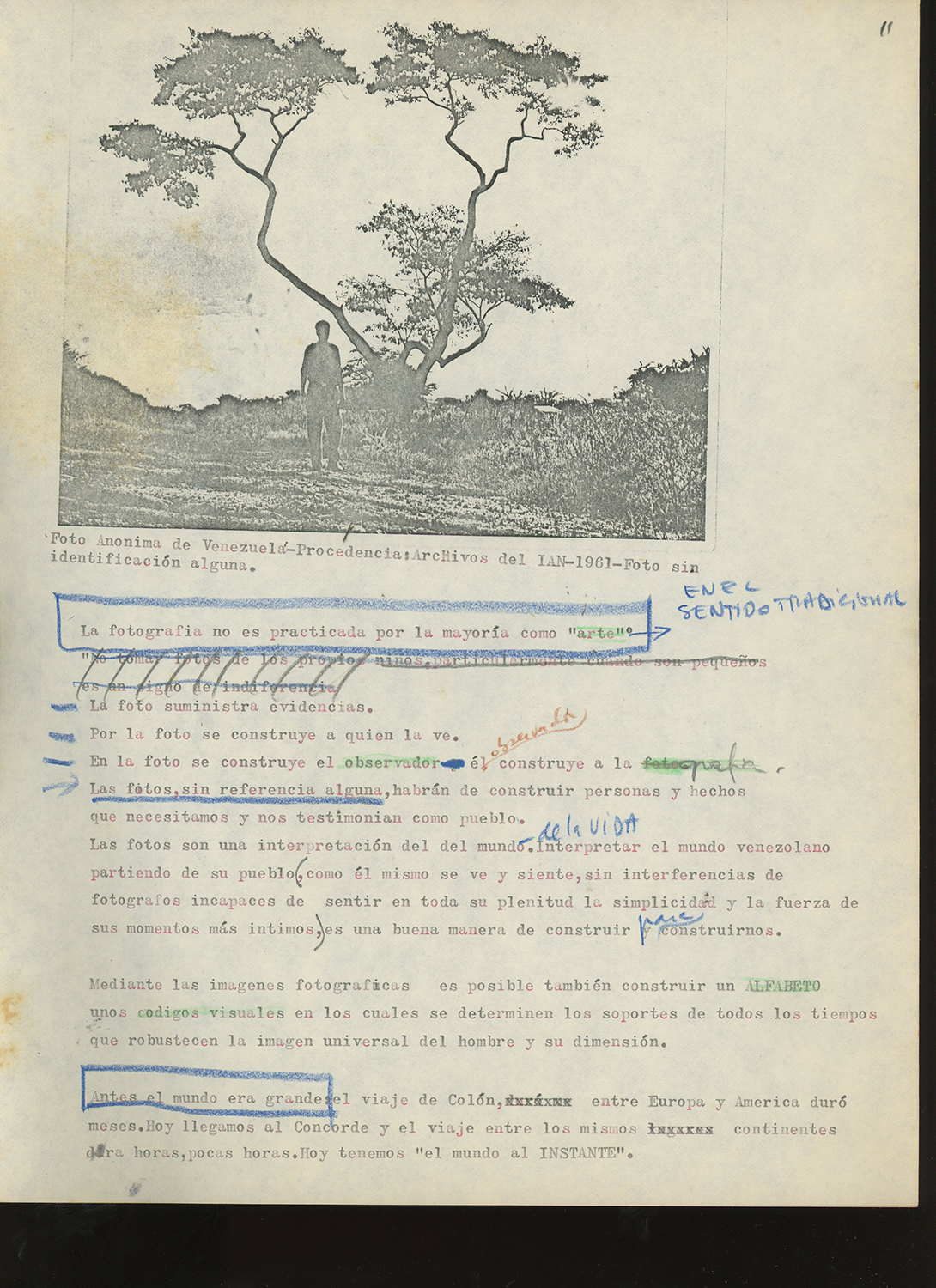

Perhaps these last two aspects are the least known within the artist's career. El ABC de la fotografía venezolana a favor del esclarecimiento colectivo (1979) deals precisely with those. It is a typewritten document with handwritten notes, images, and text fragments in which Perna gathered his experiences during the creation of the Division of Audiovisual Services at the Biblioteca Nacional de Venezuela,2 undertaken in 1975. The five volumes or folders in which it is organized include annotations on the history of national and international photography,3 the structure of the collections of the nascent unit, accounts of activities, models for identification cards, and internal regulations. It also includes quotes from photographers, artists, and theorists,4 photocopied clippings from publications, and extensive sections of his own reflections on the relationships between photography-communication-geography-history, the importance of documentation, and the role of anonymous photography, among others. From its first pages, El ABC... is a plea for the recovery of Venezuela's visual memory, deploring the lack of information to identify the available images (due to an absence of awareness regarding this practice), and denouncing the State’s lack of will to implement educational programs in this field.

