Art and Education in the Americas

02/23/2022

by Félix Suazo

In the midst of the institutional transformations in the field of art education that have taken place in the continent, there have been some exceptional initiatives carried out by artists who propose a link between art and pedagogy beyond conventional spaces and programs, from their own practices as creators (...)

New Teaching Methods: Reforms and Experiments

At the beginning of the twentieth century, almost all nations in the Americas showed signs of artistic and cultural renewal. With a double twist—the national on the one hand, the universal on the other—the continental avant-garde sought to emerge from the academic tradition, assume local singularities, and incorporate the changes of modern life. However, the challenge was great, considering the outdated educational apparatus of the time, along with the no less decisive socio-political contradictions of the time.

Some of these difficulties were resolved with the public reforms aimed at overcoming illiteracy and inequality, among which the program undertaken by José Vasconcelos in Mexico at the head of the Secretariat of Public Instruction, between 1921 and 1924, stands out. Following the premise of an education linked to experience developed by authors such as John Dewey in the United States, Adolphe Ferriére and Jean Piaget in Switzerland, and Maria Montessori in Italy1, Vasconcelos focused on popular instruction, creating rural schools (cultural missions), high schools and technical schools, producing mass publications of classical authors, and supporting mural art. He also established partnerships with foreign institutions for vocational training and invited renowned intellectuals from across the continent to collaborate with the educational renewal, including Chilean educator and poet Gabriela Mistral, as well as Dominican philosopher and writer Pedro Henríquez Ureña.

Another part of the educational efforts shouldered on the continent was resolved with study trips to Europe or, to a greater extent, with the mastership of European migrants who arrived in the Americas. Particularly significant was the arrival to continental lands of former directors, professors and disciples of the Bauhaus (1919-1933), after it was shut down by the Nazi government. Spouses Annie and Josef Albers, who joined the Black Mountain College in North Carolina, as well as Walter Gropius and Marcel Lajos Breuer, who taught at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, were established in the United States. In Mexico, Hannes Meyer became a professor at the School of Architecture and Engineering of the National Polytechnic Institute and worked at the Department of Housing in the Secretariat of Labor. In Argentina, Grete Stern photographed the indigenous population and also taught. In Chile, Tibor Weiner and Max Bill embraced architectural and urban projects in Santiago and Valparaiso. Their ideas and those of their disciples were based on the premise that "form follows function." They searched for usefulness and practicality in art, architecture, urbanism, and design; these aspects helped in the process of cultural modernization throughout the continent.

