The Radical Pedagogy of Celeida Tostes

10/16/2023

Leia este artigo em português aqui.

The emancipatory, dialogic, and experimental character of Celeida Tostes' pedagogy and its intertwining with her artistic practice remains one of the most radical examples of art education in Brazil [...] She did not seek to inculcate aesthetic standards in the students, but to help each one find their own language in a process of self-reflection and experimentation.

When in 1950 Celeida Tostes (Rio de Janeiro, 1929 - Rio de Janeiro, 1995) began the serial course of Engraving at the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes - ENBA [National School of Fine Arts] of the University of Brazil, in Rio de Janeiro, then capital of the country, Brazil was living a moment of institutional expansion in the field of visual arts from the installation of museums: Museu de Arte de São Paulo (1947); Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (1948); Museu de Arte Moderna de Rio de Janeiro (1948), and the appearance of newspaper and magazine columns devoted to the arts.1 Also, in 1948, the Escolinha de Arte do Brasil2 [Little Art School of Brazil] was founded by Augusto Rodrigues, which focused on the artistic education of children and the training of art teachers. With the creation of the São Paulo Biennial (1951), the course of internationalization of the Brazilian artistic milieu accelerated. Thus, there was an expansion and qualification in the offer of education and information about art in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Education already stands out as a simultaneous interest of Celeida Tostes, who had recently graduated in arts. In 1956, she enrolled in the Course of Artistic Activities for Kindergarten Teachers and the Elementary School Course promoted by the Escolinha de Arte do Brasil. Her pedagogical improvement continues in the the Drawing Course, with training in Painting, Advertising and Book Arts, and Technical Drawing at the National School of Fine Arts and at the School of Philosophy, graduating in Drawing in 1957.3 The following year, she received the annual scholarship from the "United States Government Program for Technical Cooperation with Other Governments", to specialize in Secondary Education at Southern University, California, and at the New Mexico Highlands University, in New Mexico.

However, the highlight of her stay in the United States was the internship that Celeida Tostes did with the Navajo Indian María Martínez (1887-1981), an encounter that would definitely change her artistic career. Known as "the Potter of San Ildefonso," Martínez was an international reference of Native American ceramics. A descendant of the Tewa people of the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, she rescued the ancestral black ceramic technique of her people, based on the observation of pieces from the 17th century and through a tenacious research of materials.4 With María Martínez, the Carioca artist learned the "handling of clay, the adobe mixture and indigenous ceramics and, according to Celeida herself, the coexistence was decisive in choosing clay as the raw material for her work."5 During this North American season, Celeida also got to know the ceramic work of the Comanche and Apache peoples.

Upon returning to Brazil in 1959, the artist was already in a transition of interests, gradually abandoning printmaking and embracing the technique of enameling on metal. Unlike engraving, ceramics was not present in the Brazilian avant-garde experimentations, except for the use of ceramic panels that adorned modern architecture; some pieces in clay made by Bruno Giorgi and Ernesto de Fiore, and others in terracotta by Victor Brecheret,6 during the years 1940/1950. This support was only associated with the productions of popular artists from Vale do Jequitinhonha and the Northeast, such as Mestre Vitalino,7 and indigenous statuary, in addition to decorative and applied arts. Francisco Brennand, an artist of the same generation as Celeida, who gained national recognitionwith large ceramic sculptures, would only begin his systematic production of sculptures in the mid-1960s.8

Therefore, Celeida Tostes began a solitary linguistic exploration among her peers of the Brazilian neo avant-garde and found, in the field of education, a space where she could sediment her knowledge and the expansion of techniques related to ceramics, whose dynamics she taught while learning. There is no indication that there was an ideological or political direction for this choice, but only the convergence of a newly acquired interest and knowledge, added to the work opportunities that arose upon her return to the country. This path began in 1960, with the project "Complementary Teaching Plan in Brazil," led by educator Anísio Teixeira. It was a program of the National Institute of Pedagogical Studies of the Ministry of Education, which sought to bring back to school children who had abandoned their studies after the first cycle of education; to restructure schools and to requalify teachers of the public education network throughout the country, who went to Rio de Janeiro as scholarship holders.