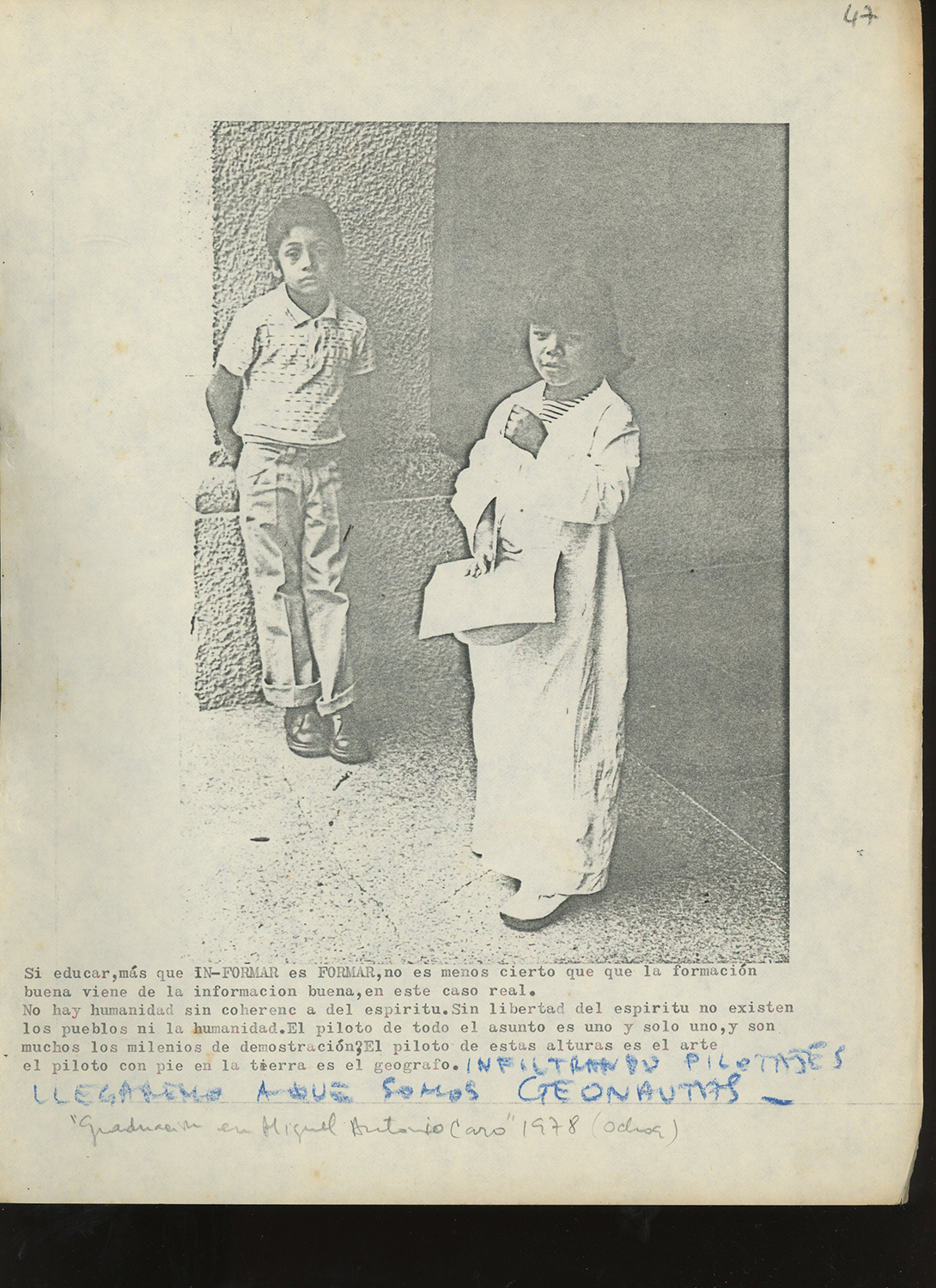

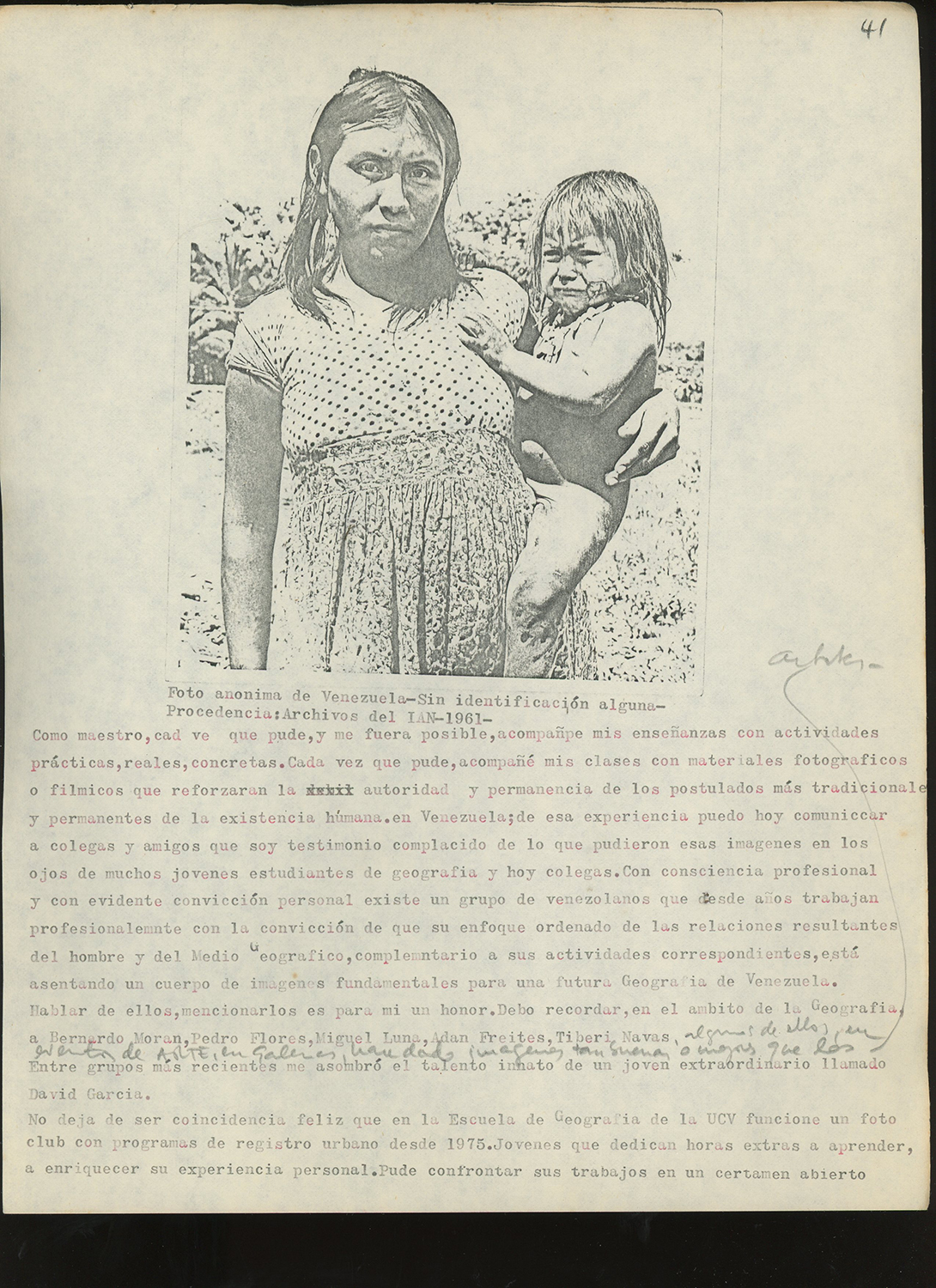

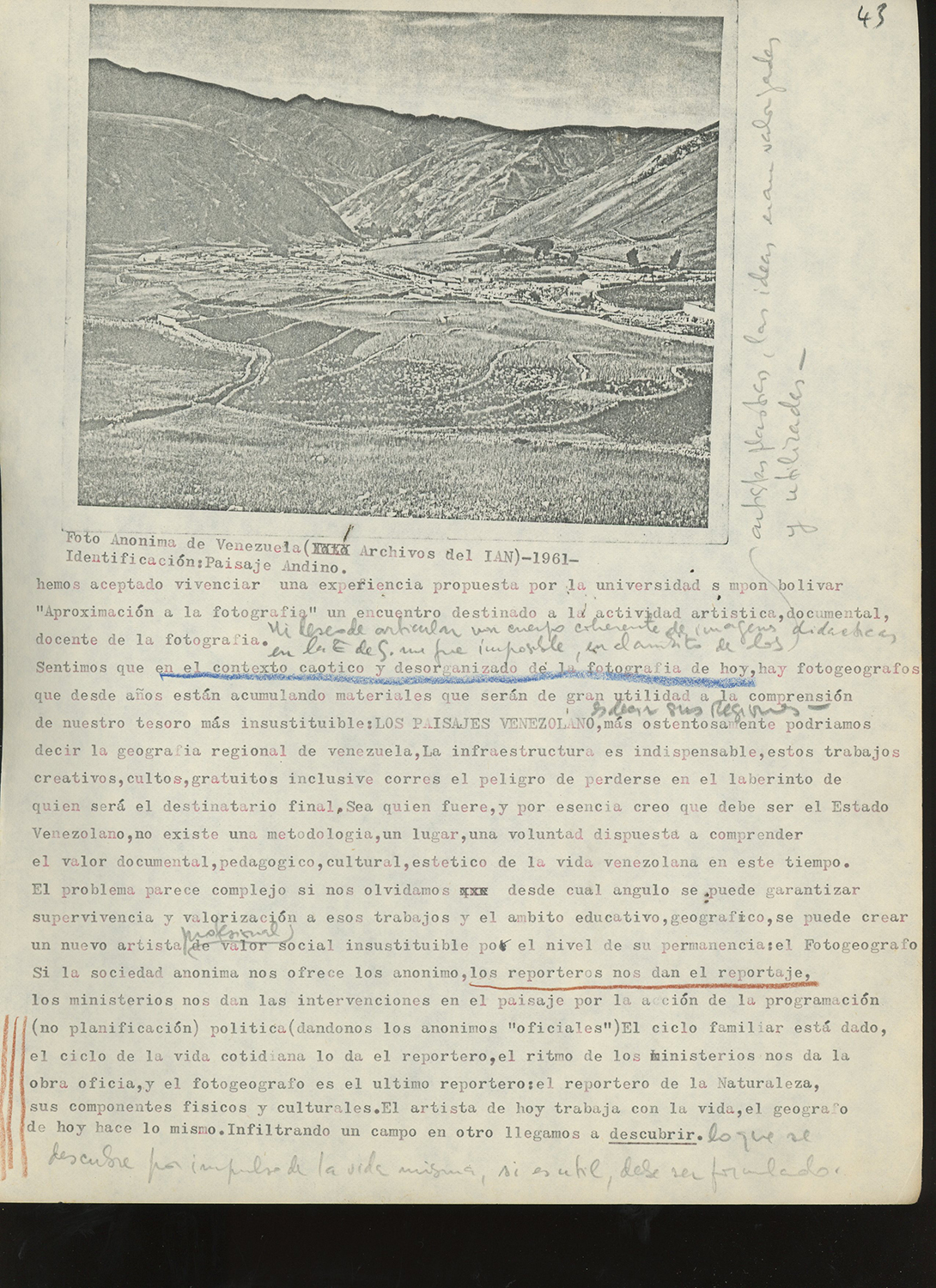

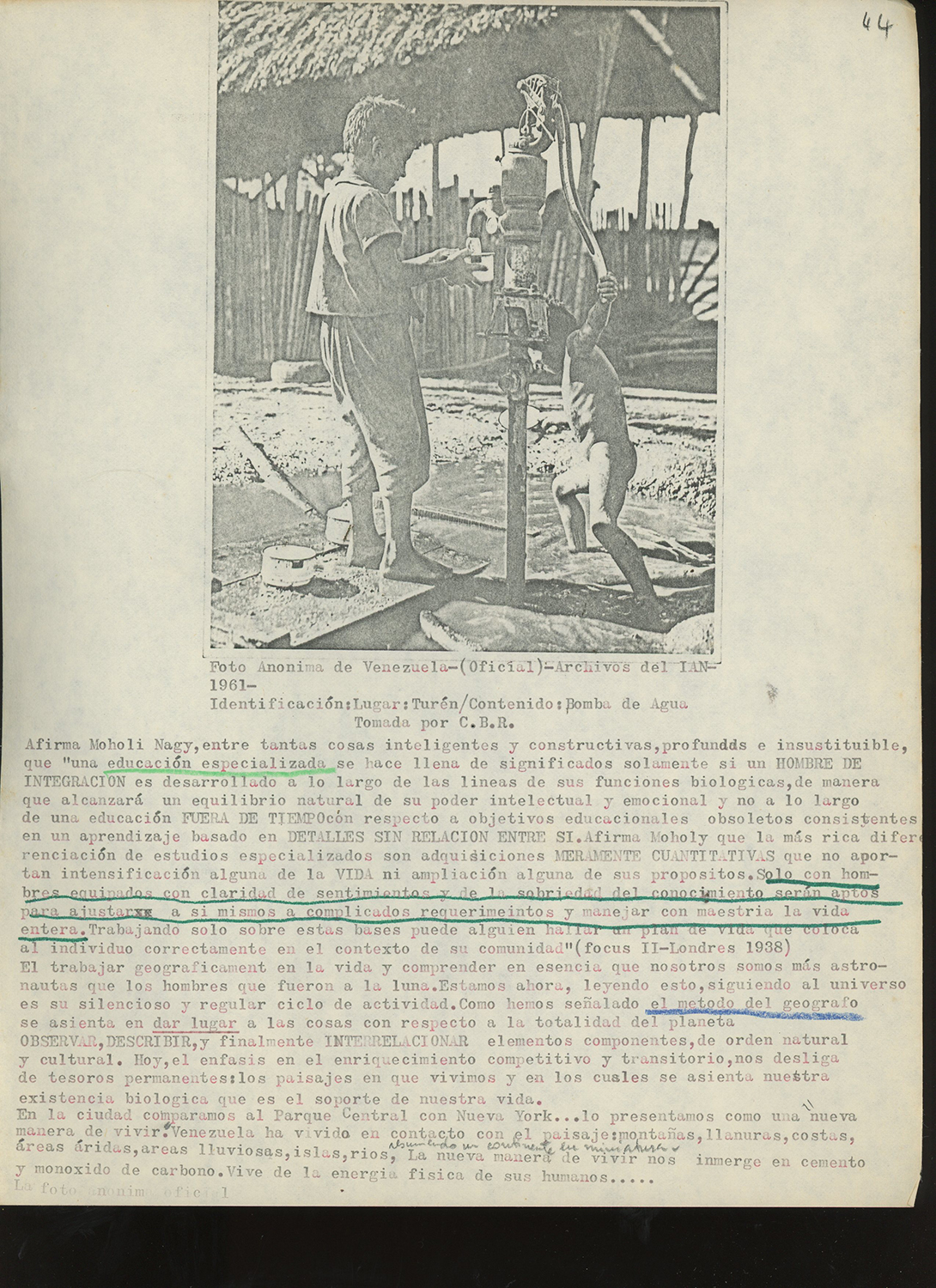

El ABC… affirmed itself as a "methodology of man for concrete solutions and against the ramblings of specialization without a collectively useful destination;"5 something that could be viewed as an organized documentation system linked to the task of educating the country. Along with illustrative images of the photographers and historical periods addressed, the visual portion of El ABC... is mainly composed of what Perna called "anonymous photographs"6 —images of landscapes, cities, and people from across Venezuela, mostly without author or identification, without artistic aspirations but with great documentary value. On one page, we read that documentary photography constitutes the "visual representation of a deeply felt moment,"7 