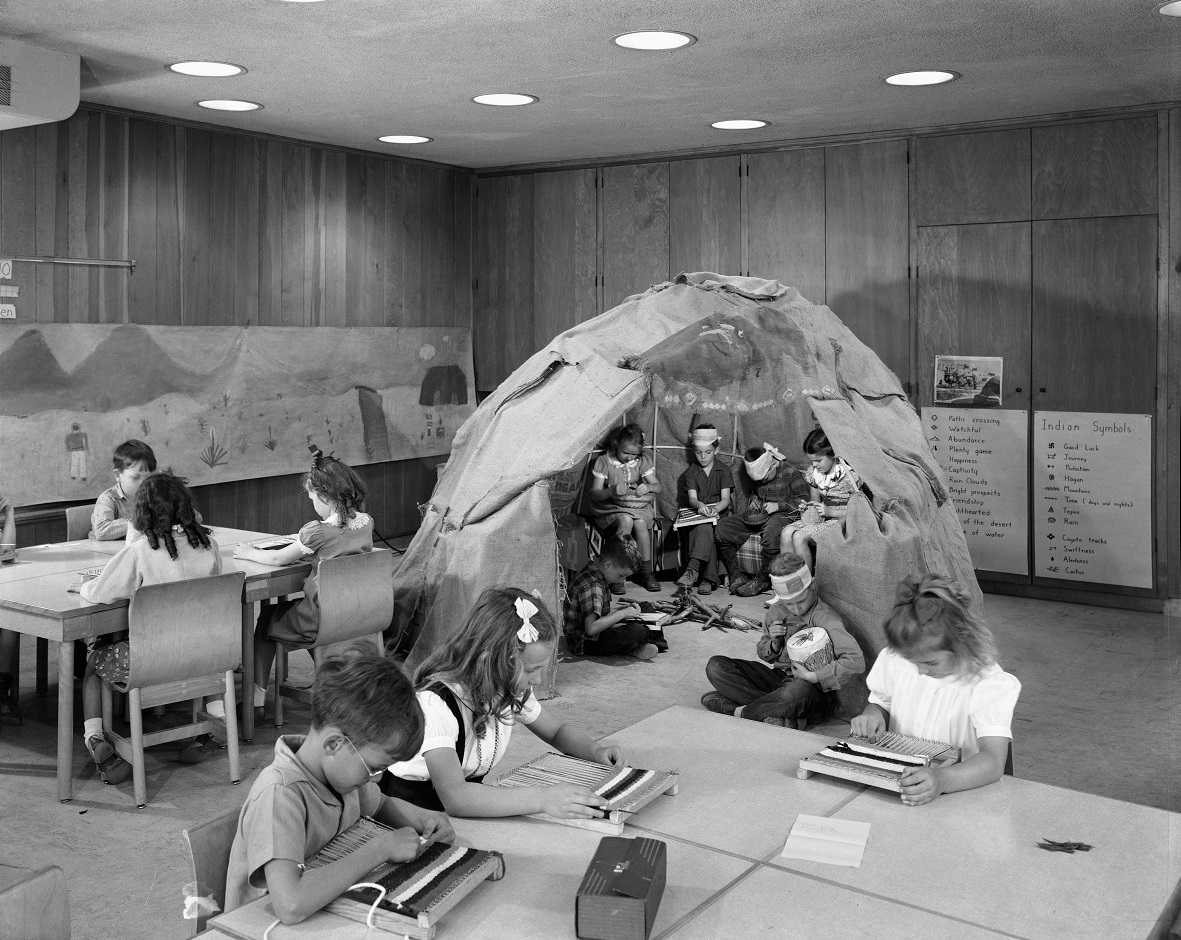

Generally speaking, the training models that were implemented during the first half of the twentieth century were based on the integrality, experience, and social sense of education. The need to connect art teaching with the demands of the surroundings stimulated the emergence of experimental workshops, schools and universities. Subsequently, some of these training centers became epicenters of the artistic renewal currents of the continent.

Black Mountain College (BMC) (1933-1957), in North Carolina, trained some of the main figures of abstract expressionism, Op Art, music, dance, performance, and American literature of the time. Created as an experimental university, the BMC offered an interdisciplinary education that brought together well-known artists, designers, and poets. In this environment, Dewey's proposed thesis of ‘art as experience’ found auspicious ground, where work, volunteering and collaboration were an essential part of artistic education. These ideas show in several of Josef Albers' pedagogical writings, arguing that "real art is essential life and essential life is art,"2 so the main purpose of artistic training is "to teach the student to see in the widest sense: to open his eyes to the phenomena about him, and most important of all, to open to his own living, being, and doing."3 He stated that, more important than imitating and memorizing data is "having seen and experienced."4 From his perspective: "It is better to be able to really draw a signboard than to be content with unfinished portraits."5 In short: "At Black Mountain College, art is considered as educational as language, mathematics, philosophy. It is accepted here also that practical, manual work is as essential in education as it is in life."6

In Montevideo, Uruguay, the School of the South (Escuela del Sur) (1943-1975) taught the basics of constructive language based on the teachings of Joaquín Torres-García (1874-1949), a master who supported his program on the universal values of geometry and symbolism. In this sense, the School of the South emerged as "a reaction against the environment which it intends to overcome, not only to position itself in unison with the youngest schools of our time, but also trying to find an art of our own that can respond to the future art of the Americas."7

