The Educational Work of Jorge Romero Brest

05/12/2023

A career dedicated to the permanent questioning of reality through art as well as to the formation of educators, artists and a critical public, skilled in the understanding and enjoyment of a particular mode of communication, the language of the visual arts [...]

Art Criticism As a Tribune

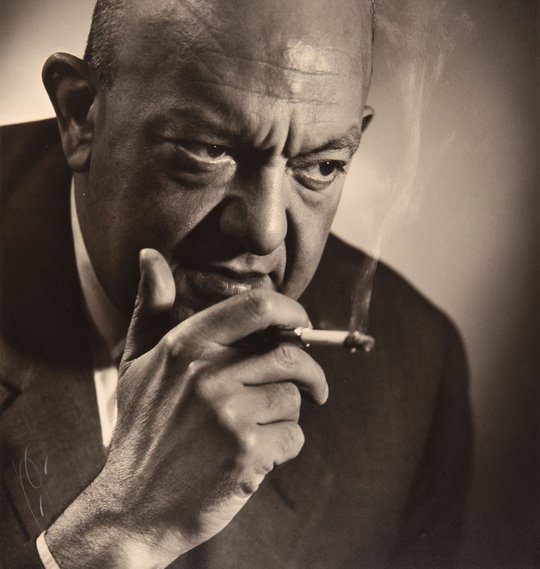

Art historian and critic Jorge Romero Brest (Argentina, 1905–1989) was a key figure for the dissemination of modern art in the Latin American context; an enthusiast of creativity committed to its context of production and autonomous in its means of expression. His pedagogical work began to stand out in the national field at the end of the 1930s, when he took his first steps as art critic in La Vanguardia, and later in the weekly political-cultural magazine Argentina Libre, platforms from which he taught criteria of value that would allow readers to discriminate the artistic from the general practice and to welcome the new modern practices without misgivings. In those years he began teaching courses and lectures in national and Latin American institutions—a way of connecting with people that would become one of his favorites—and in 1939 he was appointed professor in several chairs of the Colegio Nacional de la Universidad de La Plata.1

He was dismissed from his posts during the Peronist government in 1947, but this did not prevent him from persisting in his work as a teacher and trainer in modern art, a period in which, through his courses in Aesthetics and Art History taught in various places—including the Fray Mocho bookstore—and at the Universidad de la República in Montevideo, he managed to attract around him a group of advanced students (graduates of careers such as literature or architecture) who would later become influential art professionals in the national, regional and international scene. Marta Traba, Damián Bayón, Clara Diament, Blanca Stábile, and Samuel Oliver stood out particularly in the Latin American scene as critics, curators, gallery owners, or cultural managers.

With the collaboration of these disciples, in 1948 he founded the magazine Ver y Estimar, a publication dedicated to the visual arts that reviewed exhibitions in the country and abroad, dedicated special issues to the study of artists and presented new methodologies for approaching art with the purpose of educating the public in the enjoyment of it and, at the same time, training a new generation of critics. Through this magazine, he encouraged the dissemination and analysis of artistic activities from an open formalist perspective in which the implicit sociological aspects were not disregarded. It was an editorial project conceived at a very particular moment of the national scene: there were still intense debates about the profile of Argentine art that negatively assessed the situation in which it found itself.

The magazine actively intervened in them, discouraging young artists from following the path of regionalist folklorism of Spanish heritage and insisting on the importance of renewing expressive tools and creative independence.

So much so that by the end of 1940, Ver y Estimar decided to unquestionably support abstract art, defining a specific esthetic program that guided the criteria for attributing value to it or dismissing it, with a universal esthetic and social ideal on the horizon. The publication had a network of Latin American and European collaborators, formed thanks to Romero Brest's travels, which allowed for periodic reports on the course of artistic activities outside the country and the consequent approach to art from an international perspective. This constantly renewed the field of problems and will always be a key issue in the critic's reflective gaze.2

In 1955, with the Revolución Libertadora and the overthrow of Perón's presidency, Romero Brest assumed the direction of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (MNBA). During his tenure, he worked to transform the museum from a mere repository of works of art into a "living art center" by carrying out a profound process of modernization of its areas and activities. One of the main strategies to turn the museum into an institution frequently visited by the public was to increase the number of temporary exhibitions that constituted a diverse calendar throughout the year.

The art of the younger generations had a privileged place; in addition, the national awards granted by the Di Tella Foundation (before it had its own headquarters) were exhibited in the halls of the museum.

During his administration, the conservation department, the cabinet of prints, an education department and an auditorium with the latest technology were also created to offer courses and lectures related to current exhibitions or to topics considered key to education in modern art, as in the case of the course dedicated to the work of Picasso. The rooms dedicated to exhibiting the museum's permanent collection were organized for the first time according to a curatorial script that articulated the assembly of Argentine works with that of European works, establishing a clear Western affiliation for local art and the necessary artistic legitimization. In 1963, Romero Brest left the direction of the museum as a consequence of the scarcity both of resources and staff suffered by the institution along with the conflicts that arose with the General Directorate of Culture due to differences of criteria in the acquisition and exhibition of artworks.3