In 1960, the artist began to teach enameling on metal at the Industrial Arts Course of INEP/MEC, making use of alternative materials with the educators, as a source of income option for her students, who were children from the lower social classes, to get out of situations of vulnerability and criminality. Thus, there was an intervention of art in the social reality. In the process of the course, Celeida noticed people's lack of familiarity with the use of their senses in the observation of their daily life. This experience was fundamental for the construction of her pedagogy, which was based on the "recovery of the importance of the tactile exercise, the awareness of one's own body as form, inside and out, and the contact with the skin, touch, the relationship from inside the body with the outside world through the skin."10

With the civic-military coup that was installed in Brazil in 1964, the projects that sought to incorporate more progressive measures in the field of education were extinguished, such as Anísio Teixeira's program. Despite the closure, Celeida Tostes continued her apprenticeship, the construction of her method, and her work in public art education as a contracted teacher for the Rio de Janeiro State Education Network, working in early childhood education and teacher training. In analyzing her curriculum, one notices the absence of exhibitions between 1959 and 1979, a period in which great artistic changes took place all over the world, and which in Brazil meant an experimental leap towards contemporary art in the midst of the military dictatorship. For Celeida Tostes, this revolution took place in the blurring of boundaries between art and education, as well as in the creation of collective works instead of individual ones. In 1973, she entered the postgraduate course in Cultural Anthropology at the Faculty of Education of the UFRJ and, in 1975, with a scholarship from the British Council, she spent a month at the Cardiff College of Art, in Wales, United Kingdom, further deepening her knowledge of ceramics.

Celeida Tostes' pedagogy actually began to take shape from the Como Somos project, developed at the Niterói Educational Center11 of the Brazilian Education Foundation, between 1972 and 1975. This was a proposal with students, which sought to sharpen the awareness of one's own body through touch, activating the relationship between the inner world and the outer world through the skin and the act of touching. In a classroom exercise, for example, the artist and her students created glazes from tree leaves and grass, which were associated with other materials in an intermediate process of empiricism and intuition, of observation and experimentation.12 The exercises with lines, shapes, structures, movement, and space that occupied the students, led them to access personal references and to get in touch with their own sensibility and personal reference:

«From the first activities with the children in the schools, I saw how they were unaware of very close and simple things. Feeling the water, observing the ground, the trees or their bodies. They were boys and girls from various socioeconomic strata, from Penha, Mangueira, Botafogo, and Vila Izabel; some teenagers, others seven and ten years old. It was as if there was little use of the senses. Few would be able to tell some details about their skin, their hand or the classroom itself. Again, the 'distance' of what is near. It was the lack of exercise of the possibilities of using.»

13

Activating the senses (mostly touch), exploring materials empirically and intuitively, connecting with their subjectivity and context. The experience of Como Somos, at the Niterói Educational Center, shaped Celeida's methodology. According to her,14 this experience shaped her later proposals already established in artistic institutions such as the Fire Arts and Material Transformation Workshop, the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts (between 1975 and 1989), and was a reference for the Integrated Ceramics Workshop Project - School of Arts/Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, in 1989.

The Parque Lage School of Visual Arts (EAV-Parque Lage), created in 1975 in Rio de Janeiro, was Celeida Tostes' great laboratory, and the opportunity for the expansion and visibility of her pedagogy. The aim of the School—developed by the artist Rubens Gerchman (who directed it between 1975 and 1979), one of the most relevant names of the Brazilian neo-avant-gardes—was to become an open and interdisciplinary structure that would propitiate the expansion of the limits of creation and artistic thought. The invitation to Celeida Tostes arose from the recognition of the artist's excellence and the potential she would bring to the institution: "Celeida was very prepared, she had just returned from England. The invitation allowed her to emerge from the ostracism in which she was living as a state secondary school teacher. At the EAV she was able to fully develop her capacity and sensitivity. It was a very difficult time, under the military dictatorship."16

If from the outside the military repression limited freedom of expression and questioning, seeking to frame people in a technical education, inside, at the Fire Arts Workshop, the rule was to decondition students and "not" to provide them with techniques, formulas, and aesthetic rules. On the contrary, Celeida Tostes was concerned with intuitive discovery and the empirical process of constructing personal and organic languages. In her classes, the dialogue with clay was stimulated on three levels: affective, cognitive and motor. The central issue was the transformation of both materials and people. In this process, not only the clay went into the kiln but also the students; that is, the classes focused on the production of objects, as well as on the discovery and maturity of their subjectivities.17 The excerpts from the text written by Mario Margutti for Revista GAM about an afternoon of activity in the course, describe the methodological dynamics as follows:

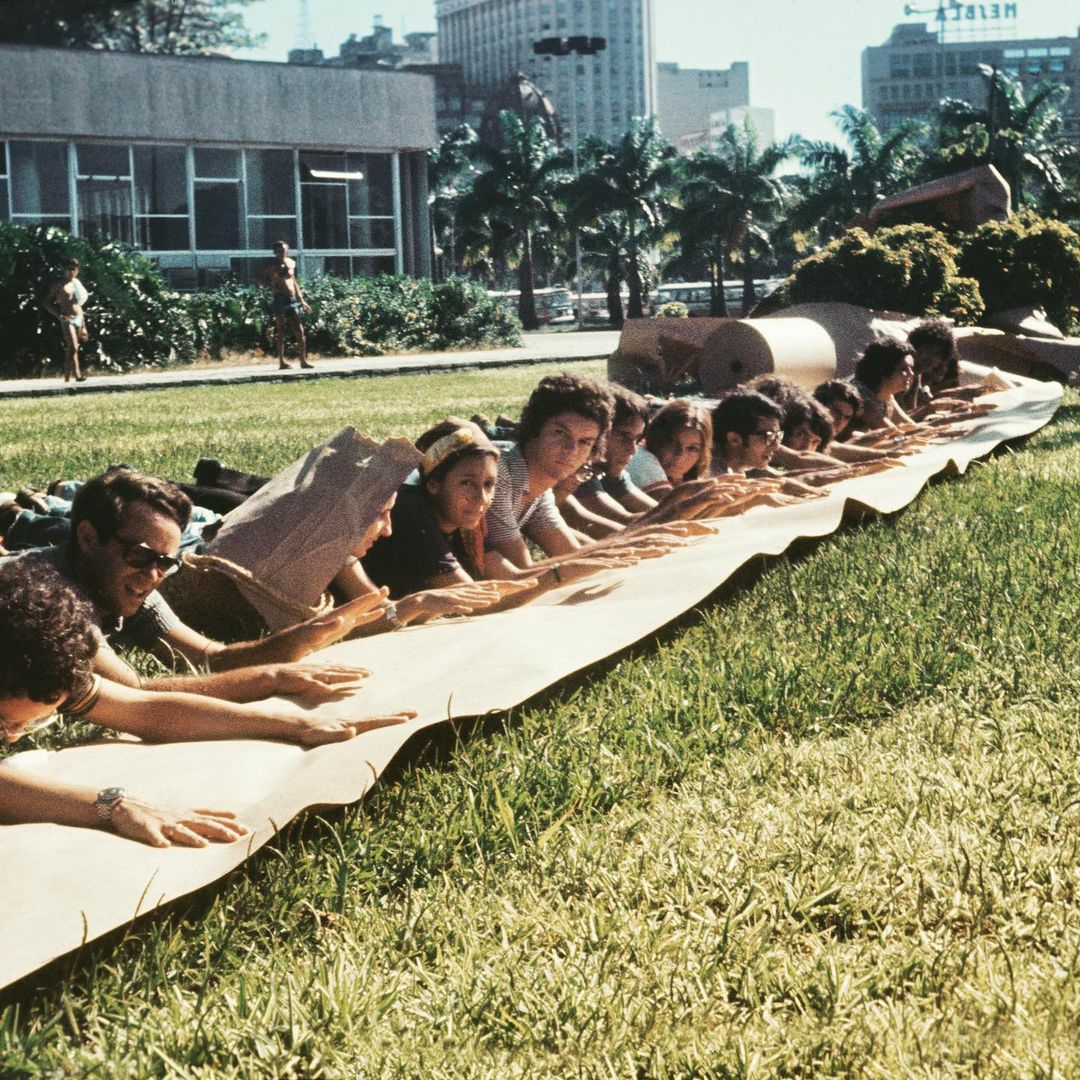

«A sensitization ritual in the open air, followed by a spontaneous collective creation, to finally study empirically the transformation of some materials by the action of fire. This was the first practical work carried out in 1976 by the students of the Fire Arts course at the EAV, under the supervision of Celeida Tostes. It all began with the exploration of sensory relationships with the 4 elements of nature (fire, earth, water and air), separately and together. Then came the collective creation with clay, candles, colors, shapes. At the end, a circle of people around the fire, covered with crucibles and 'tongs,' observing the effects of heat on random mixtures of clay, salt, borax, tetraborate, and sodium carbonate.»

One of the students in the course described the first part of the experience, "We sat down and tried to feel the air inside and outside the body, the inhalation and exhalation, the absence of air, its excess in the wind. Then we lit candles and watched the air in the flame, the air from us in the fire, played with the candles in our hands, watched the fire extinguish or increase. At each step, between one stage and another (change of elements), we made a stop to become aware. Then came the buckets of water, the cold, the blowing in the water, the washing of the faces, the spontaneous passing of the water through the earth, wetting the ground. The soil was there and, once mixed with the water, it is good to remove it. Then the group created a kind of sculpture, a 'crowned head' full of tentacles on all sides, a 'spider' that we immediately began to color."18