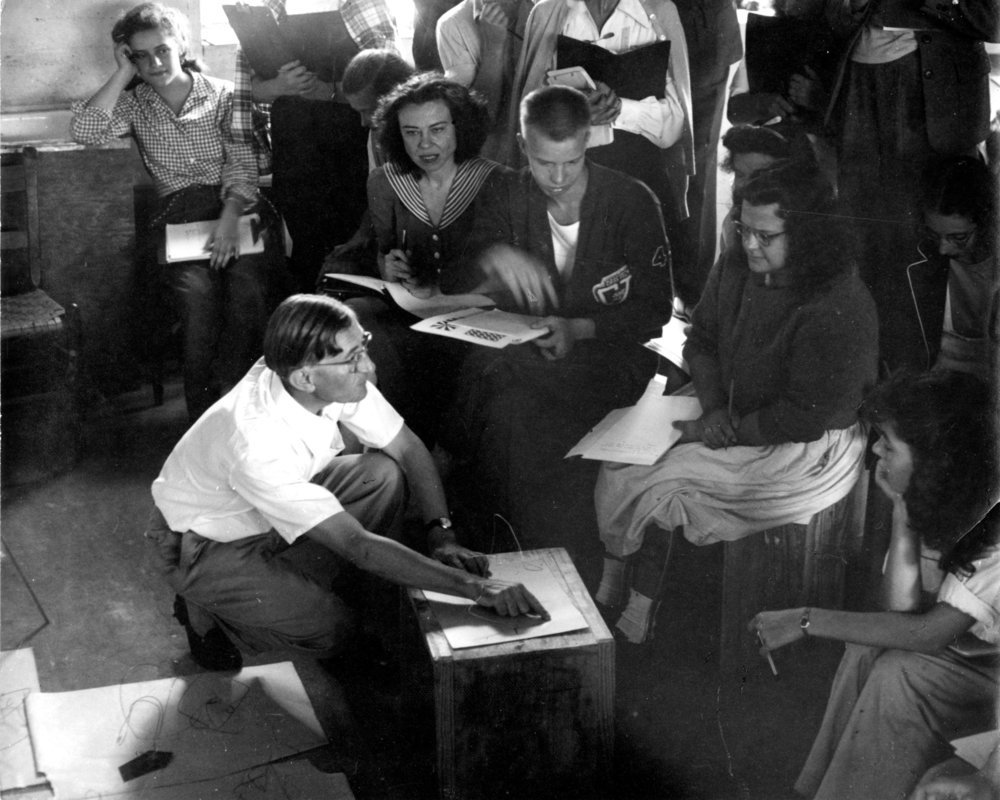

With a Latin Americanist approach, Torres-García invoked the fusion of Indo-American geometry and universal symbols. He gave weekly talks on art, accompanied by demonstrative diagrams of his theories. His method of ‘learning by doing’ included geometric simplification, orthogonal sorting, and the use of the golden section as distinctive elements of the Taller Torres-García. Without a preset program, the students of the workshop developed their drawing and painting works at their own pace, each of them under the direct orientations of the maestro and support from the more advanced pupils (some of whom would later become teachers at the Taller, such as Julio Alpuy and Gonzalo Fonseca). In addition to the personalized treatment of each student, collective tasks were proposed such as murals, exhibitions and publications, in which all the disciples participated. Torres-García's pedagogy allowed "(...) his students to learn the history of the arts through practice, and not just from theory."10

Contexts, Models and Institutions

By the second half of the twentieth century, new training spaces were created, several of which had a significant impact on the methods of artistic teaching on the continent.

