La Escuela___: You have stated that you didn't know who Lygia Pape was when you established a close working and friendship relationship with her. But when did you realize that you were in front of a key artist for the development of Latin American contemporary art? How did you make the transition from rejection to affection?

Experience an Instant with Reality

08/14/2022

with Ronald Duarte

Lygia Pape (Nova Friburgo, Brasil, 1927 – Río de Janeiro, Brasil, 2004) was a key multidisciplinary artist in the development of contemporary expressions in Brazil and Latin America. With a special interest in the spatial phenomena derived from interaction between the work and public participation, Pape developed a pedagogical experience in which the experimentalism of her radical approaches defined the interests and direction of many of her students.

Among these, we find Ronald Duarte (Barra Mansa, Brazil, 1963), artist and curator, whose micro-political strategies take over public space through interventions filled with poetry and symbolism. From Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Duarte talks with La Escuela___ in order to help us understand the experiences shared with his great teacher.

Ronald Duarte: For me there was never a transition since affection always existed. I never thought we could get along just because I realized I was next to an iconic person in art. I never thought Lygia Pape would solve my problems; mine were mine and hers were hers, we simply exchanged them. We understood each other and that was what united our friendship, our affection and our trust. Our friendship merged without cuteness, in the non-exaltation of the artist. Artista é o caralho, as Rubinho Jacobina used to say.

"Art cannot be taught" is one of the most radical and recurrent statements Lygia made when speaking on the subject of art and education. However, she was an outstanding pedagogue in both art and architecture schools. How was Lygia Pape, the teacher?

What Lygia said is not contradictory at all. Art is not really taught and she is right (and I agree in gender, number and degree). I think the question is a provocation, a prick, an awakening in the person: who is she? Where is she in front of the mirror? Waking up, observing your foot, observing.... Where do you really stand? Who are you? Where are you going? (How to take decisions?!). These questions continue to be the same for everyone, Lygia only placed a magnifying glass on this search, on this anxiety of search that the artist has and that leaves us restless. She spoke to the restless, to those who were searching. She wanted potent, lively people.

So she sharpened that vivacity, her pedagogy was as vital as a snake. "Either you rise or you fall," either you die from the poison or you live for it. She proposed to live on poison, but "on the razor's edge," in a limit in which she "stretched the elastic," she really stretched the elastic!—both in relationships and in friendships.

Do you remember her classroom dynamics?

One dynamic she used a lot was surprise. The exercises in the classroom were not common they were based on choice. For example, Lygia would ask us to leave the room and look for something we didn't knew; from that experience we had to create a work, look for an abyss, the unexplored, what we didn't realize we were looking for. What you found became the purpose of the work.