Despite her intense participation in the life of the EAV, the expansive character of Celeida's artistic-pedagogical practice took her beyond the walls of Parque Lage, that is, beyond the artistic milieu of Rio de Janeiro's middle class. In 1978, together with students and teachers from the Escola Guignard, in Minas Gerais, she led the project "Utility Ceramics with Professionalization," which sought to provide technical training to women deprived of their liberty. The following year, the artist headed the proposal "Tile Factory and Recovery of Cultural Memory" in São Luiz - Maranhão. Promoted by the Integral Development Program for Artistic Education of the Ministry of Education and Culture, the project sought to restore the tile facades of old houses with the labor of low-income children and adolescents, who knew how to make tiles.19

In the same period, the Morro do Chapéu Mangueira, south of Rio de Janeiro, entered Celeida Tostes' life. This encounter would lead to the project "Formation of Utility Ceramics Centers in Communities of the Urban Periphery - called favelas" (1980-1994), another milestone in her biography. The initiative consisted of a fruitful partnership with local residents, in which students from the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts, artist Anna Carolina, and historian Carmem Vargas also participated. The process, which lasted five years, involved listening to the life stories of the inhabitants of the hill, mostly made up of migrants from the Northeast; the study and removal of the clay found on the site; the construction of a kiln to burn the pieces, and the organization of exhibitions and sales at fairs. There were three main purposes: the expression of the memory of the participants, the professionalization of the artists, and the generation of income.20

In Vargas' words:

«The project was not to make a pretty basket, the same kitchen towels for everyone. No... each one created their work based on what they already did, on their ancestral memories. The memories led to the construction of works that were already made at the origin [in the participants' place of origin]. The dollmaker made dolls in the municipality where she lived. This memory migrated and was reconstituted when it was recovered through art, not only in memory, in abstraction. The dollmaker reconstructed her memory in the artwork that was the doll made in Morro Chapéu Mangueira.»

21

Despite the social differences among the students, the basis of the pedagogy applied in the initiative was similar to the work developed in the EAV. This is what is some of Celeida’s statements indicate, for example, "The guiding concern [of the project] is not the transmission of techniques of making, but the discovery through making, aiming at the awareness of the already existing resources [...], the relationship of this with the raw material and, within this process, provoke the generation and rescue of the creative language."22 Some exhibitions emerged from this process, such as Argila, um universo23 [Clay, a universe], curated by Celeida Tostes, at the Federal Economic Fund Gallery, in Rio de Janeiro, in 1987.

Without raising ideological flags, the pedagogy that Celeida was building throughout the sixties and seventies, prioritized the democratization of expression through the art of other social strata and groups of different ages. It was based on horizontal encounters between educator-student and student-educator, in a constant dialogue full of rigor, affection, and respect. She did not seek to inculcate aesthetic standards in the students, but to help each one find their own language in a process of self-reflection and experimentation with clay; she sought to generate an integration of knowledge. Her artistic practice began to develop more systematically from the end of the 1970s onwards, and these principles were reflected especially in terms of the collective and non-hierarchical aspects, both in the production of the works and in their exhibition. We could cite as examples O Muro (1982) and Passagem (1979), the artist's most celebrated work, presented in her first solo show with clay works, at the Rodrigo Mello Franco de Andrade Gallery, in Funarte. The exhibition was developed in dialogue with the solo exhibition of her student Nelly Gutmacher at the same space. The emancipatory, dialogic, and experimental character of Celeida Tostes' pedagogy and its intertwining with her artistic practice remains one of the most radical examples of art education in Brazil.

Celeida Tostes collaborated with innovative public projects of emancipatory education articulated outside art schools. Tostes served as a teacher of enameling on metals in the Industrial Arts Course of Anísio Teixeira's Plan for Complementary Education in Brazil, whose focus was to update teachers' knowledge and to renovate the physical structures of public schools. The purpose of the classes taught by Celeida was to train teachers with techniques that would be passed on to students as an option for earning income.

From the documents that have come down to us, we can assume that Celeida presents a singular way of inventing artistic communities and propitiating the students' encounter with their reality and expressiveness. Her pedagogy was structured on the basis of her individual trajectory and perception, aiming at the expressive development of students. Her method sought a connection between the students and the elements of nature, bodily sensations, and associations with their ancestry, which was consistent with their chosen material: clay. In Celeida's artistic-pedagogical practice, the popular resided in the de-hierarchization of the subject to which she dedicated her life, and which even today is associated with the most invisible social strata, as well as the attempt to intertwine students with very different backgrounds. In her art teaching methodology, the core does not lie in imposing models but in betting on the process and experimentation.

Art is a device for social change and the production of artworks was not the main focus, since for Celeida Tostes, making art was beyond individual performance and the making of objects. Her legacy points to hybrid, organic, transformative, and emancipatory ways of interrelating art, education, and life. Her practice unravels concepts, challenges the dynamics of the art world, and transposes the thinking of the fundamental educators of the 20th century to art education.