a quality within everyone's reach, susceptible of being traced through family albums to state records. These records, made by unknown ministerial photographers, came from the Instituto Agrario Nacional (IAN) and served Perna to advocate for the potential of documentation as an (educational) foundation of knowledge about the country and, therefore, its identity. His main premise? The bond between image and place.

The Place of the Image

For Perna, the country included the landscapes as much as the people and, beyond that, existence itself. Anonymous photography was important because it was made in life, without the interferences or limitations of a pretended aesthetic discipline, which had, from the tradition of art history, only generated personalistic plots among artists and dispersed realizations, to the detriment of a collective search. He conceived photography in an intimate relationship with the context and nature, very much in tune with his training as a geographer.

Interested in the processes of communication, Perna assured, for example, that the images from the news should be placed over "city maps and country maps" to understand where and how they had occurred,8 which would, in turn, provide a context for understanding the process as opposed to the final news item. Underlying this is what he considered the formative (no longer in-formative) sense of the image. This relational perspective connected all factors in the equation, hence his clear protest against unidentified images, mutilated photos, and fragmented history. While Perna defended anonymous photography—popular, vernacular—as a spontaneous genre with a key documentary and aesthetic value in the construction of identity, at the same time, he advocated the dissemination of a method to identify images and the implementation of an infrastructure that would allow preserving such knowledge.9

Beyond its clear association with the practices of conceptualism, the idea of process is one of the foundations of documentation, as a discipline that allows recalling different moments of a given situation. Throughout El ABC... Perna insists on the need to gather visual information about the country and its people to account for historical, geographical, urban, and cultural changes. Processual awareness would become the methodological basis of his reflections in this document, resorting to procedures borrowed from geography in his quest of documenting in order to know a land or an experience, taking real data—in this case, provided by the photographic image—as a basis. He argued,

"If educating is more about FORMING than IN-FORMING, it is no less true that a good formation comes from good information, in this case, real." [10]