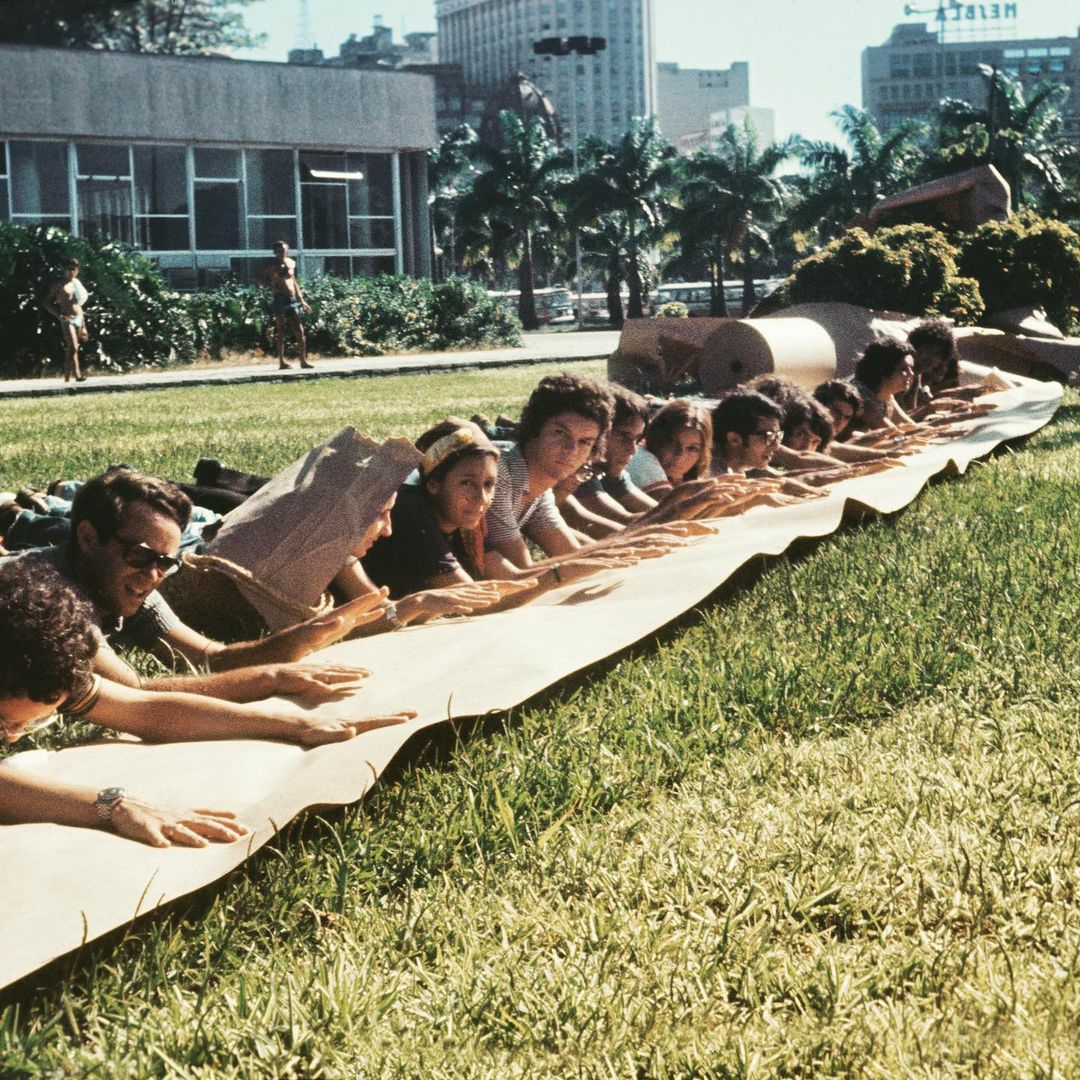

In different bodies of work—such as Divisor [Divider] (1968)—Lygia Pape determines an important place for the viewer/activator regarding free will of action, but when teaching, how important was freedom in class and in her methodologies?

The important thing in Divisor was that even if it seized your head you had freedom. Even though Divisor cuts off the body from the head, that is, the thought of the organicity of the body—of the mule without a head, of the headless body—this division makes you think about how my head thinks, how my body reacts. So to participate in Divisor was to carry a lost head in the midst of so many headless bodies, in the midst of so many sensations—an experience like no other.

Divisor has this particularity of dividing the mental: the irrational from the rational, the possible from the impossible. Lygia told an anecdote about these two dichotomous worlds that society itself created: she develops a collective body without a head. An emblematic and marvelous work. No one will ever do anything like it.

You also said that Pape taught you to be "institutionally political," in relation to her ability to administer and manage artistic and research projects. How did Lygia articulate her (unconventional) pedagogical experience within the traditional structure of a university?

Lygia made the impossible possible and achieved things that no one else could. She was short, always dressed in black and walking with her nose upwards, looking straight ahead at the sky in the corridor of the School of Fine Arts (UFRJ), as if she were carrying a force. For the institutions, Lygia "advanced" because she was politically correct, she did what she had to do: she sent the report, the notes, she kept the schedule and nobody stopped her in the hallway. She was a very serious person.

Her methodology was her own. She used her right as a teacher in the classroom, where the teacher is in charge, in order for the institution not to intervene. The classroom was her territory: she knew how to evaluate, how to challenge, how to speak. The institution did not interfere in her methodology. That is why radicality was part of her way of proceeding.

Hélio Oiticica was a very important person for Lygia Pape; she even took on the responsibility of disseminating and showing his legacy after Oiticica passed away. What do you know about this bond? How did Hélio's thinking influence Lygia (or vice versa)?

This is a very good question. They were really thick as thieves, they were very close friends, and she loved him. She felt sorry for his death, she was even the one who found him dead so early.... But he couldn't bear himself, for everything: for the moment he was living, for the acceptance or not of the market itself, for all the new things he had been presenting and that were only seen later. But the one who knew this was Lygia, she was his accomplice, the one who knew everything he thought.

Even with the criticisms of many people, Hélio was a genius—his legacy is eternal. For me he truly is the first Brazilian postmodern artist who even leaves the dialogue of the academy and goes towards the body, towards space; this extension of Hélio's work—currently in force—will remain for much longer, the legacy is gigantic. Today we know the universal breadth that was Hélio's legacy, but at that time Lygia made a great effort to make it happen.