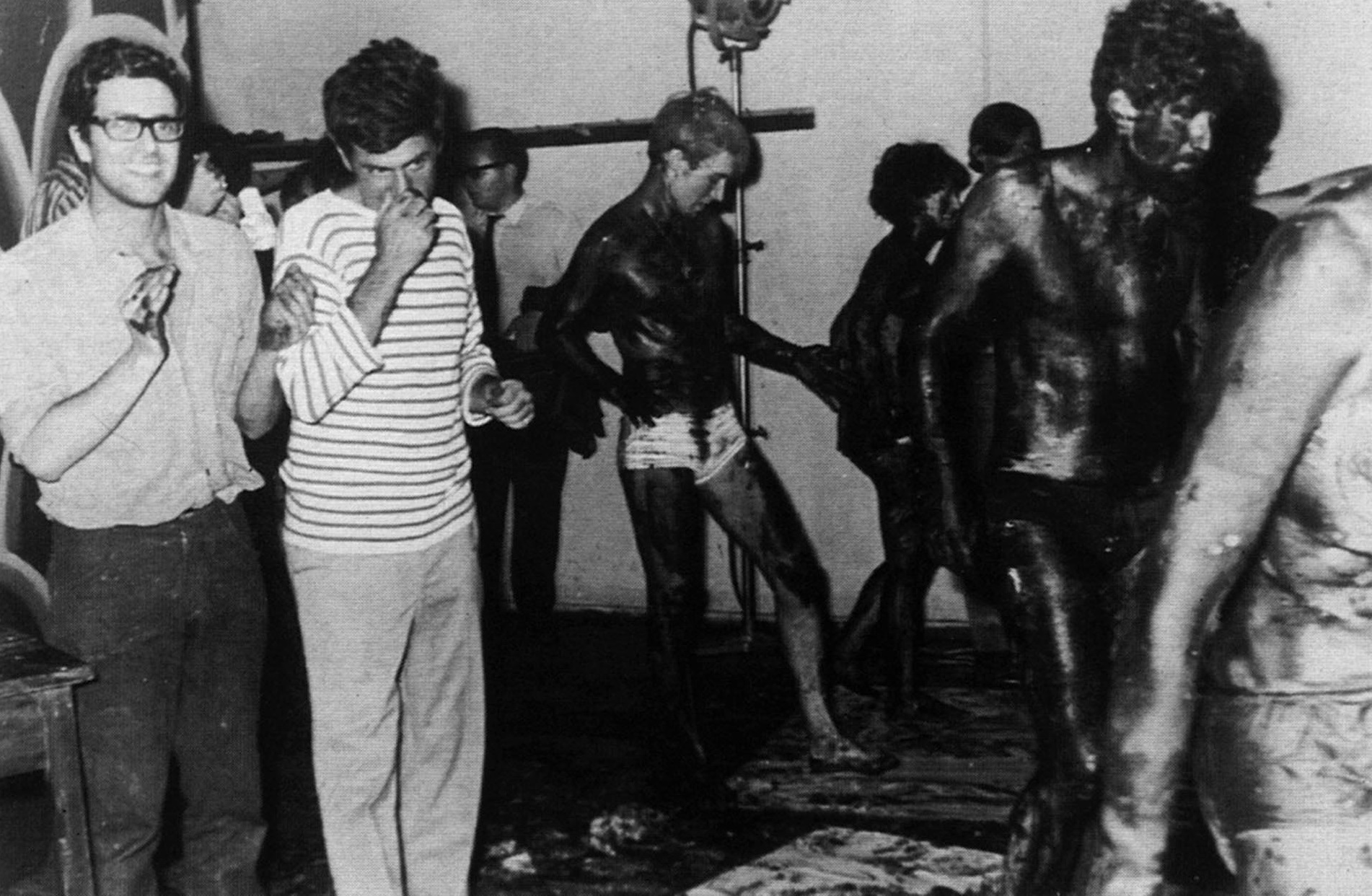

The Argentinian theatrical, musical and pictorial avant-garde gathered at the Torcuato Di Tella Institute (ITDT) (1958-1970) in Buenos Aires, opening the way for the development of happenings, performances, installative and multimedia experiences. From the Visual Arts Center (CAV), under the direction of critic and historian Jorge Romero Brest, the ITDT foregrounded the work of artists such as Antonio Berni, Jorge de la Vega, Juan Carlos Distéfano, León Ferrari, Edgardo Giménez, Gyula Kosice, Julio Le Parc, Marta Minujín, Dalila Puzzovio, Luis Wells, Rubén Santantonín, Marilú Marini, Nacha Guevara, Gerardo Gandini and Les Luthiers, among others.

In the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, the philosopher and educator Paulo Freire (1921-1987) led the Department of Cultural Extension at the University of Recife from 1961 to 1964, where he applied his educational theories with illiterate workers. This is where the principles of his "critical pedagogy" were conceived, whose foundations he published in books such as La educación como práctica de la libertad (Education, the Practice of Freedom) (1967) and Pedagogía del oprimido (Pedagogy of the Oppressed) (1968). Freire questioned the "banking concept of education" that, from his point of view, conceived the students as "recipients" of alienating offers, in the face of which he advocated a liberating approach, based on the cultural, ideological, political and social context of the pupils. He asserted: "... the educator has to be sensitive; he has to be an aesthete. He must have a taste. Education is a work of art (...) the educator is also an artist, he re-does the world, he re-draws the world, re-paints the world, re-enchants the world, re-dances the world (...)."11