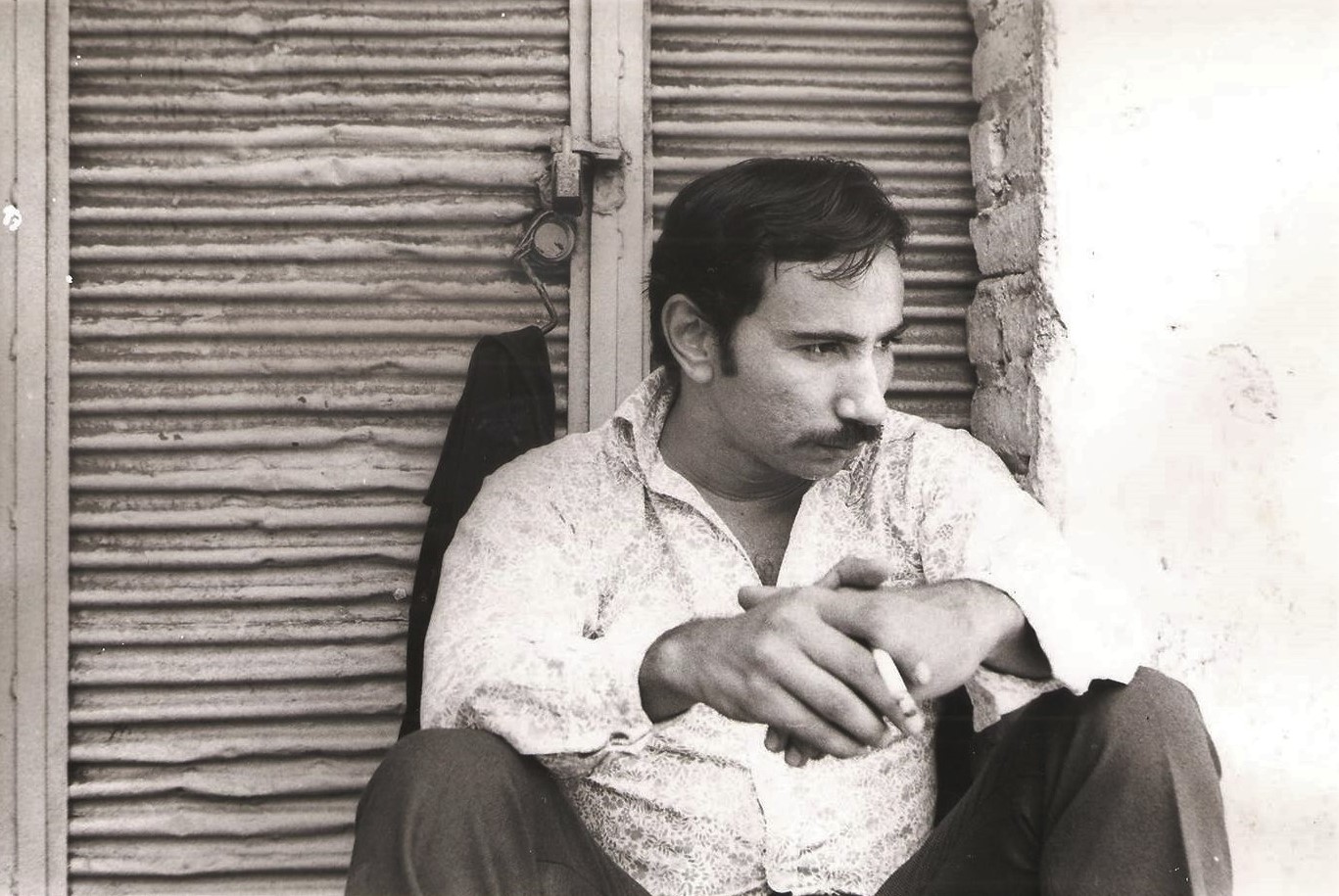

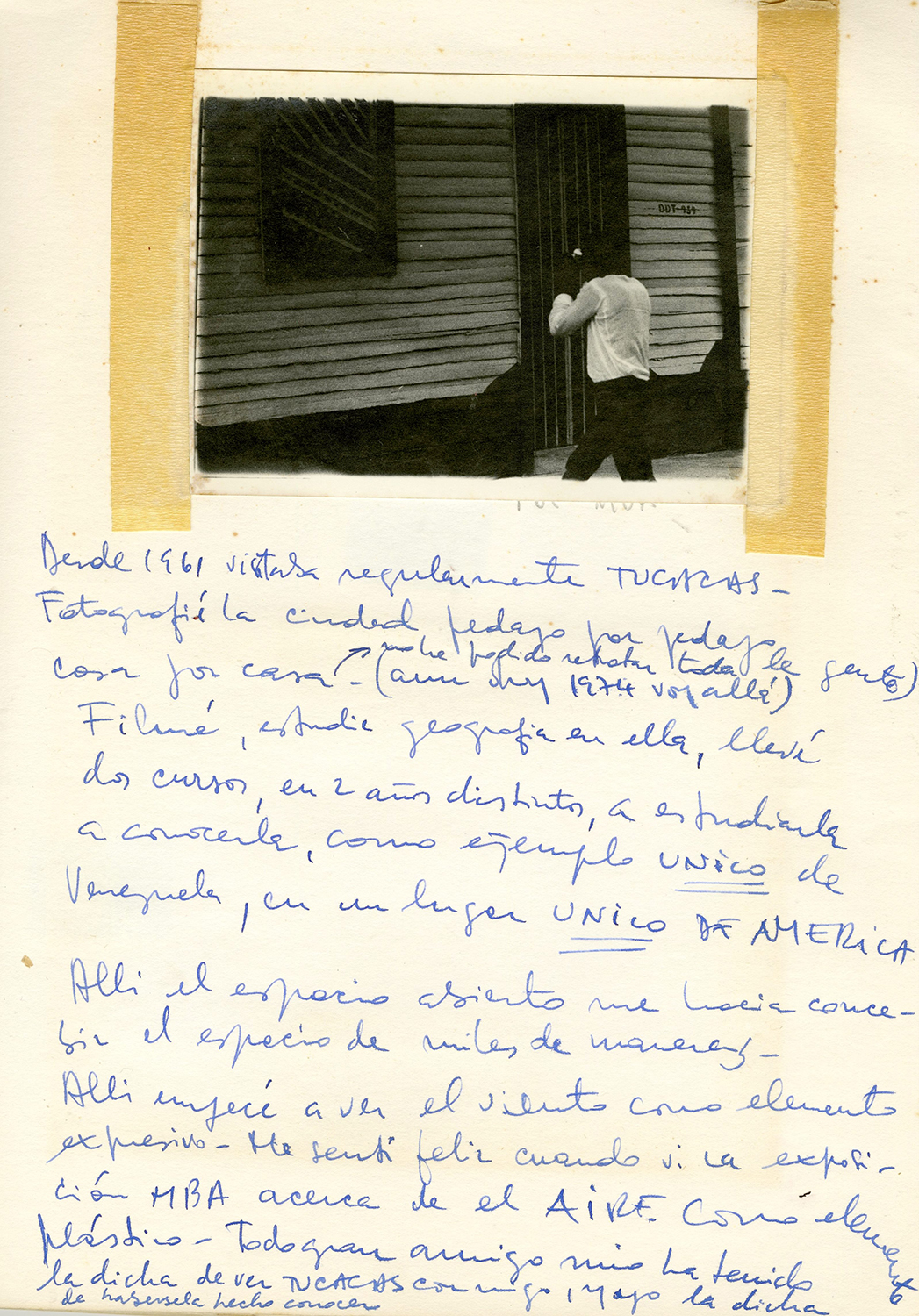

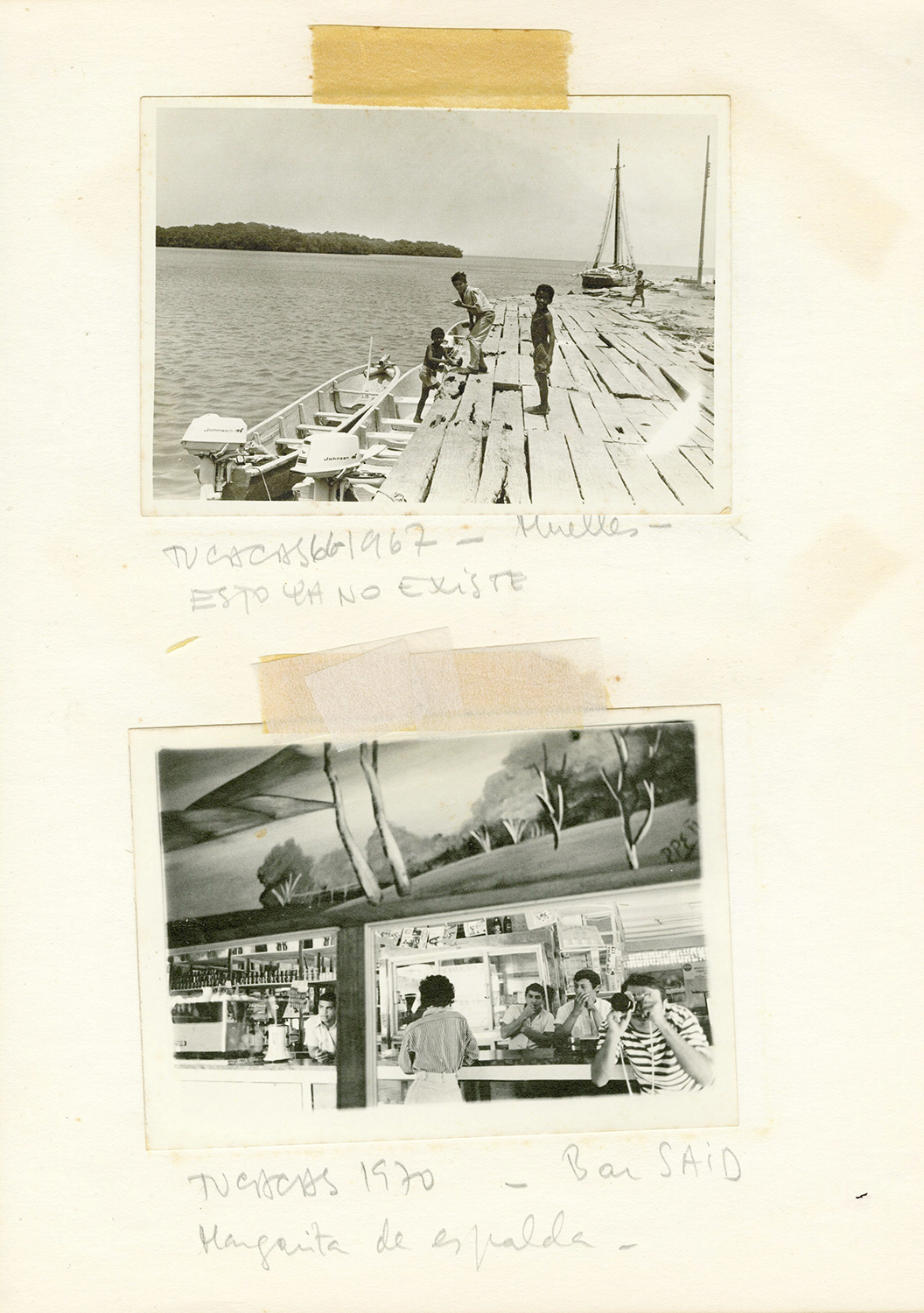

Perna's interest in documentation was not limited to this institutional project but went through his entire practice as a geographer, educator, artist, and person. He had gotten his first camera as a child, still living in Italy, which he used to make portraits of family and friends. After arriving in Venezuela and being deeply impressed by the landscape, he continued to record different locations during family trips and, over time, he deepened his practice, reaching the most experimental stage of his intervened photography. The artist offers this account using his signature image-text pairing in Historia de la fotografía de Claudio Perna narrada por Claudio Perna (1974), three autobiographical sketchbooks belonging to the Block Caribe series. Already in the first volume, he announces, “I like everything about Venezuela: its people and its things, its objects, its customs, its churches, its landscapes, etc. I have portrayed it all—I have documented it.”11 He also describes his trips to Tucacas—a coastal area in the state of Falcón—since the sixties, where he claims to have studied geography and taken “thousands of photos,” accompanied by his students and friends. To this place, precisely, belongs the image of a dock under which is written: "This no longer exists"—a powerful call to the need for registration in the face of a changing reality, a bet on the image as a source of knowledge and a basis for the writing of history.