Together with Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape dedicated herself to the study of the areas of urban exclusion in Brazil, of the proletariat, the exploited, popular culture, and that which wasn’t easily seen in the art of modern Brazil. Pape's geometries seem to immerse themselves in these excluded and marginal areas and extract from them the "impure" nature of their movements, their gestures and their forms. In previous occasions you commented, "Lygia Pape was the people," do you think that contemporary Brazilian artists have a relationship with the reality of their context as Pape did in the sixties?

It's funny this ‘impure nature’ thing because to me nature is super pure. In fact, it is purer precisely because it has not yet been captured, it is not catalogued and it is very organic. For example, Espaços Imantados is a wonderful work by Lygia, which also has a lot to do with Hélio Oiticica's Nas Quebradas. The quebradas are corners of Morro do Caminho, where the hill descends and almost falls. The spaços imantados are public spaces of spontaneous agglomerations that happen in urban spaces. For example, here in Rio de Janeiro they can be observed in Largo da Carioca, with a person doing magic or gambling to which everyone joins. Lygia takes these popular, peripheral movements as a magnet that attracts everyone to the same place; Hélio takes the quebradas, which are also a popular, peripheral space, as well as a way out, a path, and a shortcut. So there is this relationship of strength and truth from the periphery. Nobody was making "grimaces" or "painting their lips" to look different, they were there reinventing themselves. It is about these forces, about these people, about them trying to live; it is in them that Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica are interested, because that is where life is.

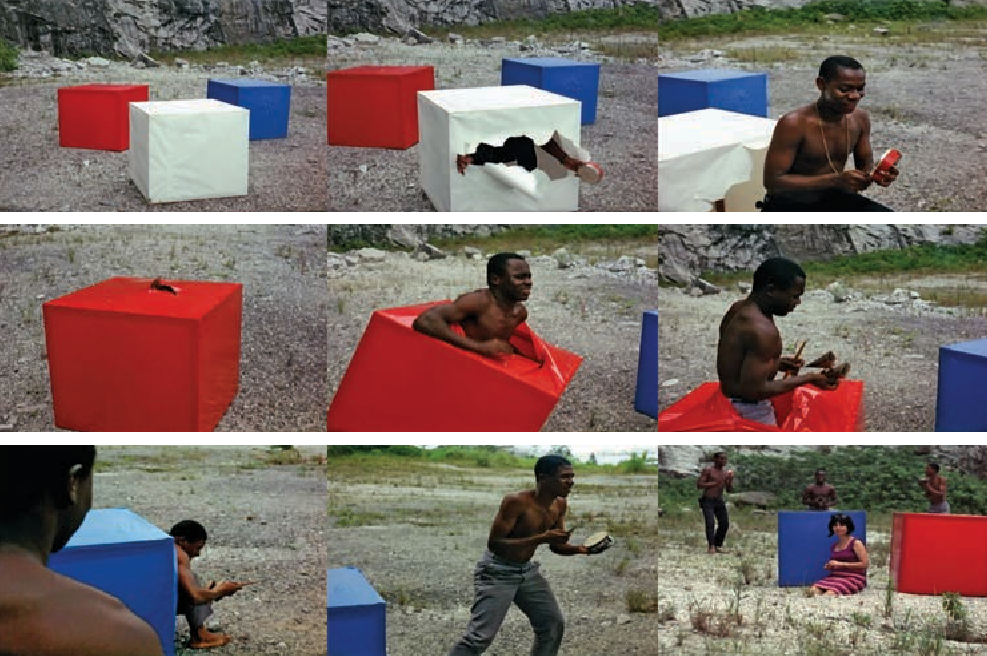

Lygia was a precursor of this. She even paid attention to this social issue at a time when no one else was noticing it. Today, television and the film media appropriate the image of the Black man to commercialize it, which seems to me to be nonsense, because racism is structural and rooted, it all comes from colonization and society has not ceased to be racist. When Lygia values people, she values the peripheral, she goes for those who are on the margins. There is Hélio's phrase: "Seja marginal, seja herói" [Be marginal, be a hero]. Both Lygia and Hélio are showing the true viscerality of life and not its appearance.

In Pape's work there is no conflict between the modern purity of art and its politicization, that is to say: her geometric forms coexist with their political implications and meanings. In her work as an artist, the critique frees itself from any formal inheritance to speak of resources that directly allude to the social and political crises of the Brazilian context; however, collectivity remains a common concept. How do you understand the concept of 'multitude' and how is it integrated in her work?