In Caracas, the Neumann Foundation’s Design Institute (IDD) (1964-1995) was created to respond to the graphic requirements of the Venezuelan industry, with professorships of the country's most outstanding engravers, illustrators, designers, typographers, and writers, including Gerd Leufert, Gego, Santiago Pol, and Carlos Rodríguez. By the early 1970s, the legendary Cristóbal Rojas School of Visual Arts was already insufficient for the creative and conceptual demands of the time, which also happened in alarming proportions in other institutions for artistic training in the country. In addition to the aforementioned Neumann Foundation’s Design Institute, this requirement was fulfilled by the School of Arts (1978) of the Faculty of Humanities and Education of the Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV), the Art Department (1972) of the Pedagogical Institute of Caracas (IPC), and the overseas scholarship program of the Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho Foundation (1975). The creation of the Instituto Universitario de Estudios Superiores de Artes Plásticas Armando Reverón (IUESAPAR) in 1990 (transformed into UNEARTE in 2008), brought about an educational program in visual arts that aimed to train integral artists. There taught some of the artists leading the renewal of drawing, painting, installation, and performance, such as Víctor Hugo Irazábal, Antonieta Sosa, Nan González, Carlos Zerpa, Consuelo Méndez, among others. Researchers and curators such as Sandra Pinardi, Luis Pérez Oramas, Ariel Jiménez and María Luz Cárdenas also held professorships in this institution. The first graduates of this experiment would quickly enter the exhibition circuit, equipped with multi medium training, both technically and conceptually.

In Valparaiso, Chile, Open City (Ciudad Abierta) was created in Ritoque as a "humanistic invention"12 devoted to experimental education, located on a 300 hectares plot acquired by a cooperative of students and teachers of the Faculty of Architecture of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso in 1971. In this environment, the architect, researcher, painter and teacher Manuel Casanueva (1943-2014) developed the ‘Curso Cultura del Cuerpo’ (CCC) (‘Body Culture Course’), from which the Tournaments (1972-1992) came out. These were open conclaves of a playful and performative nature, focused on design and architecture exercises, considering the cultural, environmental and bodily aspects. In these experiences, students worked with unconventional elements such as balls, stilts, nets, ropes, gloves, ribbons, spheres, polyhedric structures, flags, hats, helmets, kites, and mantles, among others. However, Casanueva warned: "That it is experimental architecture does not mean that something may fall or collapse for not having previous calculation, it is not a simple ‘accident.’ From this standpoint, this line is as professional as the most professional."14

The Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA) (1974) opened its doors in Havana, Cuba, initially with faculties of Music, Visual Arts, and Performing Arts. There taught several prominent figures of the so-called ‘Cuban Renaissance’ of the eighties, such as José Bedia, Flavio Garciandía, María Magdalena Campos and Lázaro Saavedra. Several generations of artists were trained in this environment; some of them stand out by the international reach of their work, such as Belkis Ayón, René Francisco Rodríguez, and Los Carpinteros, among others.

In the late 1970s, several students from the National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving “La Esmeralda,”15 in Mexico City, conformed the Grupo Germinal "as a self-education alternative to official pedagogical methods and contents."16 The group members—Joaquín Conde, Yolanda Hernández, Carlos Oceguera, Silvia Ponce, and Mauricio Gómez Morín—proposed a link between art, community pedagogy, and critical activism. From this premise, they conceived of the method of Developing creativity through the visual arts, "which was about seeking everyday experiences of life and the community to express them visually,"17 and whose origin goes back to the art education workshops for children implemented by the group in the town of Escuinapa, Sinaloa, during the summers of 1977 and 1978. The group also oriented their activities towards the production of banners for popular demonstrations and conducting workshops on monumental graphics for civic and political organizations, as they were resources for the "collective visual communication" beyond traditional art spaces.

In Lima, Peru, the Corriente Alterna School of Visual Arts and Design (1992) offers rigorous humanistic and professional training of interdisciplinary nature, attuned to the demands of the cultural circuit, seeking to "articulate the questions that the pedagogical field of the school produces in regard to the local and international art world."18 Founded by engineer, entrepreneur, collector and philanthropist George Grünberg (Zurich, Switzerland, 1938) and businessman, collector and cultural manager Carlos Llosa, the institution was run by artist, educator and activist Claudia Coca between 2011 and 2018. Their graduates are not only artists and designers, there are also gallerists, curators, and cultural managers.