The Commitment to New Art and the Approach to Latin American Art

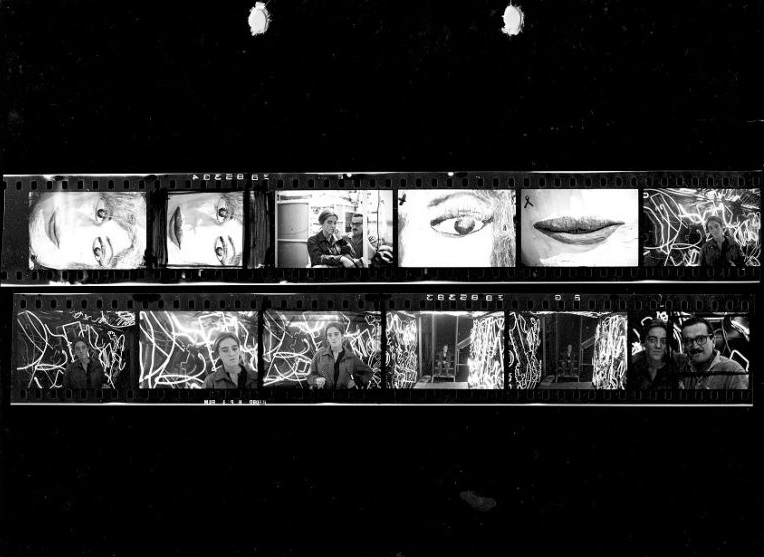

After resigning from the MNBA, he took over the direction of the Centro de Artes Visuales (CAV) of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella—to which he had been an advisor since 1960—where he supported and encouraged the most experimental artistic practices of the period in the country. From the already mythical institution and during the seven years of Di Tella's adventure, he encouraged the creative work of a great generation of young artists and made his modernist criteria more flexible by welcoming experiences such as objects, settings, shows and happenings in the institution's halls.4 The annual national prizes awarded by the institution provided travel grants to artists, while the International Prize aimed at the insertion of Argentine art abroad, with the summoning of a team of foreign jurors and the participation of North American and European artists who were in competition with Argentine ones.5

The extraordinary promotion of the participatory events through the mass media made possible the socialization of contemporary art and the construction of a wider public, although misunderstandings and criticisms also undermined the project: the internationalization of artistic practice seemed at that time alien to the Latin American context of production.

The closure of the Di Tella—due to a shortage of funds, the growing opposition of the de facto government and the impossibility of a transformation for the institution required by Romero Brest—gave way to the last, very brief, institutional responsibility assumed by the critic in July 1970. With the creation of an industrial design company ‘Fuera de Caja, Centro de arte para consumir,’ he sought to contribute to improving the aesthetic quality of the everyday through the design of objects for domestic use. This project had originally been conceived for the Di Tella Institute: together with a television studio, Romero Brest had proposed transforming part of the CAV's central exhibition space into a place to sell objects designed by artists. The gallery was intended to carry out his new conceptions: supporting a project that pursued total aestheticization as the only alternative, in search of the broadening and renewal of society's aesthetic sensibility.

Soon after, the difficulties and inadequacies between mass consumption and artistic production showed that it was an unviable enterprise at the time. Once away from institutional management, Romero Brest resumed his writing work and returned to art criticism for cultural magazines such as Crisis and cultural supplements of national newspapers. During this period, he withdrew into a reflective and self-critical work, both personally and professionally. On the one hand, he reviewed his recent past in search of answers to the misunderstanding of the medium, and on the other, he broadened his gaze towards the arts of Latin America. While his participation in the Argentine media was scarce, the decade inaugurated for him a series of collaborations in prestigious magazines abroad, such as the Mexican Plural and Artes Visuales, the Colombian Eco Revista de la cultura de Occidente, the hemispheric Visión, and the Portuguese Colóquio/Artes.

Keeping the African continent on his horizon of social utopia, his book Política artístico visual en Latinoamérica [Visual Art Politics in Latin America] proposed to promote the region's art by changing the political strategy and working primarily on a recognition and stimulation of the esthetic conscience that was the true foundation of Latin American societies, so that art could fully express its link with the surrounding context. Only in this way could contemporary creative production in Latin American countries be socially assumed as their own. Art had to respond to the collective interests of Latin America and be representative of the regional culture. Faced with a cultural reality degraded by the mass media, a fresh start had to be made: art had to contribute to the aestheticization of everyday life.

During this period he intervened as a specialised critic in several Latin American biennials—for example, the Coltejer Biennial in Medellin, in 1972, or the Bienal Latinoamericana in Sao Paulo, in 1978—and was invited to participate in several debates on the state of Latin American art and its identity that took place during the decade, as the one developed through the pages of the Mexican magazine Artes Visuales. However, his writings based on a rigid idealistic perspective left him more and more on the sidelines of the prominence he had been able to occupy years before.6

To the Rescue of Art

During the last stage of his life, Romero Brest believed it was crucial to reconsider the artworks that were still authentic, to "rescue art" by recovering canonical works of Western art, and to try to clarify what it was that had made them works of humanity. In tune with this need, in the 1980s, he returned informally to institutional activity. Marta Nanni, then in charge of the permanent collection of Argentine art at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, invited Romero Brest to collaborate with her in the exhibition design of the new installation.7 Both agreed on a reading of Argentine art that emphasized a strictly aesthetic approach to both the artworks and the art history. With the new curatorship, the museum thus established a canon of capital works of national art.

Romero Brest was closing a career dedicated to the permanent questioning of reality through art as well as to the formation of educators, artists and a critical public, skilled in the understanding and enjoyment of a particular mode of communication, the language of the visual arts. For all these reasons, his figure occupies an undisputed place in the historiography of modern Latin American art.