A phrase by Lygia Pape: "Nothing separates erudite art from popular art"; this phrase explains everything. Due to the overvaluation of erudite art, of the so-called "great" art, popular and street art are seen as "craftsmanship", but Lygia saw them both as art. So, this power of the people, of the multitude that presents itself, had the same weight as a work by Puccini.

Lygia taught me to value my roots within my work. I come from the periphery, from a lower class in the interior of Rio de Janeiro; the multitude is part of my life, as a force, a power and a base. I never belonged to a traditional, patriarchal, numerical, surname family. We were people of the people; we were part of the people and the multitude. Lygia always knew it. She showed the strength of the people to the people. To be a multitude, to be body to body and to be aware of your place in society as a whole, is to structure micro-politics with your peers, to be able to find the other and to recognize yourself in the other—to notice the plurality of your power and the reverberation of this as a whole. All this has a relationship with indigenous, humanitarian issues.

The public space is an important place for activation and interaction with your works. How do you think group artistic manifestations—collective, participatory—can be affected in an era like the present, in which distances and approaches between individuals have been reconfigured?

It's true, it's very difficult and I've thought about it. "It is necessary to be attentive and strong. We don't have time to death," is an emblematic phrase [from the song Divino maravilhoso by Gal Costa]. It is the work I am doing with the Boiada de Ouro [Golden Flock], which is being done in single line, with detachment and applauding death itself. The flock is aware of its own death—we are all, happily or unhappily, going to die—so it has been very difficult. But how do I plan to organize this collective according to the WHO protocols? Although I think it's possible, the affection, the need for hugs, for touching each other, is still powerful and leaps eagerly to happen; but I think consciousness is also about re-educating, re-dimensioning and placing oneself in space.

In works of your authorship, such as Mar de Amor (2013), you make a call to rescue and respect human relationships of affection, in parallel with a denunciation of violence. How did the public perceive this message, both political and poetic? How do you understand the relationship between these two words, 'political' and 'poetic'?

It's coded. The public didn't notice everything about that work. I think until today it hasn't been understood. The context around it is the assassination of Amarildo [de Souza] by a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in the south zone;1 they disappeared with the boy's body, who was handed over as a criminal, but they had no right to take his life. They spoke in a way as if they had just killed a pig, and not even to kill a pig such violence was necessary. It was then that I realized that Rio de Janeiro was a sea of blood.

In other words, all my works—both Mar de Amor and O que rola você vê [What happens you see]—are about clear action, and I think this is a counterpoint to the real thing. Politically and affectionately, it is clear that there is no room for "not being what one is." When I speak of a "sea of love," contrasting the violence we live, it becomes evident, because there is no room for innocence, only blows in the face, that's what we experience! Politically and poetically it is very clear.

Your actions in public space are radical, they act "where the wounds of the city scream." What are these wounds in Brazil today? Do you think art can heal them?

These questions are huge: wounds in Brazil? God, there are so many wounds in Brazil! So much cowardice, what they have done to the indigenous peoples for more than 500 years, this is the biggest wound. I really hope that Lygia Pape, with her Tupinambá mantle, can show the world the size of the wound, which is the mortality of the indigenous people. How to heal it? That is the greatest struggle of all struggles. Does art have the power to heal the wounds? I don't know what the limit is, but I believe in the power of art although it is terrible to imagine all this.

In terms of art and its capacity to be a social transformer, micropolitics have replaced the great utopias. In your case, as an artist, manager and curator, you put a lot of emphasis on this term, why?

Yes, I place a lot of emphasis and I will continue to do so because micropolitics are a reality. There is nothing utopian: I am here body to body embracing; I am here body to body, making the herd that the government wants to take. But this herd is conscious, it knows that it is ox and that it is people, this herd sustains the country that is the machine. Of course, I emphasize that micro-politics are the only weapons I have access to, and I give my arm and the extension of it, where I can put my hand and see face to face.

What lessons from Pape do you keep with you today?

The biggest lesson Lygia gave me for doing anything with intention and choice is to not preconceptualize; that is, to experience an instant with your truth, reality and sensibility. The word 'truth' is dangerous, but your "being sensitive" is believing in your inner self, knowing who you are, feeling the other. If you know what you are feeling, you can externalize it, without making it up or doing it without a filter. I think Lygia Pape taught me to see myself and to be as I am. To be raw, to have distance to observe and even see what you are feeling—if it's hurting, to feel the pain without pretending it doesn't exist.