In Guayaquil, Ecuador, the Instituto Superior Tecnológico de Artes del Ecuador (ITAE) (2004-2017), helped in structuring the contemporary local art scene and shaped a different image of the artist in the new millennium19. It encouraged the development of a critical behavior toward the context and promoted the participation of students in the exhibition circuit—purposes that yielded fruitful results. With initial support from the artist Xavier Patiño, a member of the group La Artefactoría (1982-1990), the ITAE housed the teachings of Marco Alvarado (another member of La Artefactoría), Cuban artist Saidel Brito, professor and curator Lupe Álvarez, curator Ana Rosa Valdez, among others.

Beyond their logistical, methodological, and conceptual specificities, each of these spaces played a significant role in the training and advancement of several generations of artists in the Americas. Owning to this mastership are the wide variety of creative practices that crystallized into different currents and languages of artistic renewal, based on an open pedagogy, not only aimed at educating artists but also to broadening the cultural horizons of large human collectives. This comprises certain variants of performance and community activism of the seventies and their recent extensions, such as site-specificity and environmental struggles, visual didactics and museum management for different-abled audiences, participatory art and the debate around the inclusion of vulnerable groups, among other models crossing life and art that answer to the pedagogical calling of art and artists. Along this direction, we catch sight of various genealogies ranging from constructive language to neo-concretism, from color interaction to polysensoriality, from gestural to behavioral art, from public muralism to political contextualism, from representation to immateriality, from introspective inquiries to narratives of displacement, and from authorial positions to shared authorships, just to name a few of the most vigorous and fruitful variants of art in the Americas.

Teaching Artists (A Synoptic Approach)

In the midst of the institutional transformations in the field of art education that have taken place in the continent, there have been some exceptional initiatives carried out by artists who propose a link between art and pedagogy beyond conventional spaces and programs, from their own practices as creators. Some of them have already been mentioned along this journey (Josef Albers, Joaquín Torres-García, Manuel Casanueva Carrasco, etc.).