Whether as a geographer or educator, as an artist or researcher, the fact is that Perna never stopped documenting. Because of his connective nature, he also never ceased to teach, unfolding this calling throughout his different fields of activity. Perna's constant exercise of writing—an endless discursivity that weaves works, diaries, and projects—constitutes in itself a pedagogical act, both (in)formative and educational, and open to the gaze of any reader. The fact that Perna titled this manuscript "ABC" reveals his position on the literacy potential ("in favor of collective clarification") of the project itself as well as of photography on its documentary side. The fact that today we can consider his writings as a classroom (about the country) also stems from his conviction about the role of public policies in the formative process of a society. It is clear that Perna's teaching practice was not limited to the UCV or Radar but permeated his travels around Venezuela and continued to overflow both as thoughtful writing and as a constant recording of images: metaphor and realization of an idea of wholeness.

A Geographic Perspective

In El ABC..., Perna proposes—among other things—a study of the relationships between human beings and a specific territory to establish an image corpus for a "Geography of Venezuela." Perna admits that "the geographical science (...) in the teaching aspect, allowed me many privileges: an orderly, systematic method applied to the facts of life, nature, human groups, and the most outstanding cultural facts—housing, roads, etc." His goal, then, must have been to "work geographically in life" and to resume the bond with "the landscapes we inhabit," which he considered as "permanent treasures."13 It is not by chance that he resorted to the geographer's method, which consisted in "placing things in relation to the totality of the planet. To observe, describe and, ultimately, interrelate the constituent elements of natural and cultural order."14 From this premise, his considerations regarding the connections between image and place, the human and geographic scale, local and global reality, are simultaneous and encompassing. Even in his defense of the Venezuelan identity and the rooting in this land ("the human scale is only attained by walking on foot"), Perna understands them as part of the "planetary earth" and considers the national and the international spheres as indissoluble realities. Thus, working geographically in life would not exclude in the human being an awareness of its own condition as a geonaut.

To illustrate this connective approach, Perna outlined the profile of what he considered a new professional kind: the photogeographer, "a geographer who, in addition to locating, observing, describing, and analytically interrelating, also records the evidence of his reflections through photography."15 The act of 'interrelating' became the basis of this system of knowledge production, as it could offer not only data and images of specific realities but also establish connections between them, complexifying and triggering the understanding of different realms of life. Hence, the utopian atlas proposed in El ABC... would no longer be based solely on a collection of maps nor on a compendium of portraits of human activity, but on a clearly constellar and hyperconnected model. The photogeographer, in Perna's words, was the "ultimate reporter: the reporter of Nature," someone working with life and with the ability to infiltrate one field into another in order to discover. The Pernian infiltration would be a gesture toward the combination of realities and images; a celebration of the possibilities of confluence.

The fact that anonymous photography was one of the triggers of this project is partly due to Perna’s understanding of it as a democratic genre in itself, as it was within everyone's reach thanks to the popularization of photographic resources. Thus, the visual compendium of Venezuela would be supplied by the people themselves, and so, the country would be able to educate itself through its own practice of self-documentation. From the gaze toward the other to the gaze at the self, the geographical component of El ABC... claims the importance of assuming oneself within and as a context; in a way, this ratifies Perna's concern about the equation Art = Life = Science.

If knowledge comes from the relationships between data and levels of experience, the context emerges as a foremost aspect in all educational processes: the surroundings in which people and places exist, contain and are contained. Perna makes a final appeal to this unifying will by quoting László Moholy-Nagy, who pointed out that specialized education only made sense if it produced an integrative human being, well balanced between the biological, intellectual, and emotional functions. Furthermore, alluding to the author, he added that "merely quantitative acquisitions do not contribute to the intensification of life nor the expansion of its purpose," which was no other than "handling life as a whole" and "situating oneself appropriately within the context of one's community."17 With this, Perna steps into the tradition of pedagogical reforms proposed by the social utopias and avant-gardes of the early twentieth century, in an attempt to reconfigure the concepts of 'artistic practice' and 'collectivity.'

The will to acknowledge the place of things in regard to the whole makes Claudio Perna's El ABC... a totalizing manifesto in favor of the construction of knowledge in relation with the environment. Its image-word structure reflects thinking processes while promoting the pedagogical possibilities of photography rooted in a specific reality. This gesture gains even greater sense as it emerged from the creation of the largest photographic archive in the country, attached to the main knowledge-gathering institution: the Biblioteca Nacional.

If Perna configured his multidisciplinary production as a vast archive, it would be logical to think—as evidenced in El ABC...—that he also conceived of the possibility of developing the country's education and knowledge from an archival practice: numerous, diverse, and specific, aware of the ephemeral, as visible as latent; where every image is a new archive, a potential unfolding of faces, places, history.