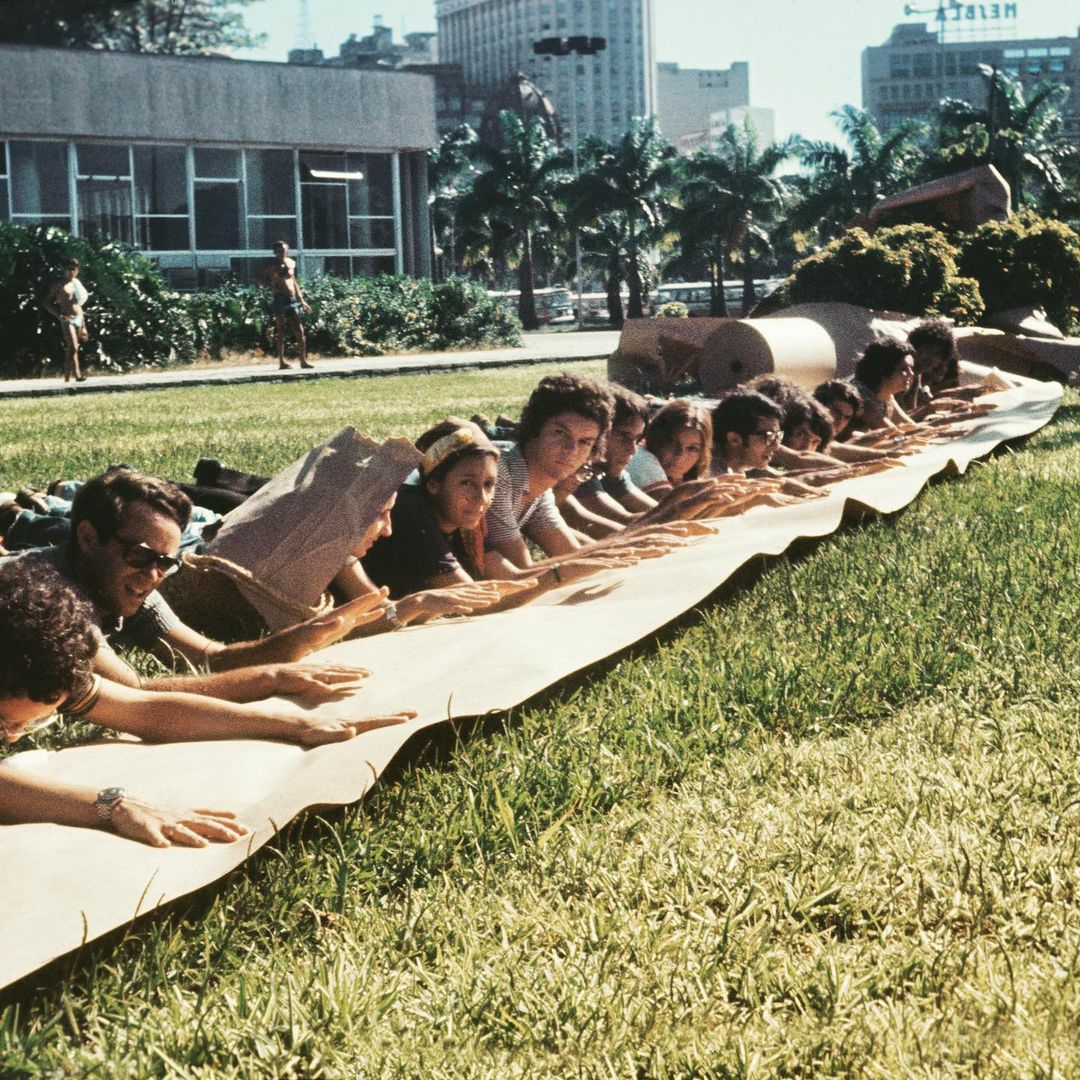

They are joined by teaching artists such as the Venezuelans Asdrúbal Colmenárez (1936) with his experiences at the Centre Universitaire Expérimental de Vincennes, in Paris, and the Alphabet polysensoriel (Polysensorial Alphabet) (1980), and Claudio Perna (1938-1997) at the School of Geography of the Universidad Central de Venezuela and RADAR, where he embraced the educational notions of Simón Rodríguez (1769-1854). Equally relevant are the propositions of Brazilian Lygia Clark (1920-1988) with her ‘Espacio del Cuerpo’ (1970-1975) at the Sorbonne University in Paris; Uruguayan Luis Camnitzer (1937), with his thesis on ‘art as education’ and the site-specific installation A Museum Is a School (2009-2015); Colombian Antonio Caro (1950-2021) with his community workshops; Mexican Pablo Helguera (1971) with his ‘transpedagogy’ (2006), and the Cubans Tania Bruguera (1968) from the Cátedra Arte Conducta (Behavior Art School) (conception: 1998 / execution: 2002-2009) and René Francisco Rodríguez (1960) with the project Desde una Pragmática Pedagógica (From a Pedagogical Pragmatic). There are also a number of young teaching artists among which are Venezuelan Miguel Braceli (1983) and Colombian Nicolás Paris (1977), who base their artistic-pedagogical work in space, materials and the body, drawing a connecting line to preceding experiences.20

I conclude this brief overview with the Brazilian artist, educator and researcher Mônica Hoff (1979), who works within the friction zone of art, pedagogy and curatorship, with an emphasis on a collaborative, liberating and critical vision. "I am far more interested in the idea of getting ourselves organized so we can build together what we want to learn and then everyone can develop their methodology."21 Hoff has been coordinator of the Teaching Networks of the 9th Mercosul Biennial (Porto Alegre, 2013) and the Biennial’s Educational Program (2006 and 2014), where she has implemented her ideas with the intention of thinking (...)

"...the relationship between art and other areas of knowledge in the field of education from the perspective of art not as a discipline but as a creative engine of the educational structure, especially the school in which the artist is not a bad teacher, but a 'proponent, an entrepreneur and an educator', as suggested by Hélio Oiticica in 1967."22

Teledidactics: Mistral, Traba, D’Amico

Another milestone in artistic pedagogy on the continent stems from the incorporation of audiovisual technology into the educational process. The didactic proposals of Chilean poet and educator Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957) and that of Argentinian critic and art historian Marta Traba (1930-1983), as well as the informative work of Venezuelan journalist and educator Margarita D'Amico (1938-2017).

With long experience in rural education, Mistral recognized the importance of the audiovisual, particularly television and film as educational media. In a text dated 1956 she wrote: "To the home of the Word, which we call School or College, has come a formidable competitor: the image."23 She was convinced of the benefits that the audiovisual would bring to the literacy process. She would say: "What visual teaching is already giving us for adults is admirable, and it is a whole feast for schoolchildren who enjoy every day with the capital teachers called Image, Color, Heard Story, and Enjoyed Vision."24 She vehemently affirmed that: "All grades of education (...), from unhappy elementary schools to universities in poor countries, can achieve the effectiveness and realization of their purposes as long as a wide endowment of these master assistants arrives at them: Radio, Film, and Television."25

Also passionate about the possibilities of television, Traba granted this medium an important educational role. "Personally—she said in an interview—I believe in TV as a vehicle of culture, and everything about it excites me."26 Between 1954 and 1958, she developed an intense informative-pedagogical activity on Colombian public television through the shows La rosa de los vientos (The Wind Rose) (1954), dedicated to her travels, and El Museo Imaginario (The Imaginary Museum) (1954), where she commented on European art plates, especially of the early avant-gardes of the twentieth century. She also had a show called Una visita a los museos (A Visit to the Museums), which was broadcasted on Friday nights in early 1955, devoted to European museums; while producing the show El ABC del arte moderno (The ABC of Modern Art), dedicated to the dissemination of Colombian art. In 1957, she presented Curso de historia del arte (Art History Course), running for 38 episodes, from prehistoric art to the twentieth-century avant-gardes, and immediately after, Ciclo de conferencias (Conference Cycle). In 1966, she made the program Puntos de vista (Points of View) on a private station and by 1983 she recorded the 20-chapter series Historia del arte moderno contada desde Bogotá (Modern Art History as Told From Bogota), recorded in public places, buildings and artist workshops. For Traba: "Television is a great conduit for reaching the people; they see the teacher, they are aided by the illustrations presented on the screen and, over time, they grow fond of the professor."28

A few years later, Mistral and Traba's premonitions on the role of audiovisual media would be the subject of reflection of Venezuelan journalist, art critic and teacher Margarita D'Amico, who published Lo audiovisual en expansión (Monte Avila Editores, Caracas, 1971), a pioneering book about the impact of television and film on world culture. Aware of the experimental currents in music, video art and performance, D'Amico reviewed and interviewed in her press columns the most outstanding personalities of the time, including Canadian professor and communications theorist Marshall McLuhan. She also organized at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Caracas, in 1975, the exhibition Arte de Video (Art of Video), a project that gathered artists such as Douglas Davis and Charlotte Moorman, attracting 56,000 visitors in 16 days. In her tireless doing, she also directed the television series Arte y Ciencia and Pioneros, as well as the radio show Vanguardia hipersónica.

From the website La Bohemia Hipermediática—an online project of the Center for Humanistic Research and Training at the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB) devoted to the dissemination of her legacy—D'Amico asked the question: "How do we deal with the avalanche of media and technologies available to artists and audiences today?"29 Aware of the technological changes and their effects on contemporary culture, she wrote: "In addition to the new and traditional, real and virtual media, the second decade of the 21st century reveals the supremacy of infoaesthetics, urban projectionism, installations, performances, spatial aesthetics, archaeology of the present, musical retromania, and interactive applications for iPad, iPhone, iPod, conceived by artists that are highly committed with current technologies (...). Researching the mediums, deciphering aesthetic codes on the spot, is quite complicated. Understanding 'new' trends in their real dimension is even more difficult, especially if backgrounds are unknown, such as the artistic avant-gardes of the 20th century or the musical languages of the pre-millennium and post-2000."30 Following this orientation, she made much of her articles, catalogues, photographs and video files available online for younger generations.

Mistral, Traba, and D'Amico understood that mass media—television, film, photography and, more recently, social media—are an important educational element in bringing art content more efficiently and to more people. In this sense, they anticipated the possibilities that opened with the emergence of digital platforms where tutorials, courses, documentary works and archives are already very frequent, many of them specializing in visual arts.